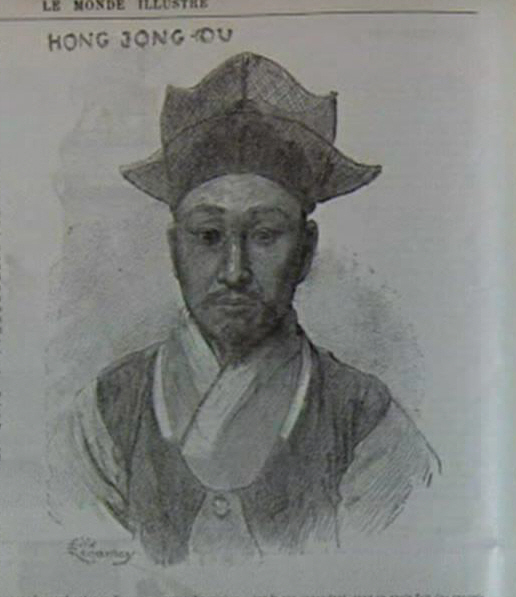

Hong

Jong-u

The first Korean

to visit France, the translator of the first Korean

tales to be published in the West, as well as the

assassin of the reformer Kim Ok-gyun, yet relatively

little reliable information about Hong Jong-u is

available in English. The main source of information

about him is a Korean volume 그래서 나

는김옥균을 쏘았다 (So I

shot Kim Ok-gyun) by 조

재곤(Jo Jae-gon) and published by 푸른역사 (Pureun yeoksa) in 2005. The page

numbers in the following text refer to this volume.

There is a

summary of the main contents (in Korean) in

Yonhap News .

Basic

Biography

Hong Jong-u (洪

鍾宇)

was born on the 17th day of the 11th lunar

month, 1850 [page 31], probably in Ansan, Gyeonggi

province. He was the only son of Hong Jae-won (洪

在源,

1827-1898), of whom virtually nothing is known. His

mother was a member of the Gyeongju Kim clan [page

63]. Hong Jong-u's Ja was

SeongSuk (聲肅), his Ho was Ujeong (羽亭), his clan was the Namyang (南

陽)

Hong clan, he was the 32nd generation (세 손) of the

military branch (남양군파). The Namyang Hong clan formed part of

the Noron (老論) Old Faction and some members held

significant posts throughout the later Joseon period,

but Hong Jong-u was descended from Hong Gye-deok (洪啓德), the third son of Hong U-sung (洪 禹崇), early in the

18th century, and none of his ancestors

during those 5 generations held any official position.

For many years, until 1894, Hong Jae-won lived in

Gogeum-do in South Jeolla, where he is said to have

known great poverty. He died in the 6th

month of 1898 and received posthumous honors as 가선대부 의정부참찬 (official at

the State Council), as part of the reward for his

son's patriotic act in killing Kim Ok-gyun.

Hong's

mother died in the 3rd lunar month of 1886.

By this time he was married to a woman from the Jeonju

Yi clan born in 1855. According to Régamey, they had

one daughter. It was probably only after his return in

1893 that Hong discovered that his wife had died in

the 11th month of 1892 (or May 1893,

according to his note to Régamey from Kobe). At

some later date he married a daughter of Park Haeng-ha

who was much younger than himself, born in 1876. They

had two sons and a daughter. The elder son, Hong

Sun-bok, was born in 1897 and the second, Hong

Sun-jin, in 1903. The daughters later married, their

husbands’ names being Kim Kyu-seok and Park Gwang-rim,

and the name of Hong Sun-jin is found once among the

members of a church in Wando island in 1926. Beyond

that nothing is known of the family’s further history.

[page 253] In the autumn of 1899, Hong arranged for

the reburial of his mother, father and first wife

together in graves located in what is now Yeoksam-dong

in Gangnam.

The

death of Hong Jong-u is recorded in the family

register (족

보

jokbo) as the 2nd day of the first lunar

month 1913. There are differing, unreliable reports of

his final years, and nothing certain is known of where

he died; Mokpo and Incheon are both mentioned. Several

reports claim that he died of starvation.

Early life

For much of his childhood, his family seems to have

lived in the island of Gogeum-do in South Jeolla,

where they barely survived, reduced to total poverty.

