Most recently updated: September 29, 2008

Joan Grigsby (1891 –

1937) Part One: Family Background and Childhood

Anyone seeking all the essential information about the family origins and life of Joan

Rundall / Joan Grigsby / Joan Savell-Grigsby might expect to find it in the biography Dreamer in Five Lands

by Faith G. Norris (Philomath, Oregon: Drift Creek Press.1993). After all, the

author was her daughter, born in 1917, a university professor. Surely a reliable witness? So I thought.

However, it soon became clear that the contradictions which

I found existed between the account of Joan's family and her

childhood given by Faith Norris (based

largely, she says, on things her father told her in the years after Joan died) and the facts revealed by

certificates of birth, marriage and death as well as other sources were very considerable.

Finally, I wrote to Faith

Norris's own daughter in California, Joan Norris Boothe, who had

published Faith's book after her death, in the hope that she might be

able

to help. She replied that she had only learned the truth about her

mother's family origins a few weeks before I contacted her, through a

phone call from Philip Rundall, the son of Joan's brother, John Wingate

Rundall. He

had, amazingly, bought and read Dreamer in Five Lands at almost

the same time as I had. Born in 1947, he knew the whole family story

very well and had met all the members of Joan's generation in

his youth (some very briefly), but had never had any contact with Joan's daughter.

Bewildered by what he read in Faith's book, he felt that he should tell Joan Norris

Boothe the truth and finally traced her phone number, while I found her

mailing address.

She told him of my research,

and he emailed me with much additional information. This page is

therefore an attempt to record as accurately as possible the true

picture of Joan Rundall's family; the reason why she set about

creating a fictional family and childhood for herself is something we

can only guess at.

A brief summary of Joan's

origins begins the page containing the rest of the Joan Grigsby story.

Photos of Joan

Joan’s parents

and her childhood

A. Joan's Fantasy (As reported 50 years later by Faith Norris)

It

is a tribute to her mother’s story-telling skills that in 1982, Joan

Grigsby’s daughter and biographer, Faith Norris, a retired professor of

English literature, went on a pilgrimage across Scotland, all the way

to the Hebrides, so firmly she believed that her grandmother had

been a poor woman, Janet McLeod, born there in 1860, on the island of

Lewis. According to this story Janet learned nursing in Edinburgh, then

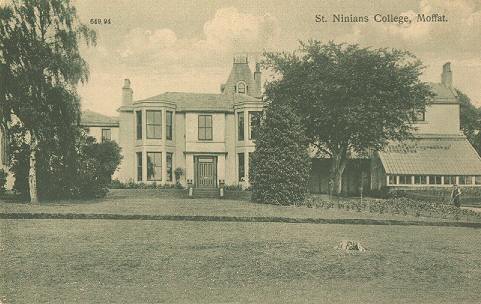

went on to become matron at a boys’ preparatory school, St. Ninian’s,

that had opened in the town of Moffat in 1879. She died of cancer in

1902 aged 43, leaving five children, the eldest being Joan. Joan’s

father, John Rundall, had come to St. Ninian’s as a teacher after

studying divinity (theology) at Cambridge, a fact never mentioned by

Joan and only discovered later, during the same journey in 1982.

Faith Norris believed that John Rundall’s father, Herman Rundall, had been

part of a large Jewish lace-making family which had moved to Brussels

in the 1840s to escape a pogrom in Poland. In the 1850s, when Belgium

in turn became a difficult place to be Jewish, the rest of the family

went to live in Germany, but Herman and his Belgian wife moved to

Edinburgh, continuing to make lace. The name the family had used in

Belgium had been Hirondelle, which they changed to Rundall once they

were in Scotland. They only had one son, John, who was baptized as an

Anglican at birth. If he went to teach in that obscure school rather

than enter the parish ministry in England, Faith Norris suggests, it

might have been because his features were strongly “Semitic” and in

those days anti-Jewish prejudices were very strong in upper-class

England. Herman Rundall had money, and he donated much of it to St.

Ninian’s. Perhaps because of that, John became the school’s headmaster.

Her story says that no one could say why he married the school’s

almost uneducated matron, Janet McLeod, or what his father thought of

it. Janet continued to work as matron after her marriage, while caring

for her five children. She died in 1902, when Joan was nine. Six months

later a bank crash almost ruined Herman and wiped out all John’s

savings. John died of a heart attack early in 1903, perhaps from the

shock of that. Joan stayed on at St. Ninian’s where her aunt, Fiona

McLeod, had taken her mother’s place as matron, sharing a room with her

and acting as her assistant.

