Life and Times | Shorter Works | Troilus and Criseyde

| The Canterbury Tales

(general introduction) | Summaries of the Canterbury Tales

: Fragments I, II, III,

IV, V, VI, VII,

VIII, IX,

X. | Reading the Canterbury

Tales | Longer introductions to certain Tales: The General Prologue; The Miller's Tale; The

Nun's Priest's Tale; The

Pardoner's Prologue and Tale; The

Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale. An annotated text

of the Wife of Bath's Prologue

and Tale.

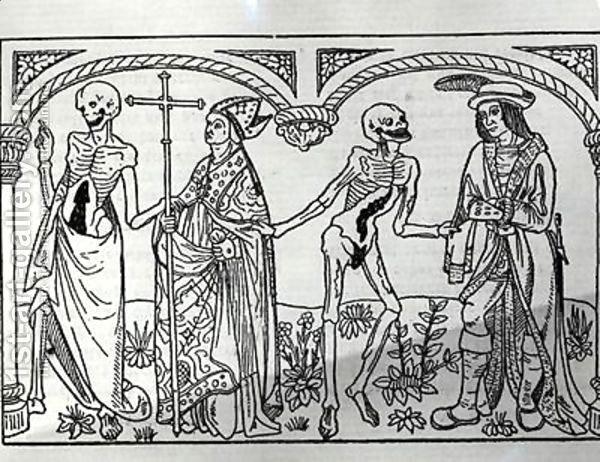

Society in Chaucer's England was divided into 'orders': those who

fight, those who labor and those who pray, the nobles, the

peasants and the clergy.

England was ruled by kings and lords, the most powerful of

whom were known as 'barons' with huge lands and almost royal

power. Most people were 'commoners' who lived in villages and

worked land that belonged to lords and 'gentlemen' (noblemen).

Gentlemen (gentry) and higher aristocrats were 'noble' while the

rest were 'commoners' although 'yeomen' commoners might also own

land. Land was seen as the main form of wealth, but the 'farmers'

(peasants) working the land usually paid rent in kind

(agricultural products) so that the land-owning lords often had

little ready money. Peasnats were also allowed to work 'common

land' where they pastured their own animals and planted their own

crops without having to pay rent.

|

|

|

|

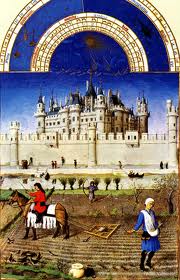

The towns and cities were inhabited by free citizens, a mixture

of merchants and poorer working people, with a town council

presided by an annually chosen mayor with no special powers. Many

merchants were the younger sons of landowners who wanted to earn a

living. There was no professional army; aristocrats might practice

martial skills and would be required to raise and lead a troop of

soldiers from among their male tenants if the king and Parliament

decided to fight a war. The sons of noblemen were termed squires

and they might either prepare to become mounted soldiers

('knights') or courtiers (administrators), or both.

|

|

|

|

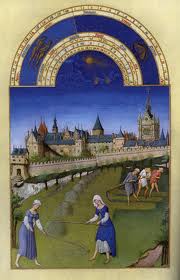

The royal court was the seat of real power, and of sophisticated

culture. The king was required to consult his 'Privy Council" on

most decisions. Parliament was already divided into two 'houses':

Lords and Commons. The higher lords who were eldest sons

automatically became members of the House of Lords when their

fathers died. The church's Bishops were also members of the House

of Lords. The members of the House of Commons were elected by the

richer (house-owning / land-owning) citizens in boroughs across

the country each year. Originally Parliament was an advisory body

but by Chaucer's time it was agreed that a king could not make new

laws, raise an army or levy taxes without Parliament's consent,

since the Commons represented the people with money who would have

to pay taxes and keep the laws. Chaucer became a Member of

Parliament briefly.

|

|

|

|

The Church owned much land. The country was divided into dioceses

ruled by bishops, there being 2 archbishops in Canterbury and

York. Each diocese was divided into small parishes with a rector

in charge and other priests helping. The people had to pay

'tithes' to the parish to support the priests. There was only one

Church, the Catholic Church, although each national church was

fairly independent and bishops were often appointed by the king

rather than the Pope in Rome. In addition, there were many

monasteries, away from the towns, with land, tenant peasants to

work the land, while the monks prayed and studied. From the 13th

century there were also many groups of Friars belonging to new

groups founded by St Francis, St Dominic, etc who lived in the

towns, ran their own churches, 'begged' for money from the

ordinary people and competed with the ordinary priests. Priests

belonged to the 'clergy'; the 'clerk' was someone who had learned

to read and write, and had studied, but many clerks did not become

priests, instead they went to work as secretaries in the houses of

powerful lords. In England there were only two 'schools'

(universities), at Oxford and Cambridge; young lords and other

wishing to learn about law studied at the 'Inns of Court' in

London. Chaucer seems to have learned to read and write as a page

serving in the royal palaces, without any formal education.

|

|

|

Chaucer is mentioned no less than 493 times in contemporary documents, mostly lists of money paid out to people serving the king or other powerful figures. Through them we know many details about his career in royal and government service. The literary works played no apparent part in this public career and there is no indication in the court or public records of his writing activities. Yet there is no serious doubt that in the course of his busy working life, Geoffrey Chaucer found time to translate and write the various works that make him the first recognizable named "author" of England. The many documentary records mean that we can follow his life in far greater detail than, for example, that of Shakespeare. They establish the context in which he moved, although they shed little or no direct light on the works he wrote.

Chaucer's father, John Chaucer, occasionally held positions in the royal administration, but he was first and foremost a wine-merchant in London, an important member of the business (merchant) community. Geoffrey Chaucer's mother's name was Alice. Geoffrey, probably their only son, was born some time around 1340. In 1386 he is noted in a legal record as being 'del age de xl ans et plus, armeez par xxvii ans' (of the age of forty years and more, bearing arms for twenty-seven years) and the years 1342-3 are popularly accepted as being the most probable years for his birth.

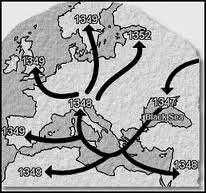

In 1348-9 Chaucer and his parents were fortunate to escape

infection during the Black Death. The history of this

pandemic begins with the arrival from the Middle East of a boat

full of dying sailors in Sicily in October 1347. The plague,

spread mainly by the fleas carried by infected rats, arrived in

coastal towns of England in June 1348, and reached London early in

1349.

|

|

|

Within eight months, some 2 million of England's 5 million

inhabitants were dead. Some villages lost all their inhabitants,

in many places more than half died, yet remarkably enough the

normal functioning of society was not seriously interrupted. After

this, there were regular outbreaks of the plague during Chaucer's

lifetime and for centuries after, until the last Great Plague

ravaged London in 1665. Most of Alice Chaucer's family died in the

Black Death.

