Voyage en

Corée 5. (Voyage in Corea Section

5)

by

Charles

Varat

Explorer

charged with an ethnographic mission by the

minister of Public Instruction

1888-1889

— previously unpublished text and pictures

Le Tour du Monde, LXIII,

1892 Premier Semestre. Paris : Librairie

Hachette et Cie.

Section Five. [Click here for the other sections in English: Section One; Section Two; Section Three; Section IV.] Engravings (all)

A Korean menu. - Aesthetics. - Dogs and

cats. - Departure from Mil-yang. - Valleys and rice

fields. - Tributes to old age. - Koreans and

Japanese. - Waterscapes. - The Tchung-ka-rnœ-san. -

At a Japanese hotel. - Farewells from my caravan. -

How the mousmes smoke. - Mandarins, Europeans and

Japanese. - The four Fou-san. - Navigation on the

east coast. - Gen-san and Tok-Ouen. - Tigers. -

Vladivostok. - Koreans in Siberia. - A typhoon in

the Korea Strait. - Nagasaki. - Conclusion.

We settle in at the inn, and as

Mil-yang is the capital of a large district, I

immediately send my Korean card to the mandarin who

administers it and I soon learn that this officer is

absent from the noble gentleman who is replacing him

and comes to visit me. I offer a European collation;

it seems quite to his taste, because he does full

honor to it, warmly thanks me and apologizes for not

inviting me to his home, his father being ill. The

same evening he sends me an excellent Korean dinner

served in pottery vases of great price. Here is the

menu: a rich soup with wheat, pickled fish, beef cut

into tiny oval slices, chicken also cut into pieces,

game likewise, etc.. All this is accompanied by

cooked turnip, a leek salad mixed with a pleasant

yellow liquid, in addition, for seasoning other

dishes, soy-bean sauce, exquisite like that

manufactured in Japan, and small bowl with a

delicious sauce that I am told is Chinese. The meal

is completed by mouth-watering cakes, fine sweets,

fruits: apples, pears, persimmon, etc. Finally, to

wash it all down, a very elegant porcelain bottle

filled with a delicious rice wine, similar to that

which I was offered by the governor of Taikou.

Korean wine, red or white, is extracted from rice,

wheat, etc.., and has a fine transparency, obtained

by throwing in a glowing ember at the end of the

fermentation. It is much superior to that

manufactured in China or Japan, and reminds me very

much of our grape wine, with a kind of strange

velvety smoothness that pleases the palate. Although

it is very alcoholic, I find it so excellent that I

want to send some to France for my friends, but I

have to give up the idea because it keeps for a very

short time and is not transportable. This luxurious

Korean meal is accompanied by a huge bowl of boiled

rice which replaces bread; the water that is removed

from it is the ordinary drink, tea being an extra

for most Koreans. I admit that, despite all the

culinary skills that have been spent on me, I

prefer, as a mere matter of digestive habit, a steak

with fried potatoes to this mandarin meal, although

I should add that between the elaborate cuisines,

Chinese, Japanese and Korean, I prefer the latter.

The same evening I send my thank you card to the

noble Korean who responded in so kind a way to my

European collation, and I offer the remains of my

meal to my two soldiers. They assure me that they

have never eaten anything better in their whole

lives. I dismiss them and shut the door of my room.

My furniture is increased by a small

Korean screen 1 meter high by 3, that I buy along

the way. It is very old and consists of eight

panels, each of which bears the Chinese character of

a virtue that a man must practice: filial piety,

ghai; deference, tche; loyalty, tchoug; confidence,

tching; politeness, rey; probity, ry;

disinterestedness, vom; modesty, tchy; these

qualities are represented again, as usual, by

animals or symbolic objects whose brilliant colors

light up my diminutive quarters. While outside the

rain falls in torrents with a disturbing continuity,

I seek oblivion by admiring my screen, which, in

addition to all the virtues it wishes its owner,

also offers, from an artistic point of view,

valuable information on the origins of Korean art.

More precisely, a small purple frame rimmed with

white surrounds each panel except for the lower

part, which ends with a broad black band with

another white, across which runs a light blue

geometric design. There is the same repetition in

the upper portion, where there is added a narrow

black strip highlighted by a wine-red line, which

circumscribes the entire panel. The latter, straw

white is loaded with large archaic Chinese

characters drawn largely and of rare calligraphic

merit; they stand out vigorously in black ink on the

light background on which are painted, below or

around them in very pale colors, the allegorical

attributes of each of these signs. Despite the shock

of such contrasting tones, a true harmony emerges,

thanks to the support of the broad black stripes of

the frame. As for the attributes, in addition to

their delicate nuances, they are characterized by

the hieratic quality of their lines, and in the

representation of flowers and even symbolic animals

can be found the drawing at once geometric and vague

of the artistic products of Persia and India. Such

are the original sources from which the Koreans have

been able to achieve a truly national art. We had

already realized this as we admired the beautiful

arrangement of the palaces and the main monuments of

Seoul, the painting of the pavilions over the gates

at Taikou, the beautiful costumes of the court of

the Governor, the picturesque sculptures and

architecture of Mil-yang, in short, all the manual

productions and even the monologue-drama, all so

alive, so human, so personal. Thereupon I blow out

my candle and fall asleep smiling at the thought

that people had depicted these gentle Koreans as

veritable savages.