Joan never attended regular school, but her grandfather had her learn

French, his wife’s language, and the French teacher made her memorize

French Romantic poetry. She told him she was trying to write poetry in

English, so he spoke to the school’s literature master, who met with

her occasionally and recommended what books she should read. Otherwise,

she could wander in the countryside, read what she wanted. She loved

walking in the countryside. On Joan’s eighteenth birthday, her

grandfather came to the school to decide on her future. She had never

studied music or art, so could not be a governess. The only option was

to go to a secretarial school in London to learn typing and shorthand.

She could live in the house of a friend of her father’s Cambridge days,

a married vicar, her grandfather would pay for her lodgings and studies.

That is a beautiful, romantic story, but almost none

of it is true.

B. The Facts from the official record and the family memory

The

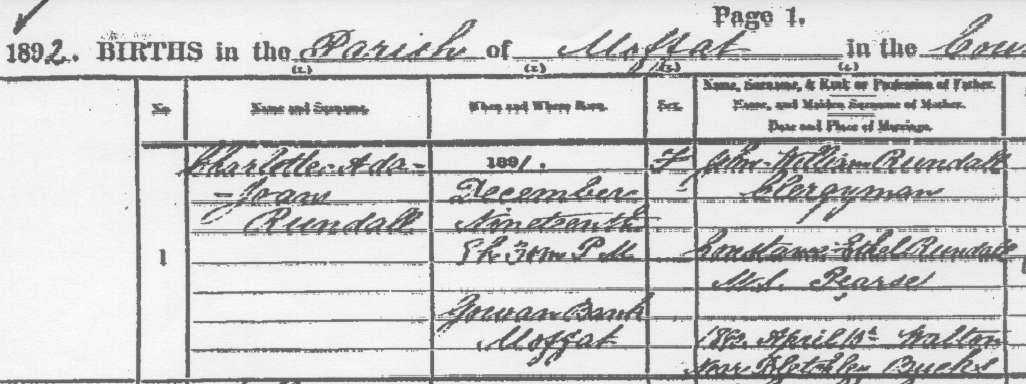

official Scottish records of births show that the woman known to us as

Joan Rundall (later Grigsby) received at birth the names Charlotte Ada

Joan. She was born at 9:30pm on December 19, 1891 at the house

called Gowan Bank, Moffat, Dumfriesshire (Scotland). Her father’s

name is given as John William Rundall (clergyman), but her mother’s

name was not “Janet McLeod” but Constance Ethel Rundall (born Pearse).

Their marriage date is given as April 10, 1890, in Walton near

Bletchley, Buckinghamshire (England).

