Voyage en Corée

2. (Voyage in Corea Section 2)

by

Charles

Varat

Explorer

charged with an ethnographic mission by the

minister of Public Instruction

1888-1889

— previously unpublished text and pictures

Le Tour du Monde, LXIII, 1892

Premier Semestre. Paris : Librairie Hachette et

Cie.

Pages 289-368

Section Two [Click here for the

other sections in English: Section One,

Section Three,

Section Four,

Section V.]

Gravures (all)

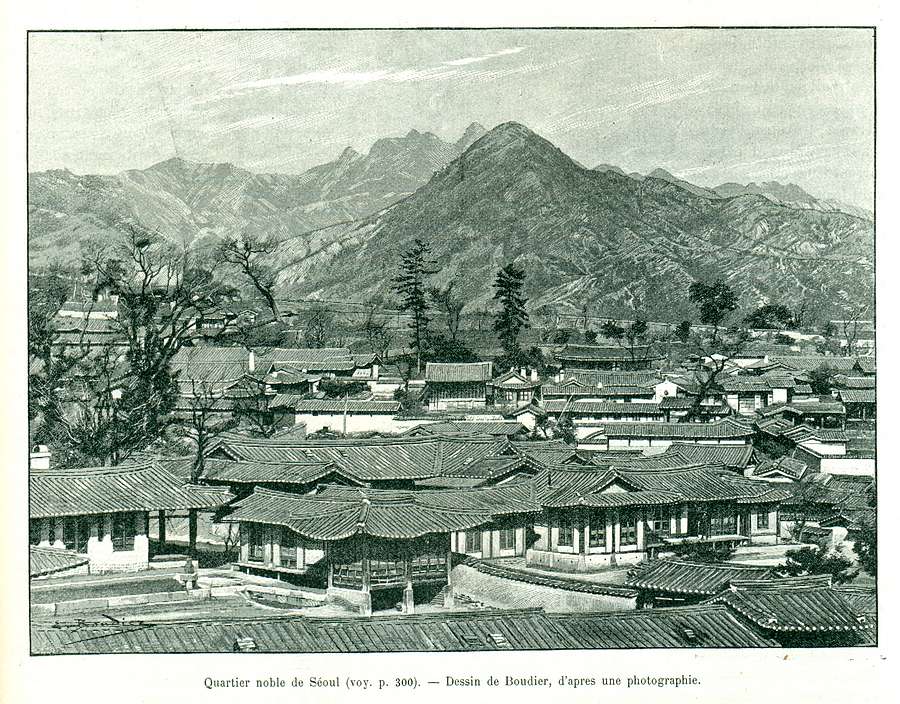

Ethnographic overview. - The Seoulites. -

Their costumes. - At the market. - The furniture and

utensils. - Human Portage. - Seoul at night. - Which

way forward? - Preparations for departure. - The

caravan. - Farewell. - On the road. - Fall of Ni. -

Passage of the Han-Kiang. - A Buddhist monk. - Bulls.

- A lisic post. - Prisons and torture. - First act of

authority. - An inn. - Horses. - Bread.

I heard repeated everywhere in Europe,

America, Japan and even China, that Korea is a poor

country from an ethnographic point of view. Indeed,

there is, at first glance, nothing sadder, poorer,

more miserable than a Korean city, even the capital.

After long wars and successive invasions of their

country, the kings of Korea, to avoid in future the

greed of their powerful neighbors, not only forbade

entry into their kingdom to all foreigners and exit

from it to their own subjects, but even forbade mining

and promulgated sumptuary laws which unfortunately

stopped domestic production, hitherto so brilliant,

and forcing individuals to hide their wealth. This

gave rise to an obvious disrepair which has misled

many people. But if one takes the trouble to lift the

veils, some curious observations are available

immediately to you! and what a great ethnographic

harvest awaits you outside the magnificent monuments

that still bear witness to past splendors! We will try

to show readers this by taking them on walks with us

through the noisy population of Seoul, whose customs

we will study, then taking them to visit merchants and

craftsmen to examine the domestic products. The

streets are usually crowded; all classes of society

mingle there, with their various costumes, dominated

by white cotton clothes, whose use is most prevalent.

Nothing is more curious than seeing

confused in one crowd mandarins on horseback, noble

ladies carried in their palanquins, scholars,

merchants and farmers, all busy, female slaves with

their breasts exposed, monks, soldiers, sorcerers,

blind beggars, children of every sex, every age,

swarming in the most commercial districts of the city,

particularly around the main streets, beside the

cisterns. These are circular, built using blocks of

stone, the water is two feet below the ground, and it

is drawn at every hour, the women are especially busy

at it. It is in the center of Seoul that the

agglomeration is densest, especially in the vicinity

of the building occupied by the huge bell that tells

people the different times at the same time as it

recalls their municipal obligations. Not far off is

the bazaar of the Court, the wood and livestock

market, where foodstuffs and fruits, etc. are also

sold. And amidst the noisy crowd men, women, children

move freely. However, high class ladies are allowed to

go out only if they are in a hermetically sealed

palanquin, or if on foot, wrapped in a coat of green

silk that covers them from the top of the head to the

lower body and crosses over the face, allowing only

enough light in for them to see their way. The wide

sleeves, raised to the level of the ears, droop

ungracefully along the body.