Records from 1357 show that Geoffrey Chaucer was already serving as a page in the household of the young Prince Lionel, later Earl of Ulster and Duke of Clarence (1338-68), one of the sons of king Edward III. In 1359 Chaucer was given the right to bear arms and fight for the king and his social title would then have been valettus or yeoman. He went to France that year in a small company led by Prince Lionel. There he was taken prisoner and had to be ransomed early in 1360. He returned to France briefly later the same year. After this there is no record mentioning him for several years, except a possible indication of a visit to Spain in 1366. Prince Lionel was in Ireland during these years but Chaucer may well have gone into the king's service instead of following him there.

By 1366 he had married Philippa de Roet, a maid to Edward III's Queen Philippa. Katherine de Roet, Chaucer's sister- in-law, was for many years the mistress, later the third wife, of the powerful magnate John of Gaunt (1340-99), another son of King Edward. Records show that by 1367 Chaucer was serving the king as a Valet, but now with the social rank of esquire. He was never knighted.

We have no indication of when Chaucer began to write but it seems

likely that among his first experiments was an attempt to

translate a few parts of the 13th-century French love-allegory le

Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose). All that

exists of this translation are a few fragments, and not all those

are certainly by Chaucer, but certainly the work itself exercised

a profound influence on him. Oddly enough, Chaucer almost never

uses the allegorical personifications that characterize the Romance

of the Rose in his own writing. His first work seems to have

been The Book of the Duchess, provoked by the death

of John of Gaunt's wife Blanche, in 1368.

The royal accounts give an interesting glimpse of the ways Chaucer was paid for his services. For example, in 1368 he was given a license to travel from Dover to France with two horses. With that he received twenty shillings in English money for his expenses as well as ten pounds in foreign exchange. In 1374 the king awarded him one pitcher (about five liters) of wine each day for life; a few years later he was able to have this changed to a regular money payment. In 1377 he received forty shillings for winter and summer robes. Later he received regular annuities, but the monthly salaries normal today were unknown in his time.

He made a number of journeys abroad. It is possible, but very unlikely, that he attended the marriage of Prince Lionel in Milan in 1368. Poor Prince Lionel died while still in Italy, only a few months after his wedding. Certainly Chaucer was in Italy a few years later. records show that in 1372-3 he went to Genoa and then on to Florence on official business. Chaucer may well have learned Italian before this, from Italian merchants doing business with his father in his childhood.

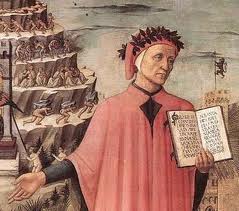

The Italy he visited was not a nation-state but a patchwork of often very sophisticated city-states, each with its own ruler. It was a place of intense cultural activity. The great painter Giotto had already finished his work and died forty years before, not long after Dante; the first great steps in renaissance humanism had already been taken; poetry was immensely valued in society. When Chaucer arrived for his first visit, Petrarch (1304-74) was just completing the final version of his Canzoniere, Boccaccio (1313- 75) too was still active. Both were by then very famous old men and it is not at all likely that Chaucer could have met either of them. There were some great libraries in Italy but we do not know if he would have been allowed to view them. He was only a rather junior foreign envoy, after all.

Chaucer stayed some three months in Italy, but we have no

information on his activities. Florence was the centre of the cult

of Dante (1265-1321) and

a year later a series of lectures on Dante was given there by

Boccaccio. Probably it was on this first visit that Chaucer

obtained a copy of Dante's works.

|

|

|

In 1374 Chaucer was made controller of wool customs in London, a

difficult and time-consuming job, which meant he no longer had to

be present regularly at court. He may have realized that political

tensions were brewing between court and Parliament and wanted to

find a quiet job away from trouble. In the same year he received

the right to live rent-free in accommodation on top of the city

gate known as Aldgate.

It seems likely that it was in or after 1374 that he composed The House of Fame, which shows strong influence from Dante but owes nothing to Boccaccio, of whose works Chaucer seems only to have learned on his second visit to Italy. This odd work is preserved, like the Book of the Duchess, in only a few copies; clearly Chaucer had not yet become a popular writer. The dating is made possible by references to his customs work in lines 652-5.

King Edward III died in 1377, less than a year after the death of

his eldest son, Edward the Black Prince. The Black Prince's son

became King Richard II at the age of ten. In 1378 Chaucer

again went on royal service to France and to northern Italy,

as the junior member of an embassy to Bernabo Visconti, the Lord

of Milan whom he later introduced into the Monk's Tale's list of

great falls. Visconti was murdered in 1385.

|

|

|

He almost certainly brought back from this visit copies of Boccaccio's Filostrato, Teseida, and probably other works. Chaucer uses the Teseida in the fragment Anelida and Arcite, The Parliament of Fowls, Troilus and Criseyde, as well as the Knight's Tale. The Filostrato is the basis for Troilus. The two youthful works by Boccaccio were particularly congenial to Chaucer, who obviously felt a deep affinity with the way they were composed, and adapted them in remarkably free and creative ways. It is not possible to decide whether Chaucer knew the Decameron directly, although its use of a framing device is thought to have inspired the structure of the Canterbury Tales.

Perhaps soon after his return from Italy, he wrote The Parliament of Fowls. This work is preserved in fourteen manuscripts, and many more have been lost; it was obviously far more widely known than the previous two works. Like them, it too is in the popular form of a dream-vision, inspired by a widely- read Latin classic, Cicero's Dream of Scipio from the commentary of Macrobius. This is precisely the book that Chaucer picks up at the start of the poem, before falling asleep and beginning to dream.

In 1381, London was the main focus of the so-called 'Peasants' Revolt'. This complex event was the climax of a number of different social processes and not all the people involved were peasants. It certainly reflected a widespread wish for freedom from older kinds of administrative control. Since so many villagers had died in the Black Death, labourers' wages had risen and the Parliament had several times tried to make laws reducing farm workers' wages. The imposition of new taxes, a poll tax in particular, in 1377, 1379, and 1380, increased resentment to breaking point. In London too, there were many discontented people.

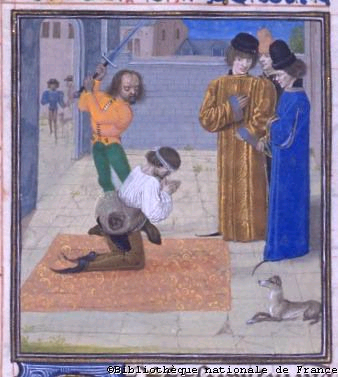

In June 1381, the rebels from Kent reached London, claiming they wanted to obtain justice from the young king Richard II, whom they idolized. They plundered the city, burning John of Gaunt's Savoy Palace in revenge for his role in making the new taxes. They dragged a group of Flemish immigrants from a church and massacred them for taking work from Londoners. Finally, they entered the Tower of London and murdered the Archbishop of Canterbury.

