Dilkusha In India and in

Seoul

The house Dilkusha Kothi (heartís delight) near Lucknow in

north-eastern India (left) was constructed around 1800 -

1805, designed by the British Major Gore Ouseley, an entrepreneur,

linguist and diplomat, for the Nawab of Oudh, Nawab Saadat Ali Khan. The design is usually said to bear a startling

resemblance to the style of Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland,

England (right). The park and house were a center of fighting during the

Indian Uprising of 1857-8 but the house may have finally fallen

into ruins rather later, at least by the late 1890s. The park

remains until now.

Dilkusha

in Seoul

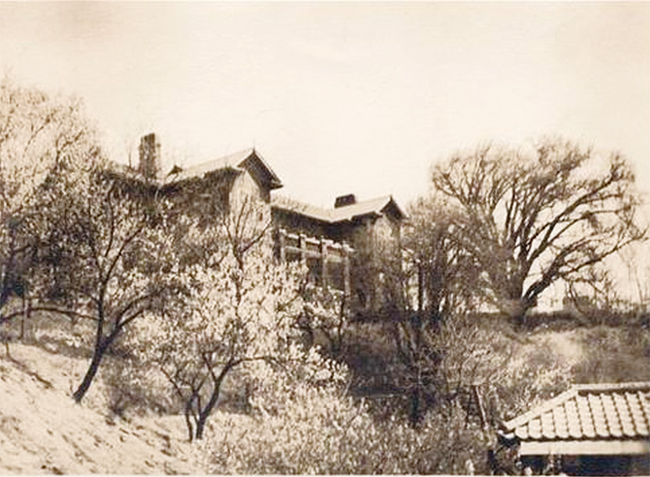

First built by Bruce and Mary Taylor in 1923, the house was

located on an open hillside overlooking Seoul, beside a huge, very

ancient gingko tree. It received its name because Mary Linley had

visited the ruins in Lucknow while she was touring India as an

actress, and had resolved to give the name to her own house one

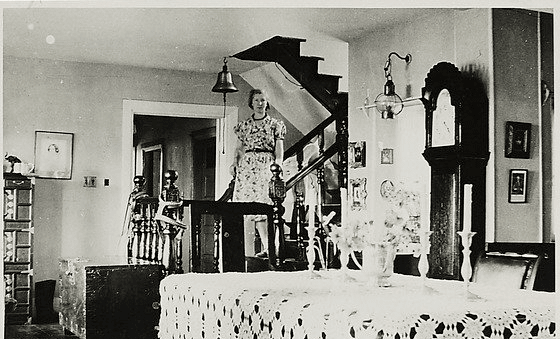

day. Read Mary's long

description: building the house, its interior (below

left), and its rebuilding after destruction by fire.

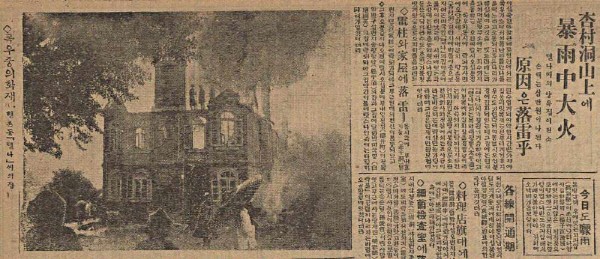

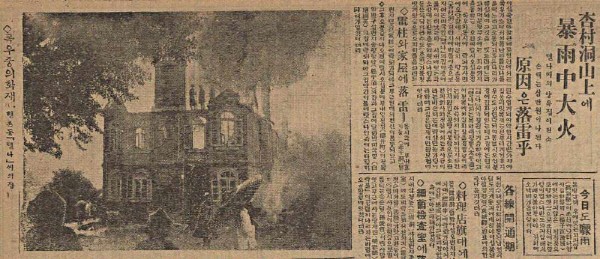

Struck by lightning on July 26 1926, while the owners were in

California, the house was seriously damaged, the entire contents

of the attic, a fine collection of antiques, was lost, as was the

upstairs floor.

|

After the 1926 fire, Bruce Taylor's brother Bill supervised the

rebuilding as best he could, and the family resumed life there in

the autumn of 1929. From 1927-29 the

Boydell family from Australia lived in the house. The

Grigsbys lived in rooms upstairs 1929-1930. Read Faith Norris's

recollections of the house (she was only nine years

old and her mother told her nothing about the fire, her 'memories'

are mostly quite wrong). The fine garden with the old tree was

especially memorable. There was a spring which the Koreans living

in the neighborhood to the west of the house had always used and

to which the Taylors had to grant access.

