Go back to the main Diamond Mountain page Go to the Isabella Bird page

The visit of Isabella Bird Bishop to the Diamond Mountains (Geumgang-san) in 1894

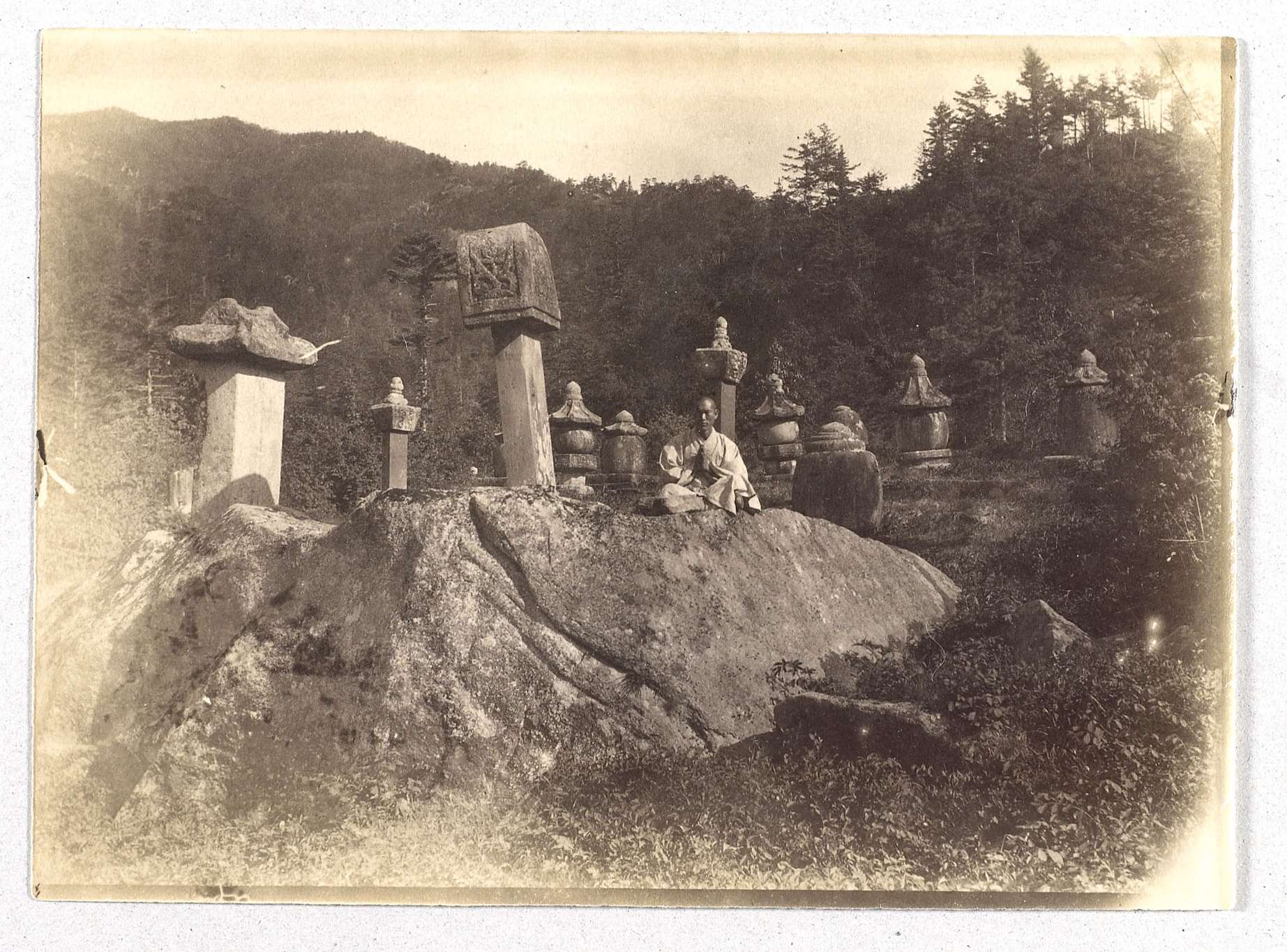

Funeral monuments at Yu-Chom-sa, a photograph by Isabella Bird in the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh

From: Korea and her Neighbors A narrative of travel, with an account of the recent vicissitudes and present position of the country

by Isabella Bird Bishop 1898

CHAPTER XI

DIAMOND MOUNTAIN MONASTERIES (1894)

(Korea and Her

Neighbors 133-149)

It was a glorious

day for the Pass of Tan-pa-Ryong

(1,320 feet above Ma-ri Kei), the western barrier of the

Keum-Kang San

region.

