Le Bois Sec Refleuri

Guide pour rendre propice l'étoile qui garde chaque homme

Traduits par Hong-Tjyong-Ou etc.

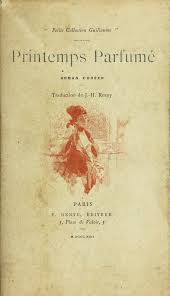

In 1892, a French translation of the Tale of Chun-Hyang was published as Printemps Parfumé under the name of J.-H. Rosny (link to complete French text) (Link to English translation)

The complete French text of Le Bois Sec Refleuri, published in 1895 with Hong-Tjyong-ou as sole author / translator, is linked to below, divided into its chapters.

Le Bois Sec Refleuri was translated into English by Charles M. Taylor, and published in 1919 with the title Winning Buddha's Smile (link to complete English text).

The translation of Guide pour rendre propice l'étoile qui garde chaque homme et pour connaitre les destinées de l'année was begun by Hong then completed by Henri Chevalier after his departure. (1) link to PDF file (2) link to the online text in the Internet Archive reader

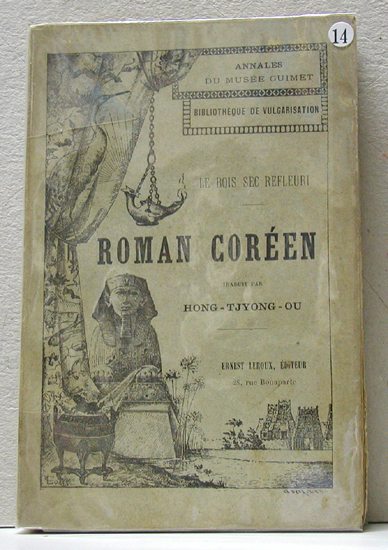

Photo in the Musée Guimet |

Photo donated to the BNF by Henri Chevalier |

|

|

In addition to a link to biographical information about Hong Jong-u, this page offers links to the three French publications of classical Korean works which he helped translate.

The first of the three, Printemps Parfumé, a version of the Tale of Chunhyang, issued in 1892, was published under the name of J.-H. Rosny. J.-H. Rosny was the pseudonym of the brothers Joseph Henri Honoré Boex (1856–1940) and Séraphin Justin François Boex (1859–1948), both born in Brussels. They were active in France, founding members of the Académie Goncourt in 1903 and its presidents late in their lives It seems that Printemps Parfumé was in fact the work of Séraphin since La Convention littéraire de 1935 designed to distinguish between their works attributes it to "J.-H. Rosny jeune." An article on Hong-Tjyong-Ou, signed J.-H. Rosny, in Le Carillon du boulevard Brune n°11 (1894) refers to "Hong-Tjyong-Ou, le traducteur – en collaboration avec nous – de Printemps parfumé." In 1911, J.-H. Rosny jeune published a tale titled "Une Légende Coréenne" in a volume of short tales, in which he seems to evoke memories of evenings spent with Hong Jong-u. The legend is inspired by that of the Emile Bell in Gyeongju.

Hong had already left France before the Musée Guimet published Le bois sec refleuri under his name in 1895. Le Bois Sec Refleuri, the second Korean tale 'translated' into French with the help of or by Hong Jong-U, is essentially the tale usually known as Shim Cheong but it is very unlike the version known in Korea today, in the Pansori or the older novel.

In 1897, the museum also published in its Annales, Guide pour rendre propice l'étoile qui garde chaque homme et pour connaitre les destinées de l'année (Jikseong haengnyeong pyeonram 직성행녕편람) with Hong's name and that of Henri Chevalier as joint authors. In the Introduction, Chevalier indicates that the original book was one of those brought back by Charles Varat, that Emile Guimet had selected it for translation, that Hong left to return home not long after the work began, and that he had been helped in completing the translation by W. G. Aston, the former British Consul-General in Seoul.