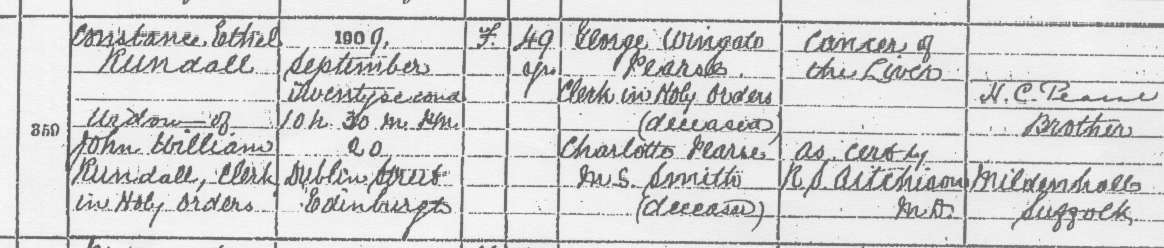

Another official Scottish record shows that John William Rundall’s

widow, Joan’s mother, Constance Ethel Rundall, died of cancer of the

liver on September 22, 1909, aged 49, not in 1901 as Faith Norris

believed. The names of her parents (Joan’s maternal grandparents) are

given on her death certificate as George Wingate Pearse (Clerk in Holy

Orders, deceased) and Charlotte Pearse (Smith, deceased). She died at

20 Dublin Street, Edinburgh and the death was reported by her brother H. C. Pearse of Mildenhall, Suffolk.

Joan’s father,

John William Rundall, was born in 1858 in

Dowlaispura, Madras, India, younger son of General Francis Hornblow

Rundall (Dec 22, 1823 - Sep 30, 1908), Royal Engineers, and Fanny Ada

Seton Burn (Rundall),

the daughter of Captain William Gardner Seton Burn (3rd Light Dragoons,

buried in Vizagapatam) who was married to a Miss Hewett of Duryyard,

Exeter. Her father was William Kellitt Hewett of Jamaica, who later

owned the very fine estate of Duryard, near Exeter. His funeral tablet

is in the aisle, behind the bishop's throne, in Exeter Cathedral. He

died 24/6/1812. Capt William's father was General Seton Burn, of the Indian

Army. Fanny Ada Seton Rundall died

13 October, 1889, at Thun, Switzerland, where she is also buried.

Originally the family's name seems to have been Seton and it claims a

link to

Christopher, married to Margaret, the sister of Robert the Bruce. General Francis Hornblow

Rundall was Inspector-General of Irrigation and Deputy Secretary to the

Government of India (1871-1874). The General's father was Lt Colonel Charles Rundall, Judge Advocate General of the Madras Army. He died, along with his daughter Henrietta, from

ptomaine poisoning (from almonds in soup!). Charles Rundall's father, John Rundall, was a ship's purser, in the Indian Navy.

John William's older brother Frank Montagu Rundall later followed in his

father’s footsteps, serving in India, Burma and China. Known as Montie, he married Rosa Bickersteth,

a daughter of the Bishop of Exeter. He became Colonel of the 4th Gurkha

Rifles and was awarded the C.B. the D.S.O. and the O.B.E.

The General

also had three daughters: Ada Henrietta (b. 1848 d. 1932). She

married Thomas Edmonstone Charles M.D. L.L.D. I.M.S. He was a professor

of mid-wifery (known as the Deliverer of Bengal! He later was Surgeon General and an

honorary physician to Queen Victoria and Edward VII). Katherine Laura (b.17.8.1849 d. 1920s. She married Lt. Col. Eric Fraser Smith-Neill). Mary Raby (b. 18.12.1860 d. 17.6.1935) Married Rev. Frank Wingate Pearse).

Joan's father, John William Rundall attended

Pembroke College, Cambridge, 1878 – 1882, (scholar, 1878); B.A. 1st

class Classical Tripos 1882. Deacon 1883, Priest 1884 (Glasgow and

Galloway). Assistant master, St. Ninian’s Preparatory School, Moffat

1882-7, headmaster 1887 – 1903. Curate-in-charge, Moffat, 1883-5,

assistant priest 1885 – 1903. He died on 31 July, 1903 in Falmouth,

Cornwall, after several months' illness.

On April 10, 1890, in Walton near

Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, the Rev. John William Rundall married Constance Ethel Pearse, the second daughter of the Rev. George

Wingate Pearse, the rector of Walton, Bucks.

George Wingate Pearse was Rector of Walton for nearly 50 years,

from 1850 until

1899; he died 26 December, 1899 and was buried at Walton. The Pearse

family comprised 13 children: Constance Ethel; George Wingate

Chernocke; Charles Bryant; Charles Edward; Francis Wingate; Mary

Louisa; Henry Thomas; Helen Lucy; Bertha Anna; Arthur Wingate; Mabel

Charlotte (a nurse at St. Bartholomew's Hopital, London, the person who reported the death of John William Rundall, who must have been caring for him in Falmouth); Stephen Wingate; Hugh Chernocke (who was present when his sister, Joan's mother, died). On

5 April 1891, the day of the 1891 census, W. Ro. Heneage (farmer)

and Mary L Heneage (farmer’s wife), were staying with the Rundalls at

St. Ninian's School, this farmer's wife being Mary Louisa, Constance's

sister.

Constance's mother's name was Charlotte Chernock Smith, whose father was the Reverend Boteler Chernock Smith. Constance's grandfather, George Pearse, was married to Elizabeth Jennings. He was a

magistrate, Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Bedfordshire and High Sheriff in

1822. They lived in Harlington House in Harlington, Bedfordshire

(Harlington Preparatory School, Rev Frank Wingate Pearse's school

in N. Wales, was clearly named after the house). Elizabeth was the Wingate

heiress, being the daughter of Anna Letitia Wingate, a descendant of

Francis Wingate, who imprisoned John Bunyan.