Mr. Campbell, of H.B.M.'s Consular Service, one of the

few Europeans who has

crossed it, in his charming narrative mentions that it

is impassable for laden

animals, and engaged porters for the ascent, but though

the track is nothing

better than a torrent bed abounding in great boulders,

angular and shelving

rocks, and slippery corrugations of entangled tree

roots, I rode over the worst

part, and my ponies made nothing of carrying the baggage

up the rock ladders. The

mountain-side is covered with luxuriant and odorous

vegetation, specially oak,

chestnut, hawthorn, varieties of maple, pale pink

azalea, and yellow clematis,

interspersed with a few distorted pines, primulas and

lilies of the valley

covering the mossy ground.

From the spirit

shrine on the summit a lovely panorama

unfolds itself, billows of hilly woodland, gleams of

water, wavy outlines of

hills, backed by a jagged mountain wall, attaining an

altitude of over 6,000

feet in the loftiest pinnacle of the Keum-Kang San. A

fair land of promise,

truly ! But this pass is a rubicon to him who seeks the

Diamond Mountain with

the intention of immuring himself for life in one of its

many monasteries. For

its name. Tan-pa, “crop-hair,” was bestowed on it early

in the history of

Korean Buddhism for a reason which remains. There those

who have chosen the cloister

emphasize their abandonment of the world by cutting off

the “Topknot” of

married dignity, or the heavy braid of bachelorhood.

The eastern

descent of the Tan-pa-Ryong is by a series

of zigzags, through woods and a profusion of varied and

magnificent ferns. A

long day followed of ascents and descents, deep fords of

turbulent streams,

valley villages with terrace cultivation of buckwheat,

and glimpses of gray

rock needles through pine and persimmon groves, and in

the late afternoon, after

struggling through a rough ford in which the water was

halfway up the sides of

the ponies, we entered a gorge and struck a smooth,

broad, well-made road, the

work of the monks, which traverses a fine forest of

pines and firs above a booming

torrent.

Towards evening

“The hills swung open to the light”; through

the parting branches there were glimpses of granite

walls and peaks reddening

into glory; red stems, glowing in the slant sunbeams,

lighted up the blue gloom

of the coniferae ; there were glints of foam from the

loud-tongued torrent

below; the dew fell heavily, laden with aromatic odors

of pines, and as the

valley narrowed again and the blue shadows fell the

picture was as fair as one

could hope to see. The monks, though road-makers, are

not bridge-builders, and

there were difficult fords to cross, through which the

ponies were left to struggle

by themselves, the mapu crossing on single logs.

In the deep water I

discovered that its temperature was almost icy. The

worst ford is at the point

where the first view of Chang-an

Sa, the Temple of Eternal Rest, the

oldest of the Keum-Kang

San monasteries, is

obtained, a great pile of temple buildings with deep

curved roofs, in a

glorious situation, crowded upon a small grassy plateau

in one of the narrowest

parts of the gorge, where the mountains fall back a

little and afford Buddhism

a peaceful shelter, secluded from the outer world by

snow for four months of

the year.

Crossing the

torrent and passing under a lofty Hong-Sal-Mun

or “red arrow gate,” significant in Korea of the

patronage of royalty, we were

at once among the Chang-an Sa buildings, which consist

of temples large and

small, a stage for religious dramas, bell and tablet

houses, stables for the

ponies of wayfarers, cells, dormitories, and a refectory

for the abbot and

monks, quarters for servants and neophytes, huge

kitchens, a large guest hall,

and a nunnery. Besides these there are quarters devoted

to the lame, halt,

blind, infirm, and solitary; to widows, orphans, and the

destitute.

These guests,

numbering 100, seemed well treated. Be-

tween monks, servants, and boys preparing for the

priesthood there may be 100

more, and 20 nuns of all ages, from girlhood up to

eighty-seven years. This

large number of persons is supported by the rent and

produce of Church lands

outside the mountains, the contributions of pilgrims and

guests, the moneys

collected by the monks, who all go on mendicant

expeditions, even up to the

gates of Seoul, which at that time it was death for any

priest to enter, and

benefactions from the late Queen, which had become

increasingly liberal.

