Voyage en Corée

1. (Voyage in Corea Section1)

by

Charles

Varat

Explorer

charged with an ethnographic mission by the

minister of Public Instruction

1888-1889

— previously unpublished text and pictures

Le Tour du Monde, LXIII, 1892

Premier Semestre. Paris : Librairie Hachette et

Cie.

Pages 289-368

Section One. [Click here for

the other sections in English: Section Two,

Section Three,

Section Four,

Section V.]

Enravings (all)

Korea

opened. - Chefoo. - Visit to the consul. -

The departure. - How I met a Korean prince

and what happened.-Tchemoulpo. - On the

road. - Arrival in Seoul. - A Japanese

hotel. - At the legation of France. - My

life in Seoul. - Administrative and social

organization of Korea. - Topography of the

capital and its surroundings. - Its

monuments. – Telegraphy, posts. etc.. - Our

representatives

This travelogue is

only a fragment of the volume that Mr.

Charles Varat is to publish soon on Korea.

This volume will be divided into three

parts: the first will summarize the studies

that have so far been consecrated to this

country, so little known; the second will

contain the story of the journey, that we

give here today; in the third, finally, the

author will attempt to determine, from his

personal observations and from the work of

his predecessors, the ethnic character of

the Korean people. It is, therefore, only

the anecdotal part that we have detached in

advance of the work of Mr. Varat; it will

certainly allow our readers to anticipate

the interest of the rest.

Korea was once so

absolutely closed to the world, that apart

for the annual Chinese embassies tightly

controlled at the border of the

Green-Duck, nobody could enter under pain

of death. The missionary Fathers were the

first to brave the barbaric ban and

managed to cross during the night the

river that forms the border, although many

customs officers kept fierce watch. Soon

this route had to be given up, for the

Korean Government, informed of the

violation of its territory, had trained

dogs to pursue foreigners. It was

therefore on junks, manned by Chinese

Christians, that the Fathers, sheltered by

the islands of the coast, could transfer

to the boats of their future flock, who

risked their lives to introduce

missionaries into the country. They hid

from sight by the Korean orphan’s costume,

whose immense hat fully hides the face,

and prevents, given the rites of mourning,

any indiscreet questions. Today, thanks to

treaties, a simple passport is enough to

enter Korea either by land, crossing on

the Chinese border the Ya-lou-kiang, in

Korean the Apnok-hang, or on the Russian

border, the Mi-kiang, in Korean the

Touman-hang: or by sea by going from

Nagasaki to Fousan, Gensan and

Vladivostok, or vice versa, or finally

across the Gulf of Pe-chi-li embarking at

Chefoo for Tchemoulpo. I chose the latter

route: it leads more directly to the

capital, the starting point, and above all

the center for the ethnographic research

that I wanted to undertake.

So I left the

main line of the Messageries maritimes

from Marseilles to Yokohama at Shanghai

to take one of the steamers that go to

Beijing by way of Tientsin, with a

halfway stop in the charming Chinese

town of Chefoo. If I were to add a

qualifier to its name, I would call it

Chefoo-les-Bains. This is indeed the

Chinese Dieppe, where every year during

the summer, all the Europeans who have

grown anemic by a long stay in China, go

in crowds from all the open ports. They

find, thanks to the salt air they

breathe, not only health, but new forces

to resist the debilitating climate of

the Far East. Also near the Chinese town

rises a true sanatorium where you can

enjoy the kind of life found on our most

elegant beaches, thanks to the numerous

hotels that have been established, that

take turns in offering balls, dances,

concerts, etc.., and delightful

excursions at sea, or in the surrounding

mountains and valleys.

Hardly arrived at

Chefoo I go to find Mr. Fergusson, the

Belgian consul and vice-consul of France

and Russia, to ask him for some

practical information on my trip. He

tells me that the moment is badly

chosen, because recently marines from

the European fleets have had to land to

protect the consulates during the latest

riots that have troubled Seoul. "But

that is fortunately over. Could I

reasonably have come more than halfway

around the world and now be expected go

back the other way without having

entered Korea, the main purpose of my

journey?

--On reflection,

you can go to Seoul; but as for crossing

Korea to reach Fousan, a journey no

European has ever made, you must

give up the idea.

--Someone must

start, though, and I want it to be me,

having come absolutely for that

purpose.

--It is

impossible in the present state of

things, my interlocutor replies: famine

is beginning to be felt on the east

coast; you will inevitably fall into the

hands of bandits. They have begun to

organize themselves into bands,

attacking villages, looting houses,

raping women and massacring everything

that is offered to them ... even

travelers, he added with a smile.

-Your information

is not very welcome, but it cannot

change my resolution.

-You will change

your mind in Seoul. "

I remind the consul

of the fable of floating sticks, thank him

for his kind hospitality, and get ready to

leave by the first boat going to Korea.