Yet he must have received some kind of education. In

the Preface to the Guide, Henri

Chevalier recalls that Hong told him that “in his

youth he had studied divination a lot, and that had

earned him a severe reprimand from his father, and the

burning of all his suspect books.”

Equally

significant is Régamey's summary of Hong's basic

political positions: (1) Korea should be completely

independent of China, Japan and Russia; (2) the

barriers that isolate Korea from the outside world

should be done away with. On this second point,

Regamey adds that Hong had been a friend of the first

Minister Plenipotentiary sent by Joseon to Washington,

Park Jeong-yang. He mentions that Park was recalled at

the demand of China for failing to respect the Chinese

wish that he should be subject to strict Chinese

control, since this was a time when China was

asserting its right to treat Korea as a vassal state.

Hong seems also to have expressed bitter resentment at

the British support for the Chinese position in not

allowing Jo Sin-hui (조신희), the

ambassador the Korean king had sent to Europe, to

leave Hong Kong "for 2 years" (1887 - 1890).

Hong

seems to have decided to visit France in hope of

receiving the same inspiration for democratic reform

that Meiji Japan had received. In order to earn the

fare, he went to Japan in 1888, after obtaining a

Korean passport dated 1887 authorizing his visit to

France (quoted by Régamey). He worked in Osaka as a

typesetter for the Asahi Newspaper

and raised funds by giving lectures etc. [page 64] He

studied French and Japanese and read much about the

outside world while he saved the money he earned.

Régamey reports that Hong received a letter of

introduction to Georges Clemenceau from the Japanese

politician Itagaki Taisuke.

In France

Leaving Japan for France, a 40-day journey, he arrived

in Marseille and headed for Paris. Régamey

says he arrived there on December 24, 1890. Luckily,

he had been given a letter of introduction addressed

to Fr. Gustave Mutel, a priest of the Paris Foreign

Missions, who had spent 5 years in Korea 1880-5, then

returned to France to be in charge of the seminary.

However, after the death of Bishop Blanc in Korea,

Mutel had been appointed Vicar Apostolic of Korea in

August 1890 and he left Marseille for Korea on

December 14, 1890, just as Hong was arriving. When

Hong knocked on the door of the MEP in the rue du Bac,

speaking no French, they first called the priests who

knew Chinese, to no avail. Luckily, Fr. Pierre-Xavier

Mugabure, who had lived in Japan since 1875 (and was

later to be archbishop of Tokyo), was there and they

could talk in Japanese. A Catholic family was

contacted and Hong was given an attic room in their

house in the rue de Turenne to stay in (for a while,

at least).

Félix

Régamey was inspector of drawing in the schools of

Paris at that time but, more important, he had

accompanied Émile Guimet on a

journey round the world in 1876-1877, where he was

particularly struck by Japan, and he published a

number of books inspired by it during the rest of his

life. It is an interesting fact that he was involved

in the Paris Commune of 1870 and as a result had to go

into exile in London for a time. In 1872, he provided

financial help for Rimbaud et Verlaine when they in

turn arrived in London, and made drawings of them at

that troubled time in their relationship. Félix

Régamey says he first met Hong Jong-u only a few days

after his arrival. He says Hong could speak no French,

and when a Japanese interpreter was brought in, Hong

very soon showed signs of strong Korean pride and

anti-Japanese feeling. The impression of caged fury

displayed then impressed Régamey, reminding him of a

captured tiger he had seen in Malaysia. Hong claimed

that he had come to learn French law and French

customs, but he also told Régamey that his ambition

was to become leader of a group of young people like

himself, currently residing in Russia and the US, who

wished to lead Korea in the same direction as Japan’s

Meiji reforms, an independent, modernizing

transformation. He was, it seems, especially

interested in the French political situation. Régamey

at once invited him into his home and says that they

lived under the same roof “for months.” Later he seems

to have lived in 'hotels' in rue Serpente (near the

Sorbonne) and quai des Grands Augustins.