The first

impression of the plateau was that it was a

wood- yard on a large scale. Great logs and piles of

planks were heaped under

the stately pines and under a superb Salisburia

adiantifolia, 17 feet in

girth; 40 carpenters were sawing, planing,

and hammering, and 40 or 50

laborers were hauling in logs to the music of a wild

chant, for mendicant

effort had been resorted to energetically, with the

result that the great temple

was undergoing repairs, almost amounting to a

reconstruction.

Of the forty-five

monasteries and monastic shrines

which exist in the Diamond Mountain, enhancing its

picturesqueness and

supplying it with a religious and human interest,

Chang-an Sa may be taken as a

fair specimen of the three largest, as it is undoubtedly

the oldest, assuming

the correctness of a historical record quoted by Mr.

Campbell, which gives the

date of its restoration by two monks, Yul-sa and

Chin-h'yo, as A.D. 515, in the

reign of Pop-heung, a king of Silla, then the most

important of the kingdoms,

afterwards amalgamated as Korea.

The large temple

is a fine old building of the type

adapted from Chinese Buddhist architecture, oblong, with

a heavy tiled roof 48

feet in height, with wings, deep eaves protecting masses

of richly-colored

wood-carving. The lofty reticulated roof is internally

supported on an

arrangement of heavy beams, elaborately carved and

painted in rich colors. The panels

of the doors, which serve as windows, and let in a “dim

religious light,” are

bold fretwork, decorated in colors enriched with gold.

The roofs of the

actual shrines are supported on

wooden pillars 3 feet in diameter, formed of single

trees, and the panelled

ceilings are embellished with intricate designs in

colors and gold. In one

Sakyamuni's image, with a distinctly Hindu cast of

countenance, and a look of

ineffable abstraction, sits under a highly decorative

reticulated wooden

canopy, with an altar before it, on which are brass

incense burners, books of

prayer, and lists of those deceased persons for whose

souls masses have been

duly paid for. Much rich brocade, soiled and dusty, and

many gonfalons, hang

round this shrine.

The “Hall of the

Four Sages” contains three Buddhas in

different attitudes of abstraction or meditation, a

picture, wonderfully worked

in gold and silks in Chinese embroidery, of Buddha and

his disciples, for which

the monks claim an antiquity of fourteen centuries, and

sixteen Lohans, with

their attendants. Along the side walls are a host of

daemons and animals.

Another striking shrine is that dedicated to the Lord of

the Buddhistic Hell

and his ten princes. The monks call it the “Temple of

the Ten Judges.” This is

a shrine of great resort, and is much blackened by the

smoke of incense and

candles, but the infernal torments depicted in the

pictures at the back of each

judge are only too conspicuous. They are horrible beyond

conception, and show a

diabolical genius in hellish art, akin to that which

inspired the creation of

the groups in the Inferno of the temple of Kwan-yin at

Ting-hai on Chusan,

familiar to some of my readers.

Besides the

ecclesiastical buildings and the common

guestroom, there are Government buildings marked with

the Korean national

emblem, for the use of officials who go up to Changan Sa

for pleasure.

It was difficult

for me to find accommodation, but

eventually a very pleasing young priest of high rank

gave up his cell to me.

Unfortunately, it was next the guests' kitchen, and the

flues from the fires

passing under it, I was baked in a temperature of 91°,

although, in spite of

warnings about tigers, the dangers from which are by no

means imaginary, I kept

both door and window open all night. The cell had for

its furniture a shrine of

Gautama and an image of Kwan-yin on a shelf, and a few

books, which I learned

were Buddhist classics, not volumes, as in a cell which

I occupied later, full

of pictures by no means inculcating holiness. In the

next room, equally hot,

and without a chink open for ventilation, thirty guests

moaned and tossed all

night, a single candle dimly lighting a picture of

Buddha and the dusty and

hideous ornaments on the altar below.

A 9 P.M.,

midnight, and again at 4 a.m., which is the

hour at which the monks rise, bells were rung, cymbals

and gongs were beaten,

and the praises of Buddha were chanted in an unknown

tongue. A feature at once

cheerful and cheerless is the presence at Chang-an Sa of

a number of bright,

active, orphan boys from ten to thirteen years old, who

are at present servitors,

but who will one day become priests.