King Richard agreed to meet the rebels' leaders at Smithfield and

showed himself understanding. Then, while they were talking, the

mayor of London suddenly struck down Wat Tyler, the main

leader of the revolt, and in the confusion the other main figures

were arrested. Many were later executed. There is no indication

that Chaucer played any role in these events, although he does

mention the leader from Essex, Jack Straw, in the Nun's

Priest's Tale. Some of the rebels were idealists motivated

by a kind of religious egalitarianism and quoting from an early

version of Piers Plowman,

but Chaucer probably saw them as a lawless rabble.

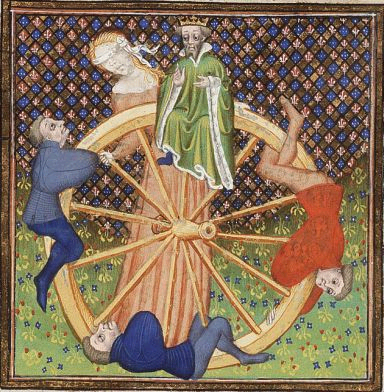

Almost certainly, Chaucer began to work on adapting the works by Boccaccio he had brought back from Italy soon after his return. Later, in 1386-7, he began to write The Legend of Good Women and in the Prologue to that unfinished work, Alceste defends Chaucer against the reproaches of the god of Love who is angry that he translated the Roman de la Rose and wrote Troilus, two works that give a negative picture of women (later parts of the Roman are fiercely anti-feminist). Alceste replies that Chaucer has written other works that encourage people to serve and praise Love. She names the House of Fame, 'the Deeth of Blaunche the Duchesse', the Parliament of Fowls, and a work she calls The Love of Palamon and Arcite. It is generally assumed that this last work is the adaptation of the Teseida that we know as the Knight's Tale in the Canterbury Tales.It would seem that Chaucer wrote that before or at the same time as he began work on Troilus and Criseyde, but did not distribute it before making it part of the Tales.

Troilus and Criseyde was written during the years

1381-6 and was the first of Chaucer's works to be widely admired.

It and the Knight's Tale are both deeply marked by the influence

of Boethius's Consolation

of Philosophy which he was perhaps translating at the

time. Alceste, in her defence of Chaucer, later mentions that he

translated Boece, the standard medieval name for Boethius.

Chaucer mentions the work with some pride in the 'Retracciouns' at

the end of the Parson's Tale. His translation is entirely

in prose, following the model of Jean de Meun's French version

which he used. In view of the strong Boethian influence on Troilus

and the Knight's Tale, it seems fair to assume that

Chaucer was translating Boethius at the same time as he was

writing them. Perhaps he also wrote the short poems on Boethian

themes at this time: The Former Age, Fortune, Truth,

Gentilesse, and Lak of Stedfastnesse.

Thus, during the 1380s, Chaucer became widely known among the

literary circles of London, and around him we find a few quite

powerful men who seem to have constituted a 'Chaucer Circle':

Sir Lewis Clifford (friend of the French poets Deschamps and Oton

de Granson), Sir Richard Stury (friend of the French chronicler

Froissart); Sir John Montagu (admired as a poet by the great

French poet Christine de Pisan); and John Clanvowe, who later

wrote the first 'Chaucerian' poem The Book of Cupid. To these

should be added Henry Scogan, Thomas Hoccleve, Thomas Usk, John

Gower, and Ralph Strode.

|

|

At the same time, Chaucer was active in society. In 1386 he was

elected as Member of Parliament for Kent and at the end of the

year he resigned from the position as controller of the wool

custom. In 1385 he had become a member of the commission of the

peace for Kent, the board of magistrates responsible for judging

people charged with small offences at sessions held a few times

each year. Chaucer seems to have left London at this time and gone

to live in Kent. He may have realized that trouble was coming. In

1386-9 there was a fierce campaign by Parliament against

corruption in the royal household, culminating in the 'Merciless Parliament' of 1388,

when a number of people in positions similar to Chaucer's were

executed.

By refusing to take sides and by knowing when to withdraw, Chaucer

survived with reputation intact. He became clerk of the king's

works in July 1389, only a few months after King Richard had taken

over the running of national business for himself. This was a very

challenging position. He had to oversee building and repairs on

the properties belonging to the king, paying wages, obtaining

materials, recruiting workmen. During Chaucer's time in office,

Henry Yevele was building the

nave of Westminster Abbey. The main work overseen

by Chaucer was the construction of a new wharf at the Tower of

London, as well as the new roof of Westminster Hall. He also had to oversee the

building of 'lists' for a royal tournament at Smithfield in 1390.

These humble wooden lists must have contrasted sharply in his mind

with the magnificent constructions he had described in such detail

in the Knight's Tale. He lost his job rather suddenly in

1391. 1391 is also the year used as a model in his Treatise on the

Astrolabe, which seems to have been written at this time

for his son or god-son.

|

|

|

Chaucer probably went on living in Kent during this time. This

was not necessarily far from London. There is some possibility

that his home was in Greenwich, only a few miles down the Thames

from London Bridge. These were now the years in which he did most

of the work on the Canterbury Tales, still far from

complete at his death. A considerable number of the separate Tales

were undoubtedly completed before this, of course. The tale of

Saint Cecilia, the story of Melibee, the tragedies told in the Monk's

Tale, perhaps even the treatise on sin given to the Parson,

must date from earlier stages in Chaucer's career.

|

|

The records seem to show Chaucer having problems with small debts during the 1390s. His income was irregular, but there are several records of new grants and some generous gifts, including an annual barrel of wine from the king in 1397. At some point he seems to have been named deputy forester for the forest of North Petherton in Somerset. He moved back into London in 1398, and took a lease on a house in Westminster in late 1399.

He was therefore well placed to experience the dramatic events of Richard's downfall. Richard had been trying to secure peace with France, and this did not please some of the most powerful lords, including his uncle the Earl of Gloucester, the youngest son of Edward III, the Earl of Arundel, and the Earl of Northumberland, who had public opinion on their side. In 1396, in a peace-making move, Richard married Isabella, the daughter of the king of France, to replace his first queen, Anne, who died in 1394.