John William Rundall and his wife had six children: Charlotte Ada Joan (born December 19, 1891); Margaret Gertrude (born December 17, 1895); John Wingate (born July 15, 1898); Eleanor Constance (born February 14, 1897) and Francis Anthony (born November 5, 1899). Oddly, the name of the fictitious Jewish grandfather, Herman, emerges into fact as John Hermann Rundall on February 11, 1894, as the name of a baby born with the terrible condition known as spina difida, only to die on that date, his birth fifteen days earlier not being registered.

John Wingate Rundall became Lt. Colonel in

the 1st Gurkha Rifles. He retired from the Indian Army in 1947. His son writes: "He was

an able amateur artist; could sing well and he also could write well

(although nothing was published). He was a keen mountaineer and a

member of both the Alpine and Himalayan Clubs. After his mother died,

he was shipped off to live in Camberley with his aunt Ada Rundall

Edmonstone Charles. He hated this, finding it oppressive, and it put

him off religion for life. He was forced to go to church several times

on a Sunday and he described kicking against this by cutting up his

Sunday suit with a pair of scissors! Right to the end of his life, my

father harked back to his childhood among the Moffat hills, the place

where his lifelong love of mountains began. He would talk of tickling

for trout and describe The Old Mare's Tail, the waterfall, up in the

hills nearby (see the first of the photos in Dreamer). My father

regarded himself as a Scot and he could speak a bit of Gaelic. He was

very proud of Fanny Seton Burn's ancestry, which was Scots.".

Francis Anthony Rundall was a major in the Scots Guards, he married Beryl Day. Their son Jeremy (1931 - 1976) was the radio critic for the Sunday Times.

Eleanor Constance Rundall went to India, where she married. Her husband, Norman Bor became Director of the Forest Research Institute at Dehra Dhun. He was a world authority on Asian grasses and returned to England to

become Assistant Director of Kew Gardens. Eleanor came all the way from India to visit

Joan Grigsby in Vancouver a year or so before she died. She wrote The Adventures of a Botanist's Wife about their life in India

Margaret Gertude Rundall (known as Meg) married Donald Watson, a

rubber planter, out in Malaya. They had two daughters, Sheila, who died

in 2004, and Primrose (known as Dandy). When Meg was widowed, she was

housekeeper for her sister Eleanor and her husband Norman Bor, when

they returned to England (at Kew Gardens). Apparently Eleanor treated

her like a servant, which fits in with Faith's description of how both

Joan and Eleanor despised her, as girls. John Wingate Rundall's son

writes: I remember Meg as a tolerant and kind old lady.

It might be

noted that John William Rundall is reported to have been the author of

one book, Bridges,

published in 1890. His father, General Rundall, being an engineer, was

widely known and respected as an expert on canals and barrages and was

consulted in relations to the building of the Suez Canal and other

Egyptian projects.

General Francis Hornblow Rundall C.S.I., R.E. (Companion of the Star of India), the father of

John William Rundall, died at St. Ninian’s School on September 30,

1908, of a cerebral hemorrhage. The death was registered the next day

in Moffat by his son, Frank Montagu Rundall of 27 Princes Square,

London. The General was buried at Moffat. The Dictionary of

National Biography

(2nd edition) explains that the General (who

had retired back to England many years before) died “in the house of

the headmaster of St. Ninian’s, his son-in-law, the Rev. Francis

Wingate Pearse,” who later, 1929 – 1938, served as the rector of the

church in

Moffat as well as being the school's headmaster. John William's diary

of 1896 describes reading aloud to each other, his being taught to etch

by Constance, going on sketching trips with his father and other

members of the family in N. Wales when General F. H. Rundall was living

with the Pearses. It was a household where to write or create would be

encouraged.

Francis Wingate Pearse (son of the Rector of Walton and brother of Constance, Joan's mother) came to St. Ninian’s as headmaster in 1906,

from being headmaster of Harlington Preparatory School, Llanbedr, Merionethshire, in Wales (Bertie p.396).

There was a double alliance between the Rundalls and the Pearses;

Joan’s father, the Rev. John William Rundall, the General’s younger son, had

married Constance Ethel Pearse in 1890, while her brother the Rev. Francis

Wingate Pearse had married Mary Raby Rundall, one of General Rundall’s three daughters.