It is an exercise

of forbearance to abstain from

writing much about the beauties of Chang-an Sa as seen

in two days of perfect

heavenliness. It is a calm retreat, that small, green,

semicircular plateau

which the receding hills have left, walling in the back

and sides with rocky

precipices half clothed with forest, while the

bridgeless torrent in front,

raging and thundering among huge boulders of pink

granite, secludes it from all

but the adventurous. Alike in the rose of sunrise, in

the red and gold of

sunset, or gleaming steely blue in the prosaic glare of

midday, the great rock

peak on the left bank, one of the

highest in the range, compels ceaseless admiration. The

appearance of its huge

vertical topmost ribs has been well compared to that of

the “pipes of an

organ,” this organ-pipe formation being common in the

range ; seams and ledges

halfway down give roothold to a few fantastic conifers

and azaleas, and lower

still all suggestion of form is lost among dense masses

of magnificent forest.

As I proposed to

take a somewhat different route from

Yuchom Sa (the first temple on the eastern slope) from

that traversed by my

predecessors, the Hon. G. W. Curzon and Mr. Campbell, I

left the ponies and

baggage at Chang-an Sa, the mapu, who were bent

on ku-kyong,

accompanying me for part of the distance, and took a

five days' journey in the

glorious Keum-Kang San in unrivalled weather, in air

which was elixir, crossing

the range to Yu-chom Sa by the An-mun-chai (GooseGate

Terrace), 4,215 feet in

altitude, and recrossing it by the Ki-cho, 3,570 feet.

Taking two coolies

to carry essentials, and a na-my'o

or mountain chair with two bearers, for the whole

journey, all supplied by the

monks, I walked the first stage to the monasteries of P'yo-un

Sa and

Chyang-yang

Sa, the latter at an elevation of about

2,760 feet. From it the

view, which passes for the grandest in Korea, is

obtained of the “Twelve

Thousand Peaks.” There is assuredly no single view that

I have seen in Japan or

even in Western China which equals it for beauty and

grandeur. Across the grand

gorge through which the Chang-an Sa torrent thunders,

and above primaeval

tigerhaunted forests with their infinity of green, rises

the central ridge of

the Keum-Kang San, jagged all along its summit, each

yellow granite pinnacle

being counted as a peak.

On that enchanting

May evening, when odors of

paradise, the fragrant breath of a million flowering

shrubs and trailers, of

bursting buds, and unfolding ferns, rose into the cool

dewy air, and the

silence could be felt, I was not inclined to enter a

protest against Korean

exaggeration on the ground that the number of peaks is

probably nearer 1,200

than 12,000. Their yellow granite pinnacles, weathered

into silver gray, rose

up cold, stern, and steely blue from the glorious

forests which drape their

lower heights — winter above and summer below — then

purpled into red as the

sun sank, and gleamed above the twilight, till each

glowing summit died out as

lamps which are extinguished one by one, and the whole

took on the ashy hue of

death.

The situation of P'yo-un

Sa is romantic, on the

right bank of the torrent, and is approached by a

bridge, and by passing under

several roofed gateways. The monastery had been newly

rebuilt, and is one mass

of fretwork, carving, gilding, and color, the whole

decoration being the work

of the monks.

The front of the

“Temple of the Believing Mind” is a

magnificent piece of bold wood-carving, the motif being

the peony. Every part

of the building which is not stone or tile is carved,

and decorated in blue,

red, white, green, and gold. It may be barbaric, but it

is barbaric splendor.

There too is a “Temple of Judgment,” with hideous

representations of the Buddhist

hells, one scene being the opening of the books in which

the deeds of men's

mortal lives are written.

The fifty monks of

P'yo-un Sa were very friendly, and

not impecunious. One gave up to me his oven-like cell,

but repaid himself for

the sacrifice by indulging in ceaseless staring. The

wind bells of the

establishment and the big bell have a melody in their

tones such as I have

rarely heard, and when at 4 a. m. bells of all sizes and

tones announced that

“prayer is better than sleep,” there was nothing about

the sounds to jar on the

pure freshness of morning. The monks are well dressed

and jolly, and have a

well-to-do air which clashes with any pretensions to

asceticism. The rule of

these monasteries is a strict vegetarianism which allows

neither milk nor eggs,

and in the whole region there are neither fowls nor

domestic animals. Not to

wound the prejudices of my hosts, I lived on tea, rice,

honey water, edible

pine nuts, and a most satisfying combination of pine

nuts and honey. After a

light breakfast on these delicacies, the sub-abbot, took

me to see his

grandmother, a very bright pleasing woman of eighty, who

came from Seoul

thirteen years ago and built a house within the

monastery grounds, in order to

die in its quiet blessedness. There I had to eat a

second ethereal meal, and

the hospitable hostess forced on me a pot of exquisite

honey and a bag of pine nuts.