Throughout his

time in France, Hong always wore Korean dress. Régamey

(and others) tried to find some benefactors for him,

but it is clear that few were forthcoming. There was a

fruitless visit to the aged Ernest Renan. Perhaps more

significant was the meeting with François George

Cogordan, who had been France’s Minister

Plenipotentiary in Beijing and had come to Seoul to

sign the treaty with Korea only a couple of months

after signing the Treaty of Tianjin with China. Deeply

moved to see someone he had seen in Korea, Hong threw

himself on his knees to kiss his hands, which might

have surprised him. However, the official French

attitude toward Korea at this time was oddly

indifferent; after the signing of the 1886 treaty, it

was not until 1888 that Victor Collin de Plancy was

sent to be the first French consul in Korea. Cogordan

refused ever to meet Hong again, which must surely

have humiliated him.

In

that same year, 1888, the amateur ethnographer Charles

Varat arrived in Korea, intending to undertake a study

of the country and collect many artifacts from it.

That was also the year in which Émile Guimet opened

the Musée Guimet in Paris. Many of the objects

collected by Varat came into the museum. It was only

natural, then, that Hong Jong-u should be asked to

help catalogue the Korean items in the new museum,

thanks to the help of Régamey, as a way of earning his

keep. At the same time, he somehow managed to learn

enough French to prepare translations of three Korean

texts.

The

first of these, Printemps parfumé (Perfumed

springtime, a translation of the name of Chunhyang,

the main character) was published in the the “Petite

Collection Guillaume” in 1892, and has the name J.-H.

Rosny as the sole author, although the name of Hong is

mentioned in a footnote to the Preface. J.-H. Rosny

was the pseudonym of the brothers Joseph Henri Honoré

Boex (1856–1940) and Séraphin Justin François Boex

(1859–1948), both born in Brussels. It seems that Printemps Parfumé

was in fact the work of Séraphin since La Convention

littéraire de 1935 (designed to distinguish

between the share of each in the jointly published

works) attributes it to J.-H. Rosny Jeune. The Preface

claims that the text is essentially the translation of

a Hangeul version of the Chun-Hyang story. Such a text

seems to have been available in the Musée Guimet,

included among the items sent back from Korea by

Charles Varat and Victor Collin de Plancy. The names

of the lovers are given here as I-Toreng and

Tchoun-Hyang; they meet in the city named Nam-Hyong,

in Couang-hoa-lou, which is explained as being “a

great house built on a bridge,” rather than “a

pavillion beside a bridge.” The French version does

not indicate that Chun-hyang’s mother is a “gisaeng”

but simply says that she is a commoner. One major

difference with the traditional tale is that, once

I-Toreng glimpses Tchoun-Hyang on her swing, in order

to be able to meet and talk with her he dresses as a

beautiful girl. He also pays an old woman to bring

them together. I-Toreng then says “she” would marry

Tchoun-Hyang if she were a man. Tchoun-Hyang indicates

similar feelings. I-Toreng makes her sign a paper to

that effect, then reveals that he is in fact a man.

They become lovers at once. The rest of the story

follows the familiar tale and the later part includes

social satire on the way the mandarins exploit the

common folk.

In

1895, after Hong’s return East, Le Bois Sec

Refleuri was published in the Bibliothèque de

vulgarisation, a division of the Annales du Musée

Guimet. This time, Hong’s name stands alone as

the author / translator. He must have prepared the

book for publication before leaving with some care,

since it includes an exchange of dedicatory messages

with Hyacinthe

Loyson, who mentions visits by Hong to his

family home in Neuilly. “Father Hyacinthe Loyson”

(originally Charles Loyson) was a particularly

celebrated figure in religious circles and one can

only wonder how Hong came to develop such a deep

friendship with him. The dedicatory messages have

little or nothing to do with the contents of the book,

being on both sides concerned with mutual respect and

questions of faith. Loyson had been a Catholic priest,

a Carmelite, and fron 1865 preached the lenten

Conférences at Notre Dame de Paris for several years.

His modern ideas led to his expulsion from the

Catholic Church in 1869. Some years later he married

an American widow and they finally settled in Neuilly.

He gave frequent lectures and was associated with

various “Old Catholic” groups but was essentially an

independent, spiritual man with a radically open mind.

The

truly interesting aspect of Hong’s dedication is the

concern he shows to formulate precisely his religious

ideas, in a way that clearly reflects his

conversations with Loyson. He mentions how deeply

struck he was on reading Loyson’s book (Mon testament :

Par Hyacinthe Loyson Père Hyacinthe. Ma

protestation. Mon mariage. Devant la mort) which

was only published in 1893 (an

English edition appeared in 1895).

