Voyage en Corée

4. (Voyage in Corea Section 4)

by

Charles

Varat

Explorer

charged with an ethnographic mission by the

minister of Public Instruction

1888-1889

— previously unpublished text and pictures

Le Tour du Monde, LXIII, 1892

Premier Semestre. Paris : Librairie Hachette et

Cie.

Ascent of the

peak of the central chain. - Great Wall and fortified

gate. - Currency Exchange. - Descent of Song-na-san,

- A stronghold. - The brigands. - Purely scientific

exploration and military expedition. - Coton. -

Peddlers. Scholar’s pole. – As the crow flies. -

Rivers. - Fishing. - Childish anthropology. - Poultry.

- Camp showman. – Half dead. - Memorials. - A suburban

inn. - Taikou. - Reception of the Governor. - The

City. - A Korean feast. - The departure. - Singular

effect of trumpets. - To Chiang. - The wild flower

shines in my buttonhole! - Rain. - Mil-yang

architecture.

After two days

climbing through the foothills of the central chain,

we finally reach the crossroads of the cross, the

King-pang-cha-nadri, a village at the base of the last

climb up the Song-na-san. There I was told we would

have to unload the horses and hire men to carry our

luggage on their backs, as the last peak is difficult

to pass because of the steep slopes and the dreadful

rocks that cover them. I resisted this, the first

disruption of our caravan. But my interpreter provided

alarming information about this pass: never, he

assured me, had a Mandarin crossed here except by

palanquin, and if I made the journey on foot, I would

lose a large part of my prestige in the eyes of my

men, while also depriving of compensation the

villagers, whose only resource, so to speak, this is.

I am obliged

to ride in a sedan chair borne by some very rustic

porters; ten men raise it, and we begin the ascent.

Just as we set off, I understand the insistence of Ni,

seeing him likewise installed in a palanquin. His

dream since the beginning of the journey is finally

realized. But I must admit that we have never had such

a terrible road. I sit at first in European style,

allowing my legs to hang out of the chair, but I am

soon obliged to draw them in and cross them in Korean

style, so that they are not hurt by the many rocks

over which my porters carry me quickly. They

themselves avoid the higher rocks that threaten with

their asperities, emerging in forms as bizarre as

dangerous. Those carrying me are most unhappy,

groaning and dripping with sweat, even though they are

replaced every five minutes by other men. This

continues almost to the top, where the appearance of

the torrent of rocks gradually changes, their number

decreases, a few scattered trees appear; soon these

become more numerous, they begin to afford shelter by

their shade, and the ground finally levels out. I jump

out of my palanquin, upset by all the trouble I have

given, but I laugh at my poor Ni, forced to climb down

when he sees me standing on the ground, although he

would much have preferred to continue the journey in

his chair. As we climb on, the landscape becomes more

charming and the flora changes completely. Firs,

larches disappear to make room for the wonderful

woodland vegetation of Japan. We are in the autumn, I

have never seen nature adorned with such rich colors,

from dark green to golden yellow, a mixture of colors

of the happiest effect. Thus we reach the border gate

of Moun-kiang, which is topped with a pavilion

decorated with paintings, and is fortified with a

Chinese-style long wall, following capriciously the

crest of Song-san-na, which once separated two

powerful kingdoms, that now remain as provinces in

today’s Korea. There we find an inn where we must

change our currency, because it has not the same value

on the other side of the central chain. For 1,350

coppers from Seoul they offer to give me 650 in Taikou

coins. I wonder at this huge difference, but I am told

that living expenses are lower by a half on this side

of the mountain. A strange fact: I leave behind our

Korean coins and am given Chinese cash instead, having

the same shape and differing from each other only by

their larger size and their inscriptions. My

interpreter, who is also my finance minister, operates

this exchange, while our horses and men arrive one by

one, puffing, lame, and tired. I allow all the

climbers to refresh themselves; two hours later, we

replace the packs on our animals and the caravan

reforms. If the climb was difficult, the lovely

descent on the other side of the divide is more

beautiful still, after the beautiful forest that I

described earlier.

Everywhere

ancient trees, especially cedars, extend above our

heads their thick branches, between which the daylight

passes softened and bronzed, giving everything a kind

of mysterious aspect. The silence of the forest is

broken only by the cry of some startled bird or the

sound made by a fawn running away through the leaves

at my approach. I walk down and up the slopes alone,

ahead of the weary caravan, intoxicated by the

exquisite scent of the forest, enjoying the infinite

charm of solitude to the full in this ancient forest

full of freshness. I reach a gullied slope from which

rises on my right a high limestone wall; I admire the

gigantic foundations out of which the cliff rises

vertically in admirable purity, only bristling here

and there with a few brightly colored shrubs clinging

to cracks produced by rain or lightning.

I soon arrive at

a large space surrounded by crenellated walls, home of

some old lord, or rather a borderland fortified city.

Long abandoned and in ruins today, it remains a superb

architectural skeleton. We descend again, and the sky

is blue, the air warmer, with more varied flora, as on

this side of the mountain warm breezes arrive directly

from the Pacific. Then we are soon in a small chain of

hills, very barren and sandy in appearance, and

conical. We leave them to the right and left; they are

called Ching-Chang-tong or “mountains of thieves.”