The women of the people, rarely

beautiful, walk about not only with faces bared, but

often their bare breasts appear between their little

camisole and the wide belt of their high petticoat.

They go, in this state, to visit the merchants, making

purchases of all kinds: rice, fish, chicken, cakes,

etc. while their children play noisily in the streets

or stop in awe before acrobats or some Korean clowns.

In summer, these poor little kids are

barely dressed, I often met some whose only clothing

was a small cotton vest that stopped short at the

level of the breasts. As for men, the greatest variety

prevails in their clothes, different for each of the

eight classes in society. I have already described the

dress of a prince and of the common people. The middle

class is distinguished from the latter in that over

the jacket and trousers, men usually wear a kind of

coat that crosses the chest, falls very low, and is

slit on each side, from the belt down. It is closed by

ribbons, that each one ties with the greatest elegant

possible, the Korean knowing neither buttons nor

hooks: this garment is usually white or very light in

color, almost always of cotton, sometimes of silk,

never wool. It is padded in winter with cotton. The

bourgeois, instead of having bare ankles and straw

shoes, have a free-floating tape of cotton, binding

the bottom of the trousers to socks stuffed with

cotton, which enlarge the feet considerably, the feet

being shod in topless shoes of wood, leather, felt,

paper, etc.. Finally the band of cloth around the head

of the wretched is replaced for the wealthy by a thin

tissue that is covered by a horsehair hat with a wide

brim, flat and round, topped with a small truncated

cone intended only to house the topknot that married

Koreans have on the top of their heads. The hat, thus

placed on top of the head, is held in place by two

long ribbons that are tied under the chin. This kind

of head-covering is made of felt, paper, straw,

horsehair, palm, etc.., and in the latter case, it is

woven in openwork, so as to allow the air, the sun or

the rain to enter freely through the open mesh. It

sells at very high prices and is of a rare perfection

of execution and form. I know many Parisian ladies who

will not hesitate to order some once they come to know

of them. Korea seems to be the land of hats: they are

made in all kinds of shapes, and I have nowhere seen a

greater variety, from the crown of gilded cardboard

for the provincial governor to modest headband of the

peasant. In order to learn more about the production

and the main styles, I visit Korean hat-makers, and

learn all the processes of their industry. I continue

my researches in the same way, visiting successively

the maker of fake hair for ladies, the cloth merchant,

the dyer, the makers of ribbons, pipes, arrows, shoes,

in short, all craftsmen of the city.

Here we are in a street where they sell

furniture; I find objects from different eras. The

oldest are lacquered or painted in contrasting colors

of the most brilliant effect, and some are enriched

with thin bands of ivory or bone which form a square

cloisonné, into which has been poured a thin layer of

melted horn, whose golden transparency bestows a

special glow to the vivid paints it covers and

protects. Others, less ancient, are painted black and

beautifully inlaid with mother of pearl, a natural

product of the country, giving to such furniture an

incomparable richness by the beauty of the designs and

the brightness of the light they store up. Finally,

today others are made today of polished wood decorated

with copper, the forms which are strangely reminiscent

of our furniture of the Middle Ages. I brought several

samples of the different types just described: they

are true specimens of Korean craftsmanship.

Unfortunately we only found them in the homes of

mandarins and nobles, or very rich people, because in

Korea as in Japan the common people have no furniture.

Seats are unknown in these two countries: people just

sit on the floor, and sleep there, too: the poor on

the floor, and those who are more fortunate on mats or

between two small thin mattresses.

The pillow of the poor is a small

elongated cube of wood, about 30 cm long and 15 high;

the rich have a pillow of cloth stuffed with feathers

and finished with two discs, about twenty centimeters

across, inlaid, painted, sculpted or painted and

generally embedded in a copper ring. As for beds, they

are almost unknown, and is only sometimes used among

the governing classes. But everybody eats from a small

hexagonal table 60 cm in diameter by 20 high, and

regardless of the number of people dining together,

everyone has at least one. Large chests, 60

centimeters high and about one meter wide, serveas

storerooms; generally they are manufactured in pairs,

placed one on top of the other, so that they appear to

form a single cabinet. Finally, each person hangs his

clothes on long sticks over a meter in length, often

decorated with paintings, silk, copper, etc. To

complete our information on Korean home furnishings,

we must add all the utensils necessary to household

use, either in stone or wood, pottery or metal.

In this regard I would point out to the

reader that copper vases are only used in winter

because of the smell they emit in the summer, where

they are replaced by porcelain, stoneware, earthenware

etc.. Ancient ceramics of these kinds enjoy a high

reputation among the Chinese and Japanese in

particular, who claim to be indebted to the Koreans

for this industry, which they have taken to a high

degree of art. The oldest pieces I brought back in

these various types of production are distinguished by

the simplicity of their slightly heavy shape, the

unity of their color, often greenish, gray, red and

sometimes white, and finally their beautiful glazes.

The designs that sometimes decorate them are purely

geometric - we will return to them later. As for our

samples of modern pottery, they recall in form and

decoration our European products. One of our drawings

shows how Korean potters work nowadays.