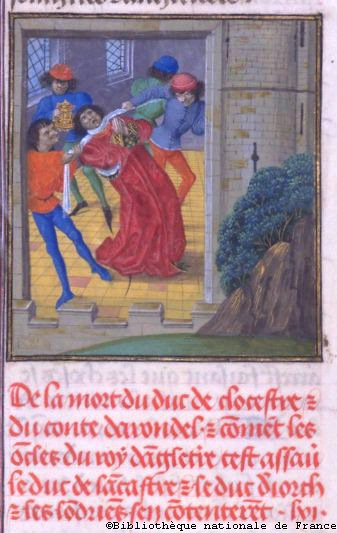

In 1397 Richard had Gloucester and others arrested. Gloucester

was sent to France, where he was secretly murdered by Mowbray

(Duke of Nottingham). Others too were exiled or executed. In

January 1398 Richard made Parliament grant him an income for life,

and forced various counties to pay him large sums in fines and

loans. It seemed to some that the king wanted to be tyrant of

England and to this end he appointed a Council where no one would

oppose him. He surrounded himself with favourites and lived in

greater luxury than any English king had ever known before.

Richard was a great patron of the arts. When Mowbray and John of

Gaunt's son the duke of Hereford (Henry Bolingbroke) accused each

other of treason (both knew about the murder of Gloucester),

Richard organized a formal trial by combat in September 1398. As

they prepared to fight according to the rules of chivalry

governing disputes between peers, Richard abruptly stopped the

proceedings and exiled them both. In February 1399 John of Gaunt

died. In March Richard confiscated all Gaunt's properties that he

had earlier promised Bolingbroke should inherit normally,

declaring him banished for ever. Richard then left for a campaign

in Ireland; he had no adviser who dared to tell him he was acting

very foolishly. In late June Bolingbroke landed in the north of

England and many of the powerful lords joined with him. At first

he claimed to have come only for his lawful inheritance. The king

returned from Ireland to find that he had no army left and was

obliged to trust the promises made by the Earl of Northumberland.

After being arrested, on September 30 Richard abdicated, and on

October 13 Bolingbroke was crowned King Henry IV. Richard

was murdered in prison early in 1400.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Henry IV quite quickly confirmed Chaucer in his positions and regular income but no money appeared, and he needed money for his new house in the garden at the east end of Westminster Abbey. He therefore sent the new king a poem, The Complaint to his Purse, which he may have written before. Whether because of it or not, he was paid soon after but did not collect the payment himself. Perhaps he was sick? Chaucer is traditionally said to have died on 25 October 1400 and was buried in the south transept of Westminster Abbey. A monument to him was erected during the reign of Mary Tudor in 1556, starting the tradition of "Poet's Corner."

Chaucer was not, then, a professional writer but a courtier and a civil servant. It is not possible to know what was the relationship between his writing and his public life. Perhaps at first it offered him ways to make himself noticed by the powerful people on whom he depended for work and income? Or was it mainly a private compulsion, yielding works shared with only a few like-minded friends?

Probably only five percent of the people in Chaucer's England

could read at all, and many of them had no chance to read literary

works. It seems to have been the practice, even at the court, for

one person to read aloud from a manuscript book to a listening

audience; there is a painting in one manuscript of Chaucer doing

this himself, before the gathered court, but this scene is not a

realistic portrayal. One vital characteristic of Chaucer's art is

the way it plays with the contrasts between oral story-telling and

written literature.

Chaucer's earliest works may be termed "occasional poetry", if we accept that the Book of the Duchess was written to console John of Gaunt on the death of his wife Blanche in 1369, and if the Parliament of Fowls was written to mark the marriage of Richard II in 1382. But nobody has found an occasion to explain the writing of the House of Fame, and none of these three works corresponds to a conventional kind of occasional poem.

In the Book of the Duchess (1334 octosyllabic lines), the love-sick narrator falls asleep as he reads the sad love story (from Ovid) of Ceix and Alcyone, and dreams he is in bed early in the morning, then out hunting. He follows a dog down a path, where he finds a knight dressed in black lamenting the loss of his lady; the narrator forces the knight to tell how good and beautiful she was, and at last obliges him to admit that she is dead. The other hunters reappear, a bell strikes, and the dreamer awakes with his book still in his hand.

The Parliament of Fowls (699 lines in rhyme-royal, seven- line stanzas rhyming ababbcc) begins with the narrator reading the Somnium Scipionis and reflecting on the nature of love; he falls asleep and the protagonist of Cicero's book, Africanus, leads him into a garden which is an illustration of the themes of the book. They reach the temple of Venus, which is full of emblems of the power and sorrows of love; finally, in a garden similar to that of the Romance of the Rose, the birds are gathered before the goddess Nature for a debate about the problem of a female eagle loved by three males. Lower class birds offer un-poetic, practical solutions to this impossible problem, and the debate is adjourned for a year so that the female can reflect quietly. The noise the birds make as they disperse wakens the narrator, who picks up other books in search of something he cannot find.

The House of Fame (2158 octosyllabic lines) consists of three books, and is incomplete. There is a Prologue on dreams and an invocation to Sleep; Book I tells of the dreamer's visit to the Temple of Glass where he finds images suggested by Book IV and other parts of Virgil's Aeneid. In Book II he is seized by a talkative eagle and carried up into the House of Fame in the heavens where he sees, during his visit in Book III, images of famous writers; in particular he sees how arbitrary Fame is. Beside the House of Fame he sees the Labyrinth, representing the confused complexity of human existence, with all kinds of false tidings carried by shipmen and pilgrims. An un-named figure "of great authority" appears and the poems stops short.

To these three works should be added two other titles: Anelida and Arcite, a strange fragment of a love story, and the incomplete Legend of Good Women. The Legend begins with a Prologue which exists in two versions, then uses the decasyllabic couplets so familiar freom the Canterbury Tales to tell nine stories of famous women: Cleopatra, Thisbe, Dido, Hypsipyle and Medea, Lucrece, Ariadne, Philomela, Phyllis, and Hypermnestra.

The Legend of Good Women, of which twelve manuscripts survive, breaks off in mid-sentence and there has been much debate as to whether Chaucer wrote more. In the 'Retracciouns' he calls it 'the book of the XXV. Ladies' and this same title was used by someone writing between 1406 and 1413. In the Introduction to his Tale, the Man of Law, praising Chaucer, refers to is as a 'large volume' and lists sixteen heroines although his list omits some whose tales survive. It seems better to think that by some accident much of the work was lost before it could be copied, perhaps just after Chaucer's death.

The first version of the Prologue suggests that Chaucer wanted to dedicate the work to Queen Anne. Since it refers to Troilus, it must have been written after about 1385-6. If the second version of the Prologue is indeed a revision of the first, the fact that references to Queen Anne have been removed suggests that the revision was done after her death in June 1394. It would be wrong to assume that the Queen really instructed Chaucer to write the work, or to take too seriously the Prologue's claim that it is a 'penance' for having written stories hostile to women. This literary device imitates one first used by the French poet Machaut.