I wait several

days, having missed the bi-monthly

correspondence, but am welcomed most

gracefully by the amiable British colony,

the time passes quickly and it is with a

real sense of sadness that on an evening

with a ball-concert I have suddenly to

board the boat for Tchemoulpo. The steamer

only stops briefly at Chefoo, and my

sampan has barely reached it offshore

before we set off into the dark, damp,

cold night. There is nobody on deck; I

enter the saloon, but it is deserted;

finding myself alone, I return to my cabin

and regret more keenly than ever the

pleasant gathering of elegantly dressed

women that I have just left. I summon them

into my thoughts and soon the glide

smiling around me, so that I dare not open

my eyes, fearing to see their charming but

fleeting images vanish. So I fall asleep,

gently rocked by the sea

After a night of

happy sailing, in the morning I go up onto

the deck. The ship is following the

Chinese coast that is unfolding before our

eyes with its many undulating, treeless

peaks blending with a melancholy sky full

of gray clouds. The captain of the Suruga

Maru and his mate show me rare

kindness, as too an Englishman traveling

by sea to Fousan. Other travelers are

Japanese or Chinese, one of them speaks

French admirably and I use him as an

interpreter with his countrymen. During

lunch, the captain asks me if I have met

Koreans. I said that in Japan, aboard the

steamer that was to take me from Kobe to

Nagasaki, a few moments before departure I

saw coming towards us two large boats

filled with Japanese officials and a group

of strangely dressed men. I was told that

it was a Korean prince with his retinue. A

quick inspection of the features of their

faces and their clothes, that were

completely new to me, made me feel sure

that a rich ethnographic field was open to

me in Korea, I could not take my eyes off

them.

The Japanese

officials, after having ceremoniously

installed aboard the Korean Prince, wish

him a good trip and withdraw, and we weigh

anchor. As soon as we under way, the

prince, a young man of about twenty-five

years with a rare native distinction,

struck by the curiosity with which I am

considering from afar himself and his

companions comes towards me smiling. I

quickly stand up, and advance toward him:

we meet, and for lack of a common language

allowing us to understand one another, we

express our feelings for each other by a

friendly pantomime as lively as it is

vivid. I offer him a cigar, he proffers

cigarettes, takes in a friendly manner my

watch from my pocket and makes me inspect

the one that he has just bought. Then it

is the turn of our eye-glasses, our

clothes, everything that can be the

subject of a mutual curiosity. All this is

accompanied by laughter, handshakes, words

in English,

Japanese, Korean and French, that we

certainly do not both understand. The

prince's three old advisers and many

servants gathered around us rise,

following

our example, when our curiosity is

satisfied, and we retire to our cabins,

with a thousand polite expressions, to the

astonishment of a group of English men and

women who look on smiling and cannot

explain this unexpected sympathy.

The next morning, I

am sitting on the deck, not far from the

lovely ladies I have mentioned, when the

prince suddenly appears, not in his

costume of pink silk covered with gauze,

but wearing only wide baggy trousers of

white silk and a short blue jacket.

The prince rushes

toward me, his face expressing great

anxiety, mixed with a strong sense of

trust. He proceeds to express his trust at

once, by raising his broad sleeve to the

shoulder, to show me with concern the

thousand bites speckling his skin, that is

exceptionally white. I make him understand

by signs that he was probably a victim of

mosquitoes. He tells me that the matter is

much more serious, and suddenly, turning

his back, he lifts his jacket, lowers his

pants and shows me the first quarters of a

star that I hasten to eclipse by covering

it, to the sound of the laughter and cries

of indignation of the young misses

attending this unconventional

consultation. To end it, I take the prince

by the hand, lead him gravely to the

bathroom and invite him to take his place

there. He understood, thanked me, and that

was how, before arriving in Korea, I saw

every side of a prince of Korea. This

story greatly amused the indulgent captain

of the Suruga

Maru, and my very amiable

companions: that is why I decided to tell

it here.

The next morning,

awakened by the sudden stop of the noise

of the boat’s engine, I go up on deck and

am delighted by the wonderful situation of

Tchemoulpo Bay. It is one of the most

beautiful I have seen in my life.

Picturesquely jagged mountains rise along

the coast and on the islands that form the

harbor, sheltering it in a most complete

and charming manner in an absolute nest of

greenery that is now lit up by the first

rays of sunrise.

Without losing a

moment, and leaving my luggage on board,

since I do not know where I could store

it on shore, I jump into a sampan. A

quarter of an hour later, I am standing

at last on Korean soil, enjoying once

again the strange feeling of suddenly

finding myself alone in the midst of a

population of which I know neither the

language nor the customs or costumes.

Hundreds of Korean laborers, legs

half-naked, are transporting soil

destined to form a wharf. Many porters,

their trousers and jacket of white

cotton, are carrying materials on a

wooden hook roughly squared, similar to

ours, that is kept in balance on their

backs by a rope passed round the

forehead. Their hair is tied in a knot

that rises like a horn from the top of

their heads. All are barefoot or wear

shoes of straw, where the big toe is not

separated from the other toes as in

Japan; Koreans, moreover, far exceed the

Japanese in size, and their faces have a

very different character.

Here and there,

women are bringing food to their husbands.

They are very ugly and unsightly, shave

their eyebrows into a thin line that

describes a perfect curve. Their oiled

hair, which is thick and black with red

lights, is formed by I know not what

artifice into a huge tress of hair that

loads down their heads. They all seem

packaged, rather than dressed, and I am

especially surprised to see that most of

them allow their breasts to hang

completely outside of their clothes, which

are open horizontally on the chest.

Further away several youths are playing,

shouting loudly, and if I had not seen

their mothers, I would have taken them for

women, as my eyes are deceived by the

grace of their features, their long

floating tresses and singular trousers

that looks like a puffed-out skirt. I

leave the port and enter the Korean town,

if you can give this name to a huddle of

hundreds of thatched roofs, which rise

three to four feet above the ground,

forming veritable dens one can only enter

half bent.