The next morning, I get up very early

and await a brightening in the weather in order to

photograph the major landmarks and the very curious

aspects of Mil-yang. After two hours of waiting, I

can finally go out and start to operate, to the

great astonishment of a section of the population,

that my two soldiers keep at the necessary distance

from my camera. A dog of medium size, with yellow

hair and green eyes, as often found here, follows me

everywhere, because I stroked it, something that the

Koreans never do. I think I have found the reason

for this repulsion, strange among people who love

animals: it comes from the fact that a number of

children running naked through the fields are

mutilated by dogs. To reduce the frequency of these

accidents, they accustom the boys to throw stones at

them, so that later, having become men, they pursue

and curse these unfortunate quadrupeds. They,

repulsed by everyone and living half wild, then see

the aversion they inspire further increased by the

countless ticks, small brown spiders the size of a

pea, which, armed with short legs swarm freely in

their unkempt fur. They are nevertheless very

intelligent, and those in Seoul know very well how

to open for themselves the small flap provided for

them at the bottom of each gate and the shutters

that reinforce them by night. This allows them to go

in and out at all hours and escape the cudgels of

the Koreans, who, like the Chinese, mainly

appreciate this animal in the form of stew and most

especially as chops.

But it is time to move on: we set off,

warmed by the sun that has finally emerged from the

clouds which intercepted its rays. The entire

countryside, refreshed, shines with a thousand

sparks, illuminating all around us the trees, the

farms with their beautifully cultivated fields,

groves of trees. I look back and, taking one last

look at the walls of Mil-yang, I find traces of the

many battles against the Japanese they once endured.

Like the flocks of birds that we often encounter

heading south-east, the invaders also fled, not

because of the harsh climate, but faced with a whole

people that rose up to regain its independence. May

we one day see such a migration in our land!

After leaving Ori-chang and passing the

Sain-tang and the Kufa, tributaries of the

Nak-tong-yang, we move away from the river and pass

several important towns, including Tang-yori-tchou,

at the entrance which we often find votive chapels

erected in honor of those men or women who have

distinguished themselves by their patriotism, filial

piety, who fulfilled their paternal, maternal or

fraternal duties, even widows whose virtue was the

honor of their sex: glorious shrines destined to

inspire in every heart the family virtues, that are

the basis of Korean society. We are now in a vast

plain, bounded by a chain of hills; the rice fields

that surround us are a huge checkerboard where many

workers, immersed in water up to their knees, are

engaged in hard work. The curiosity excited by my

passing makes them pause for barely a moment in

their work, that they immediately resume, so active

is the Korean farmer. From time to time the soldier

who is leading the convoy asks the way or rather

which of the small ridges emerging from the rice

field is the one that must be followed, and seen

from afar our caravan seems to be walking on water.

Everyone hastens to inform us by voice, but mainly

by gestures, because since we left Taikou and began

moving towards the south, the language of my men is

less and less understood, in consequence of the more

pronounced dialect.

Here comes, advancing toward us, a

great and majestic old man, walking solemnly

supported by a long, very elaborately carved walking

stick, in Korean called "cane of old age." At the

approach of this ancestral figure, everyone, in

order to free the narrow path he is following,

advances without hesitation knee-deep into the rice

field and respectfully bows; I too direct my horse

into the water, happy, in following their example,

to thus pay my European homage to the majesty of

years. Old age is a doubly sacred kingship in Korea,

for if the ancestor has a right to the filial piety

of each one, he must also be for all and especially

for his family a true father; if some selfish person

fails in this, the Mandarin knows how to recall him

to virtue, without lacking in the respect due to old

age. I reproduce here a curious example: "Lately,

wrote in 1855 Bishop Daveluy, “a young man of twenty

years was brought before a mandarin for a few francs

that he owed in taxes and was unable to pay. The

magistrate, warned in advance, arranged the matter

in a way that was much applauded. "Why have you not

paid your contributions? he asked the young man. – I

have difficulty in earning a living by my days of

work, and I have no resources. -Where do you live?

-On the street. – And your parents? – I lost them in

my childhood. – Is there no-one left in your family?

– I have an uncle who lives in such a street, and

lives off the income from a small piece of land he

owns. – Does he not come to your help? – Sometimes,

but he has obligations, and can do very little for

me." The mandarin, knowing that the young man spoke

thus out of respect for his uncle, and that in

reality he was an old miser, very well-to-do, who

had abandoned the poor orphan, continued to question

him. "Why at your age are you not yet married? – Is

it so easy? Who would want to give his daughter to a

young man without parents and in misery? – You

despair of ever getting married? – It is not the

desire that I lack, but I do not have the means. –

Well, I'll take care of that, you seem an honest lad

and I hope to find a solution; find a way of paying

the small amount that you owe the government and I

will summon you again soon." The young man withdrew

without knowing what all that might mean. A report

of what had happened in open court reached the ears

of his uncle, who, ashamed of his conduct and

fearing a public affront from the Mandarin, could

find nothing better to do than to take immediate

steps to marry his nephew. The matter was quickly

settled, and the date for the ceremony fixed. The

day before, when the hair of the bridegroom had

already been fixed in a top-knot, the mandarin, who

was kept informed of all, summoned him to the court

and bade him pay the money he owed in taxes. "Why,

said the mandarin, you hair is up; you're already

married? How did you manage to succeed so quickly? –

A suitable match was found for me, and since my

uncle could give me some help, things are concluded:

I'm getting married tomorrow. Very well, but how

will you live? Do you have a home? – I do not try to

foresee things so far ahead, I'm getting married

first, then I will see. But in the meantime, where

you will be staying with your wife? I'll find a

little corner in my uncle’s house or elsewhere to

lodge her until I have a house of my own. And what

if I had a way to make you have one? You're too good

to think about me, it will work out gradually. But,

how much would it take to accommodate you and set

you up properly? – No small amount, I would need a

house, some furniture and a small piece of land to

cultivate. Would 200 nhiangs (400 fr.) suffice? – I

believe that with 200 nhiangs I could manage very

nicely. –Well, I'll think about it; get married, get

on well together and be more punctual in paying your

taxes." Every word of this conversation was repeated

to the uncle and he saw that unless he paid up he

risked becoming the talk of the whole town, so that

a few days after his wedding the nephew had at his

disposal a house, furniture and the 200 nhiangs of

which the mandarin had spoken." Do you know, reader,

another country where the duties of the family are

so well understood by all that it is sufficient,

when someone forgets them, for justice to appear

informed for order to be immediately restored?

