Father Charles Hunt: Missionary and Martyr

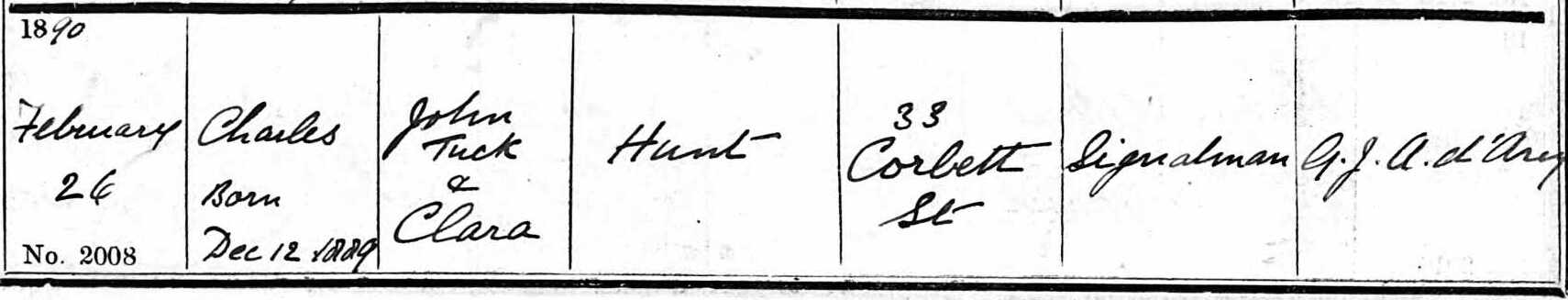

John Tuck

Hunt was born in Wootton Bassett, Wiltshire in 1858,

the son of William Hunt and Maria (Tuck) who had

married in 1847. John Tuck Hunt had married Clara

Elizabeth Hobbs (1859-1914) at Bedminster in 1885 and

they had 3 children, John, William and Charles before

John Tuck Hunt died in 1890, aged only 32. At the 1891

Census Clara Elizabeth, a widow, was living at 16

Ashley Street, Bristol, with the 3 children and her

mother Elizabeth Shepstone (aged 75, she had married

Clara's (divorced?) father John Hobbs (1814-1884) at

Bedminster in 1867, some years after Clara's birth).

At the 1901 Census Clara and Charles were living there

alone while John and William were

boarding at the school known as Queen Elizabeth's

Hospital. Educated at Newfoundland Road Board School,

Bristol, Charles was employed for a time as a

solicitor's clerk; and apprenticed to an upholsterer

in Bristol; he then spent a year in the Society of the

Evangelist brotherhood, Wolverhampton; and a year at

Canning Town's St Cedd Church before studying for the

Anglican priesthood at St Augustine's College

1911-1915, the

(former) missionary college of the Anglican Communion

in Canterbury. He left for Korea as an S.P.G.

missionary before ordination, having earned a Licence

in Theology from the University of Durham by his

studies at Canterbury. He maintained a contact with

St. Augustines, writing them a total of 38 letters

throughout his life. At the 1911 Census, his 2

brothers were still living in Ashley Street with their

mother, John (24) is a "theological student" while

William is a commercial traveller. Their later lives

are not recorded.

Arriving in

Korea in 1915 together with Ernest Henry Arnold

(1890-1950 for a biography see at the foot

of this page), he went to live in Ganghwa Island

to learn Korean. In 1916 Hunt was ordained deacon

together with Arnold and served in the church in

Jincheon, North Chungcheong Province until their

ordination as priests in 1917, after which he served

at the Cathedral in Seoul, living at least for a time

with Bishop Trollope (1862-1930) and Fr.

Henry John Drake SSM, (who served in Korea

1898-1941) in the Bishop’s Lodge beside the Anglican

Cathedral in Seoul. None of them was married and

together they constituted a kind of miniature

monastery.