The Life of Hong Jong-u (on a separate page)

French texts about or inspired by Hong:

An informative article about Hong, written by the French artist Félix Régamey (1844 – 1907), was published in Volume 5 of the review T'oung Pao in 1894, soon after the arrival in France of news of the killing by him of the Korean reformer Kim Ok-gyun. Other articles followed. The short article signed J.-H. Rosny from Le Carillon du Boulevard Brune, 1st year, number 11, May 1894 indicates how perturbed Hong's French friends were on hearing what he had done. Some time later, in another essay, Rosny offered a more nuanced and more detailed portrait of Hong and his inner world.

An article in Le Figaro of March 6, 1891 announcing Hong's arrival in Paris and inviting people to help him (also in English) in a rather mocking tone

An article in Le Figaro of May 19, 1894 announcing the killing of Kim Ok-Gyun by Hong Jong-U and recalling his time in Paris in a hostile tone (also in English)

An article about Hong's time in France, written by the artist Félix Régamey (1844 – 1907), in Volume 5 of the review T'oung Pao in 1894

An article signed J.-H. Rosny about Korean customs, based on conversations with Hong Jong-u from La Revue Bleue Tome LII No. 2 le 8 juillet 1893 pages 47 - 52

An article on Hong-Jong-u signed J.-H. Rosny, in Le Carillon du boulevard Brune n°11 (1894)

An essay about Hong by George Clemenceau. (Clemenceau was close to the Rosny brothers)

An article about Hong by Ernest Tissot (based on Rosny's articles)

An article about Korea mentioning Hong signed Alexandra Myrial (Alexandra David-Néel)

An essay by J.-H. Rosny jeune, relating a Korean legend (Emile Bell) with a description of Hong.

An extended article (translated into English) about the origins of the Sino-Japanese War by Édouard Chavannes from: La Revue de Paris, (15 August, 1894, pages 753-768) "La guerre de Corée"

Annales du Musée Guimet

Bibliothèque de vulgarisation

Le Bois sec refleuri

Traduit par Hong-Tjyong-Ou

E. Leroux (Paris) 1895

Text of the copy in the BNF received via their Gallica service

En raison de l'intérêt qu'il présente comme spécimen de la littérature, encore si peu connue de la Corée, l'Administration du Musée Guimet a pensé pouvoir exceptionnellement publier dans sa Bibliothèque de Vulgarisation le roman intitulé « Le Bois sec refleuri », qui passe pour l'une des compositions littéraires les plus anciennes et les plus estimées de ce pays. L'auteur de cette traduction, M. Hong-Tjyong-Ou, qui fut attaché pendant deux ans au Musée Guimet, s'est appliqué à en rendre scrupuleusement, presque mot à mot, le style et la naïveté, et les éditeurs n'ont eu garde de corriger son oeuvre afin de lui laisser toute sa saveur exotique et primitive.

DEDICACE

MON CHER AMI HYACINTE LOYSON,

Bien des fois dans la maison que votre amitié sait rendre si hospitalière, nous avons discuté tous les deux les insondables problèmes de nos origines et de nos destinées. Les milieux si différents dans lesquels nous sommes nés et avons vécu ont modelé nos esprits et leur ont imprimé un cachet bien différent aussi. Peut-être, si l'on pouvait juger les choses de plus haut que la terre, seriez-vous trouvé trop Catholique et moi trop Païen. Vous, ne voyant rien de plus élevé, ni même d'égal au Christianisme; moi ne comprenant rien à vos dogmes étranges, tandis que je trouve en Confucius plus de sagesse qu'en toutes vos lois et que Lao-Tseu planant dans une sagesse presque surhumaine fait monter ma pensée plus haut que les choses entrevues et les choses rêvées, pour la plonger dans l'Infini.

Mais qu'importe ! Je crois qu'un seul Dieu nous a donné la vie. Ce n'est pas un être étrange habitant loin, bien loin dans la profondeur des espaces éthérés un palais fantastique bâti par-delà les étoiles. C'est l'Ame de nos âmes, la Vie de nos vies, notre vrai Père, Celui en qui et par qui nous sommes tous. Tous nous sommes frères, car tous nous sommes issus de Lui ; mais combien nous nous sentons plus unis et plus frères, nous qui croyons tous deux en lui, bien que notre foi s'exprime de façons différentes.