Soon we leave the rice fields and come

closer to the hills by a semblance of road that many

Koreans are taking. Thus, as we come closer to the

sea, a movement of increasingly intense human life

follows our almost complete isolation in the

mountains. In the villages through which we now

pass, all the agricultural implements used to

prepare the rice are in motion. The feverish

activity prevailing in this district comes from the

fact that its inhabitants, who alone escaped the

drought, are hoping to help the neighboring county,

where soon famine will spread in all its horror. At

last we reach the direct route from Seoul to Fu-san,

and there before me, to my great amazement, I see

the telegraph poles recently established in Korea,

like in Japan and China. From time to time we meet

some Japanese merchants from Fu-san who have come

here on some business. These little men, usually

very ugly, wearing long dresses with wide belts,

boots of Pont-Neuf style and small round bowlers in

Belle-Jardiniere manner, have a strange effect on me

in the midst of this tall and strong population in

their very particular clothes. It seems to me that

before long we will see that the Koreans are in no

way inferior to their neighbors when it comes to

progress. Although the Japanese, of whom they were

once the educators, today surpass the Koreans in the

point of view of industry and the arts, they will

soon catch up and go beyond them, through their

moral superiority. That is attested by the admirable

organization of their family, their solidarity,

their energy at work, and finally the amazing

progress they have made in recent years, as

evidenced by the telegraph, the civilizing lines of

which will soon spread throughout Korea.

We are now surrounded by lovely hills,

from which escape hundreds of streams that spread

across the valley, where they form a watery

landscape, so that we are all the time fording a

multitude of small rivers, where my horse nearly

drowns at one point. We stop for lunch at

Sang-san-natri, in a hostelry at the end of the

village and close to a wide creek in which some

peasant women are washing clothes, which is not a

small matter, given the many undergarments of Korean

women and the white clothing worn by almost all the

men. All these clothes, laid out on the ground to

dry in the sun, give at first view the impression of

a snow-covered field standing out amidst a verdant

landscape; it is a delightful sight, viewed from the

window of the room where I take my meal.

As soon as our horses have been fed, I

hasten to set off, in order to reach Fu-san the same

evening, and I do well because, after passing a

series of hills, we arrive just before nightfall at

the foot of a quite high pass, the Tchung-ka-moe,

which stands right in front of us. The ascent is all

the more difficult as there is no path through the

sprawling rocks that obstruct our progress. I could

not complete my journey with a more difficult pass.

Twice, our caravan suddenly finds itself on the edge

of a frightful abyss, which in the dark could have

been our loss. We now dominate half the deep valley,

over which huge rocks seem suspended, likely at any

moment to fall and crush with their dark mass the

small village that lies at the bottom of the valley,

where a foaming torrent roars among the rocks. The

setting sun illuminates this landscape, like the

scenery for some great opera, with the most vivid tones;

it is a splendid sight. Soon, bathed in the last

rays of daylight, we finally reach the longed-for

summit and enjoy suddenly, on the other side of the

mountain, a night studded with stars. The descent is

slow along a real road, along which we are preceded

by a local inhabitant who I had taken as our guide

on account of the darkness. We reach the plain and

finally arrive at a wooded hillock by-passed by an

avenue of magnificent cedars, from where a steep

slope leads to the entrance of Fu-san. There we

cannot make ourselves understood, because the

dialect of the east coast is completely different

from the language commonly spoken in Korea.

Therefore, in a general embarrassment, all my men

gather around me and claim that, having managed to

travel in their country, that I did not know, I must

do the same here. The case is fairly general, as our

guide says that there is no inn in Fu-san. Unable to

get from him, given his patois, any other

information, it is with the greatest difficulty

that, helped by my interpreter, I give him the order

to lead us to the foreign concession. I enter with

him into the city, and finally arrive at the office

of the Japanese police, where a very friendly

employee, with whom, thanks to writing in Chinese

characters, we can finally communicate. He tells me

of a Japanese hotel where I can lodge with my

luggage, but the caravan will, because of the

horses, have to find accommodation five kilometers

away in the Korean town. A few minutes later, we

arrive at my hotel.

It's time to dismiss my people, who had

already received part of their pay on leaving Seoul

and in Taikou. I pay the full amount due, add a

large tip which is doubled for the little orphan,

who, given the season, definitely needs warm

clothes, and ask my men to kindly take him back with

them to save him from starvation. They promise me to

do so and take their leave, thanking me a lot, and

it is with a real sense of sadness that I say

goodbye to these good people, who seem equally upset

by our separation. Then comes the turn of my two

soldiers and my cook. I suggest they go back to

Seoul by way of sea or by land along the direct

postal route, much shorter than the path we have

traveled; in the latter case, they will benefit from

the cost of their transportation, their I will pay.

My soldiers eagerly accept my latter proposal. I

later learned of their safe arrival in Seoul,

several days before the ship they would have had to

wait for here. As for my master chef, he hesitates,

but a few hours later, having found employment with

the Chinese consul at Fu-san, he receives the price

of his fare, which is thus pure profit for him.

There remains my interpreter; having little

curiosity about the things of this world, but being

a good father, he refuses the overseas journey I

offered to enable him to make with me; he prefers to

receive the amount and go back to his family. All

these questions settled, I go to my room, quite

upset by all these farewells. Tt shows on my face,

so that the two small mousmes waiting for me to

serve my dinner are quite at a loss: people are so

rarely sad when they arrive in a Japanese hotel!