Francis Wingate Pearse died on June 29, 1939, in the Western General Hospital,

Edinburgh, aged 77, by heart failure provoked by a volvulus of the

pelvic colon. His residence at the time was 7 Montague Terrace,

Edinburgh. He is described as the widower of Mary Raby. His

father, the certificate says, was the Rev. George Wingate Pearse, his

mother Charlotte Chernocke Pearse (Smith). The 1901 English census

confirms that Mary Pearse had (like her other Rundall siblings) been

born in Madras. Under her full name, Mary Raby Wingate (Rundall) Pearse died on June 17,

1935 of a heart attack, aged 74.

Rosa Rundall (wife of Frank Montagu Rundall) wrote an account of

her son Montie's life for the benefit of his son, whom he never got to

see as he was killed within a day of his brother Lionel (author of The Ibex of Sha-Ping and other Himalayan Stories).

Joan's two 1st cousins, Montie and Lionel Rundall (both Gurkha

officers) were killed in 1914 at the battle of Festubert, as was

another 1st cousin, Alan Charles, son of aunt Ada Rundall Charles from

Camberley. The shock of these deaths still reverberates within the

family to this day.

Philip Rundall, an artist, the son of John Wingate Rundall,

Joan's brother, writes: "My father worshipped his mother; he regularly

talked to me about her (although we have no photo of her). He described

her as a saint, an incredibly tolerant woman. I have a history of St

Ninian's in which she is described as being unusual as she related

kindly to the domestic staff. I read a letter in Canada, in which she

describes Joanie as being an extraordinary support after John William

died. Incidentally she wrote to the general asking for financial

support to keep the school afloat. The school was regarded as one of

the two top preparatory schools in Scotland. I have John William's

diary of 1896 in which he describes the slow process of buying the

school from Dowding, the then Head. Dowding's son was Lord Dowding, the

head of the Royal Airforce during World War 2. General Rundall became

the Inspector General for Irrigation for the Gov. of India and was

Colonel Commandant of the Royal Engineers. The graves of baby Herman,

General Rundall and Mary Pearse (although she is named Rundall, not

Pearse, on the headstone) are all in the beautiful Moffat

cemetry. Eleanor, the sister Joan was closest to, was my

godmother.

(The fullest single published source of information about Joan’s father,

John William Rundall, and her uncle, is to be found in David M. Bertie’s Scottish

Episcopal Clergy 1689 – 2000 (Continuum International Publishing Group,

2001).)

C. The riddle

There

are, then, two almost completely different accounts of Joan Grigsby’s

parents, that related by Joan to her husband (and to her daughter, to

some degree) and that which we can reconstruct from the official

record. Faith Norris makes it clear (p.17) that she first heard the

story of the Jewish grandfather, Herman Rundall, from her father after her mother’s

death, between 1937 and 1947, when her father died. She implies that the story of Herman

Rundall’s gifts to the school having perhaps been the reason why Joan’s

father became headmaster was also her father’s, as also the account of

her father’s “strongly marked Jewish features.”

She

says that her father first learned of Joan’s Jewish ancestry five years

after their marriage. Elsewhere she indicates that the revelation of

this “truth” was the result of Joan’s conversion to Catholicism, and

that she wrote it to her husband, then in France, at the command of a

priest. There is only one indication that her mother ever told her

anything about her childhood; Faith Norris mentions “what my mother

called her mother’s ‘Gaelic-haunted Highland lilt’.” She seems to be

saying that she heard those words directly.

The essential facts of Joan’s father’s adult identity are preserved in

her own account : he was an Anglican (i.e. in Scotland

“Episcopalian”) priest who had come to St. Ninian’s School as a teacher

and had become headmaster of the school, a position he held until his

death. The year (though not the month) of his death is correct. Her

grandparents, Faith Grigsby correctly says, had five children (p.17),

she names two boys as “John and Tony” (p.18) as well as Joan's sisters

Margaret and Eleanor.