The floors of the houses here are mostly

covered with oiled paper to prevent the smoke from the

chimneys below from entering the rooms through cracks.

Paper is, however, used for all purposes of life, to make clothes, hats, shoes, quivers,

fans, parasols and screens, as well as lanterns,

vases, boxes, wallets and children's toys of an

exquisite taste. The writer, drawer and painter use it

directly, or attached to an extremely fine silk

fabric. Finally it is used for printing, and the

characters and drawings are of outstanding

typographical quality. Korean paper far exceeds the

best that China and Japan have produced. It is

manufactured, for the superior qualities, using

mulberry bark, and it emerges, according to the

processes that it has been subjected to, under the

most diverse aspects regarding color, granulation and

delicacy. Its strength is matched by its flexibility:

it is the finest paper in the world.

Next we are shown some samples of objects

related to lighting: candle-holders in wood, marble,

bronze, inlaid, with the most varied forms. As for the

lanterns, they are even more bizarre; I brought some

interesting specimens. We finally acquired some very

curious old weapons and modern musical instruments,

embroidered cloths, wood carvings, bronzes and jewelry

of high quality, proving that the Korean knows all

there is to know about the most delicate arts and

knows how to put a personal touch on things.

Now, to end our day, all that remains is

to show our readers some new drawings allowing them to

be present at the creation of some of these objects,

drawings where our Korean artist shows us the weaver,

the founder, the turner of copper, etc. in the midst

of their work, and complete the series with a few

sketches taken from nature, where we will see the

different ways of carrying things adopted by his

countrymen.

In China, human porterage is almost

always on the shoulder, at the ends of a pole where

burdens are balanced; this method is not used in

Korea, but all the other methods are employed. Witness

this old beggar, who is holding out her

begging-basket, and this charming girl with a broken

cup for the china mender. A little further, this poor

devil is carrying his pack over the left shoulder by a

strap and begs by tapping on a hollow wooden bell. A

shopkeeper and his son also use a pack, but passing

the strap diagonally across the chest, and it is the

same with children who present their wares in the same

way. Here are some carriers with differently charged

frames on their backs; others carry their burden on

the back by two straps passing over the shoulders.

Women often put their loads on top of the head; as for

their children, they carry them on their backs as in

Japan, and, after long walks they sometimes let

themselves be carried on the back of a parent, a

servant or a lover. The saddest form of porterage is

certainly that of the cangue, but the absolute limit

comes when someone gets his jailer to wear it for a

fee, while he himself quietly smokes his pipe.

If I have written at some length on human

porterage, it is because there are few countries where

it is as important as in Korea. The fact is that the

almost complete absence of roads in this country,

which is absolutely bristling with mountains, means

that there are, so to speak, no carts, and as the

horses are almost exclusively in the service of the

government’s posts, all merchandise is carried on

men's backs. As if they wanted to show us that day all

the means of transport employed here, now we suddenly

have to clear the middle of the street to let pass a

group of Korean soldiers, half dressed in European

style and with their guns slung over their shoulders.

They are escorting the minister of war, who is carried

on a beautiful palanquin of the kind that bring

important people to the Legation. These open chairs

are sometimes mounted on one wheel, which bears the

weight and so requires less carriers. Closed

palanquins are also employed, but these, far from

resembling the chairs

of China, whose shape recalls those formerly in

use among us, are instead simple cubes one meter high.

The traveler, who sits with his legs crossed under

him, is unable to move; a time in one is therefore

especially tiring for Europeans. These palanquins are

used not only to carry men and especially women, but

also to carry gods in processions. There exist even

smaller forms, employed in funeral ceremonies to bring

home the mortuary tablets, that is to say, the good

spirit of the deceased.

We continue our walk and come across a

strange procession, consisting of a number of

musicians accompanying a young man whose two

attendants are holding his horse. It is a graduate who

has just successfully passed the exams. His hat

indicates his rank; it is decorated with two curved

antennae up to 40 long, all covered with flowers. Our

hero makes his official visits in this pompous attire,

which he must unfortunately pay for with his own

money. A little later, we are joined by a stylish

rider that we recognize as a courtier in his suit and

hat of hair from which two small wings project

horizontally. He is followed by a servant on foot

carrying on his shoulder, in a net bag, a round box of

copper, 25 cm diameter 12, which sparkles in the rays

of the sun with golden reflections. Struck by the

ceremonial aspect of this new form of porterage, I ask

my companion if this vase is not a tin of provisions.

He laughs.

"Ah! I have it, I said: It’s a great box

of sweets.

- You're nowhere near, he says, this

vase, always made of metal, with a lid and no handle,

plays a much more important role in Korean life. It is

mandatory for all, as each has his own and never

leaves it behind, even during visits and especially

when traveling. The poor carry it themselves; the rich

have a special servant attached thereto who has to

keep it at all times in the most sparkling

cleanliness, available for the master. Even the

Mandarin himself, in all the pomp of his official

visits, treating it as almost equal to his own sealsm

employs it as a counterweight on the horse carrying

them.

- But what is its use?