They are now a haven for bandits who have taken

advantage of the famine and are beginning to organize

themselves into bands. Following the middle of the

valley, which is increasingly well cultivated, we come

at nightfall to the small town of Ma-pouang where we

are to sleep. When making my evening meal, I hear far

away, sung by powerful voices, some kind of Korean

anthem of a challenging, warrior character. Soon the

chorus approaches, then stops, only to start again at

the very door of the inn. I go out and see, to my

surprise, all the singers armed to the teeth. Some of

the inhabitants of the locality, I am told, meet fully

armed and sing all night long to warn the bandits who

are ransacking the region that the village is on

standby and they are ready to defend themselves. In

spite of the fatigues of the day, I do not sleep well,

woken a hundred times by this lugubrious chant

accompanied by drums and cymbals; it is the same every

night following, as a result of the terror the bandits

inspire. Yet, strange to say, we soon get used to this

nightly concert and continue our journey without

worrying about a state of things which we can do

nothing about, a caravan being only attacked by bands

more fully armed or ten times greater in number. So

all my defensive system lies in the speed of our

movements, since I count on the surprise caused by our

unexpected arrival and rapid departure, before they

can plan anything against us. These are, I believe,

the best conditions for success when travelling

through an unknown country. The scientific explorer,

messenger of peace and progress, should only bear arms

openly in a country where, since everyone has them,

their absence would result in a real inferiority in

the eyes of all. In all other cases, a visible arsenal

is a provocation. These are the mehods I have used

everywhere and I have always found they work

admirably. As you see, dear reader, it is really quite

elementary.

Naturally, I

am not talking about military explorations, they have

all the advantages but also the dangers of war. How

many of us have succumbed! To cite only the latest

victim, I call to mind the unfortunate Crampel, whose

unexpected death has painfully struck the heart of

all. Alas! why is it that I, who loved him so much,

must throw from so far away a few flowers on his

neglected grave, recalling what a cruel loss for

France this energetic man was, so distinguished in

mind and so delicate of heart! Yet of him and all

those who have died as martyrs of science I will say:

mourn them, console their loved ones, but do not pity

them, because it is beautiful to die for the progress

of humanity.

Since we left

the central chain and began heading towards Taikou,

the capital of Kyeng-to-Syang, by way of Sai-Ouen,

Oul-mori, Poul-tcheouen before entering the valley of

Yong-san-tong, the landscape has much changed and now

vast fields of cotton extend on all sides around us.

Unfortunately it has all been harvested and there

remain on the harvested bushes only a few forgotten

scraps, speckling the plain with their snowy

whiteness, glittering in the sunlight in their

multiple isolation. Everything in the picture is

exquisite, for the weather is wonderful and I know few

countries where the air is purer, more transparent,

more luminous than in Korea. We no longer see women

engaged in harvesting barley or rice: they are busy

with the various operations that cotton is subjected

to before being turned into cloth. The road is alive

with many Koreans bearing on their backs heavy bales

of cotton. These porters, by whom all transportation

is done, because of the poor state of the roads, form

a vast brotherhood, they are administered and judged

by themselves and so escape from the jurisdiction of

the mandarins; if the latter bother them, they

immediately leave for another region: this is their

way of going on strike, and they are soon recalled,

given the impossibility of life without them.

All this is

highly consistent with the broad associations known as

artèles,

that we frequently encountered in Siberia and northern

Russia. It is sometimes said that they have poor

morals, but I think the opposite is true, for the

womenfolk among these peddlers are highly respected,

they punish adultery with death, they are very robust,

hard-working and merry, stand back in respect at the

passage of any Mandarin or Official, and are essential

intermediaries of all trade within Korea, enjoying a

reputation for high integrity. The more I advance in

the country, the more I find myself loving the people,

they are so brave, so industrious, so honest, and at

the same time endowed with all the family virtues. As

we passed through Sol-pay-ky, Pou-chay-Dangy, Tol-ki,

Yetchon, Tol-Ouen, Kain-mal and Ko-chi, sometimes we

found at the entrance of the small towns, a pole ten

meters tall topped by a huge, oddly colored dragon of

wood, which from far off seems to be flying in the

air. To prevent the wind blowing them over, four ropes

descend from the top of the pole and are fixed in the

ground, where they form equal angles. Residents erect

this singular trophy at the entrance to their township

when they have the honor of having among their

citizens a scholar of the first class. The common

people have such confidence in the lights of those who

have passed their exams that I saw, during a

discussion in the field, Koreans take a simple scholar

as referee for their quarrel and submit to his

judgment. This shows the high esteem in which

instruction is held in Korea, where almost everyone

knows how to write, and what rapid progress people

will make once they are aware of our European

sciences. We enter the valley of Haing-tong, heading

toward Han-king-kepy.

Often in

villages my gaze fell on a beam from which was

suspended a huge wicker basket, 3 meters long, in the

shape of a cigar, with in the middle an opening, in

which the hens come to seek refuge against the many

foxes that are not at all frightened by the beautiful

tail, more than one meter long, of the Korean cock or

the two huge white discs, like wafers, that the hens

have around their eyes and give them a family

resemblance to their sisters in Cochin. The exquisite

flesh of these birds often replaced other kinds of

meat for me, their eggs have complemented many times

my usual meals.

The road

leading us to Taikou is still long: therefore, fearing

to abuse the reader's patience, we will move as the

crow flies, that will be even better since we have to

pass not only the Nak-tong-kang, but some of its

tributaries, the names of which, however, are almost

as unknown as those of the places we are going to pass

through.