We crossed completely Kyeng-Syang-to,

so let me say a few words about this beautiful

province. It is bounded on the north by

Kang-Ouen-to, on the west by Tchyoungtchyeng-to and

Tyen-la-to, on the east by the Sea of Japan and on the south by the Korea

Strait. It is contained to the north by the mountain

chain of Syo-Paik-san, on the west by the

Song-na-san, who also has other names, and to the

east by Oun-mou-san, which also has various names.

All these chains joining to surround it on three

sides and form the basin of the Nak-tong-kang with

its many tributaries and sub-tributaries. The

natural products of this province are very similar,

as we have seen during the course of our trip, to

the products from Japan. There are many ancient

architectural remains that indicate the important

role it has played in the history of Korea: in fact,

it is the ancient land of the Tchen-han, who later

became the Kingdom Sia-lo, whose founder Ao-ku-sse

made of Taikou his habitual residence and installed

his court there. Some authors believe rightly that

the kingdom of Sia-lo is none other than the Si-la

where the Arabs established important trading posts

in the tenth century. It was the bulwark of Korea at

the time of the great Japanese invasions, especially

in the third century, during the expedition

commanded in person by the Japanese princess

Zin-gul, who had donned the clothing of her husband,

and those of the famous sio-goun Hideyosi in 1592

and 1597. This province is now divided into 4 fok (mou)

or large prefectures; —11 fou or

departmental cities; —14 kou (kiun)

or principalities; —1 rei (ling)

or jurisdiction; —34 ken (kian)

or inspectorates of mines and salt works; —11 yk or

postal directorates; —24 fo (phou)

or strongholds; —2 generals commanding the troops;

—2 kou-kö

(yu-hsou) or dukes; —2 Navy commanders; —2 prefects

of general police; —10 man-ho

(wan-hou) or heads of 10,000 men; —6 directors of

customs. The population is estimated at 430,000

inhabitants according to the official documents of

which we have spoken. It can be almost doubled for

the reasons given above.

While I put in order the notes taken

during my trip, my two little mousmes sitting on the

floor look at me curiously, offer me, when it is

needed, a light for my cigarette, and, as I have

authorized it, smoke their own tiny pipes. When they

have lit them, there is nothing more curious than

their pretended assaults of politeness: they gently

wipe the pipe end with tissue paper, offer them to

each other with a smile, make the exchange with a

graceful bow of the head, then inhale a long breath

of smoke and let it slowly escape into the air in

the most flirtatious way in the world, in short,

while they play this little elegant-Japanese game,

they are delightful. But now the paper-lined door

slides open in its groove; my interpreter appears

and tells me that the two mandarins representing the

Korean government in Fu-san have come to visit me

upon receipt of the card that I had the honor of

addressing them. I invite them to come in, thank

them for their kind visit, and invite them to take

with me a European collation. They agree, and I have

no need to explain anything because, having lived

for some time in the concession, both are accustomed

to our habits. They congratulate me on my journey,

made by a European for the first time, and offer

their services in any way possible while I am in

Fu-san. I express my gratitude, and they speak to me

of Europe, ask me a thousand questions, particularly

if I have photographs of my country. I tell them no,

but I can show them some of America. Our mandarins

are absolutely stunned by the houses of ten and

twelve floors in New York and ask me to explain how

it is possible to build such monuments, the height

of which they can perceive, thanks to the people

they can see at the windows. So we spend a

delightful time together, and they withdraw after

inviting me to take tea the next day at their home.

I responded to this invitation, and I could see once

again how quickly the Korean adapts to our customs,

for they received me in European style, even

offering me champagne. I think this is a new

business opportunity for our rich province, for I

found in all the mandarins a fondness for that most

gay of our French wines. Our guests have only just

left when I am handed the card of Mr. Civilini, of

the Korean customs service and in charge of the port

of Fu-san. Delighted to meet a European, I go out to

welcome him. This excellent man had just met my

caravan and having thus learned of my arrival, had

hastened to inquire how he could help me, ready to

help in any way, he said, after the curious journey

I have ventured to undertake. I warmly thank him for

his kindness, and at my request he gives me, with a

slight Italian accent, the following information on

the maritime communications of Fu-san with the

neighboring countries. There are only two services

regularly established: one Chinese, the other

Japanese; the first begins here, follows the coast

of the peninsula, calls at Tchemoulpo, then Chefoo,

from where people can travel on to Tien-tsin or

Shanghai. This route passes through all the cities I

have already visited; I therefore renounce it in

favor of the second line, which from Nagasaki stops

successively at Fu-san, Gen-san and Vladivostok,

thus allowing me to complete my visit to Korea and

reach Siberia. I express my gratitude to Mr.

Civilini for his valuable information and, after

exchanging a few toasts to the union of our two

countries, we part, delighted to have made one

another’s acquaintance. My two small mousmes then

spread on the floor the ftons, light mattresses

between which one slides, and I soon form with them

a true human sandwich. A few moments later I enjoy

in the dark all the softness, tranquility, and charm

one experiences when feeling reborn to life after

long deprivations of all kinds.