- It is used day and night, in solitude,

and in meetings, whenever the need arises. Here's how:

on a sign, the clerk hands it to you and it is gently

slipped under the long coat. Its function once

performed, carefully putting the lid on, removing it

from the asylum where it was briefly hidden, it is

returned to the attentive servant: he knows what he

has to do, while we continue peacefully the

conversation as if nothing had happened. In addition,

this object serves as a spittoon and replaces if

necessary a candle-stick once its owner has disposed

the cover to this end: finally, precious container! it

is often used as a pillow by the poor of this world.

Therefore, given its quintuple use in Korea, added my

companion, I advise you, when you speak, to call it

the "National vase."

- No, I said, all civilized peoples use

it, but I find that here it is no longer "chamber",

since moves freely everywhere, or "night" because we

meet it in sunlight, so it should be called, given its

multiple functions, the "indispensable."

While we were conversing, gradually the

fog comes on, and everyone hurries back to his home,

because it is forbidden to men, for fear of being

arrested, to circulate in the streets of the capital

from a certain hour of the evening. Only important

people and foreigners are allowed out, and they do not

abuse the permission, given the absolute lack of

lighting in the city, which is so poorly maintained

that even with lanterns we risk breaking our bones a

hundred times. This leaves only the police outside,

the blind or some servants of Mandarins, charged by

these with urgent commissions justified by a wooden

disc called "for circulation", on which are burned the

name of the master and his position. These precautions

are taken only against thieves. However, should one

meet a lady, one must avoid looking at her, turning

one’s face towards a wall. Only women are free to move

about the capital after nine o'clock in the evening,

and they take the opportunity to walk about and

breathe with face uncovered, which is forbidden during

the day. We leave them to their happy freedom, and

return to the Legation, where we find the night

watchman already at his psot. It is a special custom

in Seoul that all the important houses have a servant,

who walks through the courtyards and gardens as long

as darkness. He is armed with a sword and a square

iron bar about 2 meters long, to the tip of which are

attached sound-producing rings that he must constantly

shake to warn thieves that he is on guard.

I learn all these details from my

gracious hosts who every day, not only help me with

their advice, but take from people on all sides the

information necessary to facilitate my journey through

Korea. Oh! the good, the great friends! they do

everything for me and do not even allow me to thank

them!

The first cold weather is starting to be

felt, but I am assured that it will stop soon and then

I'll have almost two months of good weather, which is

just enough. I must hasten my departure, although I am

delighted that my stay in Seoul, where I was able to

study so agreeably the topography, architecture,

customs and various productions, while putting

together a large ethnographic collection. From all

this it appears to us that the Korean by his physical

appearance, manners, habits, characteristic products

of all kinds, etc.., is absolutely different from his

neighbors, to the point that if one of them is placed

in a crowd of Chinese or Japanese, he will be

immediately recognized. Similarly, a Chinese or

Japanese in Seoul is immediately recognizable by his

costume, his facial expression, language, etc.. This

very clear difference, together with the diversity of

types that we encounter here, increases the difficulty

of determining to which branch of the human family we

should attach the Korean. But we will try to do so by

crossing the country and collecting all the documents

related to this topic. But which road to take to try

to achieve this? In reality nothing is more simple:

first we should study the main routes that have been

covered so far.

The oldest known route is that which goes

by land from Beijing to Seoul: a Chinese ambassador

once made a very interesting description of it,

recently translated by Mr. M-F. Scherzer, the late

diplomat to whom the future seemed to promise a

brilliant career.

Here is the route they followed: they

went to Beijing to Yong-Ping-fu, Ning-yan-cheng,

Cheng-king or Mukden and Feung-Hwang-tchang, from

there, passing the palisade marking the frontier of

the Empire, they reached Itcheo and there entered

Korea over the Ya-lou-kiang (in Korean Ap-Nok-kiang)

and from there passed through Ngancho, Hoangtcheo and

arrived in Seoul.

The road that Hendrik Hamel from Gorcum

followed comes next. He was shipwrecked on Quelpaërt

in 1653. He is transported by sea with his companions

to Hai Nam and from there over land to near Seoul,

through Riong-Om-Na-jiu, Tain-Chon-jiu, and finally

Kai-seng. After long years of slavery, the survivors

are forced to take an almost parallel route, also

touching Kai-seng, Kongjiu, Chon-ju, and then on to

Nam-on, where they reach the sea. One night they

manage to escape by boat to the island of Goto, and

from there reach Nagasaki.

This is a summary of the interesting

story, published by Hamel after thirteen years and

twenty-eight days of captivity.

Two centuries later, M. Oppert visit the

main cities of the Gulf of Prince Jerome and reaches

Seoul. Carles then appears, who follows the route

followed by the ambassadors from Seoul to Wigu, from

where he begins a new journey passing through Wi-Won,

Chang-jiu, Hamheung and Won-san, and from there takes

the direct route Seoul, used by the Japanese and the

Russians and recently traveled by Colonel

Chaillé-Long, who also visited Quelpaërt, like Hamel.

Three expeditions have been directed at the White Head

mountain. In 1886, Messrs. James, Younghusband and

Fulford leave Beijing and reach the Paik-tu-san

through Manchuria.