We enter the

Haing-tong valley and cross a tributary of the

Nak-tong-kang, the Tong-kang-tchou, flowing quiet and

peaceful. Here and there we find some noble but poor

Koreans indulging in the pleasures of fishing, which

they enjoy in a quite special way.

All the fish

they catch are immediately stripped of their scales,

immersed still alive in an excellent soy sauce and

eaten raw by the fisherman, who continues

philosophically for hours his fishing and his lunch.

In the Far East

the fish are exquisite; I myself have eaten some in

Japan, and the pleasant memory still delights my

palate.

We then

continue by way of Smo-tang, Oung-Ouen-y, Tol-Kokai,

Chon-Ouen, Hai-ping, Thai Chiang, Chang-nai, Savane,

Mal-sai-chang-chang, where we cross a second tributary

of the Nak-tong-kang, the Tong-kang-soul, which, like

all rivers and streams in Korea, is not navigable,

owing to the lack of depth and very dangerous rocks

creating impassable rapids. Therefore navigation with

freight does not exist: only small boats engage in

fishing by frightening the fish and forcing them to

flee into nets prepared in advance. River fishing,

excellent and abundant, feeds a large portion of the

Korean people, who mainly eat fish, either fresh, dry

or preserved in some other way. Then we reach a third

tributary of the Nak-tong-kang, the Tong-kang-kol;

this river, like almost all the rivers and streams of

Korea freezes completely in winter. To engage in

fishing, they make holes in the ice, surround them

partly with nets, then, running and hitting

everywhere, they drive the frightened fish into the

nets. The ice is always of a great thickness, the

maximum of heat or cold are about +35° to -35°.

Therefore, in Korea, especially in the north, sleighs

and snow-shoes are used during the winter, and the

Koreans are very proud because they owe to them one of

their great victories over the Chinese. We leave the

river and go on through Ka-chang-mou, where, after

crossing the hills of Kong-tek-y, Song-tong, and of

Tchin-san, we finally return to the Nak-tong-kang.

The river

stretches before us, about 400 meters wide, but not

deep. We proceed to cross, loading our horses and our

luggage onto boats under the eyes of a crowd of naked

children curiously following developments. I take some

anthropological notes, which I will summarize here

briefly: all these boys and girls are slender and

beautifully proportioned. Brachycephalic head, medium

sized, slightly raised supported by a very elegant

back and neck, the hair, very dark brown, has a red

tinge, the eyes are black and shiny, sparkling with

gaiety, the nose and chin are small, likewise hands

and feet, including wrists and ankles of a rare

distinction, arms and legs are exquisitely

proportioned, the body is beautifully arched, the

chest projecting forward and the small of the back

very graceful curved. The build of all these small

bodies is of a rare aesthetic perfection, especially

there is a little girl about ten years old whose body,

warmly colored by the sun, appears to be a miniature

version of the Diana

by Houdon.

This

anthropological study of the children seems to me to

establish that the children, like the majority of the

middle classes, approach exactly the Tungusic type,

very different, as I will show in my book, from the

type of the higher social classes and that, no less

characteristic, of the lower classes.

After crossing

the river safely, we continue on our way and soon

reach a series of hills rising steeply on either side

of the river, which we follow mid-way up the slope.

Sometimes the river rolls at our feet calm and quiet,

sometimes it breaks tumultuously through rocks

detached from the hillsides. Night comes, and it is

lit by torches that we follow the narrow path, where

the slightest misstep would precipitate us into the

river. Fortunately, after an hour of this perilous

journey we finally leave the Mak-tong-kang to regain

the plain and under a shower of sparks we reach the

village where we spend the night.

The next day

and the following days, we pass successively through

Morai-tong-y, Tong-hai, Chang-na-y, Nam-chang-mo-ran,

De-nai and Kam-tong, along a valley which leads us to

Ho-kong-nai and Sam-thang then Mam-tong, where we

continue over a plain bounded by the hills that I have

already described, finally reaching the city of Hiran,

where we see a large number of small sheds in wood, a

cubic meter in size, thatched and supported by a pole

two meters high. A multitude of small primitive stoves

are dug in the earth for the use of rural folk, who,

attracted to this place by a monthly market, can not,

because of their large number, all find lodging with

their neighbors and brothers in the Korean family

whose father is the king.

As we are

advancing slowly because of our previous fatigues, I

send one of my soldiers and a groom ahead of the

caravan to bring my card to the Taikou governor,

asking him to let us enter the city after the closing

of the gates if we are late.

Alas! An hour

later, we find our soldier with his clothes torn, his

companion lying on the ground, seemingly dead, and

some Koreans gathered around him trying to revive him.

Here is what happened: the groom, being inebriated

refused to obey the soldier and they began fighting

there, and our man, knowing the severe punishment that

his revolt against the army deserved, was now feigning

death to escape. I take his pulse, and as I find

nothing wrong, I immediately order the caravan to move

ahead, to general approval, noting once again how

readily legal authority is respected Korea. What am I

saying? it is everywhere honored, as evidenced by the

many monuments erected by the people at the entrance

of towns and villages in honor of mandarins who have

distinguished themselves through their virtuous

administration.

Some are small

monuments, with roofs and powerful buttresses, forming

a small open chapel, others are simple headstones in

cast iron 60 centimeters high by 20, with raised

characters. Many of them are very old and show the

high degree to which at one time the metal arts had

developed in Korea: this is likewise shown by the

ruins of iron towers of which the Chinese ambassador

speaks in the narrative of his journey through Korea,

dating from so many years before the Eiffel Tower.