In 1920, Bishop

Trollope and Father Hunt travelled together to

England, the Bishop to attend the Lambeth Conference,

while Father Hunt gave a number of talks in various

parishes. They arrived in England, having crossed

North America by train, on June 15, and Fr. Hunt wrote

(in a letter to children in an issue of Morning

Calm): “at St. Bartholomew's, Herne Bay, a

little girl ran up to me and said: “Please, Father,

here is sixpence for you; I was going to buy a

photograph in a shop, but I want to give it to you for

Corea.” I was much touched by her self-sacrifice.

About a month ago I was at Rosliston, in Derbyshire,

and the kindergarten children gave me six beautiful

Nelson Bible Pictures for our children in Corea. How

kind of them!”

During his

time in Korea, Fr. Hunt produced a number of plays,

including “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” at Seoul Foreign

School (the only photo of a young Fr Hunt on the

Internet is in

https://www.seoulforeign.org/about/history 1930s history) as well as a regular

series of performances of plays by Shakespeare. “As You Like It” was

performed in 1931, with a performance for the foreign

community and a separate one for Koreans and Japanese

learning English. Hunt also produced at least one

nativity play, with Koreans, in the Cathedral Crypt

Library at Christmas 1934. The Bishop's letter in Morning

Calm for April 1935 noted that "Fr Hunt had

procured a record of Stille Nacht, which was

to be played as soft music on a gramophone.

Unfortunately the records seem to have got mixed, and

the Wise Men approached with slow dignity to the

strains of the Hawaiian Fox Trot!" He is also

reported by a Korean source to have been familiar with

the celebrated Korean writer Lee Gwang-soo.

In 1928 Fr. Hunt was put in charge of the Anglican mission to Gyeonggi Province and had a house in Yeoju, probably linked to St Anne's (or Anna's) Hospital which had been established by Dr Anne Borrow in 1922, providing medical benefits to poor farmers. She ran it until 1940, when it was forced to close. This would explain his interest in the royal tombs in that area, about which he wrote in the RAS Transactions. He also taught at St. Michael’s Theological Seminary in Incheon (a 1926 issue of Morning Calm indicated that “Fr. Hunt contributes two lectures a week on Church History and two more on Parochialia (including Church music)” The Japanese finally closed the Seminary on March 13, 1940. He regularly wrote a Letter for Children for the magazine Morning Calm and helped care for the boys in the little hostel the Anglicans had established for street boys and orphans near the Cathedral. In 1930 Bishop Trollope died of a heart attack as the ship on which he was returning from Europe after the Lambeth Conference struck another ship while entering Kobe harbor. He was succeeded by Bishop Alfred Cecil Cooper (see below for his biography). Father Hunt left Korea just before the start of the war, together with some of the other English clergy, and served during the war as a naval chaplain. Fr. Hunt says in his 1949 London talk (below) that he found himself serving on a ship that visited Japan soon after the end of the war and took advantage of that to visit Korea, although that seems rather unlikely.

Bishop Cooper was able to return to Korea in

April 1946 and his diary says that Fr. Hunt

joined him there on 4 October 1946. It was not until

January 1947 that Sister Mary Clare was able

to return to Korea. From 1946 onwards, Fr. Hunt

was Vicar General and seems to have been busy. Writing

in Morning

Calm, June 1948, when Bishop Cooper was on his

way to the Lambeth Conference, he noted that he was

teaching English on a casual basis to many students

and more formally to members of the research

department of the Bank of Chosen. He lectured to US

Red Cross societies, and was heavily involved in the

RAS. He periodically stood in for American chaplains

and took services wherever he travelled. Bishop

Cooper was able to travel to England to attend

the 1948 Lambeth Conference thanks to donations from

the (mainly American military) congregation at the

Cathedral in Seoul (The Living Church, Volume 116, May 16,

1948 page 9). He travelled as he had in 1920, sailing

eastward to North America, then travelling across the

United States before taking a ship at New York for

England. In 1948 he had a considerable number of

speaking engagements in the United States, no doubt

part of a post-war fund-raising campaign. He gave a

talk at Chatham House (the Royal Institute of

International Affairs) in London on June 30th 1948.

