The 18th century

Augustan Satire

In Restoration London, the court was not very important. Wealthy

citizens now began to meet in coffee houses, where

they did business and exchanged reports of the latest news.

The wealthy were now involved in the search for profit, although

with their new wealth they tended to buy country estates and

titles. The “wit” with which young men like Donne had tried

to impress powerful courtiers a century before was now applied in

daily conversation to impress one’s colleagues. The dominant tone

was satire because almost every aspect of traditional

society had become fragile and uncertain, while there was much corruption.

The name “Augustan Age” given to the early 18th century

reflects the sense of new beginnings and increased prosperity that

marked the first years of the Roman Empire, (Augustus was

the first Roman emperor) although England very precisely had no

Augustus ruling it with dictatorial powers. Instead it had a new Horace

(great Augustan poet of satire) in Alexander Pope. His

writing reflects the intense tensions that were at work in him and

the society of his time, between tradition and innovation. In Parliament

these tensions were shown in the division between “Tories”

and “Whigs” as political “parties” began to evolve.

One element of conflict was the difference between “town”

and “country.” The older nobility owned land in the

“shires” and lived as gentry without needing much money;

the newly rich and dynamic class lived in the towns and

cities. Their money was invested to make more money. The values of

the Tory countryside were conservative, nostalgic

for the past, royalist and Anglican. The Whigs

represented the radical new ways of urban capitalism, many

were “non-conformist” (Presbyterian), not nostalgic

but rather upstart and forward-looking.

The disappearance of the court as a focus of power and the

rising importance of the House of Commons, led to a

massive increase in the power of “public opinion” and this

in turn was reflected by increasing public debate of every issue

and policy. The growth of the influence of the press went

hand in had with a realization that journalism was not always

reponsible, that the “news” reported was not always true. Many of

the Augustan concerns sprang from a sense that truth was becoming

the victim of modern finance. Their desire was therefore to educate

people through their writings to think clearly and wisely, so that

they could distinguish the folly and falsehood of modern society

from what was of real value.

The Augustans were people of sharp intelligence who had

been deeply influenced by the developments

in philosophy of the previous 100 years,

beginning with Galileo, Montaigne and Descartes. In

England, Francis Bacon was followed by Thomas Hobbes

(author of Leviathan) and the extremes of Hobbes’s

materialism provoked the work of John Locke and George

Berkeley. This latter, born in Ireland, was close to the

Augustans. At the same time, science (known as natural

philosophy) was developing, with Isaac Newton the

crowning glory. His Principia Mathematica was

published in 1687, the Opticks in 1704, and his

message of the universal harmony sustaining the universe

underlies the optimism of the 18th century’s Rationalism

and Enlightenment.

Alexander Pope (1688-1744)

Pope’s family was Catholic and as a result were

obliged to live outside of London after the events of 1688. He had

a tutor but mostly studied alone. He spent much of his adult life

in Twickenham, up the Thames from London. In his childhood he

contracted a disease which left him stunted, deformed and

hunch-backed, although his head grew to the normal size and his

face was of striking beauty. The double handicap of Catholicism

and physical deformity meant that he was cruelly treated in many

ways and he came to value immensely the people who gave him their

friendship. His closest companion in youth was Jonathan Swift,

who then went to Ireland and later wrote “Gulliver’s Travels.”

Pope’s talents as a poet were accompanied by a sharp desire to chastise

folly. He made his money by translating Homer into

classically dignified “heroic couplets” (the most popular kind of

verse since Denham and Dryden); he made his enemies in many ways,

and wrote poems to vindicate himself. The tone of his poems is

always calm, reasonable, detached, but the satire is sharp and

sometimes extreme.

In his youth, Pope established his reputation

with his Essay on Criticism (1711) and The Rape of the

Lock (a mock heroic poem on a stolen lock of hair). After

the Homer translations were done, the Illiad in 1720, the Odyssey

in 1726, he edited Shakespeare. In later years, following Horace,

he wrote a number of epistles; An Essay on Man (1733-4) is

a philosophical poem in four epistles, which were published

separately. The first three were anonymous, and critics habitually

hostile to Pope acclaimed them, only to be made to look foolish

when the last was published with the poet’s name.

From Epistle 2

Know, then, thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the stoic's pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast;

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reasoning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little, or too much:

Chaos of thought and passion, all confused;

Still by himself abused, or disabused;

Created half to rise, and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled:

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!