Hong stresses in a rather un-Confucian way his

conviction that there is a God: “I believe that a

single God has given us life. He is not a strange

being dwelling far, very far away in the depths of

ethereal space in a fantastic palace built beyond the

stars. He is the Soul of our souls, the Life of our

lives, our true Father, He in whom and by whom we all

are. We are all brothers, for we are all issued from

him; but how much more do we feel united as brothers

since we both believe in him, even though our faith is

expressed in different ways.” His letter ends with the

indication that he is about to leave France and return

home; the last lines are a beautiful indication of his

deep affection for Loyson: “When you see passing in

the sky white clouds coming from the East, think of

the faithful friend who is thinking of you, far away

on a distant shore, and who is talking about you to

all the clouds and all the birds heading West-wards,

in the hope that some of them, docile to his voice,

may come and revive in you heart the memory of his

friendship.”

Unlike Printemps

parfumé, Le Bois Sec Refleuri can hardly be

considered as a “translation” in

the normal sense. It has no obvious direct Korean

original. Already at the

time, the scholarly British diplomat Aston noted in

a review (T’oung

Pao 1895 Vol 6 p 526-7), “we seem

to breathe an atmosphère far removed from Corea.”

The complex narrative

structure of Le

Bois Sec Refleuri is unlike

any known Korean original and although it owes some

features to the Sim Cheong

tale, that is integrated into a complex set of

skillfully interwoven stories

that are unlike anything found in Korea. The volume

containing Le

Bois Sec Refleuri also contains a

summary of Korean history which is far from accurate

and in which Aston already

detected a strong Japanese influence. It might seem

better to attribute the contents

of the volume (published by the Musée Guimet) to a

combination of the Boex

brothers and Henri Chevallier, and to consider the

brothers the main authors of

the tale. In one article, “Rosny” evokes Hong in his

hotel room telling them

Korean stories. The whole volume might then have

been attributed to Hong in

order to justify publication by the Museum, or to

avoid further association of

the name Rosny with a notorious “political

assassin.”

Summarized as

briefly as it can be in all its complexity, it tells

the story of two friends,

high aristocratic ministers, who are sent into

separate exiles with their wives

by the machinations of the wicked and ambitious

prime-minister Ja-Jyo-Mi. The

wife of one of them, Sùn-Hyen, gives birth to a

daughter named Tcheng-Y, then

dies. Sùn-Hyen weeps so much he becomes blind. The

years pass quickly and the

story follows that of the familiar Sim Cheong tale,

with the father rescued

from drowning by a “hermit” and told that in return

for 300 sacks of rice

prayers will be said, his sight will be restored,

and he will become

prime-minister. Tcheng-Y duly sells herself to a

group of merchants going to

China by sea, who want to offer a sacrifice for a

safe journey, and sets off

with them after arranging for her father to be cared

for.

The other exile,

San-Houni, is murdered by a wicked boatman,

Sù-Roung, who has designs on his

wife, Tjeng-Si. She escapes and along the way gives

birth to a son. She tatooes

the name San-Syeng on the baby’s arm then abandons

him by the roadside, taking

refuge in a nunnery. Sù-Roung finds the baby without

knowing whose child it is,

adopts it and brings it up well. Again many years

pass, the son learns that he

is a foundling and leaves home. Arriving in the city

of Tjen-Jou he meets a

beautiful girl whose father has died and they become

lovers; warned by her dead

father in a dream that her mother intends to kill

her lover, she sends San-Syeng

off on her father’s horse with his sword. He gives

her the ring left with him

when he was abandoned.

The king dies,

his heir is still a child. The wicked Ja-Jyo-Mi

sends him to the island of Tchyo-To

in solitary exile. San-Syeng hears of his plight,

then in a dream sees a man

named San-Houni, who refuses to tell him who he is,

but urges him to help the

boy-king. He arrives close to Tchyo-To but it is

well guarded. We now return to

Tcheng-Y, who jumps into the sea but does not sink

down to the Dragon King.

Instead she lands on the back of a giant turtle that

carries her to a cave

beneath an island. She climbs up to the surface and

finds herself in a

beautiful garden; here she meets the exiled

boy-king, Ki-si,

and they fall in love. Fearing that he will be

killed, they set fire to the

house and flee down the cave to the sea but there is

no boat in sight. San-Houni

again appears to San-Syeng in a dream and tells him

to take a boat to the

island quickly. There he rescues Ki-si and his wife.