We are

increasingly delayed as a result of our unfortunate

incident, and after crossing the Kornou-kan, a

tributary of the Nak-tong-kang, night surprises us,

and since the governor had not been contacted, we find

Taikou closed. We must spend the night at the very

gates of the city, in a miserable suburban inn. My

room is the most horrible I have ever inhabited; a

mere detail, the ceiling beams are completely

invisible behind a thick covering of cobwebs. When I

propose to make it disappear, I am very strongly

opposed and I finally prefer to leave the brown

weavers quiet, rather than expose myself to their

vengeance. Nobody insists, because all my men are worn

out with fatigue. As for the horses, they are so weary

that once they arrive, for the first time ever they

refuse all food and collapse as if about to die. I

find them the next morning still in the same state of

prostration, and my companions too; for both it was a

painful journey, especially crossing the mountains,

although they were not 3000 meters high. I allow

everyone to stay lying down the whole day and send my

official card to the governor. He immediately sends an

honor guard and a letter, apologizing for not having

opened the gates at night; he invites me to a solemn

reception during the day, tells me he has prepared for

me apartments in the yamen, and offers me hospitality.

I immediately write by my interpreter thanking His

Excellency for his kind attention, and saying I will

be honored to accept his gracious invitation to go and

offer my respects. I sign the letter, send it off, and

quickly extract from my suitcase my evening dress.

Alas! coat, waistcoat, trousers, following various

soakings, have taken the most unexpected shapes; yet I

absolutely must wear them, since the governor has

attended official receptions of Europeans in Seoul as

Minister. I therefore hasten to dress and inspect my

costume using a mirror the size of my hand and see

with distress that the legs of my trousers and the

sleeves of my coat are like corkscrews, while the

tails of my dress coat are fleeing from one another

like two irreconcilable enemies, but fortunately my

cuffs and my celluloid shirt front are shiny bright. I

count on them absolutely to save the situation, and

leave my room, head held high, my folding top hat

under my arm. At the sight of my strange black suit

two hundred people manifest signs of stupefaction,

which suddenly changes into awe when I suddenly open

my hat with a clack to shelter me from the sun, but

once I have it on head a general murmur of admiration

is heard. Because although Korea has hundreds of

modelsof hats, pf different materials and shapes,

never, never, had anything been imagined similar to

mine. O Gibus! sleep happy. . . I hasten to escape

from public admiration by sitting down inside my

official palanquin; eight strong men lift it

immediately, and, preceded by my two soldiers,

followed by my servants, surrounded by the escort of

the Governor, I am soon in Taikou, where no European

has yet penetrated. Great curiosity followed me along

my way, but without the slightest sign of hostility.

We thus arrive at the yamen at the same time as a

local mandarin emerges with his retinue, whose

guttural cry opens a passage for him through the

crowds. I enter the first chamber of the palace,

gladly climb down from my palanquin, where my crossed

legs are in agony, and enter the palace. I am

ceremoniously led to the state room, a reduced model

of the palace in Seoul .

The governor,

sitting on his throne, surrounded by his brilliant

court, rises as I approach. I salute him in European

style, he does the same, and after the usual

compliments, when we repeat what we said in our

letters, His Excellency invites me to sit on large

cushions and enjoy a collation with him.

No sooner have

we taken place that each of us is brought four small

tables crowded with the strangest dishes. They are

served in elegant porcelain vases, much larger than

those used in China and Japan. I do not fail to rave

like a true oriental about the beauty of the service,

the perfect seasoning for the meat and fish, so

deliciously dressed, and then praise the pastries,

sweets, fruit and especially the delicious rice wine,

with which I drink a toast to His Majesty the King and

to Korea. The governor replies with a toast to France.

And as the rice wine really is exquisite, I ventured

to offer another toast to His Excellency and to the

province where he has become a truly revered father.

He in turn drinks to the health of his guest and

wishes me a happy trip. The collation once finished,

there follows a conversation between us. My

interpreter, translating each of our successive

sentences, first tells the Governor how very touched I

am by the high courtesy with which he has deigned to

receive me. He says he is pleased to welcome as a man

of high science, appointed by the French Government,

and congratulates me on my journey which, despite the

present circumstances, I have dared to undertake, the

first European to do so.

Humble thanks

follow on my part, after which I explained how I was

struck by the friendliness of the inhabitants of the

kingdom, its rustic beauty and especially the splendid

agricultural development, which, when it comes to

irrigation sets Korea at the head of all the peoples

of Asia.

“Unfortunately

the weather was against us this year, and despite our

efforts we have, as you saw, the beginnings of a

famine.”

—The day that

Your Excellency wishes, you will, as in Europe, be

able to avert this scourge.

A

great clamor of astonishment rises among the three

hundred people who comprise the governor’s suite.

“Have you no

famine in Europe?

—We had in

ancient times, but now we are sure to escape.

A new movement

of surprise among those listening.

“Do you have

such power over the sun and the clouds of heaven, and

the winds that blow?”

—Alas! No,

Excellency, but famine cannot extend everywhere at

once, and the speed of our transportation allows us to

inexpensively bring the abundant harvest of distant

countries where it is needed.

—I know that you

have immense palanquins driven by steam, carrying

everything very quickly, but as you were passing

through our terrible mountains, you had a chance to

judge the impossibility for us to build similar

vehicles here.