In 1890 and 1891, two expeditions to the

famous mountain are undertaken by Sir Elliot and Major

J. R. Hobday makes known the results in a very

interesting topographic map. Finally, Sir Ch.-W. H.

Campbell of the Consular Service, China, has recently

told of his curious expedition to the far north of

Korea. Here is a summary: taking the direct route from

Seoul to Keum-seng, he reaches the coast near Koseng

and follows it up to Won-san, where he takes the road

followed by Carles to Ham-heung, then reaches

Pulh-cheng and continues along the coast directly to

Kapsan, Un-chong and Po-chon to Peik-tu-san; on his

return from this magnificent journey he makes a double

detour at the last cities just mentioned to visit

Hyei-san and Sam-su, then returns by the road he

followed up to Koum, where he takes the road of the

ambassadors as far as Pyengyang, then via Hoang-chu

finally returns to Seoul.

These travelers having had great success

with their journeys, all that remains for me to

accomplish as a journey of exploration in Korea is to

travel from Seoul to Fousan.

Mr. Collin de Plancy approves this

project absolutely, but he advises me to go through

Taikou, the capital of Kyengsang-to. This almost

doubles the length of the journey, because of the

difficulties of the road, but offers a much larger

ethnographic interest than the direct route. There is

no hesitation. I hasten the packing of all that I have

bought in Seoul to ship it directly from Tchemoulpo to

France, and acquire all that is necessary for my

exploration: stove, cooking-ware, wine, preserves of

all kinds, flour for my bread, and finally an old oil

can, 60 × 30 centimeters, which, surrounded by coal,

will serve as an oven. I also order some large cards

in red paper, 15 centimeters by 8, with my name in

Chinese characters; if I was in mourning, I should,

according to the rites in Korea, have used white

paper. These cards, contained in a huge portfolio of

oiled paper with ornaments and a brass padlock, will

be borne ceremoniously by the servant responsible for

depositing them with the mandarins of the districts

that I have to cross. Finally, respectful of the

customs of the country, I offer myself the necessary

vase-brass candlestick of which the reader already

knows what to expect. That is, with my scientific

instruments and my personal belongings, all of my

luggage, contained in four wooden boxes that must be

joined in pairs on the Korean ponies. Meanwhile, Mr.

Collin de Plancy takes care of my internal passport.

It is sent to me in a huge envelope of 25 cm × 10,

edged with blue, covered with Chinese characters

printed in the same color, and bears, in addition to

various characters drawn with a brush, three huge

seals of mandarins. The passport, double in size, is

decorated with identical burdenss.

It remains for us to resolve the

important question of money. The only form of money

known in Korea is what are called “coppers,” small

copper coins pierced at the center by a square hole

which serves to string them together; every hundred

coins are separated from the next by a straw knot for

easier counting. At present 1350 coins are worth one

Mexican piastre, about 4 francs. The quantity of cash

to be carried therefore increases the number of horses

of the caravan and the danger of being stopped by the

brigands. I do not know how to calculate exactly the

amount needed for my journey, no European having made

it before, and besides, along the way I want to buy

anything that seems interesting from the point of view

of my collection. Mr. Collin de Plancy, with his usual

tact, overcomes the difficulty by obtaining a letter

of credit on the Treasury. This missive, a magnificent

specimen of Korean paper, is written entirely in ink

and with two red seals, here is the translation:

"Order of the Minister of Foreign Affairs

to the mandarins of each locality.

"We have received from Mr. Collin de

Plancy, Commissioner of the French government with us,

a letter in which he says that his compatriot, Mr.

Varat, on the orders of the King of France (!) has

come to study our habits, our customs, our manners,

and to make at his own expense a collection of all our

products, artistic, industrial and agricultural, that

he will offer to his country.

"For this purpose he wishes to cross

Korea and reach Fousan via Taikou,

"That is why we are sending this letter,

to assure him of a good room (?), to provide

everything he needs, and to open a credit on our

Treasury. Provide him with the sums he may request,

against his receipt, which we will then refund here.

Bow down and obey.

"Signed: Minister of Foreign Affairs."

Armed with this precious document, all

that remains is for me to organize my caravan. Mr.

Collin de Plancy is so kind as to give me one

interpreter from among the scholars of the Legation,

called Ni, who has learned our language in part

through the Fathers and then through our eminent

representative. To increase my standing as a French

Mandarin, he also offers two Korean soldiers

responsible for guarding the Legation as an escort.

Finally in his goodness, not overlooking any detail,

he finds a Chinese cook skilled in our style of

cooking, and orders people to find the eight horses

and grooms that are necessary. The ponies are brought

on the eve of my departure, I at once inspect them.