The next day I pay visits to the

mandarins, to Mr. Civilini then to Mr. Hunt,

Commissioner of Chinese Customs, and his kind

assistant, Mr. Watson, who, thanks to a letter of

recommendation from the excellent M. Piry, of

Beijing, welcome me in the most charming way and

provide all the services in their power. They even

pay me the honor of coming to lunch together with

Mr. Civilini in my hotel. The meal is accompanied by

pleasant music played in the next room, where

several Japanese are celebrating in the company of

delightful geishas,

young people who are at the same time

poets, musicians, dancers, etc.. We greet them at

the end of the meal then I go to visit the city, or

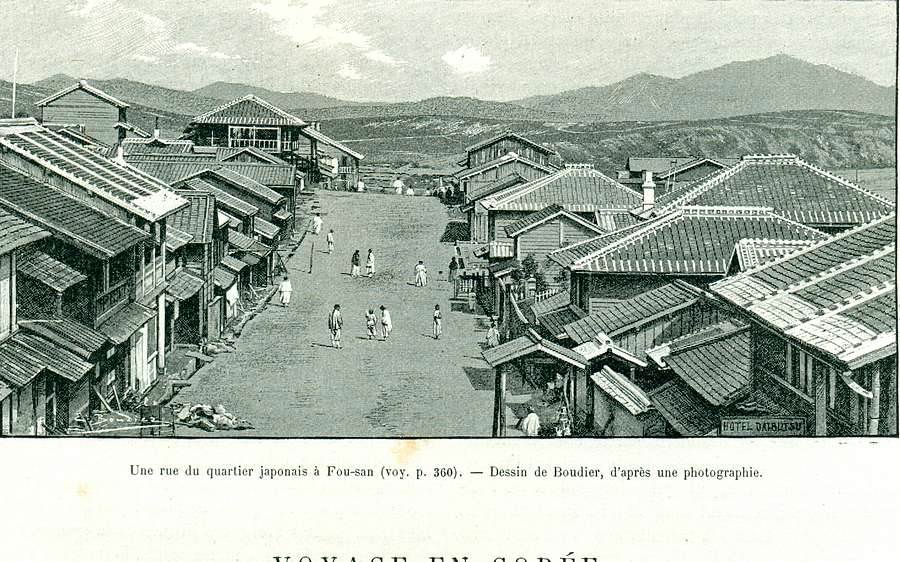

rather the European concession, because there are

actually four Fu-san: the ancient city, located

furthest to the south, and today nothing but ruins,

was a stronghold, occupied for several centuries by

the Japanese, who had made it a veritable trading

center, a warehouse for all their goods. This is

followed by the Korean Fu-san, located further to

the north and also fortified, then the European

concession, of which I will say more. This is

certainly the most important port in Korea, less

picturesque than Tchemoulpo, it nevertheless offers

magnificent views from the top of the green

mountains that frame the huge bay beautifully. The

city is dominated by the hill covered with cedars

that we bypassed the day before. At the top stands a

charming little Japanese temple lost in the foliage

that can be accessed by rustic stairways and scenic

trails. It is dedicated to the guardian deities of

the sea and a large number of votive offerings

decorate it. These represent the many shipwrecks

where Japanese sailors miraculously escaped death by

the powerful intervention of spirits or goddesses.

All these paintings, which are reminiscent of those

in some Catholic chapels, may not be masterpieces,

they are very interesting, given the sense of faith

and gratitude to the gods that the artist often

represents very truthfully, by the expression on the

faces and the attitudes of the shipwrecked mariners.

At the foot of the sacred hill extends the

concession. Recently built by the Japanese, this is

truly a city of their country, and they monopolize

the whole trade of the port. Businesses are so

successful that some dealers sometimes earn, I was

told, more than a hundred thousand francs a year.

Yet despite this, there are here, apart from the

customs employees, only two or three Europeans. What

I might call the Korean maritime Fu-san is more than

a league from the commercial port. It is reached by

a road along the coast, which from the top of a

succession of hills overlooks the sea in a most

picturesque manner. The native city, very miserable,

is partly inhabited by fishermen; their houses are

located on the Strait of Korea, and are usually

preceded by large circular holes about three meters

in diameter and one meter deep, dug in the ground

and covered with clay. Four pillars two meters high,

placed perpendicularly square around these tanks

carry a light thatched roof to protect the

sardine-fertilizer that is prepared for export in

large quantities in Japan, where it is used to

fertilize the land. The prohibition under penalty of

death to have any dealings with foreigners which

lasted for centuries prevented Korean sailors taking

to the high seas, so today most of their fisheries

are still installed on the shore. Huge wooden fences

are erected, with a single entrance, toward which

the fishing boats push the frightened fish, then

they close the opening and take all the prisoners.

On returning to the hotel, I learn that

the Takachiho

Maru on its way to Vladivostok arrived a few

hours before and will leave immediately. I hasten to

settle my account at the hotel, take my ticket and

board the ship just before her departure. MM. Hunt

and Watson, whom I found there, present me to

Captain Walter, to Poli, customs clerk, on vacation,

who will make the trip with me, and to Mr. Brageer,

of Scottish origin, on his way to Gen-san to replace

one of my compatriots, Mr. Fougerat, whose

five-yearly leave is due. A whistle sounds, I thank

once more the friends who are leaving me; they get

into their boat and we wave our handkerchiefs as

they return to land in the boat of the customs,

while we take the sea in the direction of Gen- san.

Soon night falls, the lights are lit, our steamer

glides gently on a sea without waves, the air is

warm and soft to breathe, and sitting on the deck,

we enjoy the serenity of this beautiful evening,

abandoning ourselves to the poetry of a blue sky

full of millions of stars, then Captain Walter

graciously invites us to take a cocktail with him.

We go to his cabin and enjoy a few pleasant hours,

for the commander is as amiable as he is jovial, and

my two companions are in no way inferior. Thus,

after finding myself for so long away from any

European, this trip is a true festival for me. The

next morning I visit our ship: it is almost new and

beautifully equipped, the crew consists of Japanese,

excellent sailors then, so everything is for the

best. We follow the Korean coast at a short

distance, the coast being formed by a series of

hills parallel to each other and to the shore,

generally low, but very beautifully shaped. Suddenly

everything disappears, we are in fog and need to

stop soon, for fear of striking an island that

serves as a landmark for navigation. The sea is

smooth as a mirror, not the slightest breeze;

prisoners of the thick fog, it is only after sixteen

hours have passed that the wind blows at last,

clears the atmosphere, and we recover our freedom.

once our location has been identified, the ship

quickly heads for Gen-san, where we arrive late at

night; these delays in the off-season frequently

occur along the shores of Korea.