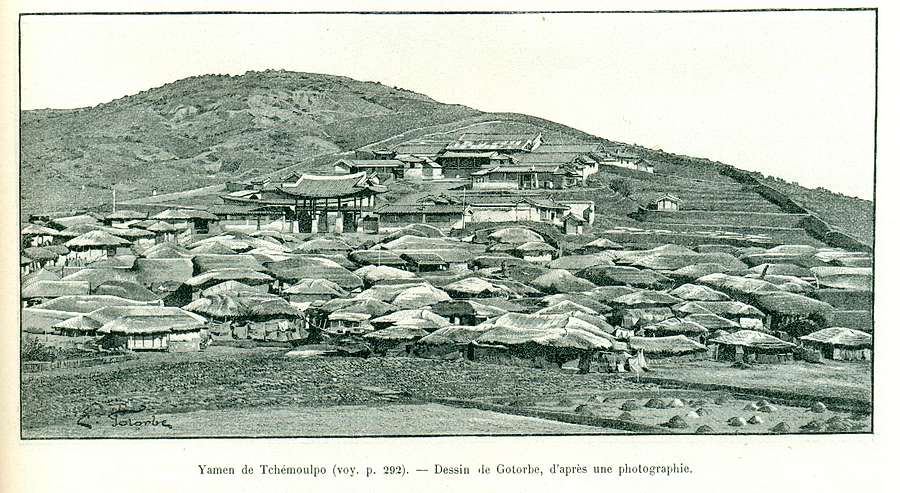

One street and a

few narrow lanes make up this large Korean

village, that was only born yesterday as a

result of the opening of the port of

Tchemoulpo to Europeans. It is dominated

by the vast yamen of the governor, the

enormous roof of which, slightly curving,

recalls similar constructions in China,

but with notable differences. Indeed, seen

from afar this huge building seems to have

only windows; that is because the

building, raised a few feet above the

ground, extends over a vast wooden

platform so that each window is in fact a

doorway allowing people to circulate on

the kind of veranda formed around the

building by the overhang of the roof. It

offers a magnificent view of the bay. It

seems absolutely closed in by the islands,

which form a vast maritime amphitheater of

the most imposing effect. In the center

stands a small island covered with

greenery, and on the right, the Seoul

river, flowing in capricious meanders,

sparkles in the sunlight. I head in that

direction, and pass through the Japanese

concession. I believe myself transported

back to Nippon again.

What

a contrast between the misery of that

Korean hamlet and this clean, cheerful,

busy town, where the Japanese have

brought with them their manners, their

customs, their uses! They have therefore

absorbed the greater part of the trade,

and their establishments grow daily in

importance, a few Chinese firms

providing the only competition. I walk

up the wide street lined with charming

houses that passes through the middle of

the neighborhood, and arrive at the

European concession, occupied only by

two or three traders. I make the

acquaintance of kind Mr. Schœnike, the

Commissioner of Customs, and his second,

a merry Frenchman, Mr. Laporte, who

together take me to meet the young and

charming British Consul, where we are

received most graciously. These visits

made, I moved into a small European

hotel run by a man from Trieste. He

urges me to fetch my luggage as soon as

possible from the boat if I do not want

to have it carried up on bearers’ backs,

because the tides here range from 26 to

30 feet, and the sea will soon withdraw

several kilometers. Indeed a small ship

anchored in front of our steamer is

already high and dry and being kept

upright by enormous beams: it looks from

afar like a huge spider. I therefore

make haste and am back with my boat

before the vast bay is transformed into

a huge plain of sand that allows you to

walk dryshod to the verdant island of

which I have spoken. This abrupt change

occurs twice a day and changes beyond

recognition the general appearance and

tone of the landscape, passing

successively from green sea to yellow

sand.

During the rest of

the day the small European colony throws a

party in my honor and urges me strongly to

go to Seoul by a small daily steamer

service that has recently been organized.

But since the boat does not arrive the

next day, I take leave of my new friends

without further ado, thank them warmly and

set off. My little caravan is composed of

two horses for my luggage and instruments,

a third for me, finally three grooms, the

owners of the horses. These men dressed

like laborers have a pipe about 1m. 20

long which, when they are not smoking it

they place between their backs and their

jacket. The end of the tube that is sucked

emerges behind the neck, while the metal

bowl can be glimpsed much lower down,

which offers a most bizarre appearance

when they walk along, arms dangling. We

stride across plains, valleys, hills,

sometimes in the middle of cultivated

fields, sometimes through tall grass.

Everywhere horses, or ponies rather, or

superb bulls, sometimes yoked to a

rudimentary cart. I will not see these

carts again in my journey, because they

only travel between Tchemoulpo and Seoul,

one of the few places in Korea where there

is a certain length of what might be

termed a true road.

We arrive at the foot

of a steep hill, the Pel-ko-kai, which is so

steep that I cross it on foot to spare my

horse, then I continue to follow the valley,

intrigued by the repeated halts my men make

at small Korean huts, above the roof of

which is a long pole carries a little oblong

wicker basket suspended in the air. I

continue my way alone through the

countryside, caught up from time to time by

my grooms. Soon, I soon come to know the

cause of their frequent disappearances by

their staggering walk; it is absolutely

confirmed, when one of them falls on his

back so awkwardly that he breaks his long

pipe.

I would have had

rather grim traveling companions if the

drink had turned them nasty, but they remain

at the stage of great tenderness, offering

me fruit they have bought somewhere, and

vehemently insisting that I smoke their

great pipes. I manage to keep them in this

good disposition and prevent them abandoning

the horses again, by making them understand

by signs that if I am pleased with them,

they will have a good tip on reaching Seoul.