These, the product of the Pinus pinea, which

grows profusely throughout

the range, furnish an important and nutritious article

of monkish diet, and are

exported in quantities as a luxury. They are rich and

very oily, and turn

rancid soon after being shelled. The honey is also

locally produced. The

beehives, which usually stand two together in cavities

in the rocks, are hollow

logs with clay covers mounted on blocks of wood or

stone. Leaving this friendly

hostess and the seven nuns of the nunnery behind, the

sub-abbot showed me the direction

in which to climb, for road there is none, and at

parting presented me with a

fan.

A visit to the

Keum-Kang San elevates a Korean into

the distinguished position of a traveller, and many a

young resident of Seoul

gains this fashionable reputation. It is not as

containing shrines of

pilgrimage, for most Koreans despise Buddhism and its

shaven mendicant priests,

that these mountains are famous in Korea, but for their

picturesque beauties, much

celebrated in Korean poetry. The broad backbone of the

peninsula which has

trended near to the east coast from Puk-chong southwards

has degenerated into

tameness, when suddenly Keum-Kang San, or the Diamond

Mountain, with its elongated

mass of serrated, jagged, and inaccessible peaks, and

magnificent primaeval

forest, occupying an area of about 32 miles in length by

22 in breadth, starts

off from it near the 39th parallel of latitude in the

province of Kang-won.

Buddhism, which, as in Japan, possesses itself of the

fairest spots in Nature,

fixed itself in this romantic seclusion as early as the

sixth century a. d.,

and the venerable relics of the time when for 1,000

years it was the official

as well as the popular cult of the country are chiefly

to be found in the

recesses of this mountain region, where the same faith,

though now discredited,

disestablished, and despised, still attracts a certain

number of votaries, and

a far larger number of visitors and so-called pilgrims,

who resort to the

shrines to indulge in kukyong, a Korean term

which covers

pleasure-seeking, sightseeing, the indulgence of

curiosity, and much else.

So far as I have

been able to learn, there are only

two routes by which the Keum-Kang San can be penetrated,

the one which, after

following the bed of a singularly rough torrent, crosses

the watershed at

An-mun-chai, and on or near which the principal

monasteries and shrines are

situated, and the Ki-cho, a lower and less interesting

pass. Both routes start

from Chang-an Sa. The forty-two shrines are the

headquarters of about 400 monks

and about 50 nuns, who add to their religious exercises

the weaving of cotton

and hempen cloth. The lay servitors possibly number

1,000. The four great

monasteries, two on the eastern and two on the western

slope, absorb more than

300 of the whole number. All except the high monastic

officials beg through the

country, alms-bowl in hand, the only distinctive

features of their dress being

a very peculiar hat and the rosary. They chant the

litanies of Buddha from

house to house, and there are few who deny them food and

lodging and a few cash

or a little rice.

The monasteries

are presided over by what we should

call “abbots,” superiors of the first or second class

according to the

importance of the establishment. These Chong-sop

and Son-tong are

nominally elected annually, but actually continue in

office for years, unless

their conduct gives rise to dissatisfaction. Beyond the

confirmation of the

election of the Chong-sop of those monasteries

which possess a “Red

Arrow Gate “by the Board of Rites at Seoul, the

disestablished Church appears

to be quite free from State interference. In the case of

restoring and

rebuilding shrines, large sums are collected in Seoul

and the southern

provinces, though faith in Buddhism as a creed rarely

exists.

On making

inquiries through Mr. Miller as to the way

in which the number of monks is kept up, I learned that

the majority are either

orphans or children whose parents have given them to the

monasteries at a very

early age owing to poverty. These are more or less

educated and trained by the

monks. It must be supposed that among the number there

are a few who escape

from the weariness and friction of secular life into a

region in which

seclusion and devotion are possible. Of this type was

the pale and interesting

young priest who gave up his room to me at Chang-an Sa,

and two who accompanied

us to Yu-chom Sa, one of whom chanted Na Mu Ami Tabu

nearly the whole

day as he journeyed, telling a bead on his rosary for

each ten repetitions. Mr.

Miller asked him what the words meant. “Just letters,”

he replied ; “they have

no meaning, but if you say them many times you will get

to heaven better.” Then

he gave Mr. Miller the rosary, and taught him the mystic

syllables, saying,

“Now, you keep the beads, say the words, and you will go

to heaven.” Among the

younger priests several seemed in earnest. Others make

the monasteries (as is

largely the case with the celebrated shrines of Kwan-yin

on the Chinese island

of Pu-tu) a refuge from justice or creditors, some

remain desiring peaceful

indolence, and not a few are vowed and tonsured who came

simply to view the

scenery of the Keum-Kang San and were too much enchanted

to leave it.