Mr. Fougerat comes aboard and takes us

to M. E. Greagh, the Commissioner of Customs, for

whom I have a letter of recommendation. He welcomes

us in the most charming way, he congratulates me on

my journey through Korea, highly approves my visit

to Siberia from an ethnographic point of view, and

even gives me serious information about Vladivostok

that was most useful there. We finish the evening

with a sort of declamation contest in French,

Italian, English, Chinese, Japanese and Korean, the

latter being preferred for its sonority in the

opinion of all, even the Chinese and Japanese

consuls come to visit the very friendly Mr. Greagh.

As I was leaving he surprised me by graciously

offering me a plan of Gen-san produced by a local

artist, as well as a piece of cloth of incomparable

finesse, brilliant and beautiful as silk. This

fabric, produced locally with some white nettle

fibers that grow in abundance, is an absolutely

national product.

The next morning, an east wind is

blowing violently, and as the harbor is not

protected against it, it is impossible to go ashore,

the rough seas sending such waves breaking on the

shore that no boat could reach land without being

broken. We must remain on board, then, and wait

patiently, taking at eight a first breakfast with

chocolate, at ten, tea with forks, then at half past

noon, the main lunch. As the storm does not calm

down, we are consoled by an afternoon tea, the main

dinner at seven o'clock, then tea; I have never

eaten so much in my life, contenting myself

throughout with my two meals as in Paris. Therefore,

after a final cocktail, when someone suggests going

to bed in order to rise early, I am the first to

give the example. The next morning the wind has

dropped, but the weather is overcast yet sometimes

brief rays of sun illuminate for a few minutes the

beautiful bay surrounded by islands with half-wooded

hills. The greatest activity prevails on board,

because we can now operate the unloading of the

goods. The captain takes us ashore in his Japanese

boat, then turning the sail, he goes with his three

beautiful dogs hunting wild duck in the neighboring

islands, which are most rustic.

Gen-san extends along the shore at the

foot of a circle of hills planted with scattered

trees. This is an absolutely Japanese city, but as

it is of very recent foundation, the houses are

scattered here and there between three small rivers,

crossed by elegant bridges that will give a lot of

character to the city when it is completed. On the

right opens the tiny harbor in masonry for the

customs boats, whose dependent buildings stand

further back, consisting of a large wooden shed to

house goods, and a pretty mandarin house where the

records are kept.

At the center of the scattered

dwellings of the Japanese settlers has been laid out

a potential garden, it having only been planted last

year. It capriciously surrounds a rock crowned with

a small decorative pagoda, from the foot of which

you can enjoy a magnificent panorama of the

surrounding landscape, limited only by the delicious

profile of the surrounding mountains with their many

green sites. On the right stands the Consulate of

Japan, in the middle of a huge walled yard where, if

attacked, the entire colony could take refuge. For

the Japanese, who know they are hated by the

Koreans, take great precautions wherever they are in

groups, justified by the massacres of which they

were the victims in Seoul after the treaties of

1882. Finally, on the slopes of the central hill,

stands the vast yamen of the governor, which is

located near the house of Mr. Greagh, whom my

companions and I visit, wishing to thank him by a

gracious invitation to dinner. Then, leaving the

concession, we head north along a road that follows

the hills across the well cultivated fields. Many

Koreans are at work there and they look to me like

living parcels, for, given the cold, they have lined

their clothes with cotton wool, giving them an

extraordinary girth. The true Korean Gen-san is

called Tok-Ouen; it extends over a length of more

than a league, and, though populous, the city has

only two long parallel streets, intersected by many

side streets and three public squares, of which the

main one, located in the center of the city, serves

as the market-place. There must be a great trade in

furs, judging by all the skins of wild animals that

I see hanging everywhere; moreover, the many shops

in front of which we pass contain goods of all

kinds, and I take the opportunity to make various

purchases. All the houses are low, but with the

peculiarity that the underground conduit in which

the fire is lit in Korea ends here in a really solid

chimney made of wood or mats. The little garden that

surrounds each property is closed in the same way:

the result is a very poor overall impression. My

companions want to visit a Korean inn which we are

passing; they emerge again immediately, exclaiming:

"But it’s horrible! How could you live there?" I try

to remove this very bad impression by saying that

the splendid hotel they have just visited is

reckoned one of the ugliest in the country, and we

walk back merrily, watching pigs trotting ahead of

us, driven by children, pigs being bred here in

large quantities. They are of two types: native and

cross-breed; the first look very much like small

wild boar, the latter are very similar to American

pigs. All of them have the ears pierced, not for

rings, but in order to pass the rope with which they

are led. It is in this unique company that we arrive

at nightfall, at the home of Mr. Greagh, where an

excellent meal awaits us, served with all the

comforts of old England and followed by the most

delightful evening. Naturally we talk about Gen-san

and the great future of this port as a result of its

geographical position, which puts it in direct

contact, by a road already busy, with Seoul, and by

sea, with Fu-san, Vladivostok and Nagasaki, its

close neighbors. I absolutely agree with these

gentlemen, because I feel sure that within a few

years Gen-san will have become a major international

center in Korea.

We then talk about the local customs,

the main products of the country, and finally the

wild game that abounds. I learn that tigers flee the

winter cold of Manchuria, head to the southeast of

Vladivostok, and descend into Korea along the Sea of

Japan, usually in pairs hunting wild

animals; when they cannot find any, pressed by

hunger, they come close to the villages, and

sometimes penetrate by night into the courtyards, as

happened shortly before we arrived to our gracious

host, whose two dogs were thus taken. The number of

big cats is so great in the peninsula, that each

year hundreds of skins are exported, besides local

consumption, which is very significant, because all

the mandarins use the fur for their official seat. I

inquired about the depredations of these beasts.