And the entire

audience expressed its approval by flattering murmurs.

“I apologize to

your Excellency but I do not share your opinion,

because the many obstacles which you mention will

easily be overcome the day we charge our French

engineers to perform the necessary work.”

Amazement.

“What! the thing

is possible?”

—Very easy, and

if your revered king and father is willing, we will

soon cross the country in a few hours, passing, as he

wishes, either above or below the mountains.”

Exclamations of

admiration from all who surround me.

“But I will not

deny it would be much cheaper to go over rather than

under them.”

General

approval.

“We will look

all examine the matter, because we know that in Europe

you are the masters of science.

“But you can

also acquire the same skills.”

And as everyone

smiled doubtfully:

“Do as Japan

does, Excellency; send us the elite of your brilliant

youth, and soon they will spread here all those

sciences that you know of, helping to strengthen the

ties of friendship recently contracted between our two

countries” .

And the

governor, who seems delighted, absolutely wants me to

stay at the yamen, and puts several rooms at my

disposal. I appologize that I am unable to accept his

offer, eager as I am to leave the next day, and not

wanting to cause such trouble in his palace. He

insists, I continue to thank him a thousand times for

his generous hospitality; then His Excellency rises,

the audience is over. When I go back in my palanquin,

my escort of honor is doubled. I have become at least

Mandarin first class!

In this

pompous procession we make a long tour through the

inner city, and I will describe the view from the top

of the walls. My palanquin follows the path round the

walls, which remind me very much, though smaller in

proportions, of the walls of Beijing.

The walls form

a vast paved parallelogram surrounding the city. In

the middle of each side rises a magnificent fortified

gate, surmounted by an elegant pavilion. Each is

decorated inside with many paintings and inscriptions

recalling past events. From there I admire the

Kornou-kan winding through beautiful countryside, the

strongly colored russet tones of autumn in the

distance, and all around us unfolds a half-circle of

hills melting into a blue sky, lit by the rays of a

bright sun whose warmth contrasts pleasantly with the

bitter cold we endured in the central chain of hills.

At my feet lies

the great city with its streets, squares and

monuments; in the popular neighborhoods the houses are

thatched, but in the center of the city, home to the

aristocracy, rise elegant roofs whose tiles and ridges

form a blend of straight lines and curves of a

beautiful harmony. We admire in the same style two

temples, a large school for the study of the Chinese

language, and finally the yamen, completely walled,

which contains multiple buildings among which the

reception hall exceeds all others with its broad

polychrome roof, from which emerges a mast with at its

top the huge red banner of the governor, floating in

the air overlooking the city.

Such is Taikou.

Back at hotel Spiders, I find a delegate sent byHis

Excellency asking me again in his name to go and stay

at the yamen. I send a letter of apology, and avoid,

wrongly perhaps, all the demands of Korean étiquette

in order to live in my own way after so many fatigues.

The same evening I receive many gifts sent by the

Governor: chickens, eggs, pastries, candies, khaki,

etc.. A new thank-you card, which is answered by one

wishing me goodnight. After addressing the same vows I

can finally think of my horses, about which I am very

concerned. To my delight, I find all our horses

standing up, chewing in the most joyous way the famous

hot bean soup.

We will be able

to leave the next morning early, because my servants,

who have grown attached to me, now say they are

willing to accompany me all the way to Fousan. I then

review my guard of honor, who are stationeded in full

costume in the courtyard, at the gate, everywhere, and

then reture to my room, quite delighted with my stay

in Taikou.

I confess that

if the Seoul court were not in mourning, I would,

notwithstanding the obligations of the court, have

accepted the hospitality of the governor, to enjoy all

the festivities he would probably have offered in

ordinary times. They usually consist of a concert of

Korean music, acrobatic exercises, dances performed by

young girls and women specially trained for the task,

finally a theatrical performance. Not to deprive the

reader of all these distractions, I will give here a

few sketches complemented by the amusing story of a

party of this kind roughly translated into French from

a very interesting volume about the city of Seoul,

published by Ticknor and Company in Boston under the

title of Choson,

the Land of the Morning Calm, by Mr. Percival

Lowell, secretary of the legation of the United States

in Korea.

The very witty

author says that during his stay in Seoul, he

organized a picnic with several European colleagues at

the nearest temple in order to hold a little party in

the style of high-class Koreans.

“We leave early

in the morning, accompanied by servants responsible

for everything we need to live in European style, some

geishas, Korean musicians and actors, to say nothing

of the horses needed for the expedition. We happily

cross a part of the lovely countryside around Seoul

and make the ascent of the mountain where the

monastery lies. It contains, in addition to

substantial outbuildings, two unremarkable pagodas. At

the time of our arrival the bells are being rung in

the Chinese way, that is to say by letting the hammer

fall hard on the motionless bell. Finally, three

widely spaced strokes indicate that the service will

soon start in the temples.