As to the moribund

Buddhism which has found its most

secluded retreat in these mountains, it is overlaid with

daemonolatry, and like

that of China is smothered under a host of semideified

heroes. Of the lofty

aims and aspirations after righteousness which

distinguish the great reforming

sects of Japan, such as the Monto, it knows nothing.

The monks are

grossly ignorant and superstitious. They

know nearly nothing of the history and tenets of their

own creed, or of the

purport of their liturgies, which to most of them are

just “letters,” the

ceaseless repetition of which constitutes “merit.”

Though some of them know

Chinese, and this knowledge means “education” in Korea,

worship consists in the

mumbling or loud intoning of Sanscrit or Tibetan

phrases, of the meaning of

which they have no conception. My impression of most of

the monks was that

their religious performances are absolutely without

meaning to them, and that

belief, except among a few, does not exist. The Koreans

universally attribute

to them gross profligacy, of the existence of which at

one of the large

monasteries it was impossible not to become aware, but

between their romantic

and venerable surroundings, the order and quietness of

their lives, their

benevolence to the old and destitute, who find a

peaceful asylum with them, and

in the main their courtesy and hospitality, I am

compelled to ad' mit that they

exercise a certain fascination, and that I prefer to

remember their virtues

rather than their faults. My sympathies go out to them

for their appreciation

of the beautiful, and for the way in which religious art

has assisted Nature by

the exceeding picturesqueness of the positions and

decoration of their shrines.

The route from

Chang-an Sa to Yu-chom

Sa, about 11 miles, is mainly the

rough beds of two great mountain torrents. Along this,

in romantic positions,

are three large monasteries P'yo-un Sa, Ma-ha-ly-an

Sa, and

Yu-chom Sa, besides a

number of smaller shrines, with from two to five

attendants each, one especially,

Po-tok-am sa, dedicated to Kwan-yin, picturesque

beyond description — a

fantastic temple built out from the face of a cliff, at

a height of 100 feet,

and supported below the centre by a pillar, round which

a blossoming white

clematis, and an Ampelopsis Veitchiana, in the

rose flush of its spring leafage,

had entwined their lavish growth.

No quadruped can

travel this route farther than

Chang-an Sa. Coolies, very lightly laden, and

chair-bearers carrying a na-myo,

two long poles with a slight seat in the middle, a noose

of rope for the feet,

and light uprights bound together with a wistaria rope

to support the back, can

be used, but the occupant of the chair has to walk much

of the way.

The torrent bed

contracts above Chang-an Sa, opens out

here and there, and above P'yo-un Sa narrows into a

gash, only opening out

again at the foot of the An-raun-chai. Surely the beauty

of that 11 miles is

not much exceeded anywhere on earth. Colossal cliffs,

upbearing mountains,

forests, and gray gleaming peaks, rifted to give

roothold to pines and maples, ofttimes

contracting till the blue heaven above is narrowed to a

strip, boulders of pink

granite 40 and 50 feet high, pines on their crests and

ferns and lilies in

their crevices, round which the clear waters swirl,

before sliding down over

smooth surfaces of pink granite to rest awhile in deep

pink pools where they

take a more brilliant than an emerald green with the

flashing lustre of a

diamond — rocks and ledges over which the crystal stream

dashes in drifts of

foam, shelving rock surfaces on which the decorative

Chinese characters, the

laborious work of pilgrims, afford the only foothold,

slides, steeper still,

made passable for determined climbers by holes, drilled

by the monks, and

fitted with pegs and rails, rocks with bas-reliefs, or

small shrines of Buddha

draped with flowering trailers, a cliff with a

bas-relief of Buddha, 45 feet

high on a pedestal 30 feet broad, rocks carved into

lanterns and altars, whose

harsh outlines are softened by mosses and lichens, and

above, huge timber and

fantastic peaks rising into the summer heaven's

delicious blue.

A description can

be only a catalogue. The actuality

was intoxicating, a canyon on the grandest scale, with

every element of beauty

present.

This route cannot

be traversed in European shoes. In

Korean string foot-gear, however, I never slipped once.