Many natives, I am assured, are daily victims, in

their property and even their person, as a result of

real carelessness such as sleeping outside their

house in the summer, or hunting alone in order to

collect all the premium and the price of the rich

fur of these animals. All of which, I tell them,

confirms my ideas about this, because for me the

tiger pressed by hunger attacks only isolated

individuals and always flees from a group of people,

unless it is attacked.

"Yet, they reply, the Prince of Wales

in India had one of his elephants attacked.

—This is further proof of what I have

just said.

Indeed, during the princely journey, to

avoid accidents, many beaters preceded the escort; a

tiger passes between them and seeing them move away,

thinks he has escaped, but then arrives the main

body of the caravan, it believes itself trapped and

defends itself, as I said earlier.

—So for you, these big cats are not at

all something to be afraid of?

—For explorers, at least, since they

are necessarily accompanied by their suite.

—I wager you will not relate that in

the story of your travels.

—I will, on the contrary; I know that

in speaking thus, I shall deprive myself of moving

stories to tell, but I shall at least have the

satisfaction of telling the truth, and rarer still,

of being believed, since by my return to France, I

shall have traveled to many countries inhabited by

these felines, including Korea, Siberia, Indo-China

and India. I would add, to convince unbelievers,

that despite all the legends, tigers have actually

rendered even more services to explorers and

especially to publishers than they have done them

wrong, because we look in vain in our annals for the

tragic end of one of us, finishing the course of his

explorations in the belly of a great beast." And everyone laughs. "For me, I continued, the extraordinary

tales of storms and the terrible hand-to-hand fights

with wild beasts that I read about long ago seem to

me to be the cause of the terror of our grandparents

and their opposition to the departure abroad of our

ardent youth, all to the detriment of family and

country, just when the struggle for life makes more

than ever necessary the rapid expansion of our

national forces." When I had finished this little

set piece each approved me. May I be as happy in

France and soon see a swarm of young travelers

setting forth, already encouraged by the military

state through which they have all passed. The

evening ended, as we walk through the fields back to

the steamer, there sounds behind us in the silence

of the night the sinister growl of a tiger, then

another; will Il finally see one? We stop, and

suddenly into our midst jumps friend X ... Who is

treating us to this little family entertainment! We

reply with a general meow of

farewell, after which, as in the song, everyone goes

to bed, some on board, and others ... at home.

Two hours later we left Korea for

Siberia, where I hoped to complete my ethnographic

studies in the north, as I had done in the East by

passing through part of Sakhalin and throughout

Japan, and finally to the West to visit China in the

north, center and south; indeed, we can only know

the ethnography of a people if we have some general

ideas about the countries around. I was delighted

with my determination, because, thanks to the kind

hospitality of M. de Bussy, state adviser to the

Russian court, and his outstanding work on the

northern countries that he studied for several

years, finally the very interesting Siberian

collection assembled by him, I saw a strange kinship

between ancient Siberian tribes, especially the

Tungusians, and Koreans. Without going into detailed

considerations, that will be developed in our

volume, we will simply say here today that this

affinity occurs in the most unexpected way; indeed,

while we encounter almost no Koreans in China and

Japan, they are counted by the thousands on the

banks of the Amur and in Vladivostok, where they

have taken complete control. A huge amount of trade

is also being done there by the Chinese, but apart

from some Russians there are very few Europeans. The

city, located at the end of a huge bay is protected

by picturesque hills covered with fir, larch, pine

and birch with their silver trunks. The fleets of

the world could take shelter in this huge harbor

that, although closed by ice for two months of the

year, is none the less called to a great future,

just as Vladivostok, whose origin is recent, is

already the queen of the north, and its prosperity

can only increase. Soon, indeed, a network of

railways connecting the Siberian lakes and rivers

crossed by steamboat, will link it in a trading

relationship not only with the entire Russian

empire, but with the whole of Europe and all of

North America. One rival to be feared is the likely

development of the new open port that Korea has

awarded uniquely to Russia on its north-eastern

border, for, being ice-free all year round, it is

expected to become the center of all the trade of

the northern world.

After a tour around Vladivostok, we

take to the sea and revisit successively Gen-san and

Fusan, where our friends welcome us heartily; when

will they allow me my turn to receive them as

happily in Paris? For the cordiality that exists

there between Europeans is really a lovely thing. As

I was leaving Korea for the second time, I thought I

had finished my local studies. Well, I had to

experience the emotions of a typhoon in its waters.

Emerging from the Bay of Fu-san by night, we find a

pretty high sea running. Friend Fougerat, who has

already had some experience of it and fearing the

appearance of new challenges, retires to his cabin

and we stay with Mr. Poli to enjoy the special

pleasure of feeling ourselves somewhat rocked by the

sea; at a sign from Captain Walter, we immediately

join him on the poop deck because from the bridge we

can see little, and up there one is at the very

center of the most wonderful sea panorama. Although

the weather is overcast, the opaque light of the

moon passes through the thin layer of clouds that

hides the sky, and all around us, the waves glow

white: it is superb. After an hour friend Poli,

feeling weary after our pleasures of the day before,

goes to bed and I am left alone with the commander.

Now the sky has become completely dark, it seems

that the light comes from the sea, which seems

illuminated by the dazzling foam of the waves. They

break noisily, growing constantly larger, as the

wind rises more and more. We are now rolling on the

waves in a terrible way: sometimes our steamer

points its sharp bow in the air, then plunges into

the sea, as if to fathom the abyss, or caught on the

side by a great wave, turns onto its side as if to

die: it is truly terrifying. Suddenly the masts

scream, a terrible crash is heard, and our ship,

pulled backward for a moment, falls with a crash

into the water at the same time as a huge wave

inundates us, but the steamer straightens itself

again on the dazzling peaks and we rule the raging

sea. Oh! Beautiful, it's beautiful! "Good sailor,”

says Captain Walter, hitting me on the shoulder.