The population rebels

against Ja-Jyo-Mi, Ki-si is hailed as the new king,

the prime-minister is

arrested, and the new king sends San-Syeng as a

secret inspector to check the

quality of the local governors.

We return to San-Syeng’s

lover-wife, Tjyang-So-Tyjei, whose mother has died

and who has lost everything

in a rebellion. She arrives near the nunnery and is

discovered by Tjyeng-Si,

San-Syeng’s mother, who recognizes the ring. They

identify themselves and set

out in quest of San-Syeng. Reaching Saug-Tjyou,

Tjyang-So-Tyjei refuses the

advances of the inn-keeper’s son, is framed by him,

is arrested, and finds

herself in the situation of Chun-Hyang, when the

magistrate gives her the

choice between marrying him and death. Meanwhile

San-Syeng has found Tjyang-So-Tyjei’s

house empty, in ruins. San-Houni appears in a dream,

reveals his identity as

San-Syeng’s father and tells him what is happening

to Tjyang-So-Tyjei. San-Syeng

arranges to be put in the same prison, his horse is

recognized by Tjyang-So-Tyjei,

all are reunited, the role of San-Syeng as secret

inspector is revealed, the

magistrate is punished, Sù-Roung is also arrested.

When Tcheng-Y,

now queen, hears all this she recalls her blind

father, a feast is held for the

nation’s blind men. Sùn-Hyen finally arrives, very

dirty, but when a palace

lady criticizes him he makes a very eloquent, wise

and poetic reply which is

reported to the queen. They meet, his eyes open, he

meets San-Syeng and learns

that he is the son of his old friend San-Houni.

Sùn-Hyen is made prime-minister.

Finally, the king wishes to wage war on the Tjin-Han

who defeated his father

once, and there is still the question of the

punishment for Ja-Jo-Mi and

Sù-Roung. Sùn-Hyen asks the king to hold a great

banquet for the whole

population, saying that they should support whatever

is decided, war or peace,

punishment or forgiveness. He makes a speech in

favor of peace and

reconciliation, all agree. Finally he vanishes,

perhaps taken up to heaven on a

cloud.

The

third work translated by Hong was very different, an

astrological treatise of divination, Guide pour rendre

propice l'étoile qui garde chaque homme et pour

connaitre les destinées de l'année, only

published in 1897, again in the Annales of the

Musée Guimet, with the name of Henri Chevallier

added to that of Hong as author / translator. In a

preliminary article about this book, published in Volume

VI (1895) of T’oung

pao Henri Chevalier explains that the book

had been brought back from Korea by Charles Varat and

Hong had begun to translate it at the request of

Guimet. His departure interrupted the project and

Chevalier had taken it over. Chevalier was originally

an engineer who worked for some time in Japan, who

later developed an interest in oriental languages.

Hong

must have moved out of Régamey’s house at some point,

since Régamey says they only met again shortly before

Hong’s departure, when he needed money for the journey

home. His description of Hong’s extreme reserve when

they parted suggests that he was deeply hurt that Hong

expressed no gratitude for all his help and

friendship.

As

we read Régamey’s

description of Hong in Korean robes being driven

away, smoking a cigarette and not even looking back to

wave goodbye, having spent 2 years cataloguing Korean

artifacts, and translating Korean texts, it becomes

clear that he had made no attempt to learn about

French law or politics. Instead, during those years,

Hong had focused on aspects of his own culture, and

may well have become more strongly aware of the

imperialism of France and the other western countries,

realizing that Korea would not be able to rely on

outside help from any quarter. Where Kim Ok-gyun

looked to Japan as a model for Korea’s future,

accepted Japanese financial help, had taken a Japanese

name and seemed unwilling to recognize the threat

Japan’s colonizing intentions posed to Korean

independence, Hong had moved in the opposite

direction.