“We enter the

main hall, which contains images, drums, artificial

flowers, strange incense sticks and a huge wooden fish

hanging from the ceiling. When we enter, twelve monks

dressed in solemn robes march in procession in an

endless spiral, and singing while a novice crouched

near the altar beats the drum. The litany is in

Sanskrit, a language that these poor monks do not

understand, which excuses their smiles when they pass

near us. The ceremony ends soon with the usual

offering at the altar of rice, fruit and finally the

lotus flower. We go out to the refectory, where we

have dinner served by friendly geishas who, like

gazelles, have gradually grown tame. Blatant Iris even

whispers softly in my ear a few Japanese words she

knows under the impression,touching but mistaken, that

they are the language of the heart. Such charming

coquetry forms a contrast with the figures of the

monks, who are watching with amazement and say

nothing. She is really charming, this girl: I have

already forgetten in her smile that I am a stranger

and two thousand miles from my home when we are

invited after dinner to leave our seats to make room

for the performance. In an instant we were moved to

the end of the large room on mats, cushions, etc.; in

front of us, musicians are set in a circle and prepare

their instruments, and later they will be playing

other roles, thus combining two professions. A dense

crowd gathers around them, like a sea of human faces,

each of which expresses emotion, curiosity,

anticipation and contentment. Others stand along the

walls because the room is filled and even the doorways

are packed with curious spectators. They are strangely

lit by three large polychrome lanterns casting their

rays through an atmosphere charged with tobacco smoke,

giving a special color to the odd sight. At the back

of the room, the Buddhist monks with their heads

shaved, their brown cassocks, their belts of hemp,

their rosaries placed around the neck or hung from

their belts etc., look on with amazement and close

attention. Young novices, their faces shining in

admiration, contemplate the scene eagerly, forgetting

who they are and where they are. Our own servants are

mingled with them their clothes in various shades and

black felt hats are a strange contrast with the simple

garb of the monks. In this compact, varied crowd,

curiosity makes everyone forget rank: none would give

place to any other, not the servants, who in Korea

always have the privilege of seeing everything, and

not these great monks, who, despite their profession,

are keen to attend the show.

“It finally

starts. We have first the performers of music, they

draw from their instruments the most discordant

sounds, harmony does not exist whistles, flutes and

violins with two strings only agree in that they play

against the rhythm and only drums, cymbals and gongs,

because of their neutral tone, are in harmony with

everyone else.

“The concert

over, we are served tea, then comes the dramatic

rcprésentation.

“The theater in

Korea is composed entirely of single scenes. They are

almost always a monologue delivered by a single actor,

although one or two others may sometimes lend their

assistance, but they are shadows serving to better

highlight the star. There is no stage, no scenery: the

actor is in front of us with whatever costume he could

improvise to meet his needs: a little more or a little

less clothing, that's all. He skillfully captures some

features of Korean customs or usages and presents very

well their comic aspects; foreigners and natives are

all delighted. For example, here is a peasant trying

to get an interview with a noble to submit a

long-overdue request. He employs every artifice to

persuade the guard to let him, in a mixture of

impudence and blarney capable of moving everyone

except a guard dog. Finally the Cerberus is persuaded

and the rustic is now in the presence of the great

man. He suddenly becomes as respectful as you would

wish. Simple but eloquent, a model of perfect

subservience, he is obviously a man who knows what he

wants and how to get it. All this is represented by

the artist without any accessories, he does not even

have the imagined nobleman before him to whom he

speaks, everything thus relies on his talent.

“We have before

us a most remarkable artist, Here he plays a false

blind man, trying, under that disguise, to walk

through Seoul by night despite the curfew. The patrol

arrives and is deceived by all the blunders of his

pretended blindness, to the delight of the audience,

including some who have themselves sometimes

benefitted from playing the role of the clear-seeing

blind. Now comes the tragedy. A solitary traveler in

the mountains is brought face to face with a tiger.

Terrified, his mimicry gives us goosebumps and when he

suddenly becomes the tiger, emits hoarse and terrible

meowing, our blood freezes in our veins, we all

instinctively shudder. The show ends happily with the

embarrassment of a tobacconist who forms perhaps the

best part of the show. The poor devil tries

desperately to sell his goods and fails every time; he

has almost convinced someone against their own will,

when misunderstanding occurs, and finally here he is

involved in a quarrel, gets rather beaten up, then

rubbing his bruised limbs, he sits there wretched as

he raises again his inimitable cry: “Tobacco for

sale!” between each very comical scene. So, as we

return to our cells, we all repeat with the voice and

automatic gesture of the artist: “Tobacco, tobacco for

sale!” (nb. this

text is rather shorter than that in Lowell’s book)

The next day

begins with exchanges with the governor of multiple

cards, where we send each other according to the rites

a host of morning greetings. I finally sent him a

farewell letter expressing my thanks for his gracious

hospitality. In turn, he wishes me a good journey,

puts at my disposal a magnificent escort and tells me

that my lunch is prepared by him at the next stop. One

cannot be kinder, and while very thankful for princely

kindness of His Excellency, I attribute less to myself

than to France his desire to honor her modest

scientific representative. But regarding the exquisite

politeness of Koreans, I should add that the amiable

Governor and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, in

response to the souvenirs that I sent them from Paris

in return for the services they had rendered, both

sent me with perfect grace very pretty and charming

letters. Here is the translation of one of them, a

very curious specimen of the Korean epistolary style.

“Reply of Kim

Chin-Kiang, Governor of the province of Kyeung Sang,

to Mr. Collin Plancy, 4th day of the second

month of the year Keuctchouk (26 December 1889).

“Last year, Mr.

Varat, who was accomplishing his journey around the

world, did me the honor of passing through my city; we

talked long together and became friends during our

first interview and this visit caused me so much

pleasure that I have not forgotten it to this day.

“Now the amiable

explorer has sent me a present of two carpets: this

gift comes from his heart, and is so precious to me

that I can not help but have it continuously under my

eyes.