The true story after 1901

John William Rundall was not simply the headmaster of St. Ninian's, he

was its owner, having bought it from the original owners. On his death,

it became his wife's property. Philip Rundall writes:

"Immediately behind the school is another largish house called Wykeham

Lodge. This I believe may be where Constance lived with Joan. In the

history of the school it says, after her husband's death, 'Mrs Rundall,

however, moving to a nearby house, remained the owner of the property,

and even after she died in 1910 [really 1909], leaving two young sons

still as pupils at the school, she bequeathed it not to Frank, who, had

already been its headmaster for four years, but to her brother Hugh,

who, however, soon left to be ordained at Ely, and in 1911 conveyed the

property and the school to his brother Frank in consideration of the

paying-off of debts which, unsurprisingly in view of the declining

numbers, were by now substantial.'

The

school's history has a section entitled Interregnum: 1903 - 1906

: 'It is not surprising that on the sudden death of Rundall, at

only 44 years of age, a difficult period should have followed. He left

the school to his widow (nee Constance Pearse), and she was in nominal

command for a while, assisted by her brother Hugh Chernocke Pearse. Nor

is it at all surprising that in this unsettled situation numbers

declined still further, till in the Spring term of 1906 there were only

15 boys in the school, which must have been on the verge of closure,

when another brother, and the second dominating figure in the School's

history, came from Wales to the rescue.'

Philip

Rundall writes: "My father (John Wingate Rundall, Joan's brother)

worshipped his mother; he regularly talked to me about her (although we

have no photo of her). He described her as a saint, an incredibly

tolerant woman. I have a history of St Ninian's in which she is

described as being unusual as she related kindly to the domestic staff.

I read a letter in Canada, in which she describes Joanie as being an

extraordinary support after John William died. Incidentally she wrote

to the general asking for financial support to keep the school afloat.

The school was regarded as one of the two top preparatory schools in

Scotland. I have John William's diary of 1896 in which he describes the

slow process of buying the school from Dowding, the then

Head." The school buildings are now a home for elderly

ex-RAF men, called Dowding House, after the WW2 Chief of the Royal

Airforce, Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, the son of the school's

founder.

Faith

Norris says (p.19) that after Joan’s father died in 1903, her brothers

remained as boarders at St. Ninian’s while the two girls (who were aged

8 and 6 in 1903) went to live with “Herman Rundall and his wife” in

Edinburgh. On p.38 she says that in 1916 Margaret and Eleanor had

finished their education at George Watson’s Ladies College in Edinburgh

and both came to London, Margaret to train for the Women’s Army Corps

and Eleanor to study at a home economics institute. This raises the

vexed question of Joan’s own education. Primary education had been

compulsory in Scotland since 1872. But in 1903 Joan was nearly 12,

while Margaret and Eleanor were still small children. There seems no

reason to suppose that in fact any of the children left their mother’s

side before she died in 1909. By that time, their uncle was headmaster

of St. Ninian’s and might well have taken decisions for their ongoing

education and careers. For Joan, already aged nearly 12 in July 1903

when her father died, there was probably nowhere she could go for

secondary education and the story that she received informal classes

from teachers at St. Ninian’s might well be true.

Joan Rundall apparently came to London in 1910 and she met Arthur early

in 1912. Since Faith Norris had ample opportunity to talk with her

father in the years after Joan’s death, we can assume that the

narrative from that point is fairly reliable. It seems that Joan

invented at least part of her story about her family at that moment. We

know that her mother died in September 1909, but Arthur clearly

believed she had died years earlier, before her father. Her paternal

grandfather was not in fact alive to provide for her as Herman the Jew

was later said to have done, but her uncle the headmaster of St.

Ninian’s might well have felt obliged to do so. The London clergyman to

whom she was sent might have been, Faith says, a university friend of

her father’s and Francis Wingate Pearse

might well have had such a friend, for even though he studied at

Trinity College, Dublin, (B.A. and M.A.) he was ordained in the English

diocese of Rochester. But the 1911 census shows that in fact the

clergyman was no other than her uncle, Hugh Chernocke Pearse, still

unmarried at 42.

One thing is clear. The fantastic stories that Joan told about her

father’s family and her mother served to erase completely one essential

fact: her parents were both utterly English, she had no immediate Scots blood.

Her father was the son of an English general, born in India into a

family that was traditionally part of the colonial establishment while her mother was the daughter of an

English rector. Something in Joan might have rebelled for some hidden reason. Faith

Norris in the opening lines of her memoir testifies that to her dying

breath Joan affirmed her Scottishness by her accent, by singing the

song of all Scottish exiles, and dreaming of a return to the Highlands

and the Hebrides that, in fact, she had never seen.