The four Moral Essays (1731-5) include an Epistle Of

the knowledge and Characters of Men and the Epistle on

Women. At the same time he published a number of splendid,

free translations of the Satires of Horace, transposing

them to contemporary London. The Dunciad is perhaps his

fiercest satire, a mock-epic that expanded until its final form

was published in 1743.

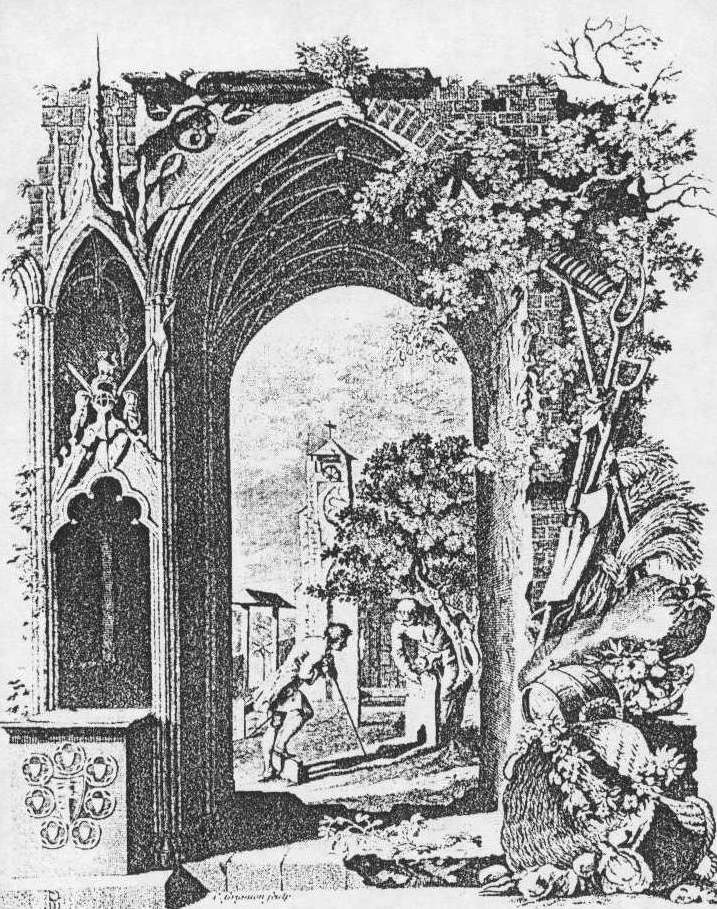

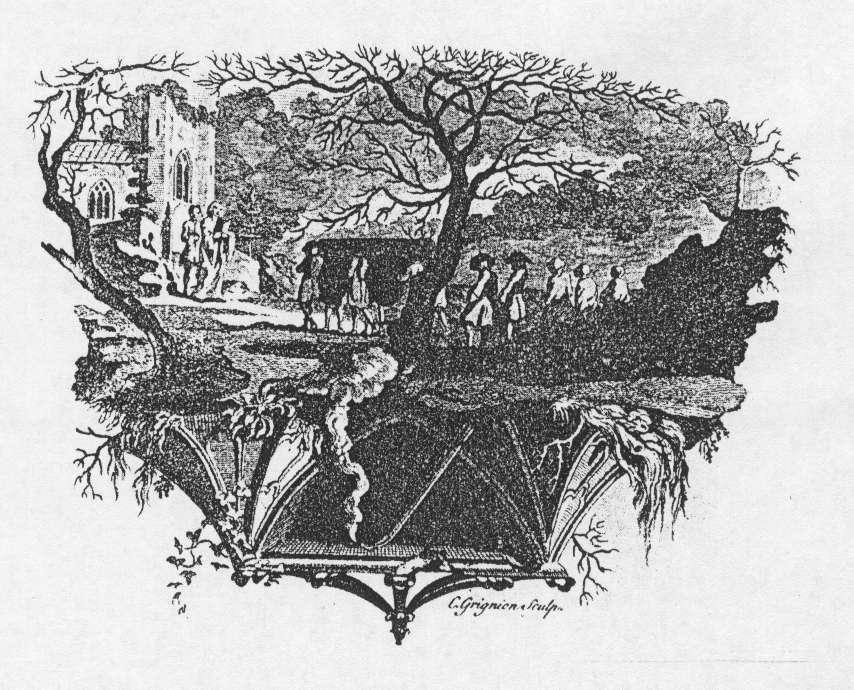

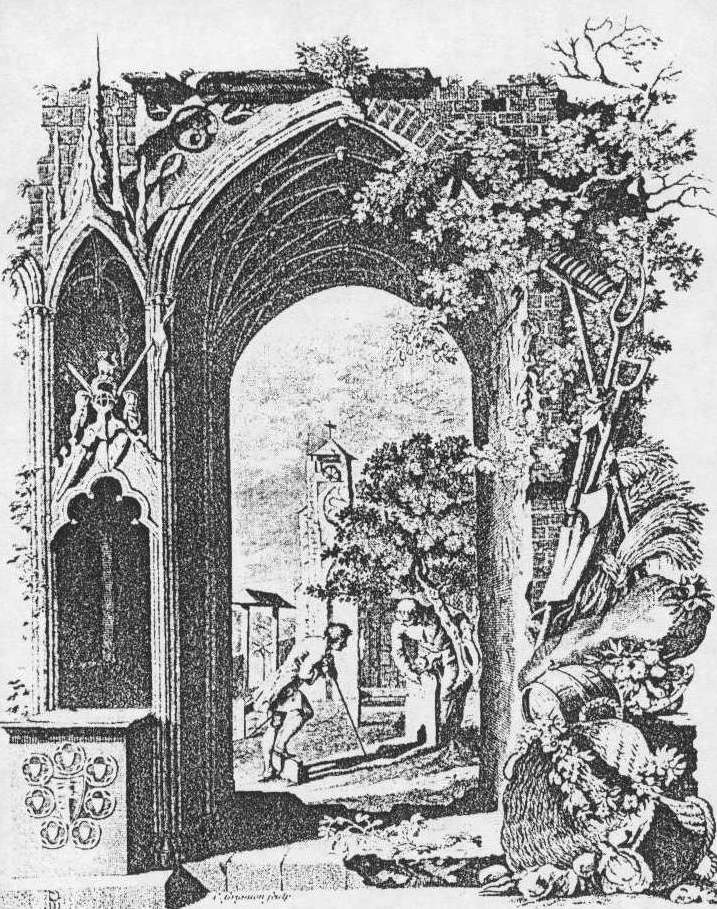

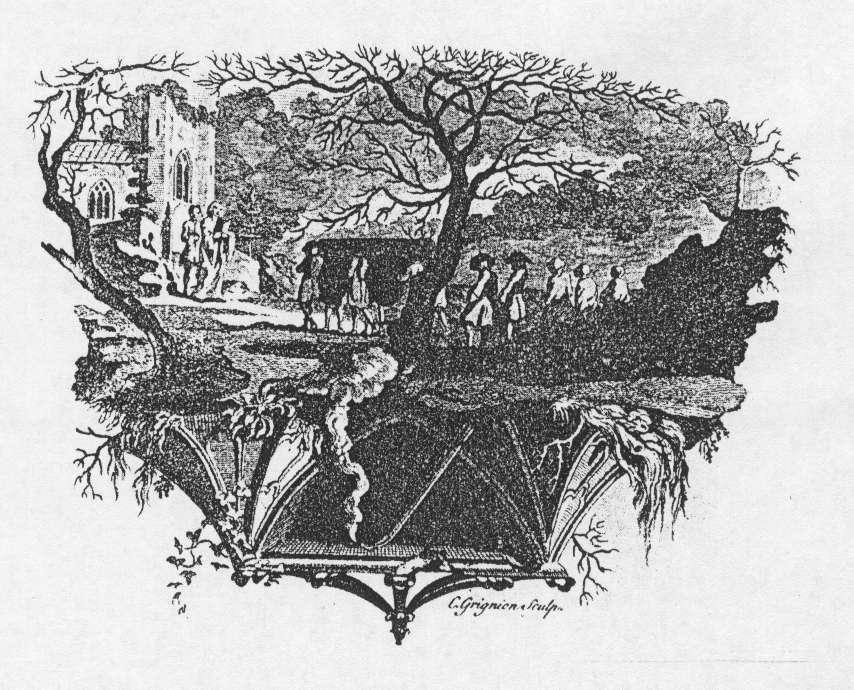

Sensibility before Romanticism

Pope and the other Augustans sometimes seem

utterly intellectual and skeptical; yet their sense of irony,

their awareness of the contradictions that co-exist within

the apparent harmonies of classicism, underlie the birth of the novel

and its development at least as far as Jane Austen. At the same

time, Pope was strongly interested in landscape gardening,

the expoitation of the natural within the artificial, and in this

he was not alone. The Augustan age was marked by a growing

interest in the “picturesque” that was slowly to develop

into a taste for the “Gothic” which begins to be visible in

the mid-18th century’s taste for medieval ruins. Before

Romanticism, among the earliest novels we find a number of “Gothic

novels” set in the middle ages or in medieval buildings.