There was much jumping

from boulder to boulder, much winding round rocky

projections, clinging to

their irregularities with scarcely foothold, and one's

back to the torrent far

below, and much leaping over deep crevices and “walking

tight-rope fashion” over

rails. Wherever the traveller has to leave the

difficulties of the torrent bed

he encounters those of slippery sloping rocks, which he

has to traverse by

hanging on to tree trunks.

Our two priestly

companions were most polite to me,

giving me a hand at the dangerous places, and beguiling

the way by legends,

chiefly Buddhistic, concerning every fantastic and

abnormal rock and pool, such

as the Myo-kil Sang, the colossal figure of Buddha

referred to before, a

pothole in the granite bed of the stream, the wash-basin

of some mythical

Bodhisattva, the Fire Dragon Pool, and the

bathing-places of dragons in the

fantastic Man-pok-Tong (Grotto of Myriad Cascades), and

the Lion Stone which

repelled the advance of the Japanese invaders in 1592.

Beyond the third

monastery the gorge becomes wider and

less fantastic, the forest thinner, allowing scattered

glimpses of the sky, and

finally some long zigzags take the traveller up to the

open grassy summit of

the An-mun-chai, on which plums, pears, cherries, blush

azaleas, and pink

rhododendrons, which had long ceased blooming below,

were in their first flush

of beauty. To the west the difficult country of the

previous week's journey,

gray granite, deep valleys, and tiger-haunted forest

faded into a veil of blue,

and in the east, over diminishing forest-covered ranges,

gleamed the blue Sea

of Japan, more than 4,000 feet below.

On the eastern

descent there are gigantic pines and

firs, some of them ruthlessly barked, and the long

dependent streamers of the

gray-green Lycopodium Sieboldii with which they

are festooned, give the

forest a funereal aspect. Of this the peculiar fringed

hats are made which are

worn on occasion by both monks and nuns. After many

downward zigzags, the track

enters another rocky gorge with a fine torrent, in the

bed of which are huge

“potholes,” shown as the bathingplaces of dragons, whose

habits must have been

much cleanlier than those of the present inhabitants of

the land.

The great

monastery of Yu-chom Sa,

with its

many curved roofs and general look of newness and

wealth, is approached by

crossing a very tolerable bridge. The road, which passes

through a well-kept

burial-ground, where the ashes of the pious and learned

abbots of several

centuries repose under more or less stately monuments,

was much encumbered near

the monastery by great pine logs newly hewn for its

restoration, which was

being carried out on a very expensive scale.

The monks made a

difficulty about receiving us, and it

was not till after some delay, and the production of my

kwan-ja, that we

were allotted rooms in the Government buildings for the

two days of our halt.

After this small difficulty, they were unusually kind

and friendly, and one of

the young priests, who came over the An-mun-chai with

us, offered Mr. Miller

the use of his cell on Sunday, saying that “it would be

a quieter place than

the great room to study his belief” !

I had hoped for

rest and quiet on the following day,

having had rather a hard week, but these were

unattainable. Besides 70 monks

and 20 nuns, there were nearly 200 lay servitors and

carpenters, and all were

bent upon ku-kyong, the first European woman to

visit the Keum-Kang San

being regarded as a great sight, and from early morning

till late at night

there was no rest. The kang floor of my room

being heated from the

kitchen, it was too hot to exist with the paper front

closed, and the crowds of

monks, nuns, and servitors, finishing with the

carpenters, who crowded in

whenever it was opened, and hung there hour after hour,

nearly suffocated me,

the day being very warm. The abbot and several senior

monks discussed with Mr.

Miller the merits of rival creeds, saying that the only

difference between

Buddhists and ourselves is that they don't kill even the

smallest insect, while

we disregard what we call “animal life,” and that we

don't look upon monasticism

and other forms of asceticism as means of salvation.

They admitted that among

their priests there are more who live in known sin than

strivers after

righteousness.

There are many

bright busy boys about Yu-chom Sa, most

of whom had already had their heads shaved. To one who

had not, Che on-i gave a

piece of chicken, but he refused it because he was a

Buddhist, on which an

objectionable-looking old sneak of a priest told him

that it was all right to

eat it so long as no one saw him, but the boy persisted

in his refusal.

At midnight, being

awakened by the boom of the great

bell and the disorderly and jarring clang of innumerable

small ones, I went, at

the request of the friendly young priest, our

fellow-traveller, to see him

perform the devotions, which are taken in turn by the

monks.