The biggest is destined for me; despite its

exceptional size for Korea I can mount it without

setting foot in the stirrup. I must, however, avoid

showing myself to it because at the sight of my

European clothes, it immediately rears up on its hind

legs. This is a habit it religiously preserves during

the whole trip. Five of the other horses, though very

small, seem to have all the necessary qualities to

make the trip. But the last two seem unacceptable: one

has a sly look presaging unpleasant adventures, and

the other seems to me absolutely incapable of doing

even two days of walking, holding its poor head sadly

between skeleton legs, I gently lift its head to see

the eyes and realize that it is blind in one. The

first, I am assured, seems to have faults it has not,

and the second is hiding all its qualities: in

addition, if I do not like them, they can be changed

along the way. I agree therefore to keep them in order

to avoid delays. As for the men, I worry little: it is

up to me to train them. Besides, I could only obtain

their support and that of their horses until Taikou,

where I will have to reorganize my caravan to go to

Fousan. Finally, as nobody has made the trip before,

we will have to ask information about directions as we

go. My horse is chosen, my interpreter chooses for

himself, despite my advice, the little horse that

looks unreliable, then it is the turn of the two

soldiers, and finally of the cook. Three horses are

intended to bear the cash, my scientific, culinary,

personal luggage, etc.., I decide the load for each,

and in order not to tire my memory with the composite

names of my companions, I decide to call each by the

position he will occupy in the caravan, which, given

the complete absence of roads, will have to walk in

single file. Contrary to the demands of ritual, I

place at the forefront the fiercest of my two

soldiers, to whom I leave their weapons to spare their

military pride: this warrior will be named One, and

the groom who accompanies him Two, then come the

grooms Three, Four, and Five, responsible for guarding

the baggage. Six is my cook and Seven a groom. My

interpreter and another groom are called Eight and

Nine, another groom and my second soldier, responsible

for carrying my orders along the small column are Ten

and Eleven, Twelve is the owner of my horse and I am

the last, tragic Thirteen, a number that is as good as

any other.

I had decided, against all Korean

customs, to travel last, in order to be able to keep

an eye on all my little troop, to prevent gaps

occuring, take care of every need, and avoid any

discussion about the place, it being most exposed to

attacks by tigers, and I never took the head of the

column except during night marches, to hasten the

pace, being certain, given the dangers of bandits and

others, that I would be followed closely by my people.

When everything is thus settled, I give

my men rendezvous for the next day and spend my

afternoon paying my last visits to all the people I

had the honor of being presented to in Seoul. I meet

tem all again in the evening at the Legation, for the

farewell dinner that Mr. Collin de Plancy kindly

offers in my honor. What terms can I find to express

here how grateful I am to our esteemed representative

and his amiable Chancellor, Mr. Guerin, for their

cordial welcome, for all the services they have

rendered me in organizing my trip across Korea, for

the care they took after my departure to complete my

collection by purchasing many documents that all kinds

of impossibilities had prevented me from obtaining? It

is a debt that all my friendship and dedication will

never allow me to fully repay, no more, alas! than all

those others I acquired during my trip around the

world, for I found everywhere in the diplomatic

agents, sea captains, customs employees, missionaries

and all Europeans the most charming welcome. So I am

happy to finally be able to thank them all publicly

and I hope that the echo of my gratitude will bring

back to them over there, the loving memories that I

keep of them all.

The hour of our departure has come: it is

with a truly heavy heart and moist eyes that I embrace

our excellent consul general and his amiable

chancellor, who have become my best friends. They

accompany me to the door of the Legation, follow me

with their eyes. Alas! the caravan soon turns right, I

wave my handkerchief one last time and sadly we move

on through the city to reach the South Gate. Here we

wait for my interpreter, whose home is nearby.

Impatient at not seeing him arrive, I am about to go

in search of him when he finally appears. He tells me

he has escaped with the greatest difficulty the

heartbreaking farewell of his mother, his wife and two

small children, as these good people are struck by the

terrible dangers that we will inevitably encounter on

our journey. Finally we are in the saddle, and we

enter a little ravine og red earth covered with tall

Japanese cedars, whose bushy, dark green branches,

stand out against the blue sky. This place is a

favorite hiking destination for the inhabitants of the

capital; all the suburban countryside with its rice

fields, conical rocks, distant mountains dazzles and

delights us. The weather is beautiful and relatively

warm.

Suddenly I hear a cry; I look and see my

unfortunate interpreter has been thrown from his

ridiculous mandarin-style saddle, perched so high that

his feet touched the head of his horse, which, as I

had foreseen, is already beginning to shy wildly. I

jump down from my small European saddle and help

master Ni up. He looks upset because it is not only

his first attempt at riding, but also his first

voyage, and this unfortunate beginning leaves a very

strong impression, although he admits to having been

more afraid than hurt. This time, I want to have the

vicious pony carrying luggage, but one of my soldiers

ask me to give it to him in exchange for his own,

which is very sweet. I reluctantly agree; the saddles

are changed, and master Ni climbs back onto his

pompous seat, where he looks, half buried in the

cushions, like a walking Buddha, blessing the Korean

countryside.

We soon reach Narou Kay, where we cross

the Yang-kiang; the landscape is beautiful: far off. a

range of blue hills blends gently with the horizon,

while in the middle of the valley flows the river, a

huge body of sleeping water, which reflects the blue

of the sky and the green of the hills, with an

intensity of luminous transparency which has an

inexpressible charm. We cross the river on two small

boats which, fortunately, make several trips.