The house from the East ( above and below left, with the gingko)

and from the West (below right)

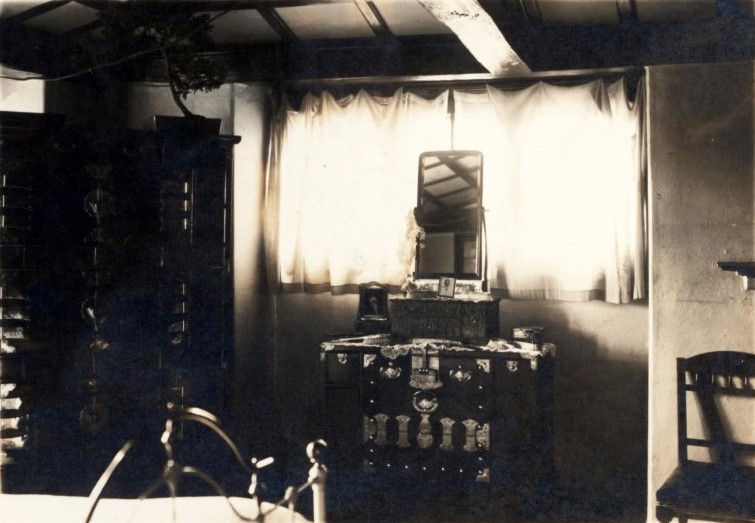

Mary Taylor was detained in the house for some weeks in late 1941

after the attack on Pearl Harbor, then obliged to leave Korea. In

the following year the house was stripped of its furnishings,

which were sold by the Japanese authorities and the proceeds put

into a bank account "for after the war.". When Mary returned to

Seoul to bury her husband's ashes in 1948, the stripped house had

been somewhat repaired; it survived the Korean War, but in the

following decades Seoul changed very much and the garden (though

not the gingko) disappeared. The house was inhabited by several

different families although it seems that none had any legal title

to it. It became increasingly run-down. The house has now been

taken over by Seoul City and after it has been restored, late in

2020 it will become a museum dedicated to the Taylors in the care

of the Seoul Museum of History. The main reason for this interest is the

unique role at the time of the 1919 March 1 Independence Movement

claimed for A. W. Taylor by his wife in her memoir Chain of Amber.

A. W. Taylor and the March 1 Korean Independence Movement: some

questions

Mary and Bruce's son, Bruce Tickell Taylor, visited

Seoul

and Dilusha in 2007 at age 88. Bruce was born in Severance

Hospital, Seoul, the day before the Independence Uprising of March

1, 1919. His mother, Mary Linley Taylor, in her book Chain of

Amber page 156 (as well as Bruce Tickell Taylor early in his

memoir Dilkusha by the Ginkgo Tree) claims that her

husband, visiting her in the hospital that evening, picked up the

baby and discovered copies of the Declaration of Korean

Independence hidden beneath it, some having been printed in the

hospital cellar in preparation for the next day's uprising. She

writes that he gave a copy to his brother Bill and sent him off to

Japan, hiding the text in the heel of his shoe, to transmit the

text to the American press (fearing censorship inside of Korea).

This, they both claim, was the initial source of western knowledge

about the March 1 uprising.

However, the story found in Mary's book and repeated by her family

is not very accurate. Certainly, Taylor was acting a correspondent

for Associated Press, mainly because of international interest in

the funeral of Emperor Gojong. He was also aware of growing

demands for independence among the Koreans and he was possibly

(but not certainly) the author of the first articles

about the March 1st Declaration published in North America on

March 13. However, the text quoted in those articles is not that

of the 'official ' declaration drafted by Choi Nam-seon, signed in

a Seoul restaurant, and read in Pagoda Park on March 1, but a

different text, composed and disseminated by a group called The

Korean National Independence Union. It seems unclear why there are

2 or even 3

different Declarations issued simultaneously, (an earlier

3rd text was released in Tokyo on February 8) and also various

suggestions of how they were disseminated, but the story of either

text being hidden beneath a new-born baby seems unlikely. The

Independence Union's Manifesto was first smuggled to Shanghai

where it was telegraphed on March 9 to Ahn Chang-ho, president of

the Korean Association of North America, in San Francisco. It is

quite possible that from there it was sent out to the North

American press. The translated

text of the 'official' March 1 Declaration of Independence

was carried to the United State by the newspaper owner V. S. McClatchy hidden in his money

belt (he

had been on the streets of Seoul on March 1) and published there

later in March. There is no indication of who might have

translated it.

On page 157-8 of Chain of Amber, Mary goes on to claim

that on March 1 (she is not clear about the chronology), the 'next

morning' after discovering the hidden Declaration(?), her husband

told her that 'yesterday' he had gone 'to Suwon and Chunju,' first

alone and then with the British and American Consuls and had taken

photographs of the Japanese setting fire 'to whole villages,' and

that they had locked Christians in a church then shot them through

the windows, and "this practice spread the length of the

peninsula." She claims that "during the (following?) morning" he

went alone to visit Governor General Hasegawa, showed him the

photos and demanded an end to the massacres, which was done.

Unlike his mother, Bruce T. Taylor knows the name of the place

where the most notorious massacre occurred, Ji Amri, with Christians locked

inside a church which was then set alight. He also knows that his

father had gone with an American consular official and H. H.

Underwood. Neither of he nor his mother seem to realize that the

atrocities happened much later, more than a month after March 1, on April 15.

It is a well-known fact that the foreigner who took a photograph

just after the Jeamni incident was Francis

Scofield, and the most extensive account of all these events

is that published in 1920, in Canadian journalist F. A. Mckenzie's

Korea's Fight For Freedom

Chapter 14 and Chapter

15. There are ample

records of the visits made by missionaries and consuls with

A. W. Taylor to the site of these atrocities, and of the

representations made to the Governor by missionaries and consuls,

it is incorrect to claim that Taylor acted alone. The best source

is The

Korean Situation : authentic accounts of recent events

by the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America.

Commission on Relations with the Orient. 1919.