J'ai fait un long voyage, passant comme en un rêve au milieu de toutes choses. Depuis que j'ai quitté ma patrie, j'ai marché à travers la brume grise toujours cherchant ce que mon esprit pressentait, sans le trouver jamais ; quand soudain, comme l'éclair brillant qui déchire les sombres nuées d'orage, la lecture de votre testament m'éveilla; car votre pensée me montra comme en un miroir ma propre idée poursuivie depuis si longtemps. Puissiez-vous transmettre à votre fils l'enthousiasme qui vous anime ! Qu'il s'inspire de votre pensée et poursuive l'oeuvre que vous avez si vaillamment entreprise !

Hélas ! encore quelques jours et nous serons séparés car je m'en vais loin, bien loin par-delà les mers ; mais de retour dans mon pays je garderai toujours fidèlement le souvenir de votre amitié.

Quand vous verrez dans le ciel passer de blancs nuages venant d'Orient, songez à l'ami fidèle qui songe à vous, là-bas sur la rive lointaine et qui parle de vous à tous les nuages et à tous les oiseaux allant vers l'Occident afin que quelques-uns d'entre eux, dociles à sa voix, viennent raviver en votre coeur le souvenir de son amitié.

HONG-TJYONG-OU

Neuilly près Paris, le 15 juillet 1893.

CHER ET RESPECTABLE LETTRÉ.

J'accepte avec reconnaissance la dédicace que vous voulez bien me faire de votre prochain ouvrage. Je n'en connais encore que le titre, mais il est bien choisi. En Occident comme en Orient, l'humanité est ce « Bois sec qui refleurira ! »

Je suis Chrétien et veux demeurer tel. Je crois que la Parole et la Raison suprême, Tao, comme l'appelle votre philosophe Lao-Tseu. s'est manifestée sur cette terre en Jésus-Christ ; mais je crois aussi que les Chrétiens ont été le plus souvent bien indignes de leur Maître.

J'ajoute que dans le triste état où ils ont réduit la religion chrétienne les chrétiens sont capables de faire autant de mal que de bien, sinon plus encore, à ceux qu'ils appellent les païens et dont ils ne se doutent pas qu'ils auraient eux-mêmes beaucoup à apprendre.

Venez vous asseoir encore une fois à noire table de famille, mon cher ami païen, après quoi nous vous laisserons retourner dans votre chère Corée, en priant Dieu de vous conserver longtemps votre vieux père, votre femme et vos enfants, et en vous disant : Au revoir ici-bas ou ailleurs !

HYACINTHE LOYSON.

After these Dedications, the book begins with a Preface by the Author / Translator, dated January 15, 1893, offering a brief survey of the history of Korea. This indication of the notions of Korean history held by an ordinary, somewhat educated Korean at the end of the Joseon era would be of particular interest, if indeed it was written by Hong. Aston's review (see below) leads one to suspect that it was not (or else that he was really extremely ignorant and careless). The mention of Japanese spellings is especially significant.

This is followed by the novel itself, divided into 10 chapters.

Chapter One

The

wise and honest minister Sùn-Hyen, shocked on seeing

people lying in the street dead of hunger, scolds the

king for spending too much on feasts and pleasure. The

wicked, ambitious prime minister Ja-Jyo-Mi forges a

letter addressed to San-Houni, Sùn-Hyen’s closest

friend, apparently written by Sùn-Hyen, criticizing

the king harshly, and arranges for it to be found in

the street by the police. As a result, Sùn-Hyen and

his wife are sent into exile on the island Kang-Syn,

San-Houni and his wife are exiled to the island of

Ko-Koum-To.

Chapter Two

Sùn-Hyen and his wife arrive on the island Kang-Tjyen.

Until now childless, here the wife gives birth to a

daughter, named Tcheng-Y, and dies 3 days later.