Distracted for a moment, I hear loud cries, I turn

around and see the last horse still in the sampan jump

into the water with all my scientific equipment. The

current bears it away, but luckily we are able to

catch it and bring it back, but unfortunately some of

my instruments are lost due to moisture. I grumble at

myself and my people, because I am convinced that if I

had followed this last voyage as the other seven, I

would not have had to regret the irreparable loss of

my barometer, my photographic plates, etc.. To prevent

such a disaster recurring, I now require, at river

crossings, that each horse be held by two grooms, one

in front and one behind, something which was not done

on this last crossing. We continue our journey past

Sovindo, Na-Ouen, then we cross the first hill, the

Sa-pian. We meet a mendicant monk dressed in his

yellow robes and armed with a stick, with which he

strikes a small wooden instrument in the shape of a

large European padlock. He is appealing to public

charity, and his purse seems empty, just as most

Buddhist temples are deserted in Korea. Buddhism was

introduced to China by the fourth century, it soon has

so great an influence that Korean monks start to

spread the new faith in Japan, where they are so

successful that 624 Saganomago, regent after the death

of M'mayadono-oci, organizes Buddhism as the official

religion and appoints to the dignified rank of So-zio

(Supreme Pontiff) and So-dy (Vicar General), Kam-ro

and Taku-Seki, Korean monks from Kou-doura (Hiak-sai);

they and their successors make the greatest

concessions to the Shintoist priests, sacrificing

purity of doctrine to personal interests. Later

Buddhist monks in Korea as in Japan, took part as

armed soldiers in the internal political divisions

which agitated the two countries.

But at the end of the fourteenth century,

the new dynasty installed in Korea, after some

persecutions, gradually leaves Buddhism completely

aside. With that, its influence diminishes rapidly.

Now most of the pagodas are almost abandoned and

monasteries are often used for joyous gatherings of

galants, whose activities there are far from religious

matters. Finally, the alms that a few monks still

collect are given less from devotion than from human

kindness. Such is, while Confucianism grows, the

unfortunate state to which Buddhism, once so

prosperous, has been reduced in almost all the

provinces, with the exception of Kyeng-yang, where its

has retained some influence, contrasting with the

poverty that monks are reduced to almost everywhere

else. Everyone here, even the buddhists themselves,

admit that in a few generations there will be nothing

left but a memory of this cult.

We continue our journey through a

beautiful valley, full of rich harvests, scattered

trees, with rice fields beautifully arranged.

Harvesting is in progress, and as there are no carts

or wagons, given the state of the roads, the transport

of fodder is done on the back of magnificent bulls.

They carry a strange arrangement, consisting of four

poles two meters high, connected together by four

cross sticks that are placed on the animal’s back, to

keep them in balance together with all the rice straw

they enclose. The animal thus charged seems to be

carrying on its back a whole cartload of straw. These

ruminants, despite their powerful stature, are

extraordinary gentle, so they are never castrated.

They obey the slightest sign, thanks to a very simple

device which consists of a wooden ring passed through

the nose and attached to the top of the head by a rope

whose action is so violent that in all circumstances

it prefers to do immediately what it is told. Could we

not apply this system in France and so avoid the many

accidents, often fatal, suffered by our hardworking

farmers? If the experiences made at home are

successful, which I am convinced they will be, I shall

be amply rewarded for my expedition to Korea. Only

bulls perform farming work here; horses cannot,

because of their small size, be used for this purpose.

We cross the Kum-Koutan, behind which we

find in the plain the same crops of millet, beans and

peppers, etc.. Where the paths serving as roads cross,

we often encounter a huge square post more than 2

meters high. Roughly carved, it represents a Korean

general, rolling fierce eyes and gnashing his teeth;

his chest is decorated with various inscriptions

indicating the names of roads, distances, etc.. It

might be called a ‘lisic’ post (from li, the distance

of measurement used here). At some junctions four or

five of these poles can be seen together, that from

far off have the appearance of mandarins standing

chatting together. A strange legend is told about

them, and I entrusted it to the professional secrecy

of a journalist who has somewhat abused it; however,

as it seems curious in form and idea, I cannot resist

telling it again.

In very ancient times, the Minister of

State Tsang led his daughter, who was young, very

beautiful and not yet married, to a secluded room and

said: "My child, if someone has a good harvest must he

keep it for himself, or give it to one of his

neighbors and friends? – How can my august father ask

me such a question? Of course he must keep his harvest

for himself and his family. – Very well, you have

yourself pronounced your sentence: you are my flower,

my fruit, and you shall be mine alone." And he made

her his wife. In desperation, she committed suicide.

Soon came a great drought in Korea, and despite all

the sacrifices offered to the gods by the king and all

the mandarins, the skies remained tightly shut, and a

host of people died of starvation. The king then

invited all the officials to join him to consider the

matter, and great was the astonishment when Minister

Tsang presented himself at the meeting with his hat

covered in dew, although the sun was shining most

ardently. The king immediately had the general

arrested and he confessed his crime in the midst of

tortures. He was accordingly condemned to be cut into

pieces, and therefore his effigy was placed on the

posts along the roads to remind everyone that the

punishment of the offense of one often affects the

whole country.