Nature in itself had been part of

renaissance literature mainly in pastoral poetry. The

first poem to celebrate nature from a new, often Newtonian,

perspective was James Thomson’s The Seasons

(1726-30). Here we begin to find a new sense of the “sublime”

in the evocation of storms. At the same time as Pope was writing

in a satirical, often acid tone about the corruptions of urban

society, Thomson (who was born and educated in Scotland) was

offering readers a completely un-ironic picture of the

appearance of the natural countryside through the different

seasons, seen reflecting Newton's harmony. Yet his diction

is as artificial as that of Pope and later romantics turned

against him. The Seasons remained immensely popular and

long continued to be published.

In art, the English painters of the

18th century produced a vast number of portraits,

corresponding to the wealth of the upper classes. Sir Joshua

Reynolds and John Gainsborough were the most famous

portrait painters. The carcicatures of William Hogarth

were also originally paintings, before being copied as cheap

engravings.

Thomas Gray (1716-1771) lived a very

quiet life. As a young man he was at Eton with Horace Walpole,

who later became one of the first admirers of “the Gothic” and the

author of The Castle of Otranto (1764), the

first Gothic novel. Gray moved to Cambridge in 1742 and

began to write poetry. His small number of works include the Elegy

printed below (1751), by far the most popular and for almost 2

centuries one of the most popular poems in English. He then wrote

The Progress of Poesy and The Bard, both much more

intense and “romantic” with a greater sense of the numinous

and the sublime. He travelled in the Lake District and

Scotland in search of sublime landscpaes and traditional poetry.

Thomas Gray : Elegy written in a Country Churchyard

1. The Curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

2. The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea,

3. The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

4. And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

5. Now fades the glimmering landscape on the

sight,

6. And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

7. Save where the beetle wheels his droning

flight,

8. And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

9. Save that from yonder ivy-mantled

tow'r

10. The moping owl does to the moon complain

11. Of such as, wand'ring near her secret bow'r,

12. Molest her ancient solitary reign.

13. Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's

shade,

14. Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring

heap,

15. Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

16. The rude Forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

17. The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

18. The swallow twitt'ring from the straw-built

shed,

19. The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing

horn,

20. No more shall rouse them from their lowly

bed.

21. For them no more the blazing hearth shall

burn,

22. Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

23. No children run to lisp their sire's return,

24. Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

25. Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

26. Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has

broke:

27. How jocund did they drive their team afield!

28. How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy

stroke!

29. Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

30. Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

31. Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

32. The short and simple annals of the poor.

33. The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,

34. And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er

gave,

35. Awaits alike th' inevitable hour:

36. The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

37. Nor you, ye Proud, impute to These the

fault,

38. If Memory o'er their Tomb no Trophies raise,

39. Where through the long-drawn aisle and

fretted vault

40. The pealing anthem swells the note of

praise.

41. Can storied urn or animated bust

42. Back to its mansion call the fleeting

breath?

43. Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust,

44. Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of

death?

45. Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

46. Some heart once pregnant with celestial

fire;

47. Hands, that the rod of empire might have

sway'd,

48. Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre.

49. But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

50. Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er

unroll;

51. Chill Penury repress'd their noble rage,

52. And froze the genial current of the soul.

53. Full many a gem of purest ray serene

54. The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear:

55. Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

56. And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

(. . . . . . . )

The first

novels

(Click here

for a full account of the development of the English novel)

(Those bolded remain popular today)

Samuel Richardson (1689-1761) 1740 Pamela; 1748 Clarissa

: The History of a Young Lady; 1749 Sir Charles Grandison

Henry Fielding (1707-1754) 1742 Joseph Andrews; 1743

Jonathan Wild the Great; 1749 Tom Jones; 1751 Amelia

Tobias Smollett (1721-1771) 1748 Roderick Random; 1751

Peregrine Pickle; 1771 The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker;

Laurence Sterne (1713-1768) 1760 The Life and Opinions

of Tristram Shandy; 1768 Sentimental Journey

Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774) 1766 The Vicar of Wakefield

Henry Mackenzie (1745-1831) 1771 The Man of Feeling

Horace Walpole (1717-1797) 1765 The

Castle of Otranto

Frances Burney 1752-1840) 1778 Evelina; 1782 Cecilia; 1796

Camilla

Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823) 1794 The Mysteries of Udolpho;

1797 The Italian

"Monk" Lewis (1775-1818) 1796 The Monk

William Godwin (1756-1836) 1794 Caleb Williams

William Beckford (1760-1844) 1786 The Caliph Vathek