Thus, after passing Sadari-chou-mak, we

arrive at the small village of

Ori-kol-mak-chou, where we have to stop to

rest and feed the horses. I refuse to enter

the so-called inn after a single glance has

shown me its perfect lack of cleanliness,

and stay outside, sitting on my trunks. My

presence arouses great curiosity among the

people who surround me respectfully. They

are highly intrigued by my dress, especially

my gloves, my leather gaiters, and politely

ask to touch them. After a break of about

two hours we finally leave, following a

Chinaman with a beautiful mount. He now

takes the head of the caravan, to my great

satisfaction, as we are walking much faster

now because I encouraged my increasingly

excited grooms to follow him. We are now

crossing a much flatter region and soon

reach a branch of the Hang-kang, which we

ford; now we find ourselves in a vast plain

of sand, probably covered by water in the

rainy season. Here and there the stones have

accumulated in this little Sahara, where

horses and men, who are barefoot, advance

with difficulty, their feet half sinking in

the sandy soil. Finally, we see in the

distance the river, which we cross by boat,

and thus arrive at Mapou, the real port of

the capital, although it is ten miles away

from it. The town is built on a plateau

somewhat elevated above the river. The

houses, consisting of a raised ground floor,

are nothing like the dens of Tchemoulpo.

They are full of goods, indicating the

commercial importance of the city, which we

cross in order to take the road to Seoul.

We are now in the

midst of beautiful market gardens, where a

variety of vegetables are grown, especially

a gigantic kind of cabbage; here and then

are fruit trees and finally around us wooded

hills rise in tiers. This magnificent

vegetation contrasts with the small desert

we have just crossed. Later, we encounter a

beautiful alley of gigantic willows that I

long to follow. But I have to give up, it is

not on our way, and night is coming,

bringing with it the closing of the gates of

Seoul.

After climbing

Mountoro-tsintari, we therefore urge on our

horses that were unable to keep up with our

Chinaman, and I begin to despair of arriving

on time, when we suddenly see in the mist a

monumental gate surmounted by a

Chinese-style pavilion, long walls with

their battlements outlined in the red glow

of sunset. Soon we pass under a huge porch,

the gates close behind us: we are in the

city.

A street as wide as

the Champs-Élysées opens before us: it is

lined with thatched huts, and behind them

stretches a plain of tiled roofs: I have the

impression of entering a huge village. I

walk in the midst of a bustling crowd,

half-blinded by smoke, and yet I see no

chimney. The reason is that Korean homes are

built on small stone arches rising about

three feet above the ground, the

fire burns at one end and the smoke escaping

from the other asphyxiates the passers-by,

but warms in passing everything inside the

house. The houses are built of rough stones,

always of a single floor and with the

particularity that on the outside walls,

each stone is set in a rope that goes round

it. Now the lanterns are being lit in the

shops. These, as in Japan, have no

storefronts, no seats or tables. Everyone

sits on the ground, unless, given the small

size of the cluttered room, purchases are

made from outside. I should add that all

these stores are very poorly maintained.

Soon we leave the

main road to follow narrow streets, where on

my little horse I dominate head and

shoulders above the edges of the roofs.

Everywhere are deep stinking streams we have

to avoid. They are often crossed by small

bridges, formed by a narrow slab of stone

where my mount slides constantly. Night,

increasingly dark, half hides the sad

spectacle that surrounds me, when we finally

arrive at the Japanese hotel. Singing,

shouting, laughter emerging from inside

inform me that many travelers are already

installed. As soon as I enter, a charming mousme

crouches at my feet, touches the ground with

her forehead and gives me, graceful as can

be, a tiny cup of tea, I take it and tell

her to prepare my room. She replies that

there is no more room; I insist, she takes

me by the hand and makes me inspect all the

rooms, pulling open successively in their

grooves the wooden frames covered with paper

separating them, without their tenants

seeming to pay any attention to our

unexpected presence. Alas! the hotel is

full. What can I do but appeal to our

consul? But how to find his home in a city

of over 200,000 inhabitants? Fortunately the

little mousme

who welcomed me is as intelligent as she is

comely, and with an Anglo-Franco-Japanese

vocabulary, she understands and indicates

the desired address to the grooms.

I am so glad that I

could kiss the sweet mousme; to tell the

truth, I do, and she is so far from being

angry that she will not accept any

gratification for her kind hospitality, and

even helps me to mount, accompanying my

departure with a bright silvery laugh, it

all seeming such fun, for kissing is

absolutely unknown in Japan. We resume our

journey in the night, and for nearly three

quarters of an hour we once again cross this

huge city. Finally, after following the

course of a nearly dry stream, broad and

shallow, we cross it by a beautifully paved

bridge without parapets, and reach the

legation of France. Korean soldiers surround

me, I give in my card, and soon I am

received in the most delightful way by our

eminent representative, Mr. Collin de

Plancy.

I had the honor of

seeing him in Paris on the eve of his

departure, which preceded mine by two

months, and here he greets me like an old

friend, offering me the most complete

hospitality. Together with his amiable

Chancellor, Mr. Guerin, he proves that I

have long been impatiently awaited by

installing me in the room prepared for me. A

few moments later, we sit down at table. Oh!

the charming, exquisite, good evening! and

how sweet it is in the antipodes of Paris to

talk about France and mutual friends left

behind! We are so happy to be together and

evoke thoughts of all that we love, that the

night is far advanced, when, by an energetic

effort of our will, we finally separate.

This is the beginning of my visit to Korea,

much simpler than I had expected and ending

under the hospitable roof of excellent

friends.