“Politeness

requires that benefit be returned for benefit: I have

therefore chosen four very fine bamboo blinds that I

am happy to send Mr. Varat.

“I hope that

Your Excellency will send these items to the recipient

and transmit to him the expression of my gratitude.

“(I conclude

this letter) also thanking Your Excellency for the

compliments that you have sent me and the praises with

which you gratified me.”

Alas! I regret

to report that the next year, I learned not only of

the death of this amiable governor, but also that of

Bishop White and the sister from Senegal who so

graciously welcomed me in Seoul.

I resume my

travelling clothes, and this time set myself at the

head of the column, that is to say the place

determined by official rites, because I now have a

more solemn procession. A hundred servants of the

Governor accompany me in their brilliant costumes,

which are of the richest silk, bright blue, pink or

green, covered with black gauze or white. All that

shines in the gay morning sun and our ponies are

distraught amid all the luxurious clothing in rich

colors, which their eyes are not accustomed to. So we

cross the city majestically in the midst of large

crowds that flock from all parts to witness our

departure. We win the battle, and a few kilometers

later, as we descend a hill in this beautiful order, a

fanfare suddenly rings out in the air, a terrible

cacophony, so unexpected, strident and fantastic that

it sounds like the last judgment. Our horses rear up,

terrified, my four horsemen fall, and one of them, his

foot unfortunately caught in the stirrup, is pulled

along by his mount. A general confusion occurs in my

valiant escort. I spur my horse to catch up with my

soldier in distress, and when I lean down to help him

my saddle turns, and I am on the ground in my turn,

proving once again how near the Tarpeian rock is to

the Capitol. I am not hurt, get up immediately,

shouting and make a sign to my people to calm the

panicked ponies, they finally master them and I am

glad that nobody is injured. So, to overcome my loss

of dignity caused by my fall, I put my arm between the

strap and the horse's belly to show them all that the

groom, amazed byour brilliant procession, had

forgotten to strap tight my saddle. After

administering the obligatory scolding, to restore my

prestige completely, I let my pony see me, and at the

sight of my costume, which he can not get used to, he

rears up on his hind legs, and wants to start all over

again, but in vain, because this time I am firmly set

in the saddle. The Koreans are very poor riders,

especially official figures, who never mount on

horseback unless accompanied by four grooms each

holding a long strap attached to the jaws and tail of

the animal, with which they direct or stop it at the

slightest movement. A mounted Mandarin therefore can

bask comfortably in the sweetest peace.

The caravan

reform, and my interpreter asked me whether to ban the

fanfares.

“Are they

usual?”

Yes, I was told.

—Tell the

trumpeteers, instead of standing at the rear of the

caravan, to go on ahead and play according to the

rites. “

Indeed, now

there is nothing to fear since the trumpets, the cause

of our accident, consist of three parts that stand out

from each other, reaching 1.2 meters in length at

their full development, so with them placed before us,

we have time, on seeing them lifted, to tighten the

reins and keep our horses under firm control. We thus

arrive with all the pomp and harmony desirable at the

village where we enjoy the wonderful lunch of His

Excellency, then my fine escort receives a final card

addressed to the governor and turns back, thanking me

for my generosity, to return by the evening to the

yarnen.

We now resume

our usual order of march in the direction of the

south-east through a landscape similar to what I

described before reaching Taikou.

We meet on the

way a young orphan of a dozen years old, absolutely

destitute as this region is beginning to suffer

famine: thus we take him to replace the groom who

rebelled. As he has a small, lively face and is

endowed with great energy, I let him take care of my

horse.

Soon we are

crossing vast expanses of sandy soil that sometimes

forms small hills, on which the rain has produced

heavy erosion. Here, as everywhere, thanks to clever

irrigation, it has been possible to make the once

sterile land productive and the people are growing soy

beans, string beans and other vegetables, all kinds of

fruit, especially khaki, precious kinds of wood, and

finally the mulberry, which has everywhere led to the

breeding of silkworms.

After crossing

the Tcha-kine-oune-san by a high pass, we arrive at

nightfall before the town of Tchangto with its

crenellated walls. The double-walled gate is wide

open, but to my great surprise, we do not see any

guardians, or bystanders, or merchants, the people

generally seen in these kinds of places. We enter the

city: here we find the same solitude, the same

silence, grass is growing in the streets, and despite

the noise made by our horses, no one comes running as

we pass, no door opens for us, it is worse than the

castle of Sleeping Beauty, where at least the sleeping

figures were visible. Here, nothing, not even a human

shadow, and I would have thought the city uninhabited

if we had not met one or two stray dogs and seen in

the midst of the evening mist, vague lights shining

through the opaque paper frames of a few windows. We

go through the gate opposite the one we came in by and

remain silent for a long time, as if the silence of

the city had been contagious. I turn to take a last

look at this strange city, and see the heavy gates

close quietly all alone, as if they had been pushed

shut by the spirits of the dead. I learn at the next

village, where we spend the night, that the city was

almost completely abandoned as a result of a terrible

cholera epidemic. This terrible scourge frequently

decimate villages throughout the country.

We have seen how

Koreans seek to disarm the spirit of smallpox, they

use a system similar for almost all diseases: for this

purpose, a small rectangular table is garnished with

food, two vases of flowers are placed at each end, and

a drum is suspended above, then the husband and wife

who have someone in their house who is sick sit on the

ground beside the table and call the spirit of the

disease, striking the drum and ringing a bell to

invite him to the dinner thusoffered and thereby

hoping to divert his anger; but to keep away the

spirit of cholera, there is a special preventive

method: it is simply to fix the door a painting

representing a cat. Here is why, it is ultra-logical:

The bite of the rat gives cramps, as too does cholera.