Suddenly, by a strange coincidence, just

in front of us we see an unfortunate prisoner, his

head held in a cangue, walking along painfully with a

guard on his way to prison. This corresponds in horror

to the interrogation with various tortures of which we

show two terrifying drawings. All these atrocities are

justified in Korea by the idea that any misconduct

undermines the family, the basis of humanity, and thus

deserves the highest punishment.

A fourth ascent leads us up onto the

plain of Ma-chu-kori, which means "Food of the king's

horses." Here I finally notice that one of our steeds

is dragging its poor legs in the most pitiful way. I

approach the unfortunate beast, and observe that its

load of copper cash has been doubled and it is none

the better for that. At once I give the order to

unload the poor animal, which then, suddenly relieved

of the weight it had been supporting with great

difficulty, balanced on stiffened limbs, falls to the

ground, but then immediately rises courageously. I

caress it with my hand, and realizing that this, the

anemic pony I had at first refused, has been

absolutely sacrificed, I order an exchange of saddles

with the most outstanding of the horses, which is only

lightly loaded. A great clamor from the horse owners.

"I do not accept any comments, because it is just, I

say, that the strong bear the heaviest burden, and

whether you like it or not, it will be so throughout

our journey, because I want to arrive safe and sound

without losing either man or beast." We then resume

our march, the men very unhappy and I delighted by

this incident, which will earn me in the future,

thanks to the results that I expect, the absolute

confidence of my escort. Two hours later, we are at

Ta-ri-net, where a bloody battle took place between

Koreans and Chinese, then we gain Han-ko-oune. Since

night is falling, we stop at the inn. My horse steps

over the cross-bar at the bottom of the outer gate,

while I bend in half to avoid hitting my forehead on

the beam above. We enter a large courtyard, in the

center of which stands a huge tree trunk, one meter

high, topped by a stone on which scraps of pine wood

are burning whose brilliant light illuminates the

entire inn. To the right of the gate lies the kitchen,

to the left the commons where bulls, cows, calves,

pigs, roosters and chickens are lodged. Along the far

side are the rooms for travelers, built up on small

masonry vaults for heating by the Korean method.

Finally, on the left, is the open hangar where our

horses that are now being unloaded will find shelter.

They are installed one by one, the rump toward the

wall and the head turned towards the courtyard, facing

the fire. Before them, a beam placed transversely and

supported on poles 60 centimeters high prevents them

from escaping; at the same time it serves as their

manger, small square troughs having been carved into

it. While the ponies are eating a first course of rice

straw, in the kitchen a great soup of various kinds of

beans is cooked which is served piping hot, then the

meal ends with a third course identical to the first.

While I am inspecting my horses, I notice that they

all have a large incision in the nostrils so that,

during hot weather, they can breathe more easily and

avoid heat-stroke. While the animals are eating, the

grooms weave huge straw covers for them, doubling the

thickness of the part designed to cover the necks and

chests of the ponies, so as to protect them completely

from the cold, to which they are very sensitive. One

starts to act as a bad neighbor to the rest with a few

kicks: at once a wide belt of plaited straw is passed

under its belly, the ends of which are attached to two

beams in the roof. When it tries to kick again, the

rope automatically tightens and the animal, suddenly

suspended in the air, calms down immediately. I should

also draw the reader's attention to their strange way

of shoeing horses, laying them on their back and tying

the four feet together with a rope. The Koreans,

having noticed that horse-shoes are frequently worn

down more on one side than the other in this country

of mountains, often cut the shoe in two, so that only

half has to be replaced.

While I am taking care of my caravan, my

dinner has been prepared; I find it served on a small

Korean table. I sit down on a suitcase which, with the

rest of my luggage, a mat to sleep on and a wooden

pillow make up all the furniture of my little room. It

is bare, with white walls, the ceiling beamed, and the

floor covered with oiled paper, to prevent smoke from

entering. This inspection done, I began to eat. My

soup once eaten, I ask my Chinese cook for bread. He

looks at me bewildered. He does not know French, but

he must know English, from what I'm told, so I try:

"Give me some bread", he remains stunned, " Geben Sie

mir Brod," his dismay increases, "Datemi pane", he

flees in panic. Has he finally understood? He soon

returns, not with bread but with my interpreter. "Ah,

I say to Ni, this fellow, who claims to know all the

European languages, knows decidedly none. I just asked

him for bread in French, English, German, Italian, and

he did not understand, tell him in Korean. – But he

does not know our language. – Say it in Chinese then.

– Sir, I pronounce it too badly. – I am starting to be

angry. – I'll give you some bread, replies Ni, and

gives me a piece, saying: “This is all that is left.

"Heavens, I thought, how am I going to teach my cook

to make bread and cook it in the oil can?” I was quite

puzzled, then suddenly an idea came to me: Since you

are a scholar, I say to Ni, if you do not speak

Chinese you should at least be able to write the

characters? – Yes, he replies. – So call Six (the

number of my cook), and ask him in writing if he knows

how to read and write. The latter, having read,

replies that he understands perfectly. This then is

how I communicate with him. I tell my interpreter, he

writes, the cook reads, and I am served. My dinner

finished, I close my window of wood and paper, fasten

my door with a rope wrapped around a nail prepared for

this purpose, and spend a good night in my camp-bed,

which is prepared by the two soldiers, now become my

orderlies.