–Thank you, sir! I owe you the best show I’ve ever

seen in my life." And, clasping our hands tightly on

the bars of the poop, we enjoy the great horror of

unbridled nature, which seems to be returning to

chaos. In vain the wind increases, the storm

redoubles and waves rush upon us in a final assault,

I am now calm and quiet, I feel that the spirit of

man is finally master of the storm, he has built the

unsinkable, leads, directs and guides it where he

will, because the will of the captain governs it

more surely than a rider pressing the sides of his

mount. At the moment when, carried away by the

triumph of mind over matter, I almost believe myself

a God, a terrible fit coughing overtakes me and here

I am, leaning breathless over the abyss. Soon a

semblance of calm appears around us, and the

Captain, touching my clothes soaked with water, says

we should go down, and as the mate is taking charge,

we go down together. Walking is really difficult,

because with pitching mixed with rolling in order to

advance we must wait for a movement of the steamer

to allow our hands to grasp rope rushing at us or

some asperity if we are not to go rolling across the

bridge. Arriving in the saloon despite our perfect

instability, we prepare the incredible cocktail

which is to warm us up. That was no easy job, I must

say! That done, the captain goes back to his post,

and I, absolutely drenched because of not having

worn waterproofs, I go shivering to my cabin, change

completely and soon feel penetrated by the warmth

around me. I am hardly in bed, when I am suddenly

lifted and thrown out of my bunk, at the same time

as the creaking of the wooden vessel, the panting

engine, the sinister hiss of the propeller turning

in the air, mix suddenly with the terrible shock of

a huge wave and a loud clatter of broken crockery,

then a silence followed by a tremendous beating

sound on the deck. "Go up and see what's happened,"

Signor Poli tells me from his cabin. "All my

regrets, old chap, but I have undressed and have no

desire to be crushed by all the stuff rolling around

up there. Good night, I'm sleeping." I try to do so

despite the incredible motion of the vessel which

now I feel just as if I was on the poop with the

captain, who is struggling valiantly upstairs while,

overcome by fatigue, I fall asleep soon, in his care

and that of God. The next day, I wake up in broad

daylight, get dressed quickly and cross the saloon,

absolutely devastated: all the dishes broken, and

two strong arms attached to the walls, which carry

the lights at the corners of the room, are lying on

the floor and I cannot explain how they were broken;

the bridge is in an indescribable disorder: two

barrels ringed with copper nearly 2 meters high, at

the back, were lifted off by the waves despite four

huge iron spurs that were joining them to the

vessel. The sea is just undulating now, as we have

passed the Goto islands, that make us safe from its

fury. I go up to join the captain; he is beaming

with a sense of duty done and holds out his hands

affectionately, saying: "Fine storm". Oh! the good

man, and how grateful I am for everything he has

allowed me to see. Our ship, damaged, soon enters

the Gulf. Although the sky is covered with ash-gray

clouds, I still admire the landscape, which is

splendid in a ray of sunshine, as indeed all the

coastal views of Japan. I will not say more of

Nagasaki than I did of Shang-Hai; the European

concession is the Paris of the Far East: both cities

are too well known. I will only say that the typhoon

we suffered had extended its ravages onto the coast,

because at our hotel, as in all the Japanese houses

on the hills, wooden fences and roofs were torn off

in part by the storm. This now earns us curious

looks from those who know that we escaped. Yet in

fact there is almost no danger on the large modern

steamers, with their admirable facilities, and the

knowledge we have now of the winds, etc.. It is,

alas! in Nagasaki that I had to separate myself from

the aimiable captain Walter and my two delightful

companions to join a ship of the Messageries

Maritimes and complete my world tour.

Some disgruntled spirits, on finishing

reading this story, will perhaps accuse me of hiding

many dangers, of having attenuated many hardships,

embellished many things. Yes, I did so, and

deliberately, because in doing so I am much closer

to the absolute truth that if I had dramatized to my

profit every least incident. While traveling through

many countries partly unexplored, two or three times

my life was in danger, but during this long journey

did those who remained in Paris run less risk? Let

them think of the flower pot that can fall on your

head, the vehicle that can knock you down on the

boulevard, the duel that the gallery requires of

you, etc. while during that time the clean air of

sea or mountain renewed my blood, new

observations illuminated my mind every day, hard

labors finally made my heart more indulgent and

tender toward all. And I would add: if true

explorations offer such advantages, how easy any

trip to countries open to all thus becomes! Are we

now going to allow only foreigners to roam through

countries where we have almost everywhere preceded

them, and give up the glorious career when recent

examples have made of exploration a craft of

princes?

It is you, mothers, I am addressing,

because the fathers are already half convinced: if

your son, after having made, depending on where he

wants to go, the absolutely essential

apprenticeship, either of the Swiss Alps, the cold

winter in St. Petersburg, or the summer heat of

Biskra, still wants to leave, if you really love

him, rather than holding him back, excite him more

in his masculine energy, and if he is respectful of

the customs and the rights of all, if he takes the

correct hygienic precautions for each climate, if he

is chaste and especially if he is sober, he will

come back stronger, more loving and more worthy.

Instead of exhaustion

by wearisome pleasures, the generous fatigues

of travel will fortify him forever; his mind will

grow by all the knowledge he has acquired, and his

heart will love you more, better feeling the

happiness of holding you in his arms. Then what joy

to find he has become someone, still full of youth,

to see him respectfully listened to by his comrades,

and not only them, but by mature men and even old

folk, happy to hear from his mouth while he saw,

learned, brought back for himself, for his family,

for the country!

Thus our fathers returned from their

heroic expeditions, where everywhere they made

France known, admired, loved, thus increasing her

influence, wealth and greatness.

Charles VARAT.