What is it that the rat fears? The cat. So it will be

the same for cholera. QED, if I remember my math.

The next day,

for the first time, the weather is really cloudy and I

have to insist to get the caravan moving, but the sky

soon clears, my men sheer up, and one of them soon

brings me my morning bouquet. Here is how this

practice was begun. My principle when explorating, as

I have already said, is to show myself initially very

demanding for all that concerns the discipline of the

convoy, sure that everyone will submit easily, feeling

close to authority; then, as good habits are soon

taken, after that we only have to show ourselves kind

to all. So my men, delighted with me, every day

endeavor to respond to the care I take of them and

their horses. Thus one afternoon, I made a sign to me

grooms to pick an unknown flower; after having admired

it and not wishing to despise the poor thing, I put it

in my buttonhole, and from that moment on, every

morning I am offered a small bouquet, which I fix in

the same way to my clothes.

So, reader, if

you ever undertake an exploration and want to be loved

by your companions, do like me and you will be offered

flowers every day by a trousered Isabelle.

Next comes a new

ascension of Tcha-kine-oune-san, which, after making a

half-circle, now presents itself under the form of a

mere hill.

The rain that

has been threatening us from morning finally falls, I

immediately put on my rubber sheet, and all my men

wrap themselves in huge coats of oiled paper that

cover the entire body, while the head disappears

beneath a large triangular cap of the same material.

These sheets of paper, before becoming coats, poor

devils, have played a much more glorious role; because

of the Chinese characters with which they are covered,

my interpreter recognizes them as the exam papers of

aspiring scholars. Nothing more curious than to see

these venerable theses walking through the

countryside. If there is one thing in the world that

Koreans hate it is the rain. When a drop surprises us,

all my people ask to stop at the next village, and

though I jokingly call them sissies, they, who are

usually so merry, remain downcast. This is not only on

account of the miserable straw shoes that protect

their feet very imperfectly, but is mostly based on a

religious custom of public prayer to obtain water from

the sky. The Mandarin responsible for making the

request on behalf of the people, must, if the prayer

is granted, stay out in the rain until nightfall, and

my men fear that if they receive a drop of rain

stoically then the powers above will believe that they

desire to be wet in perpetuity.

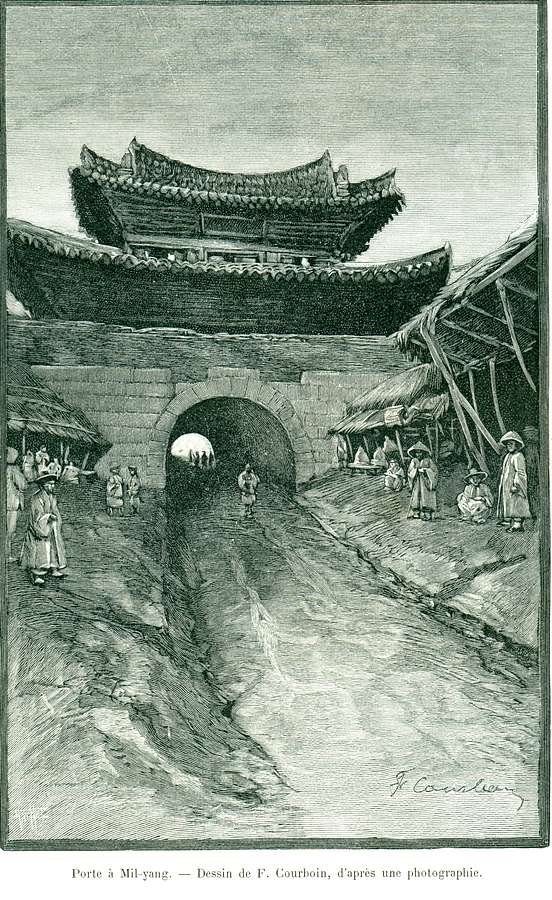

So that day,

after walking for more than two hours in the pouring

rain, I finally yield to the repeated requests of all

and stop at Mil-yang, which we suddenly see, together

with the great river. The city rises in an

amphitheater on a hill, something exceptional in

Korea, because we have seen that people generally live

at the foot of hills, probably a survival of some

ancient custom, of which it would be good to seek the

origin. This ancient city presented itself to us in a

most picturesque manner. Atop the hill is the yamen in

ruins, of which remains only the elegant, magnificent

roof supported by huge columns between which you can

see the sky. Two or three temples and a few public

buildings covered with multicolored tiles stand among

many thatched roofs, beneath which lie the

half-destroyed walls covered with moss. They dominate

a magnificent plain, where here and there grow

picturesque groves of trees of all kinds, around

which, thanks to a resurgence of greenery, thousands

of wild flowers grow; the river crosses the plain

lazily, its sleeping waters shining with a white

metallic glint. The interior of the old city is of the

greatest archaeological interest: its streets,

monuments and even houses, especially those of the

nobles, mostly in ruins, have a personal nature in

their outlines; their delicate and whimsical

sculptures prove that here a truly native

architectural art is seeking to liberate itself from

Chinese influences.

Several artistic eras are represented

here in such a happy way that Mil-yang for me is like

the Nuremberg of Korea.