Father Hunt arrived in

England on 25 January 1949, having flown from Hong

Kong in four days. This must have been at least in

part a fund-raising tour, following up on the visit by

the Bishop the previous year. He gave a talk at

Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International

Affairs) in London on 17 August 1949, prior to

returning to Korea in September. He also spoke at the 248th

annual meeting of the SPG in London, stressing the

need for more missionaries in Korea. He is listed as

RAS Korea’s Vice-President for 1948-9 in Volume 31 of

Transactions,

which was printed in Hong Kong (dated 1948-9) and

became the President of the Royal Asiatic Society

(Korea) at the start of 1950 (listed as such in Volume

32 of Transactions

(Dated 1951 and also printed in Hong Kong after the

North Korean withdrawal, allowing the inclusion of a

note by the Librarian about the fate of the RAS

Library during the North Korean occupation, but of

course without any information about the fate of Fr.

Hunt).

After

refusing to leave Seoul at the outbreak of hostilities

on June 25, 1950, Father Hunt was captured and

taken North together with the Anglican Bishop Cooper,

Sister Mary Clare (Witty) and other religious figures,

including the Apostolic Delegate Bishop Patrick Byrne

(a Maryknoll missionary, who also died in captivity),

Monsignor Thomas Quinlan (St. Columban’s Society,

Prefect-Apostolic of Chunchon, who survived), a number

of Catholic priests and sisters, American military,

and several diplomats including Vyvyan Holt, the

British Minister to South Korea and George Blake,

vice-consul, later to become notorious as a Soviet

spy. Father Albert William Lee (1893-1950), who came

to Korea in 1920 and was Principal of the Theological

College in 1950, was arrested at Incheon by North

Korean forces, together with two Korean clergy, in

July 1950, and all disappeared without trace.

Charles

Hunt died at the end of the terrible Death

March. Information about his last weeks is given by

Larry Zellers (In

Enemy Hands: A Prisoner in North Korea): “(page

100) Monsignor Quinlan and someone else were assisting

Father Charles Hunt, the Anglican priest. A very large

man with foot problems, he found it difficult to keep

up with the fast pace of the march. Monsignor and his

partner were supporting Father Hunt’s upper body,

while the lower lagged behind by about three feet.

This unnatural position placed an added burden on the

two carriers. Father Hunt wore excellent shoes, but

either they didn’t fit him very well or else they

couldn’t fit because of gout. I remembered his

problems with gout as far back as the schoolhouse in

Pyongyang. When I asked him about it on one occasion,

he sarcastically replied: “I always blame such things

on that tomato juice I drank last night.” (Father Hunt

was very fond of whisky). The only time so far in our

prison experience that we had had anything close to a

balanced diet was at Manpo. Father Hunt, however, had

not been able to eat the dried fish supplied to us

there. To have missed the relatively good diet during

that one month at Manpo was to place oneself at added

risk when the diet degenerated. He was thus able to

survive as far as Chunggangjin, in the far North, very

close to the Yalu River, then they finally arrived in

Hanjang-ni, a few hours' march to the east, where he

died, three weeks after Sister Mary Clare, the Irish

Anglican sister from Seoul. Larry Zellers: Page 118:

“We arrived in Chunggangjin on November 8, having

departed Manpo on October 31.... In Chungganjin we

were quartered for a week in an old school house,

where we were met by the women and the elderly who had

been transported by bus and truck from Chasong. Helen

Rosser came up to inform me that Sister Mary Clare had

died after she arrived at Chunggangjin.” See

more about Sister

Mary Clare

Bishop

Cooper in his diary gives the death dates for

Sister Mary Clare as 6 November 1950 and for Father

Hunt as 20 November 1950. An article in The Living Church

of May 10, 1953, just after Bishop Cooper was

released, includes this: “Father Hunt, already a sick

man at the time of his capture, died in Bishop Cecil’s

arms. Sister Mary Clare, who had remained in Korea to

be with the Korean Sisters of the Holy Cross, died

also, but apart from the Bishop, since women were not

allowed to be with men. She was cared for by the Roman

Catholic Sisters, who risked their lives to bury her

and to bring her cross and ring to Bishop Cecil as a

testimony of her death. Bishop Cecil knows, as we all

realize, that death came to these two as a merciful

release. Both had been in ill health, neither could

have faced long captivity. They had walked until their

shoes were worn through, and later Fr. Hunt had walked

to the bones of his feet. He had never been even a

mild walker, and could not live on Korean food.”