Three shots in Shanghai

Hong Jong-u left Paris on July 23, 1893, headed for

Marseille. There he boarded the steamship Melbourne

and returned to Japan. [page 95] Régamey ends his

article with the note he received from Hong after his

return, written in awkward French, in which he reports

having been sick for some time after his journey and

adds the news that letters from his father and friends

had informed him that his “poor wife” had died “in

May” (by implication 1893). In December 1893, Hong

received a visit from Yi Il-jik, who in April 1892 had

been charged by the Min faction in Seoul to kill the

refugees from the 1884 Gapsin Coup: Kim Ok-gyun, Park

Yeong-hyo, Jeong Nan-kyu, Yi Gyu-wan, Yu Hyeok-ro etc.

Yi told Hong that it was the wish of the king himself.

Hong agreed enthusiastically, it seems. His first task

would be to become acquainted with the Gapsin

refugees. It was agreed that Hong’s task would be to

encourage Kim Ok-kyun to travel to China, and kill him

there since he was well-protected in Japan.

Hong was quite easily able to meet the refugees

and join their gatherings on the basis of his family

clan identity. He is said to have gained Kim’s trust

especially by preparing delicious food in the French

style for him and his Japanese friends in Tokyo. At

the time, Kim Ok-gyun had been living In Japan for

nearly ten years and was not sure that the Japanese

would go on protecting him indefinitely; at the same

time, he seems to have abandoned his strongly negative

attitude to China and begun to formulate a vision in

which Korea, China and Japan would best ensure their

separate independent status by combining to resist

attempts by the western powers to dominate them.

Meanwhile the Japanese were already preparing to wage

war with China and take a more complete control of

Korea; it began to seem to them that the death of Kim

in China at Korean hands might serve a useful purpose.

This would explain why Japan did nothing to warn or

protect Kim after receiving a report written by Nakaga Kotaro (中川 恒太郎) its consul in Hong Kong on

January 1, 1894, describing words spoken that day by

Min Yeong-ik, the Korean Queen’s nephew, to a group of

his supporters there, advocating the assassination of

Kim Ok-gyun etc. and even telling them that in Osaka

Yi Se-jik [sic] with a Korean recently returned from

Europe, named Hong Jong-u, were actively engaged in a

plan to that effect. [page 106].

Indeed,

the Japanese government had always been less than

enthusiastic about the presence in Japan of the Gapsin

leaders and it is not always realized that Kim Ok-gyun

was humiliated by being forced to spend some 3 of the

9 years he spent in Japan detained in the Bonin

Islands and Hokkaido, far from Tokyo. Moreover, he was

reduced to political silence, his days were spent

eating, drinking and playing Baduk with a few friends.

He quickly understood that Korea could expect nothing

good from Japan and in mid-1886 had already written to

the Korean King warning him against the ambitions of

Japan and China. But for the Korean government he was

a traitor, nothing more. Finally, Kim seems to have

decided to explore the possibility of a visit to

China; he had been living with the Japanese name Iwata

Shusaku (岩田 周作) but now

changed that to Iwata Miwa (岩田 三和). The use of

the character for “3” symbolized his new vision of a

reconciliation between the three nations of the

region. Kim decided to travel to China to meet the

great Chinese politician Li

Hongzhang. He had been close to Li’s

adopted son (his nephew) Li Jingfang (李經方) while he was Chinese Minister in Japan

1890-1892 and there might have been some preparatory

correspondance between them.

Many

of Kim’s associates urged him not to go, some did not

trust Hong although Kim Ok-kyun seems to have rejected

their warnings. So he and Hong traveled together with

Kim’s servant and a translator from the Chinese

legation. They reached Shanghai on March 27, 1894, and

lodged in separate rooms of the Towa yoko 東

和洋行Japanese-run ryokan in Shanghai. The

following day, Hong went out to change money, then

returned while Kim was resting in his room during

the afternoon and shot him three times with a

revolver. Kim died almost instantly. That was just

after 4 pm. Hong then fled and was arrested the

following afternoon. He changed into Korean robes

before killing Kim.