Here is how we

organized the daily use of my time in

Seoul. Mr. Collin Plancy has spread the

rumor that a French traveler is buying

samples of all the productions of the

country, and is at the legation every

morning to meet with merchants. They duly

arrive very early and in large numbers,

with their goods, which I examine with the

greatest care in terms of my Korean

ethnographic collection, ruthlessly

rejecting everything that comes from

abroad. Mr. Collin Plancy is kind enough

to put at my disposal some native

scholars, his secretaries, to whom he

teaches French every day. They give me

many explanations on all the objects of

which I do not know the use. They rectify

the prices, sometimes ultra-fancy, then

the sellers accept or refuse our offers,

so that I lose no time haggling and thus

miss some purchase, while the merchants

bring back to me the next day objects they

refused to surrender the day before.

Our lunch is often

complemented by the presence of dignitaries,

Korean ministers and mandarins, whom I

hasten to photograph, to their great

satisfaction, on their departure. It takes

place very ceremoniously, because according

to the rites, we accompany them to their

palanquins, consisting of a kind of chair on

which is thrown a leopard skin, it is placed

on two long poles that are lifted with

cross-bars; just as the Mandarin sits down,

the many carriers emit a lengthy guttural

cry. They repeat this at the exit and all

along the way, to remove passers-by from the

route of the procession and again on

arriving at the yamen, to make the gates

open, as happened at the legation, thus duly

warned in advance of the arrival of Korean

dignitaries.

In the afternoon we

visit Seoul with my gracious hosts and some

scholarly secretaries, entering shops with

them to buy everything that seems to offer

some ethnographic interest. We also visit

major official figures, European or native.

They welcome us in a charming manner in

pretty little houses, single-storied,

miniature versions of the yamen I described

in Tchemoulpo. In front are the rooms for

receiving visitors, behind are the women's

rooms, where no one enters except the

husband; finally the commons are scattered

throughout a fairly well maintained garden.

One enters after passing a small entrance

courtyard where servants stand about, who

charge a good price for admitting

favor-seekers and merchants having some

business to propose.

In ordinary houses,

the reception rooms open directly onto the

street, from where you can see all that

happens in the interior since the doors are

usually open during the summer.

We were also received

open-heartedly by Bishop Blanc, the Bishop

of Korea, Father Cotte and their colleagues.

They even give me various objects found

during the excavations being performed at

this time for the construction of the

Catholic church. The ground has already been

leveled on top of a small hill, from where

the cathedral will soon proudly dominate the

capital. I also visit the nuns who arrived

on the boat which preceded ours. They have

already opened a school and collected

hundreds of small children of both sexes,

whom they instruct in a maternal way and who

seem very fond of them. How could it be

otherwise with these holy women? One has

dedicated over twenty-five years of her life

to missions in Senegal, and the other, a

charming young woman of a rare beauty, has

just abandoned all the joys of the world to

embrace her heroic career. They are assisted

by a young Chinese sister, who rivals them

in sacrifices and tenderness. We often

complete our day by visiting some monuments,

then we go in for dinner, where, thanks to

my kind hosts and some attachés from

European legations who are invited, we spend

evenings that I count among the most

beautiful of my life.

I hardly need to say

that we often spoke of the organization of

the life and manners of the capital. Seoul

is to Korea what Paris is to France, because

the centralization is identical and

dominates here as at home, across the

country. It was only in the early days of

the Ming Dynasty in China that the king of

Kaoli, Litan, left Khai-Tcheu and settled in

Seoul, attracted by its magnificent

location. Indeed, in the north, the mountain

of Hoa-chan circles around the city like

great armor; to the east lies a chain in

which each pass was formerly guarded, while

far to the west lies the sinuous coastline

bathed by the sea, and to the south the

Han-kang forms a kind of belt. Seoul since

then has remained the capital of the

kingdom. This is where the king rules with

absolute power his 16-18 million subjects,

because he wears the triple crown: as high

priest, he officiates for his people; as

father of the nation, he administers it as

his own family, and finally as guardian of

the safety of all, he decides on peace or

war, and no one can touch, even

involuntarily, his thrice holy person

without deserving death. Such veneration

mingled with such authority soon meant that

the rulers remained completely shut up in

their palaces amidst women, concubines and

eunuchs; this seraglio often abused the

royal isolation to squeeze the people, who

nonetheless loved their king, knowing him

completely innocent of their misfortunes.

This situation was maintained until and

throughout the minority of the present king.

The Regent, a man of ancient prejudices,

hating everything coming from abroad,

ordered at bloody persecutions against the

Christians in the kingdom. This provoked, in

retaliation, various military expeditions by

Russia, France and the United States. The

external situation was darkening every day

for Korea came when the present king reached

his majority. He, his mind very open to the

ideas of modern progress, understood the

dangers to which his country was exposed and

finally allowed access to Korea by

foreigners, contracting with them many

treaties of friendship, peace and trade.

If the foreign policy

of Korea was changed beyond recognition, the

general organization of the country remained

exactly the same, only the king abolished

his harem and began reorganizing his army in

the European way. But the wonderful

counselor, the counselors of left and right,

who monitor and report to the king

everything about the administration, were

retained. Likewise with the public

organization, thus subdivided: the

department or court rituals, established to

maintain the habits and customs of the

kingdom; the ministry of offices and

employment, which appoints for all positions

men who have passed the necessary

examinations; the tribunal of finance, in

charge of counting the people and taxes; the

ministry of war in charge of the army; the

tribunal of crimes, which supervises the

courtrooms and ensures compliance with the

criminal laws; and finally the ministry of

public works, which is responsible, in

addition to its special area, for everything

regarding trade and the organization of

official ceremonies. Now comes the practical

operation of this administration: the head

of each province is the governor; after him

come the heads of districts, the number of

which amounts to three hundred and

thirty-two, the number of days in the Korean

year; then come the mandarins at the head of

the major cities, and after them, the mayors

of small cities, villages or towns. Around

each of these dignitaries are grouped a

number of employees—nobles, veterans,

satellites, guardians of palaces, temples

and public buildings, spies, etc.., who to

varying degrees are part of what we call the

administrative class. Parallel to this

class, the nobility is divided as follows:

first the noble allied to the royal family,

and the children of those who helped to

found the dynasty or who have distinguished

themselves in public office. They occupy

varying degrees, depending on their family’s

closeness to the king, or the services they

have rendered to the State. A thousand

privileges were assured them, while the

ordinary people, oppressed, formed guilds in

order to fight against them and even against

the mandarins, as we shall see later. The

elected leaders of these corporations soon

enjoyed a real influence, so that this

system was adopted by all social classes, of

which the following is the order of

precedence: scholars, bonzes, monks,

farmers, artisans, merchants, porters,

sorcerers, musicians, dancers, actors,

beggars, slaves, then the class, considered

abject by Koreans, of killers of cattle and

tanners.

All men, except those

of the lowest classes, may in Korea

participate in the exams which alone open

the way to public office. The higher

examinations are based on knowledge of the

Chinese language and characters, philosophy,

poetry, history. In short they are the same

subjects as in the exams taken in China, but

have a lower real value. They are divided

into three levels, giving literary titles

corresponding with our bachelor, master,

doctor. Unfortunately, unlike the Celestial

Empire, one obtains public office in

accordance with one’s social position,

without being able, so to speak, to rise

above it; therefore, since the highest

functions are filled only by the nobility,

most middle class people prefer to take the

military exams, abandoned by the aristocracy

and which require knowledge of the army and

a single literary composition, or special

scientific exams, which give admittance to

the school of languages, where one graduates

as interpreter, dragoman, etc.., or schools

of law, charters, medicine, computing,

so-called the Clock, drawing and music,

which particularly open doors in the royal

household. So we can say that in Korea

education alone leads to honors, and it is

recognized as being so necessary by the

State, that a strict law states that any

gentleman who has not himself, and whose

grandfather and father have not held public

office because they could not pass the exams

is absolutely stripped of his nobility. That

is a happy corrective to the law forbidding

anyone from holding positions superior to

the class to which one belongs; such is the

social and administrative organization of

life in Korea.

Before talking about

monumental Seoul, a few words on its

surroundings. Near the South Gate is the

location of the place of execution.

Scattered bones of criminals are visible,

and sometimes their decapitated bodies, with

the head not far away. They are left here as

an example to the people for three days,

after which the family has the right to bury

them.

Farther off, lost in

the countryside and protected by the

Han-niang River, are some royal tombs

located in remarkable sites, finally here

and there are numerous granaries intended to

prevent famine in case of poor harvest or a

war of invasion. To the North, at the site

of the former capital, is a rare thing in

Korea, a stone bridge of twenty-one pillars,

covered with a marble deck. Nearby there a

stone pagoda recalling important historical

events, and a stele with Chinese characters

on its north face and Mantchoo characters on

its southern side, an inscription

immortalizing the establishment by the

Chinese emperor of the king who raised this

monument on a gigantic granite turtle 12

feet long, 7 wide and 3 high. Finally, four

forts located a few kilometers from Seoul,

Hang-hoa, Kais-yeng, Koang-Tiyou and

Syou-Ouen, defend the approaches to the

suburban countryside, which is admirably

cultivated despite the mountainous terrain.

Now let us take a

panoramic view of the Korean capital. If we

climb some central hill, we can enjoy a

magnificent view of the cone-shaped

mountains covered with greenery that

surround it; the highest are located in the

north and south. In many places we can see

the crenellated profile of the walls

surrounding Seoul in a vast circuit. They

follow, as in China, the curves of the hills

and are pierced here and there by a large

number of monumental gates. The two most

important have a double story in the Chinese

style and are of great architectural

character: one, that by which I entered, is

located to the west, the other to the east

and preceded by crenellated quadrilateral

enclosure, with a small entrance on the

north. On this side of the city extends

through the mountains a second walled

enclosure, which can serve as a retreat

camp.

Seoul is crossed from

west to east by a wide main canal carrying

water to the river from all the small rivers

that descend from the mountains and form a

multitude of little streams perpendicular to

the central canal. Alongside it runs a wide

road and three more narrow ones: all four

are intersected at right angles by a large

number of streets, the widest of which head

towards the old royal palace and the temple

of Confucius to the north of the city.

Finally, another very important road starts

from the South-east gate and joins the

central street in a regular arc. The rest of

the city is composed of a huge maze of

alleys and side-streets of every kind, which

communicate with each other, either directly

or by many arched bridges without any

parapet, crossing streams, rivers and canals

which may be torrential or dry depending on

the season.

The main streets, as

in Beijing, are blocked by a multitude of

shops, mostly made of wood and thatched,

where many merchants do business almost out

of doors. When the king comes out, all these

buildings are demolished, as in China for

the passage of the Emperor. Then the road,

once more over 60 meters wide and lined with

houses built of stone, then resumes its

character as a main artery.