The Legend has a bad critical reputation but today it is recognized as the work in which Chaucer finally honed his narratorial skills before embarking on the General Prologue and the compilation of the Canterbury Tales, many parts of which were already complete as isolated works or translations. The dominant concern in the Legend is to challenge and recompose by inversion the conventions governing the literary representation of women and gender roles.

It used to be claimed that Chaucer stopped writing it because he was bored by the repetition of silly stories about virtuous women and wanted to get on with the Canterbury Tales, only the Queen would not let him. This is not perhaps a very helpful approach. Chaucer was clearly fascinated by the questions he was dealing with and they continue in the Canterbury Tales.

The most important themes of all these works are love, nature, and the ways the literary imagination produces books about love and nature. They are all of them (except for the Anelida) in the form of dream-visions, and all of them play subtle games with literary references, many of them veiled or obscure. In particular, the way in which the House of Fame keeps echoing Dante is intriguing, for it is not sure who in England at this time could read or had even heard of Dante, except perhaps a few friends to whom Chaucer had spoken of him.

It is certain that Chaucer was an intense reader with a great interest in thoughtful writing; in the House of Fame (lines 652-7) the eagle scolds him:

For when thy labour doon al ys,

And hast mad alle thy rekenynges,

In stede of reste and newe thynges,

Thou goost hom to thy hous anoon;

And also domb as any stoon,

Thou sittest at another book

and in the prologues to the Legend of Good Women he admits that "On bokes for to rede I me delyte/ And to hem yive I feyth and ful credence."

Troilus and Criseyde is a work on another scale altogether, 8239 lines of rhyme-royal (seven-line stanzas rhyming ababbcc) in five books, the first major work of English literature and sometimes called the first English novel on account of its concern with the characters' psychology.

The story comes from Boccaccio's Il Filostrato, and it is most intriguing that Chaucer nowhere mentions the name Boccaccio. Instead, in Troilus, he claims to be simply translating a work by a certain Lollius, wrongly assumed in the Middle Ages to have written about Troy, whereas he is in fact radically altering Boccaccio's story to make it deeper and more poetic.

When he began to write Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer was already fully aware of the need to make the English language into a poetic diction that would be as powerful in expressing emotion and reflexion as the other literary languages he knew. He was familiar with the writings of Ovid, Cicero, Virgil, Macrobius, Boethius, and Alain de Lisle in Latin, with Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio in Italian, with the Romance of the Rose and other French works, as well as with the native English romances. He had travelled, too, his mind was European. The opening lines of Troilus and Criseyde show why John Dryden called Chaucer the "father of English poetry" (in the Preface to his Fables Ancient and Modern of 1700):

To thee clepe I, thou goddess of torment,

Thou cruel Furie, sorwing ever in peyne,

Help me, that am the sorwful instrument,

That helpeth loveres, as I can, to pleyne.

For wel sit it, the sothe for to seyne,

A woful wight to han a drery feere,

And to a sorwful tale, a sory chere.

Troilus and Criseyde is set inside Troy during the Trojan War. In Book 1 of Chaucer's version, one of Priam's sons, Troilus, appears as a young warrior scornful of love, until he glimpses Criseyde in a temple. Love's arrow having wounded him, Troilus suddenly finds himself deeply in love with her. He withdraws to complain alone, but a friend of his, Pandare, overhears him and he admits he is in love with Criseyde. Pandare offers to help Troilus meet her.

Much time elapses as they slowly establish a relationship, until at last Pandare skillfully arranges for them to spend a night together. This represents the first movement, 'from woe to wele' a rise to happiness. Suddenly Criseyde learns that her father, a prophet who has fled to the Greeks, is arranging for her to leave Troy and join him. The lovers are separated by blind destiny. Once in the Greek camp, Criseyde soon turns for protection to a Greek Diomede and although she and Troilus exchange letters, soon she seems to forget him. One day Troilus finds a brooch he gave her fixed in a cloak he has torn from Diomede during the fighting, and knows that she has betrayed him. He tries to kill Diomede, but cannot. Suddenly the book seems to be over, since the love-tale is at an end:

And down from thennes faste he gan avyse

This littel spot of erthe, that with the se

Embraced is, and fully gan despise

This wrecched world, and held al vanite

To respect of the pleyn felicite

That is in hevene above; and at the laste,

There he was slayn, his lokyng down he caste.

And in hymself he lough right at the wo

Of hem that wepten for his deth so faste;

And dampned al oure werk that foloweth so

The blynde lust, the which that may not laste,M

And shoulden al oure herte on heven caste.

And forth he wente, shortly for to telle,

Ther as Mercurye sorted hym to dwelle.

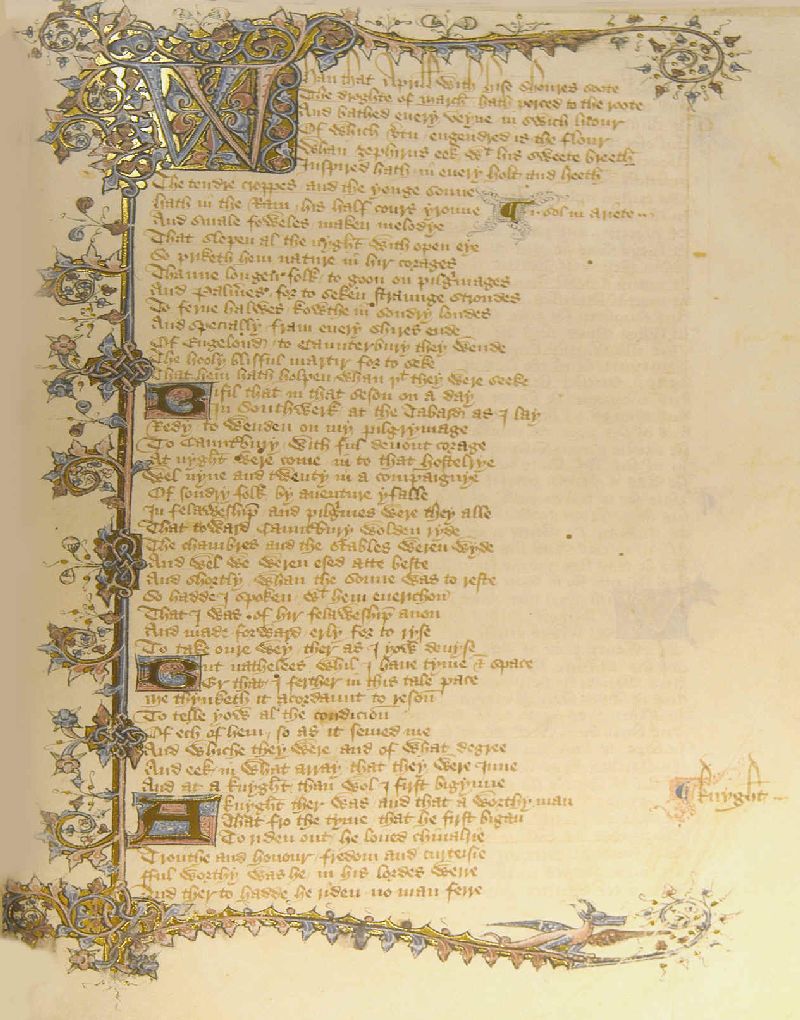

By far Chaucer's most popular work, although he might have preferred to have been remembered by Troilus and Criseyde, the Canterbury Tales was unfinished at his death. No less than fifty-six surviving manuscripts contain, or once contained, the full text. More than twenty others contain some parts or an individual tale.