The fate of

the prisoners was discussed during the Panmunjom

Armistice negotiations and in the

list of names Father Hunt is almost the only

person without a note indicating “next of kin.”

Fr. Hunt

published several articles in the Transactions of

RAS Korea

Some

Pictures and Painters of Corea. XIX:1-34. 1930.

Diary

of a Trip to Sul-Ak San [Sŏrak-san] (Via the Diamond

Mountains) in 1923. XXIV:1-14. 1935.

The

Historic Town of Yo-ju [Yŏju], Its Surroundings and

Celebrities. XXXI:24-34. 1948-49.

Supplement

to Article on Yo-Ju [Yŏju] in Vol. XXXI.

XXXII:79-82. 1951.

Two annual reports on his work in Korea, written by

Fr. Hunt for the SPG, are available and have been

transcribed, those for 1931 and 1940.

Many issues of Morning Calm are

available online (Index).

A few contain texts by Fr. Hunt.

Some of the information in

the above text (and the photos) have come from or been

corrected by James Hoare, a scholar and the first

British Representative in Pyongyang, to whom I am most

grateful.

| Father Ernest Henry Arnold was born in Devizes, Wiltshire 1890, son of an ironmoulder, Herbert Arnold and Ann Rebecca (Whitehouse) who had married in 1880 in Bath of 2, Estcourt Crescent, Devizes. At the 1901 Census their oldest son Robert (born in Bath 1881) was an engineer’s turner, Herbert (born 1882 in Devizes) was a railway clerk, Nellie (born in Devizes 1884) was a nurse domestic and Ernest, the last, just 10, was studying at Southbroom Elementary School; he was a pupil teacher 1907-1909; then spent 2 years in the Community of the Resurrection at Mirfield; he then prepared to be a missionary by studying at St Augustines College: 1909-1911 and at Selwyn College, Cambridge 1913-1915 then left for Korea with Charles Hunt. He died July 30, 1950. Some photographs of him are listed in the catalogue of the Birmingham archive of Korean Mission papers. He served as the head of the St. Michael’s Seminary from November 1928 until the start of 1933. During his years in Korea, Fr. Arnold was the Vicar Rural for the Japanese congregation, a post he held until 1941. In a post-war letter, he noted that he and Fr Drake were instructed to stay on in Korea as long as they could. In 1942, they were repatriated by the Japanese, ending up in South Africa. In Arnold's case, he noted later that he had been instructed by Bishop Cooper to stay on in South Africa until he left in 1946 to return to Korea. (Fr. Drake remained in South Africa until his death aged 80 in 1947 at Modderport, South Africa - Morning Calm December 1947.) However, as there was no longer a Japanese congregation in Korea, Bishop Cooper told Arnold to go to Japan instead. Somewhat under protest, but obedient to the decision of the bishop, he did so, though he hoped to come back to Korea one day. Instead, he became the liaison officer for the SPG in Japan, (letter to Morning Calm, June 1947), where he arrived at Kure on 26 August 1947. He then re-established links with Japanese from Korea and ran the Anglican Tokyo theological college. He acted as liaison officer for the Archbishop of Canterbury. It seems likely that he died in Japan, not as a result of the Korean War. |

Fr. Hunt's signature in a bound copy of RAS Korea's Transactions owned by Brother Anthony. |