The capital is

divided into several districts, including

the old and the new royal palaces,

completely surrounded by walls, together

with their monumental gates as cities within

the city. The noble district is

distinguished by its elegant houses roofed

with tiles and beautiful gardens with very

low walls so it is forbidden by law, under

the severest penalties, to look at one’s

neighbors; they must even be warmed about

repairs to roofs. This regulation applies to

the whole city. Manufacturers and traders

are generally grouped by profession: thus we

find the streets of fabrics, of furniture,

of pottery, the wharfs of iron, copper,

leatherware, the squares of fish, of

butchers, etc.. Finally, the Japanese have

their own center which they alone police;

the same is true for the Chinese, near whom

are grouped almost all the European

legations, residing mostly in elegant Korean

buildings adapted to our habits. As for the

suburban neighborhood, its buildings recall

the miserable hovels of Tchemoulpo.

Besides what we have

mentioned, the capital has special schools

for foreign languages, fine arts, astronomy,

medicine, and finally a hospital and many

other public institutions, all organized in

a very primitive way.

Some barracks are

built near the inner walls. In the center of

the city, in the garden of a private house,

stands a stone pagoda 25 feet in height,

formed of only two blocks of white granite

that time has robbed of its color. It is

divided into eight stages sculpturally,

which typify the Buddhist heaven by

representing the successive ages by which

the soul must pass to reach its complete

purification. Only the turning away from

Buddhism explains the burial of this

beautiful sample of Indochinese-Korean

architecture. Confucianism is truly the

dominant religious doctrine, and therefore a

magnificent temple to the great Chinese

philosopher has been raised in the north of

Seoul. It is sheltered on all sides by

mountains and protected by two rivers that

surround it before joining to the south.

This great religious institution has, in

addition to the Chinese-style shrine

dedicated to Confucius and his ancestors,

twenty buildings, some of which are very

spacious, to accommodate the many Korean

scholars who come to pursue advanced

philosophical courses. We feel that this is

the point where the country's real

intellectual power lies the and from where

it spreads to direct the administration, the

families, the morals of Korea. To complete

the list of religious buildings, it remains

for us to speak of the various temples in

high mountains near Seoul. Most of these, as

also the royal palaces, yamen, and other

places where a high authority resides, are

preceded by a wooden porch with a height of

30 to 40 feet and width of 20 at most. It

consists of two perpendicular beams joined

at the top by two parallel wooden rails on

which are nailed at right angles many red

arrows pointing towards the sky. The name of

Hong Sal Moun [Hongsalmun], that is to say,

“gate with red arrows,” is given to this

strange and slender building that I think is

of Tartar origin, not Japanese. After

crossing the elegant portico, we find in the

middle of a garden a Buddhist pagoda. It is

built in the Chinese taste. but a style

mellowed by a certain heaviness in the

general architectural lines and greater

simplicity in the details. We enter the

temple and we find Buddhas in stone, bronze,

wood, etc.. They differ from those of other

countries by a braid of hair at the top of

the head, where it stands up like a little

horn; we will explain later the origin of

this. I bought several of these Buddhas and

I found in the interior of each of them a

small copper box containing five more or

less precious stones, representing the

viscera of God. There were also perfumes,

various seeds, many Buddhist prayers in

Chinese, Korean, Tibetan, etc.., printed on

loose sheets, sometimes even entire books. I

would mention particularly a strip of black

paper 40 centimeters by 25 with gold

characters and drawings of rare workmanship.

Finally I could read, hand-written, the name

of the artist, donor, and the temple to

which it had been offered. The inscriptions

that decorate the Buddhist buildings are

almost always in Chinese characters painted

on wood panels or kakemonos of paper, silk,

etc.., always colored and sometimes gilded.

Sometimes it is possible to admire large

decorative panels, of several square meters,

covered with admirable paintings, depicting

Buddhist scenes of a strange and brilliant

execution, often very artistic as regarding

design and colors.

The finest

architectural specimens in Seoul are

certainly the royal palaces. I was unable to

see that which the king inhabits, because he

was in mourning during my stay, but I saw

two other much older and perhaps more

interesting palaces, although they were

partly destroyed during the recent riots and

bloodshed in the capital. It is accompanied

by Bishop Blanc, the fathers and Mr. Guérin,

who had not yet visited them, that we make

this interesting walk. Mr. Collin de Plancy,

who obtained permission for us, is,

unfortunately, retained that day by Legation

business. The palace entrance is preceded by

a monumental gate. Its architecture recalls

the huge triumphal arch in stone, with three

arched openings and surmounted by a double

roof, slightly curved, of the Ming Tombs,

near Beijing. On high pedestals two stone

lions stand guard outside.

We enter a large

courtyard, at the end of which stands the

great reception hall. It is a large building

made of wood, built on a double platform of

masonry that raises it aloft. A few steps of

white marble lead up to a peristyle

sheltered by a large double roof with glazed

tiles of different colors. They are

supported by projecting beams terminated by

colored dragon heads; the overall effect is

grandiose. The center of the monument is a

large hall supported by huge columns, tree

trunks several centuries old, on which the

whole structure rests. The back of this room

is decorated on the inside with mural

paintings in the Japanese taste, but with

much more violent colors and an interesting

naivety in the execution. They represent

mountainous landscapes lit by the sun,

represented by a white circle surrounded by

a double red circumference, and the moon,

represented in the same way by the same

contrasting colors. Amid this curious

decoration, which is not lacking in

grandeur, stands the dais of the king, that

is dominated by a huge gilt phoenix

suspended in the air, at whose feet stands a

superb fretted wood screen, wonderfully

carved. From this throne the king could see,

the entire facade of the building being open

for the purpose, the courtyard where stood

the crowd of mandarins, nobles, etc.., who

form the eight castes of Korean society.

Representatives of each, in special costume,

took their place, according to their rank,

in front of the throne, aligned with sixteen

marble markers separating the different

social classes. Such was the ceremonial of

the solemn audiences.