Heartbroken, Sùn-Hyen sheds so many tears that he goes

blind. Nothing is said of the following years until

Tcheng-Y is 13 and begging food from neighbors.

Sùn-Hyen tells her what happened. She goes begging as

usual, is late coming home. Her father, anxious, goes

out looking for her and falls into a lake. He is

rescued by the pupil of a local hermit who tells him

that his sight and fortunes will be restored in 3

years (and will become prime minister) if he prays to

Tchen-Houang (Heavenly Emperor). If he gives him 300

sacks of rice he will pray in his place. He tells

Tcheng-Y about this, and she soon after agrees to sell

herself to merchants going across the sea to China who

need a young girl to sacrifice to obtain a safe

journey. They provide the rice at once. Three months

later, they come to fetch her and she has to tell her

father. The merchants are so touched by their grief

that they give another 100 sacks. After arranging for

her father to be cared for, she sets out with the

merchants.

Chapter Three

The scene shifts to San-Houni. Obliged to hire

transport to the island, he choose the 2 boatmen

brothers Sù-Roung and Sù-Yeng. Sù-Yeng is good and

Sù-Roung is wicked. Sù-Roung wants San-Houni’s wife

Tjeng-Si, so he has San-Houni murdered before her eyes

and entrusts Tjeng-Si to an old woman living nearby.

She too has seen her husband killed by Sù-Roung.

Sù-Yeng urges them to escape now, while his brother

(whom he hates) is drunk. They set off, then the old

woman takes Tjeng-Si’s shoes and sends her on ahead.

She places the shoes on the shore of a lake then

drowns herself. Tjeng-Si continues walking until she

suddenly gives birth to a boy. A nun finds her, agrees

to welcome her in the temple but not the baby, who

must be abandoned. Tjeng-Si tatooes the name San-Syeng

on the boy’s arm, hides a ring in his clothing, then

they leave the baby in the street of a nearby town.

Chapter Four

Sù-Roung wakes up, finds the women have left.

Following them, he finds the shoes and deduces that

Tjeng-Si has drowned herself. Then they head for the

nearby town and find the abandoned baby. Sù-Roung

adopts it and brings it up well. At school, other

pupils tell him that he is a foundling found by

Sù-Roung, who is not his father. San-Syeng finds his

name written on his arm and begins to wonder. He sets

out on a journey to

complete his education and reaches the town of

Tjen-Jou. There he sees a beautiful girl, whose father

has died and who lives with her mother, and they begin

an extended romantic courtship which leads to their

secret physical union. Finally the mother hears

something and orders a servant to kill whoever comes

out of her daughter’s room. The girls sees her father

in a dream who warns her, she tricks the servant and

San-Syeng escapes on her father’s horse with her

father’s sword. He gives her the ring.

Chapter Five

Wicked prime-minister Ja-Jyo-Mi wishes to be king.

When the king dies his son is still only a child.

After overcoming the enmity of the governors by fear,

Ja-Jyo-Mi sends the child-king into exile on the

island of Tchyo-To. San-Syeng hears of his misfortune,

wants to help. He dreams of a man who says he is from

his family, is called San-Houni, and was killed by

Sù-Roung. He encourages him to help the child-king but

refuses to tell him about his family. He sets out but

finds it impossible to land on Tchyo-To because of the

guards.

Chapter Six

Tcheng-Y jumps into the sea and finds herself on the

back of a giant turtle. They reach an island where it

deposits her in a dark tunnel. There she finds a

letter and 2 bottles of tonic, for her body and mind,

to give her strength to climb out through the roof,

where she finds herself inside a hollow tree in a

beautiful garden. It is the place of exile of the

boy-king. In despair, he is on his way to hang himself

when he sees a beautiful girl in the garden. He

decides to wait, they meet, he invites her to his

house, where he lives in isolation. They soon

celebrate a wedding ceremony and are united. Fearing

that he will soon be killed, they set fire to the

house and follow the tunnel back to the sea, where

Ki-si the young king is again in despair, there being

no boat in sight.