The Celtic poetess Fiona MacLeod

Joan created an archetypal Hebridean mother for herself, her voice

at least still touched by the Gaelic, deeply rooted in Scotland’s

traditions, poor and uneducated. She called her Janet McLeod, a common

enough name. Curiously and perhaps significantly, the fictional

aunt Fiona McLeod, with whom she claims she lived and worked at St.

Ninian’s "after her parents’ death," has the same name as a Scottish poet

who might well have had an influence on Joan’s writing. Her name usually spelled Fiona MacLeod, she was considered a Celtic

visionary and romantic in the late nineteenth century, her works being

read together with the poems of W.B. Yeats. Readers of the period were

enchanted by the marvelous weaving of folklore, myth, vision, and

personal observation in her prose and poetry. It caused a great scandal

when it was revealed in 1905 that the works attributed to Fiona MacLeod

had in fact been written by the male Scottish poet and writer William

Sharp. The fictional female pseudonym, and the Celtic identity might

both have spoken strongly to the dreamer awakening within Joan Rundall.

See the text by Dr. Robert Irvine where he writes:

Arnold

once wrote: "no doubt the sensibility of the Celtic nature, its nervous

exaltation, have something feminine in them, and the Celt is thus

particularly disposed to feel the spell of the feminine idiosyncrasy;

he has an affinity to it; he is not far from its secret." What links

the Celtic to the feminine is their common marginality to a public

culture understood as predominantly masculine. After all, the qualities

Arnold accords the Anglo-Saxon ("steadiness", practicality,

rationality) are usually gendered masculine, the qualities of the Celt

(sensitivity, emotionality, imagination) are usually gendered feminine.

The Celt, one might say, seems designed to be, not so much the partner

of the Anglo-Saxon in their joint Imperial project, as his wife. By

adopting a female persona Sharp is assimilating himself as author to

the celtic world that his fictions portray. (. . . ) putting women at

their centre, with a fair degree of authority, but as exotic creatures,

as inhabitants par excellence of that "alien" celtic world Sharp is

setting out to explore. Hence the feminine pseudonym: this exotic world

is one to which women might have privileged imaginative access.”

At

some point Joan also created an archetypal rich, European Jewish

grandfather with a Belgian wife (to talk with whom, she claimed, she

had learned French). There was, then, only one person she could not

recreate: her father. The clergyman and his wife to whom she was sent

in London, and in whose house she met Arthur and his mother, would

obviously have been told the identity of her father, the deceased

clergyman and headmaster. Even the year of his death was clearly fixed

in the family memory, and the cause, too, for he did indeed die of

heart problems.

Her father's

death certificate says he suffered from

Endocarditis for 4 months, General Oedema for 1 month, and that then

affected his lungs for the last 3 days. Faith talks of two heart

attacks. The person who reported the death was a nurse, Mabel Pearse,

his

sister-in-law (obviously an as yet unmarried sister of his wife) but it is not

possible to know why he was in Cornwall though the mild climate might

have been thought good for someone with a weak constitution. His wife

would have been running the school in his place, presumably.

Joan

Rundall was certainly a rebel when possible; even her conversion to

Catholicism might be seen as a rejection of her parents’ and

grandparents’ Anglicanism. Her first

poems were published in a magazine of the Labour Party. She was always

aspiring to a better life elsewhere, she sympathized as she could with

the plight of the Koreans, and when they had to leave Asia, she clearly

did not consider a return to England, where she still had family, for

Francis Wingate Pearse served as priest in Moffat until he retired in

1938. Instead, she insisted on Vancouver because it had looked so

beautiful as they left for Japan.

It seems unlikely that we shall ever know if her departure from Moffat

after her mother’s death was marked by some traumatic event that

made her want to reject her mother’s and father’s family’s identities

completely. It seems unlikely that wanting to be a Scot and an outsider

would provide a strong enough motivation for a whole lifetime, however

short, of silence. For it is the Pearse family and the Rundall family

that she denies, substituting the McLeods and the Hirondelles for them.

Now ‘hirondelle’ is the French word for a skylark, or just a ‘lark,’

though not in the joking sense, but perhaps that was her little joke?

This page is already too long! For the story of her marriage and journeys to Canada, Japan, Korea, and back to Canada, see Part Two