Questioned

by the police, he said he had killed Kim, first,

because he and the other Gapsin conspirators had

caused the deaths of many innocent people; second,

that he was obeying a royal command. The third reason

was that Kim was a threat to the peace of the region,

as well as a traitor. Li

Hongzhang decreed that Kim had been a

Joseon traitor and Hong a Joseon official, so both

should be sent back to Joseon at once. Newspaper

reports about this are quoted at the end of the

article by Félix Régamey, who finds himself at a

loss to understand what Hong had done. On

April 12 Hong and the corpse arrived at Incheon, where

they transferred to a boat for Seoul. During the

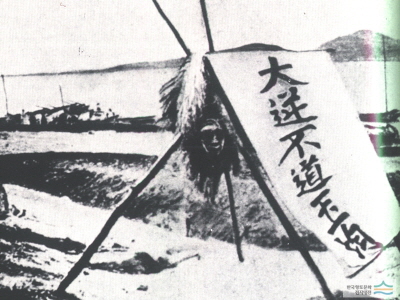

journey, Hong had written on a banner the characters 大逆不道玉均 (Traitor Ok-gyun). The body of Kim was

left at Yanghwajin, down-river from Mapo at what is

now Hapcheong, where it was beheaded, the hands and

feet removed, and the trunk mutilated. The parts were

sent around the country for display. There is a photo

of the head with Hong’s banner. Other measures were

taken to punish surviving and dead participants in the

1884 coup, while the families of those officials

killed by the conspirators celebrated. In Japan, the

press launched a campaign acclaiming Kim as a hero and

denouncing Hong as a monster.

The short article signed J.-H. Rosny from

Le Carillon du Boulevard Brune, 1st year,

number 11, May 1894 indicates how perturbed Hong's

French friends were on hearing what he had done (original

French text with English translation). There is

no sign that the Japanese romance mentioned in this

article was ever published. Trying to understand

Hong's deed, Rosny speculates: “Arrested after the

murder by the European Police of Shanghai, Hong

Tjyong-Ou called for Chinese justice, claiming to have

killed Kim-ok-kium on the express orders of the King

of Korea. Kim, he added, is a traitor. The excuse

would be of little value to us if Hong Tjyong-Ou was

merely obeying his king; he had no personal reasons to

believe in the perfidy of Kim-ok-Kium. We remember

that Hong Tjyong-Ou spoke frequently to us of the

violence of Kim-ok-Kium and the following words of Kim

to Hong when they parted: Hong - said Kim, - if you

ever change opinion, I will kill you! However,

Hong Tjyong-Ou in contact with European civilization

had changed his opinion. He placed no hope in

violence, he did not accept Japanese armed

intervention. On his return to Japan, did he try to

convert Kim? Did Kim make threats? Did he denounce

Hong to the terrible vindictiveness of the Japanese?

Did he he perform acts or speak words, which indicated

high treason? Was Hong Tjyong-Ou forced to pretend in

order to save his life? Did he repay Kim perfidy for

perfidy?” Some time later, in

another essay, Rosny offered a more nuanced and

more detailed portrait of Hong and his inner world:

"Et tout d'abord le Coréen lui-même, dans une attitude

hautaine et sage et une figure de conviction, fumant

sa cigarette, la peau luisante à gros grains, les

paupières grasses, les yeux bruns semblables à ceux de

nos yeux bruns qui sont plus spécialement des yeux

d'intimité et d'intelligence, des yeux qui ne tirent

point une beauté du dehors, qui n'éclatent pas ainsi

que des bijoux clairs ou de noires étincelles, mais

qui ont, dans l'iris, une lumière soumise depuis des

siècles à des lois sociales, à une discipline de mots

et de pensées. Cela ne va point sans un peu de

férocité, si raisonnable soit-elle, et, à l'occasion,

le morigénateur consciencieux, le moraliste à la

Confucius saura accomplir le meurtre avec une

résolution digne de Patrocle ou d'Ulysse. Oui, une âme

d'enfant guidée par des conseils de vieillard, telle

est l'âme du Coréen, telle est peut-être l'âme de tous

les Jaunes. Ils ont encore la violence des temps

héroïques côte à côte avec le joug des préceptes et

des sentences."