The work begins with a General Prologue in which the narrator arrives at the Tabard Inn in Southwark, and meets other pilgrims there, whom he describes. In the second part of the General Prologue the inn-keeper proposes that each of the pilgrims tell stories along the road to Canterbury, two each on the way there, two more on the return journey, and that the best story earn the winner a free supper.

Since there are some thirty pilgrims, this would have given a collection of well over a hundred tales, but in fact there are only twenty-four tales, and some of these are incomplete. Between tales, and at times even during a tale, the pilgrimage framework is introduced with some kind of exchange, often acrimonious, between pilgrims. In a number of cases, there is a longer Prologue before a tale begins, the Wife of Bath's Prologue and the Pardoner's Prologue being the most remarkable examples of this.

At Chaucer's death, the various sections of the Canterbury Tales that he was preparing had not been brought together in a linked whole. His friends seem to have tried as best they could to prepare a coherent edition of what was there, adding some more linkages when they thought it necessary. The resulting manuscripts therefore offer slight differences in the order of tales, and in some of the framework links. The tales are usually found in linked groups known as 'Fragments'. The customary grouping and ordering of the tales is as follows (the commonly accepted abbreviation for each Tale is noted in parentheses):

Fragment I (A)

General Prologue (GP), Knight (KnT), Miller (MilT),

Reeve (RvT), Cook (CkT).

Fragment II (B1)

Man of Law (MLT)

Fragment III (D)

Wife of Bath (WBT), Friar (FrT), Summoner (SumT).

Fragment IV (E)

Clerk (ClT), Merchant (MerT).

Fragment V (F)

Squire (SqT), Franklin (FranT).

Fragment VI (C)

Physician (PhyT), Pardoner (PardT).

Fragment VII (B2)

Shipman (ShipT), Prioress (PrT), Chaucer: Sir Thopas

(Thop), Melibee (Mel), Monk (MkT), Nun's Priest (NPT).

Fragment VIII (G)

Second Nun SNT), Canon's Yeoman (CYT).

Fragment IX (H)

Manciple (MancT).

Fragment X (I)

Parson (ParsT).

There is great variety in different manuscripts but I and II, VI and VII, IX and X are almost always found in that order while the tales in IV and V are often spread around separately.

Modern editions are usually based on one of two manuscripts, both written by the same scribe: the Hengwrt Manuscript and the Ellesmere Manuscript. The former, in the National Library of Wales, is the oldest of all, probably copied directly from Chaucer's own disordered papers, but it lacks the Canon's Yeoman's Tale and the final pages have been lost. The latter, now preserved in California, is more complete, and beautifully produced with illustrations of the different pilgrims beside their Tales, but it shows the work of an editor who has removed some of the roughness from Chaucer's lines.

Chaucer offers in the Tales a great variety of literary forms, narratives of different kinds as well as other texts. The pilgrimage framework enriches each tale by setting it in relationship with others, but it would be a mistake to identify the narratorial voice of each tale too strongly with the individual pilgrim who is supposed to be telling it.

After the General Prologue, the Tales follow. The following is a brief outline of the different tales in the order found in the Riverside Chaucer, the standard edition.

The work begins with a General Prologue in which the narrator (Chaucer?) arrives at the Tabard Inn in Southwark to set out on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St Thomas Becket at Canterbury, and meets other pilgrims there, whom he describes. In the second part of the General Prologue the inn-keeper proposes that each of the pilgrims tell stories along the road to Canterbury, two each on the way there, two more on the return journey, and that the best story earn the winner a free supper.

The Knight's Tale: a romance, a

condensed version of Boccaccio's Teseida, set in ancient

Athens. It tells of the love of two cousins, Palamon and Arcite,

for the beautiful Emelye; the climax is a mock-battle, a

tournament, the winner of which will win her; the gods Mars and

Venus have both promised success to one of them. Arcite (servant

of Mars) wins, but he dies of wounds after his horse has been

frightened by a fury, and in the end Palamon (servant of Venus)

marries Emelye. The tale explores the themes of determinism and

freedom in ways reminiscent of the use of Boethius for the same

purpose in Troilus and Criseyde.

The Knight's Tale: a romance, a

condensed version of Boccaccio's Teseida, set in ancient

Athens. It tells of the love of two cousins, Palamon and Arcite,

for the beautiful Emelye; the climax is a mock-battle, a

tournament, the winner of which will win her; the gods Mars and

Venus have both promised success to one of them. Arcite (servant

of Mars) wins, but he dies of wounds after his horse has been

frightened by a fury, and in the end Palamon (servant of Venus)

marries Emelye. The tale explores the themes of determinism and

freedom in ways reminiscent of the use of Boethius for the same

purpose in Troilus and Criseyde.

The Miller's Prologue and Tale: a fabliau (coarse comic tale), about the cuckolding of John the Carpenter by an Oxford student, Nicholas, boarding with him and his wife Alison; Absolon, a young man from the local church, also tries to woo her, but is tricked into kissing her behind instead of her lips. Nicholas has deceived John into believing that Noah's Flood is about to come again, so John is asleep in a tub hanging high in the roof, ready to float to safety. Meanwhile Alison and Nicholas are in bed together. The climax of the tale is one of the finest comic moments in literature, when Absolon burns Nicholas's behind with a hot iron, Nicholas calls for water, John hears, thinks the flood has come, cuts the rope holding his tub, and crashes to the floor, breaking an arm. Only Alison escapes unscathed. The narrator offers no morality.

The Reeve's Prologue and Tale: a fabliau about the cuckolding of a miller told by the Reeve (who is a carpenter, and very angry with the Miller for his tale); two Cambridge students punish a dishonest miller by having sex with his wife and daughter while asleep all in one room. Again, the end involves violence, as the miller discovers what has happened but is struck on the head by his wife because his bald pate is all she can see in the dark.