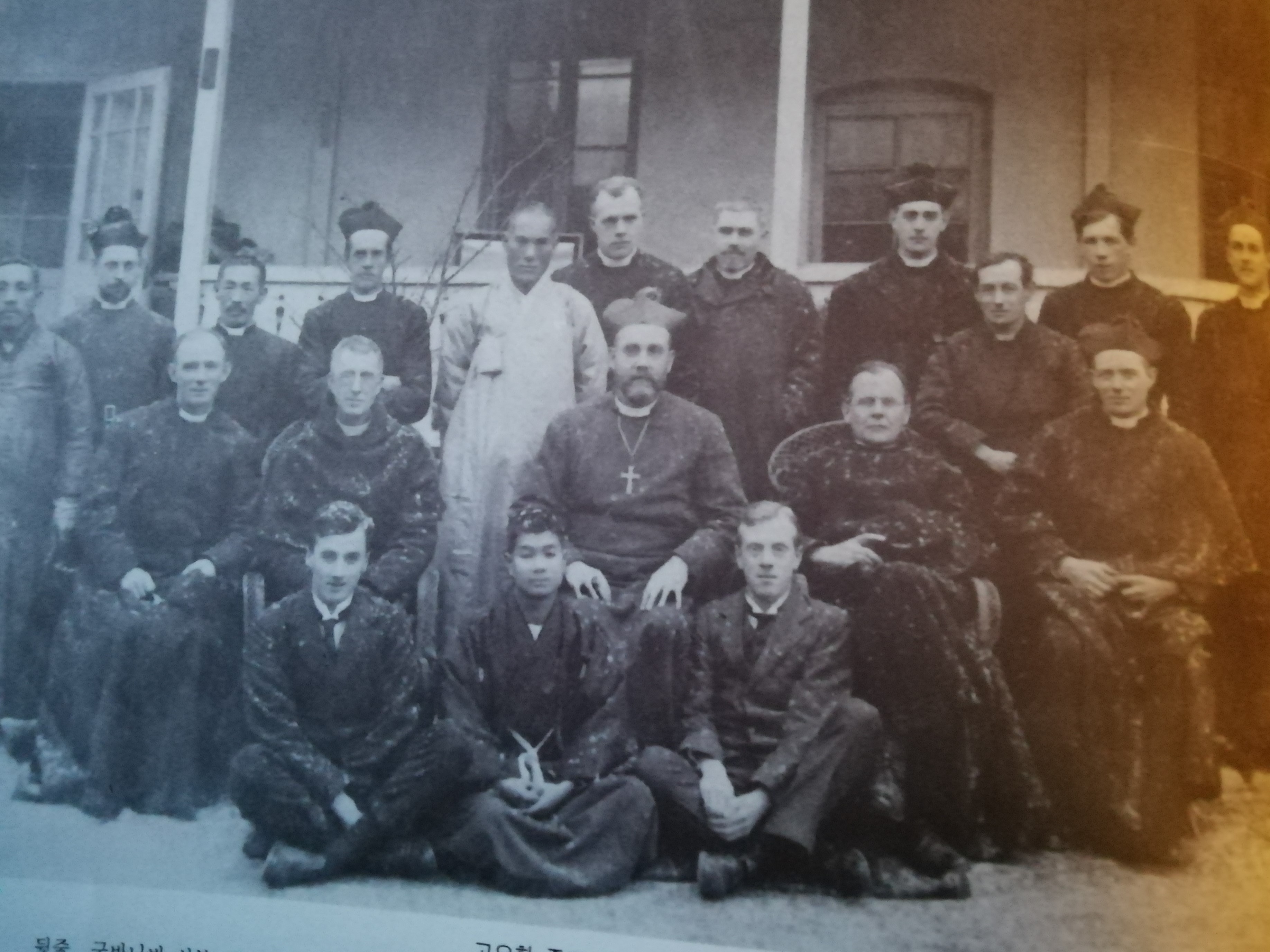

In this undated picture of Bishop Trollope with his clergy, Ernest Arnold and Charles Hunt are sitting on the ground with a Japanese seminarian (?) between them. They are not wearing clerical dress so the picture must date from 1915-16, probably before they were ordained as deacons.  The ordination of Fathers Hunt and Arnold was celebrated in 1917. This picture is said to be of a 1917 September ordination (presumably of the 2 Korean priests in the front row) while Fathers Hunt and Arnold, already priests, are standing in the back row.

These photos are copied from the centenary album 대한송공회 백 년 |