After Shanghai

There is no way of knowing the precise reasons behind

Hong’s attack on Kim Ok-gyun. Was he sincerely devoted

to the King and convinced that Kim deserved to die, or

was he driven by opportunism? In particular, the

indications by Rosny that Hong was well acquainted

with Kim Ok-kyun before he arrived in France, that he

often spoke of him and that he had been one of his

close collaborators at the time of the Gapsin coup,

are aspects that are not even mentioned by the Korean

study of his life. Certainly, Hong had come back from

France empty-handed, and had no prospects of work in

Korea. This was the ideal opportunity to establish

himself. Whatever his intention, once back in Korea,

Hong was soon the toast of the town. He was reportedly

hailed by Gojeong himself, who came running out of his

rooms in his stockinged feet on hearing he had arrived

in the palace. Hong at once became a government

official by special royal decree. However, in the

months that followed, everything went wrong. The

Sino-Japanese War ran from 1 August 1894 until 17

April 1895. During that time, pro-Japanese forces took

power in the government and Hong seems to have taken

refuge in China. After the murder of the queen by the

Japanese in October, 1895, power returned to the

conservative side and Hong must have returned from

abroad. From February 11, 1896, until February 20,

1897 the King was living in the Russian Legation and

in the late summer of 1896 Hong seems to have helped

mastermind the arrest of the pro-Japanese officials

who had lost power a few months earlier. They were

released in the autumn and became involved in the

foundation of the Independence Club. Meanwhile, Hong

had gained considerable influence with the King and

advocated strongly the imperial model of power

centered in the King which inspired the creation of

the Korean Empire. Late in 1896, Hong was appointed

head of the foreign affairs section of the palace

administration. Early in 1897, when the Japanese

Minister came for an audience, Hong was seated

directly beside the King. In the following time, he

played a major administrative role in setting up the

structures of the Korean Empire and was responsible

for composing the new law code.

The list of his promotions and career changes from 1898 until 1902 shows how powerful Hong became in the early years of the Korean Empire. At the time when the Korean Empire was etablished in August 1897, Hong was acting as a member of the State Secretariat (비서원승), but by 1898 he was also Secretary General of the State Council (의정부 총무국장), Director of Regions, State Council (의정부 지방국장), General Director of the Department of Farming and Sericulture (농상공부 광산국장), member of the Jungchuwon Advisory Council (중추원 의관), then in 1899 he served as Secretary General of the State Council (의정부 총무국장), Judge of the Pyeongni-won Supreme Court (평 리원 판사), in 1900 Head of the Sariguk division in the Justice Department (법부 사리국장), Chief Justice of the Pyeongni-won Supreme Court (평리원 재판장), in 1901 Member of the Council of Rituals (봉상사 부제조), member of the Jungchuwon Advisory Council (중추원 의관), in 1902 he was Palace Administrator (태 의원 소경) and so held controlling positions in the departments of diplomacy, justice, administration, administration of legislation, industry. Hong, together with two other men of humble origin, Gil Yeong-su and Yi Gi-dong, known as the “Hong Gil-dong trio” enjoyed unrestricted access (별입시) to the Emperor and exercised immense influence.

One

reason for Hong’s final downfall is easily summarized.

He was completely unable to understand or sympathize

with the growing demands of the international business

community and opposed many financial and

administrative measures which others judged essential.

One

episode from this period is of special interest. In

1899, Hong Jong-u was presiding judge of the high

court known as the Pyeongniwon. This was the time of

the conservative crackdown on the members of the

Independence Club at the end of 1898 and among those

on trial was a young student, Yi Seung-man, better

known in later times as Syngman Rhee. As the head of

the Hwangguk

Hyophoe (Imperial Club), he and Rhee were

diametrically opposed. At that time, Rhee might easily

have been sentenced to death, yet Rhee later wrote how

amazed he was to find Hong determined to save his

life; instead he was sentenced to 100 blows on the

buttocks and life imprisonment. He also wrote that

Hong gave orders to be gentle when the beating was

performed, so that after the 100 blows his skin was

not even broken.

There

was, however, no resisting the slow increase of

Japanese control and the rise of officials prepared to

work with Japan. The result was his appointment in

January 1903 as 牧使 (moksa,

magistrate) of Jeju Island. Dealing with the

aftermath of the violent disturbances of 1901,

focused on issues of taxation and involving the

Catholic community with its French priests, might

have been one reason for his appointment, but he

seems to have understood that it was a kind of

exile, the beginning of the end. There are

indications that he demanded bribes and made no

attempt to help the population in times of poor

harvest; he was probably mainly intent on securing

funds for a bleak future. In the spring of 1905 he

resigned from the position and went to live in

Muan-gun near Mokpo. He was still residing there

early in 1909, and after that there are no reliable

records of his final years. According to his clan

register, he died on the second day of the first

month of 1913, but there is no record of where.

Rumors say that he starved to death