The Cook's Prologue and Tale: only a short fragment exists.

The Man of Law's Introduction, Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue: a religious romance about the Roman emperor's christian daughter Constance, who goes to Syria, floats to England, and finally returns to Rome after many adventures.

The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale:

in her Prologue, the Wife of Bath tells the story of her five

marriages, while contesting the anti-feminist attitudes found in

books that she quotes; indirectly, she becomes the proof of the

truth of those books. Her Tale is a Breton Lay about a knight who

rapes a girl, is obliged as punishment to find out what women most

desire, learns from an old hag that the answer is "mastery over

their husbands" and then has to marry her. She is a "loathly lady"

but suddenly becomes beautiful when he gives her mastery over him

after receiving a long lesson on the nature of true nobility. The

tale is related to the ideas the Wife of Bath expresses in the

Prologue, it is also a kind of "wish-fulfillment" for a woman no

longer quite young. (see below, for Gower's version of the same

story)

The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale:

in her Prologue, the Wife of Bath tells the story of her five

marriages, while contesting the anti-feminist attitudes found in

books that she quotes; indirectly, she becomes the proof of the

truth of those books. Her Tale is a Breton Lay about a knight who

rapes a girl, is obliged as punishment to find out what women most

desire, learns from an old hag that the answer is "mastery over

their husbands" and then has to marry her. She is a "loathly lady"

but suddenly becomes beautiful when he gives her mastery over him

after receiving a long lesson on the nature of true nobility. The

tale is related to the ideas the Wife of Bath expresses in the

Prologue, it is also a kind of "wish-fulfillment" for a woman no

longer quite young. (see below, for Gower's version of the same

story)

The Friar's Prologue and Tale: a comic tale about a summoner (church lawyer) who goes to hell after an old woman curses him from her heart.

The Summoner's Prologue and Tale: a coarse joke told in revenge about a friar who has to find a method of sharing a fart he has been given equally among all his fellow-friars.

The

Clerk's Prologue and Tale: a pathetic tale of

popular origin, adapted by Chaucer from a French version of

Petrarch's Latin translation of a tale in Boccaccio's Decameron.

The unlikely and terrible story of the uncomplaining Griselda who

is made to suffer appalling pain and humiliation by her husband

Walter. Griselda is of very humble origin; Walter chooses her like

God choosing Israel. Suddenly he turns against her, takes away her

children, sends her back home, and years later demands that she

help welcome the new bride he has decided to marry. Without

resisting, she obeys, and at last finds her rights and children

restored to her by Walter who says he was just testing her! The

narrator cannot decide if she is a model wife for anti-feminists

or an image of humanity in the hands of an arbitrary destiny.

The

Clerk's Prologue and Tale: a pathetic tale of

popular origin, adapted by Chaucer from a French version of

Petrarch's Latin translation of a tale in Boccaccio's Decameron.

The unlikely and terrible story of the uncomplaining Griselda who

is made to suffer appalling pain and humiliation by her husband

Walter. Griselda is of very humble origin; Walter chooses her like

God choosing Israel. Suddenly he turns against her, takes away her

children, sends her back home, and years later demands that she

help welcome the new bride he has decided to marry. Without

resisting, she obeys, and at last finds her rights and children

restored to her by Walter who says he was just testing her! The

narrator cannot decide if she is a model wife for anti-feminists

or an image of humanity in the hands of an arbitrary destiny.

The Merchant's Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue: a bitter fabliau-style tale of an old husband, Januarius, with a young wife, May; at the end, the blind old man is shown embracing a pear-tree, in the branches of which May is having sex with a young man. The gods suddenly restore his sight and he sees them, but May convinces him that it is thanks to her exertions that he can see, that it is a form of prayer.

The Squire's Introduction and Tale: a fantasy romance. King Cambuscan of Tartary receives on his birthday gifts from the king of Arabia: a brass horse that can fly, for his daughter Canace a mirror that shows coming dangers and King Solomon's ring by which she can understand birds, and also a magic sword. After Canace has heard a falcon tell the sad story of her love, the mysterious story breaks off, unfinished.

The Franklin's Prologue and Tale: a Breton lay. The lady Dorigen is wooed by a squire, and she says she will accept him when all the rocks in the sea are gone. By the help of a magician he achieves this, and Dorigen's husband, told of her promise, says that she must keep her word. Touched by such sincerity, the squire releases her from her promise.

The Physician's Tale: a Roman moral tale from Livy, about Virginia, who is killed by her father to save her from the dishonouring intentions of a corrupt judge.

The Pardoner's Introduction, Prologue,

and Tale: in the Prologue, the Pardoner reveals his

own nature as a covetous deceiver; his Tale is a sermon, showing

his skill, but he concludes by inviting the pilgrims to give him

money and they get angry.

The Pardoner's Introduction, Prologue,

and Tale: in the Prologue, the Pardoner reveals his

own nature as a covetous deceiver; his Tale is a sermon, showing

his skill, but he concludes by inviting the pilgrims to give him

money and they get angry.

In the Tale, a great showpiece of moral rhetoric quite unfitted for such a rogue, he tells an exemplum against greed about three wild young men who set out to kill Death; a mysterious old man they meet tells them they will find him under a tree, but they find there gold instead. One goes to buy wine, and is killed by his two friends on his return; they drink the wine, that he has poisoned, and also die.

The Shipman's Tale: a fabliau in which a merchant's wife offers to sleep with a monk if he gives her money; he borrows the money from the merchant, sleeps with the wife, and later tells the merchant (who asks for his money on returning from a journey) that he has repaid it to his wife! She says that she has spent it all, and offers to repay her husband through time together in bed. The tale seems written to be told by a woman, perhaps it was originally given to the Wife of Bath?

The Prioress's Prologue and Tale: a religious tale, in complete contrast to the Shipman's. A little boy is killed by wicked Jews because he sings a hymn to Mary as he walks through their street. His dead body continues to sing the hymn, so the murder is found out.

The Prologue and Chaucer's Tale of Sir Thopas: a romance of the English kind, it mentions heroes such as Horn, Bevis, Guy. It is written in what seems to be a parody of English popular romance, in rattling tail-rhyme stanzas (an four-stress couplet followed by a three-stress line, twice, the third and sixth line rhyming). The hero is called Sir Thopas, he is eager to love an elf-queen but as he arrives in fairy-land he meets a giant, whom he avoids. Soon after this, Harry Bailey, the inn-keeper, stops the tale: "Namoore of this, for Goddes dignitee!" And Chaucer the pilgrim explains that he can do no better in rhyme!