Chapter Seven

San-Houni again appears to San-Syeng in a dream and

tells him to take a boat to the island quickly. There

he finds Ki-si and his wife. He decides to wait to

confirm who they really are. Meanwhile the general in

charge of the prisoner on the island tells Ja-Jo-Mi

that he has died in the fire. He and his companions

are happy, the population at large is very angry with

them. San-Syeng takes the lead in preparing direct

opposition and finally is told by Tcheng-Y that Ki-si

is the young king, who is needed to justify the

revolt. The king is now treated with all the respect

due to his rank, the local authorities recognize him

and he starts to exercise authority, appointing

San-Syeng general. As they reach the capital there is

a general uprising, Ja-Jo-Mi is arrested. The king is

installed. He reduces the taxes and sends San-Syeng as

a secret inspector to check the quality of the local

governors.

Chapter Eight

The girl with whom San-Syeng had fallen in love, now

named as Tjyang-So-Tyjei, after the death of her

mother, loses everything in a popular uprising,

escapes and dresses as a man for safety. Lost and

exhausted, she falls asleep by the bamboo forest where

San-Syeng had been born years before. There she is

discovered by Tjyeng-Si, San-Syeng’s mother, who is

still living in the temple, and goes to the temple

with her. Tjyeng-Si recognizes the ring San-Syeng had

given to Tjyang-So-Tyjei and asks how she got it. The

identities are revealed. The two women set off, reach

the town of Saug-Tjyou, where the son of the innkeeper

falls for Tjyang-So-Tyjei. Rejected, he takes revenge

by having his own jewels hidden in their room then

claiming they had stolen them. Arrested, they are

taken before the magistrate who falls for

Tjyang-So-Tyjei and gives her the choice, marriage or

death. They are put in prison.

Chapter Nine

San-Syeng finds the house of Tjyang-So-Tyjei empty and

burned down. San-Houni appears in a dream, reveals his

identity as San-Syeng’s father and tells him what is

happening to Tjyang-So-Tyjei, Reaching the town,

San-Syeng has himself arrested and put in the prison

which is so dark they cannot see each other, though

the women wonder on hearing his name. The next morning

Tjyang-So-Tyjei sees the horse of her father outside

the window, exclamations lead to recognition. The

official identity of San-Syeng is proclaimed, the

magistrate is arrested, the women released from

prison. Mother and son, wife and husband are reunited.

He orders a monument for the woman who drowned herself

in the lake ; they visit the nun in the temple.

Sù-Roung is arrested and San-Syeng identifies himself,

and his mother who wants instant revenge for the

murder of her husband. Sù-Young, the good brother,

says that he will die if his brother dies. When they

tell the king and queen what has happened, the queen

Tcheng-Y is sad because she has not seen her father

for 3 years. The idea comes of a banquet for all the

blind men of the kingdom.

Chapter Ten

Blind Sùn-Hyen is told he has to go to the capital for

the banquet. When he arrives, the palace woman in

charge shows disgust at his dirtiness. He makes a very

eloquent, wise and poetic reply which is reported to

the queen. Then she has all the blind pass before her,

Sùn-Hyen is last, she recognizes him, asks if he knows

Tcheng-Y, and his eyes open. After hearing her tale,

he meets San-Syeng and learns that he is the son of

his old friend San-Houni. Sùn-Hyen is made

prime-minister. Finally, the king wishes to wage war

on the Tjin-Han who defeated his father once, and

there is still the question of the punishment for

Ja-Jo-Mi and Sù-Roung. Sùn-Hyen asks the king to hold

a great banquet for the whole population, saying that

they should support whatever is decided, war or peace,

punishment or forgiveness. He makes a speech in favor

of peace and reconciliation, all agree. Finally he

vanishes, perhaps taken up to heaven on a cloud.

This text of Le Bois sec refleuri derives from an OCR text file received from the National Library of France corrected by me (Brother Anthony). They ask that the source be indicated

The online text can be read here.