Going further, we

enter through a small door an elegant garden

where we admire a new palace in the same

style as the first, with the apartments

formerly occupied by the king. They are

spacious and present on a smaller scale

decorations similar to those described

above. The vast central hall is reserved for

funeral ceremonies, which take place at the

death of each king. The body of the

deceased, laid in a beautiful catafalque,

remains there under a wide canopy until

complete dissolution, and the products of

decomposition flow into the ground through

an opening below the body.

We then visit the palace

of the queen. It consists of a series of

kiosks in the most graceful Chinese taste.

Everywhere rise pretty pavilions with

upcurved roofs. All are united by small

passageways elegantly suspended. The whole

is of the most charming effect. From the

Queen’s sitting-room, decorated with

delicate paintings and beautifully lit, you

can enjoy a superb view over the

picturesque, mountainous area of Seoul,

while in the foreground lie gardens that

today are abandoned, but must have been

delightful, judging from the remains of

rustic swings, benches, vases and stone

planters, where we find all the marks of the

exquisite fantasy that presided over the

erection of the palace. The apartments for

the ladies of the court have been somewhat

sacrificed to the requirements of the

exterior architecture, for they consist of

small rooms, badly aired and even more

poorly lit. Finally a large building devoted

to the burial chamber of the Queen, is quite

similar to that of the king, but less

grandiose. We conclude this interesting walk

by passing through courtyards littered with

rubble of all kinds, with many bulbous

thistles and other flora, finally leading to

unfinished baths in white marble,

beautifully ordered, that the king was in

the process of having built, when a

revolution forced him to abandon this

splendid palace.

Then we visit various

outbuildings formerly inhabited by the

soldiers on duty in the palace and the homes

of officials. All of a single story and of

very little interest to visit, with the

exception of the small building which housed

the water clock in bronze which indicated

the time. The hours are designated in Korea

by the usual occupation they represent, for

example: lunch, dinner, etc. Beside the

water clock is the small room for the

astronomer who was responsible for

maintaining it and making daily observations

on a small square tower about 6 meters high.

It is now invaded by our Korean scholars,

and up there, in their white garments, they

evoke in my mind the memory of some ancient

mystery. As for our boys, they are scattered

across a vast field of turnips which they

are busily stealing. We remind them strongly

of the demands of decorum, which they

eventually meet while eating the fruit of

their thefts.

Finally we leave the

palace; night has come, and some of my very

amiable companions leave me to go home.

Meanwhile, all around us, on the mountains,

beacons are lit whose light, renewed from

peak to peak, tells the ends of Korea that

peace reigns in the capital, which is

informed by the return of same messages that

the kingdom is quiet.

We return to the

Legation, where during dinner the code of

light signals in Korea is explained. Four

beacons are lit in peacetime, that is to

say, one for every two provinces. In

wartime, the signal is more complicated. A

second fire, to the right or left of the

first indicates the province threatened. Two

beacons when the enemy is crossing or

landing; three fires when he has entered the

country, and four lights when fighting has

started. In addition to this light

telegraphy, the Korean government employs a

postal service whose relays are entirely

devoted to the service of the state. Shortly

after the signing of the treaties, the

government had beautiful paper made in Japan

for the manufacture of postage stamps,

unfortunately this material was destroyed

during the recent unrest in Seoul, and I had

the greatest difficulty in obtaining a few

specimens. In contrast, several telegraph

lines connect Korea to its neighbors, and

have even begun to expand across the

country. In Seoul there is a royal lottery.

The tickets, 20 centimeters square, are

printed in blue and covered with many

multicolored stamps; the administration

delivers only half to the buyer and keeps

the other for control. There is also a

national calendar, which had its fame in

ancient times. It was even preferred to the

Chinese calendar by the Japanese. Finally an

official journal appears each day in Seoul.

For a long time it was printed, but it is

now only published in manuscript. I give

here an extract of the numbers for October 5

and 6, 1888.

"The assistant

printer of the academy of high literature,

Ming-Chong-Sik, having refused office for

the first time, the king gave him leave.

- The Director of the

Office of historians Youn-Y-Sing, having

refused his appointment for the third time,

the king changed his appointment.

- The Ministry of

Rites made a report to the king where it

says:

When we congratulate

the Queen on the anniversary of her birth,

the 25th of the present moon, we wish to

offer congratulations as in the past. What

do you think? King's reply: It is better not

to do so.

- On the day

aforesaid should the Crown Prince

congratulate the queen?

- Decree: It is

better that he does not do so.

- The High Court

has made a report to the king where it

says We have arrested You-Chin-Pil and

Chong-Ym-Siang.

- Decree: Appoint the

undersecretary of the office responsible for

direct contact with the court of Peking,

Youn-Kiong-Tchou, secretary first class of

the office of censors. "

So every night I completed my

observations of the day with a wealth of

information given me by my very gracious

hosts.

Mr. Collin de Plancy is the kindest

man and most devoted friend I know, for his heart is

most delicate, and his mind is of the most

distinguished. He is certainly, among the many

diplomats I have had the honor of knowing in my

travels, one of our most outstanding officers. I had

the privilege, during my stay with him, to be present

at some of the political events that often arise in

these new countries, and I have always found in our

representative an accuracy of evaluation, a speediness

of execution, and a dexterity that do him the greatest

honor. No one knows better than he how to make the

adverse party sit down on a bundle of thorns with more

graceful correctness, and I must add that he is

admirably seconded by his chancellor, Mr. Guerin. This

was the charming way my life in Seoul was organized,

thanks to these good friends.