Instead "Chaucer" offers to tell a "little thing" in prose, the Tale of Melibee translated from French and covering twenty pages! It is more a treatise than a tale. It contains a vague story, but mostly consists of moral debate full of moral advice in pithy sententiae about the best way of dealing with problems and how to take advice.

The Monk's Prologue and Tale: a series of seventeen "tragedies" of varying length, in the Fall of Princes tradition. The stories come from various sources, including the Bible and Boccaccio, and tell of "the deeds of Fortune" in the unhappy ends of famous people, including some near-contemporaries. At last the Knight stops the series, which claims to illustrate the power of Fortune, but becomes a list of pathetic case-histories.

The Nun's Priest's Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue: a beast-fable told in a variety of styles, mock-heroic and pedantic mainly. In place of the brevity of the ordinary fable (cf Aesop) there are constant digressions and interminable speeches. The main characters are Chauntecleer and his lady Pertelote, a cock and a hen in a farmyard; Chauntecleer dreams of a fox (he has never seen one) and this leads to a debate on the meaning of dreams. A fox then appears, flatters Chauntecleer, then grabs him but the cock suggests he insult the people chasing him and escapes when the fox opens his mouth to speak. The moral of the tale for the reader is left unclear.

The Second Nun's Prologue and Tale: a religious legend of the miracles and martyrdom of St Cecilia and her Roman husband Valerian. She instructs people to the end, even when her head has been almost completely cut off.

The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue and Tale: suddenly two new characters come riding up to join the pilgrims, a rather dubious Canon who knows alchemy, and his companion who boasts about his master's science and knavery, then tells a bitter story about a canon who tricks a priest out of a lot of money by pretending to teach him how to make precious metals. The Prologue and Tale make up a vivid portrait unlike anything else found in the Tales, shifting as they do between the Yeoman's admiration for his master and his hatred of him and his devilish arts.

The Manciple's Prologue and Tale: a tale found in Ovid about why the crow is black; it used to be white and could talk, until it told Phoebus that his wife was unfaithful. He kills her, then repents and punishes the bird. The tone of this tale is puzzling, it is neither pathetic nor comic.

The Parson's Prologue and Tale: clearly designed to be the last tale in the collection, this is no "tale" but a long moral treatise translated from two Latin works on Penitence and on the Seven Deadly Sins.

At the end of the Parson's Tale, in the Retraccion, the "maker of this book" asks Christ to forgive him: "and namely my translations and enditings of worldly vanities, the which I revoke in my retractions: as is the book of Troilus; the book also of Fame; the book of the xxv ladies; the book of the Duchess; the book of St Valentine's Day of the Parliament of Birds; the tales of Canterbury, thilke that sowen into sin...".

Yet this Retraction serves to publicize Chaucer's works and had no effect on their later publication and distribution.

The Canterbury Tales has always been among the most

popular works of the English literary heritage. When Caxton introduced printing

into England, it was the first major secular work that he printed,

in 1478, with a second corrected edition following in 1484. This

was in turn reprinted three times, before William Thynne published

Chaucer's Collected Works in 1532.

In the Reformation period, Chaucer's reputation as a precursor of the Reform movement was helped by the addition of a pro-Reformation Plowman's Tale in a 1542 edition. In 1561, even Lydgate's Siege of Thebes was added. The edition by Thomas Speght in 1598 was the first to offer a glossary; his text was revised in 1602 and this version was reprinted several times over the next hundred years, although Chaucer was not really to the taste of the Augustan readers. The first scholarly edition of the Canterbury Tales was published by Thomas Tyrwhitt in 1775.

In the last year of his life (1700) John Dryden wrote a major appreciation of Chaucer, based mainly on his knowledge of the General Prologue and certain tales which he had adapted into his own age's style:

Each Tale is presented as a separate 'work' which can be read and appreciated in its own right. There are many different classes of 'Tale' ranging from the saint's life (SNT) and the theological treatise (ParsT) through romance (KT) to the fabliau (MilT, RvT). By creating the Pilgrimage framework, Chaucer adds an extra dimension to each Tale by attributing it to a more or less distinctly characterized pilgrim. The question of the relationship between each Tale and its fictional pilgrim-teller is much debated. Usually, once a Tale has begun, it continues to the end without further reference to the pilgrimage framework. The interruption of Chaucer's Tale about Sir Thopas and of the Monk's Tale about falls of princes by weary pilgrims, and of the Pardoner's final salesman's speech by an angry Host, are powerful exceptions.

Each Tale has its own style, which is entirely determined by the kind of work it is, and is in no sense a 'dramatic' style reflecting the individuality of the proclaimed narrator. The Miller may be drunk, the narratorial voice of the Miller's Tale is not a drunken one. On the other hand, the Miller, we are told, is a 'churl' (line 3182) and he tells a churlish kind of story in terms of morality and respectability at least, no matter how brilliantly. The Knight is noble and his Tale is a romance of the kind associated with royal courts. There seems usually to be this kind of suitability of Tale to teller.

However, it must be admitted that a number of Tales were left by Chaucer without any introductory pilgrimage link-passage, one sometimes being provided by editors in the 15th century, so that the attribution of them to a particular pilgrim may not be Chaucer's. The Shipman's Tale includes lines in which the pilgrim-narrator refers to himself as a woman. This may indicate that originally this tale about sex and money had been given to the Wife of Bath and that after she was given another tale Chaucer never had time to remove those lines.

After the General Prologue, the pilgrims come into their own in brief link-passages which are in many cases full of tension as two or more of the rowdier pilgrims nearly come to blows. Always someone intervenes to restore order and the next Tale is introduced. Two pilgrims, the Wife of Bath and the Pardoner, are given a far more significant development. Each of them has a Prologue of considerable length in which they become, as it were, the subject of their own self-telling. Each of these Prologues is rooted in traditions of satire but goes far beyond them in establishing a composite portrayal of a dynamic individual in dramatic monologue.

The most important function of the pilgrimage framework, however, is the question it leaves hovering over each of the Tales as it is told: Is this Tale the best Tale? The Host's proposal of a contest invites the reader to judge all the Tales but at the same time requires the reader to reflect on the criteria by which the Tales are to be judged. What is the purpose of tale-telling, indeed of all discourse? Sentence or solas? Wisdom or pleasure? The value of a tale becomes more and more related to the value of life, and the Parson is not simply a kill-joy when he declares: 'Thou getest fable noon ytoold for me' (you get no fable told by me) and instead offers a treatise on sin and salvation. Chaucer leads the reader to the point where the ability of any fictional tale to tell the truth is challenged, though not necessarily as radically denied as the Parson would wish. The Parson himself is a fictional character, after all, a part of a Tale.

The reader is at each moment invited to read the Tales in such a

way as not to eliminate any of these dimensions.