Some questions

A perceptive review of Le Bois sec Refleuri by the first British Consul-General in Seoul, the scholarly W. G. Aston, reproduced below, raises some important questions. The first question anyone must have on reading it is the nature of its source. Is this a direct adaptation / translation from a Korean original? Is there really an unknown Korean text in which the tale of Sim Cheong is radically changed and intermingled with a parallel tale? The second question regards the attribution of the text to Hong-Tjyong-Ou alone. Jo Jae-gon seems to suggest that Hong simply invented the tale as a sequel to Printemps Parfumé and raises no questions. I think most Koreans might not have good enough French to realize what a wonderful story Le Bois Sec is and how well written, not only as French but as narrative structure. It is a very professional production. It is to me unthinkable that Hong Jong-u simply produced it from nowhere. He could never have done it. Printemps Parfumé was written by "Rosny" not by Hong, for sure. Hong simply told the Boex brother the general outlines and had a Korean text from the Varat collection if he needed to refresh his memory. Perhaps, then, Le Bois Sec too was composed by one of the Boex brothers, but then after the murder he/they did not want the name "Rosny" associated with that of a dangerous criminal? Because the big question is whose work it really is, whether or not it is in some sense a translation. Not by Hong, certainly, judging from the really poor French he used in writing to Regamey only a few months after returning to Japan. It is also true that the end of the story reuses the Chunhyang tale (bad magistrate, woman in prison, love me or die, secret inspector, all ends well) so that might well point toward the "Rosny" brothers, who were expert writers of popular fiction and knew the Chunhyang tale. Hong might simply have summarized briefly the outline of the Sim Cheong story and they did the rest? The French title seems to be a translation of the Chinese-character phrase 枯木生花 (Korean: Go-mok-saeng-hwa) referring to something that is almost impossible to hope for, a dead tree blossoming. It is not clear if there was an old Korean novel with that title, though.

There is also, as Aston points out, a problem with the History of Korea printed with the story. Is it in fact Hong's work at all? The Japanese spellings and the inaccuracies might be signs that someone wrote it using a Japanese source . . . we will probably never know more.

T'oung Pao

1895

Vol 6 p 526 - 7

BULLETIN

CRITIQUE.

Le Bois sec

Refleuri. Roman Coréen, traduit sur le texte

original par Hong Tjong-ou (See T'oung-pao,

Vol. V, p. 260)

The Musée

Guimet, whose services in the cause of Eastern

learning are well known, has recently published a

translation into French of a Corean story under the

above title, executed by a Corean who spent some time

in Paris. This 'cher et respectable lettré', to whom a

letter addressed by M. Hyacinthe Loyson, accepting the

dedication of this work, is printed with the preface,

has since achieved an unenviable notoriety by the

murder of his compatriot Kim Ok-kiun at Shanghai.

There were no doubt attenuating circumstances. The

deed was done from political, not personal, motives

and his victim was an unscrupulous conspirator on

whose head was the blood of many men. But it was a

treacherous assassination nevertheless.

The

sketch of Corean History which is prefixed to this

romance is open to more serious criticism. It is a

very poor performance. M. Hong really presumes too

much on the ignorance of his readers when he says that

Corean History is 'totalement inconnue à l'étranger'.

This only shows his own ignorance of the works of Ross

and Griffis, not to speak of other sources of

information. Even the few pages devoted to the subject

in the 'Histoire de l'Église de Corée' are better than

M. Hong's Essay. Judging from the spelling and other

indications, it would appear to hâve been compiled, in

part at least, from Japanese sources, and is in

several particulars grossly inaccurate. It is not true

that Genghis-Khan did not molest Corea, and it is, to

say the least, misleading to assert that China

acknowledged the independence of Corea. The Treaty

with the United States was signed in 1882, and not in

1886. Germany, France, England and Russia have not

sent Ministers Plenipotentiary or Chargés d'affaires

to Seoul, but only Consuls-General. M. Hong might have

verified these points with very little trouble and his

carelessness in such matters inclines us to suspect

equal inaccuracy in places where we have no means of

testing his statements. W. G. Aston.