The great bronze

bell, an elaborate piece of casting

of the fourteenth century, stands in a rude, wooden,

clay-floored tower by

itself. A dim paper lantern on a dusty rafter barely

lighted up the white-robed

figure of the devotee, as he circled the bell, chanting

in a most musical voice

a Sanscrit litany, of whose meaning he was ignorant,

striking the bosses of the

bell with a knot of wood as he did so. Half an hour

passed thus. Then taking a

heavy mallet, and passing to another chant, he circled

the bell with a greater

and ever-increasing passion of devotion, beating its

bosses heavily and

rhythmically, faster and faster, louder and louder,

ending by producing a burst

of frenzied sound, which left him for a moment

exhausted. Then, seizing the

swinging beam, the three full tones which end the

worship, and which are

produced by striking the bell on the rim, which is 8

inches thick, and on the

middle, which is very thin, made the tower and the

ground vibrate, and boomed

up and down the valley with their unforgettable music.

Of that young monk's

sincerity, I have not one doubt.

He led us to the

great temple, a vast “chamber of

imagery,” where a solitary monk chanted before an altar

in the light from a

solitary lamp in an alabaster bowl, accompanying his

chant by striking a small

bell with a deer horn. The dim light left cavernous

depths of shadow in the

temple, from which eyes and teeth, weapons, and arms and

legs of otherwise

invisible gods and devils showed uncannily. Behind the

altar is a rude and

monstrous piece of wood-carving representing the

upturned roots of a tree,

among which fifty-three idols are sitting and standing.

As well by daylight as

in the dimness of midnight, there are an uncouthness and

power about this

gigantic representation which are very impressive. Below

the carving are three

frightful dragons, on whose faces the artist has

contrived to impress an

expression of torture and defeat.

The legend of the

altar-piece runs thus. When

fifty-three priests come to Korea from India to

introduce Buddhism, they reached

this place, and being weary, sat down by a well under a

spreading tree.

Presently three dragons came up from the well and began

a combat with the

Buddhists, in the course of which they called up a great

wind which tore up the

tree. Not to be out-manoeuvred, each priest placed an

image of Buddha on a root

of the tree, turning it into an altar. Finally, the

priests overcome the

dragons, forced them into the well, and piled great

rocks on the top of it to

keep them there, founded the monastery, and built this

temple over the dragons'

grave. On either side of this unique altar-piece is a

bouquet of peonies 4 feet

wide by 10 feet high.

The “private

apartments “ of this and the other

monasteries consist of a living room, and very small

single cells, each with the

shrine of its occupant, and all very clean. It must be

remembered, however,

that this easy, peaceful, luxurious life only lasts for

a part of the year, and

that all but a few of the monks must make an annual

tramp, wallet and

begging-bowl in hand, over rough, miry, or dusty Korean

roads, put up with vile

and dirty accommodation, beg for their living from those

who scorn their

tonsure and their creed, and receive “low talk “ from

the lowest in the land.

Just before we

left, the old abbot invited us into his

very charming suite of rooms, and with graceful

hospitality prepared a repast

for us with his own hands — square cakes of rich oily

pine nuts glued together

with honey, thin cakes of “popped” rice and honey, sweet

cake, Chinese sweetmeat,

honey, and bowls of honey water with pine nuts floating

on its surface. The oil

of these nuts certainly supplied the place of animal

food during my enforced

abstinence from it, but rich vegetable oil and honey

soon pall on the palate,

and the abbot was concerned that we did not do justice

to our entertainment. The

general culture produced by Buddhism at these

monasteries, and the hospitality,

consideration, and gentleness of deportment, contrast

very favorably with the

arrogance, superciliousness, insolence, and conceit

which I have seen elsewhere

in Korea among the so-called followers of Confucius.

When we departed

all the monks and laborers bade us a courteous

farewell, some of the older priests accompanying us for

a short distance.

After descending

the slope by the well-made road which

leads down to the large monastery of Sin-kyei

Sa, at the northeast foot

of the Keum-Kang San, we left it for a rough and

difficult westerly track,

which, after affording some bright gleams of the Sea of

Japan, enters dense

forest full of great boulders and magnificent specimens

of the Filix mas

and Osmumda regalis. A severe climb up and down

an irregular, broken

staircase of rock took us over the Ki-cho Pass, 3,700

feet in altitude, after

which there is a tedious march of some hours along bare

and unpicturesque

mountain-sides before reaching the well-made path which

leads through pine

woods to the beautiful plateau of Chang-an Sa.

The young priest had kept

our baggage carefully, but the heat of his floor had

melted the candles in the

boxes and had turned candy into molasses, making havoc

among photographic

materials at the same time !