The illustrations in this document are from a fifteenth-century manuscript of

the chronicle of Jean Froissart, a contemporary of Chaucer's, and a poet as

well. Froissart, who was French, was usually partisan towards Richard II because

Richard favored a peace treaty with France. The manuscript is owned by the

Bibliotheque Nationale de France,

1338 The beginning of the 100 Years' War

Isabella of France Received at Paris.

England and France had been complexly interwoven ever since the Conquest of England by William I, who set a precedent by leaving his French holdings to his eldest son, Robert, and his English holdings to his second son, William II. English dominion of French territories reached a high point under Henry II, but from the thirteenth century, France began to be successful in restoring French sovereignty to French lands, first during the reign of John, who managed to lose Normandy, and then with the division of the two aristocracies from 1244 with the Decree of the Two Masters. The situation was re-complicated however during the reign of Edward II, who, like his predecessors, married a French princess, Isabelle, daughter of Philip IV. Edward's reign was a troubled one. His magnates became alarmed at the influence of Edward's lover, Piers Gaveston, and exiled Gaveston in 1311, but he was later executed when he attempted to return the following year. Under Edward's rule the English suffered a decisive defeat by the Scots at Bannockburn in 1314, and later languished under the oppressive rule of Edward and a new favorite, Hugh Despencer. Isabelle in the meantime became the lover of Roger Mortimer, and together the two plotted to overthrow Edward, leading an invasion of England in 1326. Edward was imprisoned and no doubt executed.

The Coronation of Edward III

Edward III was only 15 when he succeeded to the throne, yet he managed to avenge his father by executing Roger Mortimer in 1330. He won an important battle against the Scots in 1333 at Halidon Hill and began a lifelong a career of military aggression. In 1338, after the death of his mother's brother, Philip IV, he declared himself king of France, on the basis of his mother's claims, thus beginning the Hundred Year's war. The English had held land in France ever since the reigns of William I's sons, but John had lost Normandy in 1204 (by unwisely divorcing his English wife to marry Isabelle of Angouleme, betrothed to a member of the powerful Lusignan family, and thus giving the French king an excuse to attack Normandy when John refused a summons to appear before him). Edward's ambition was to recover the territories that England had once held in France.

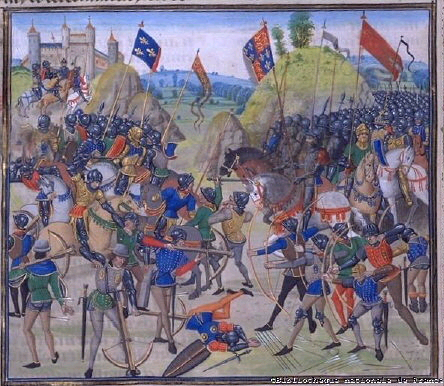

The Battle of Crecy

In 1346, thanks in part to the use of the longbow, the English defeated a much larger mounted French force at Crecy, introducing a period of peace.

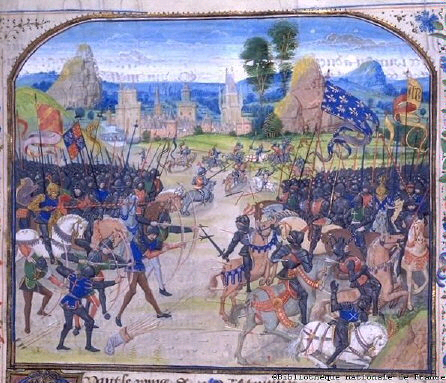

The Battle of Poitiers

In 1355 Edward, the Black Prince, captured Bordeaux which he used as a base to raid and plunder the south of France. In 1356, the English scored their second major victory at Poitiers, where they succeeded in capturing the French king, John. Afterwards, the peace of Bretigny was signed, which was generally favorable to the English. In the 1370's after the accession of King Charles V, the tide of war began to turn in favor of the French. The Black Prince died in 1376, followed by his father in 1377, who was succeeded by his 10-year-old grandson, Richard II. The problem of peace with France was one that dogged Richard's reign, complicated by the fact that wealth from spoil and plunder was an incentive for the military class to keep war alive. Richard's uncle, Thomas of Gloucester, was one of the most determined advocates of war.

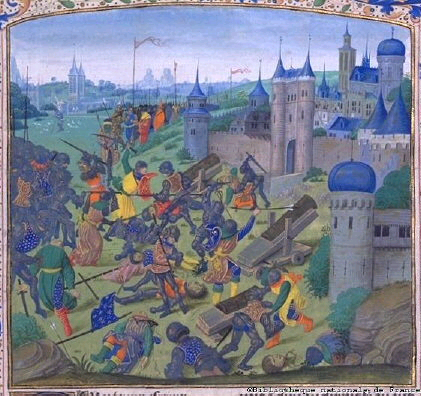

The Battle of Nicropoli

Throughout the fourteenth century, the Western Church was in profound crisis. In 1309, Pope Clement V moved the seat of the Church from Rome to Avignon, France, where the Church came under the influence of the French monarchs. In 1378, the cardinals who had elected Pope Urban VI became dissatisfied with his behavior and sought to annul his election, claiming that it had been made under duress. They withdrew their obedience and elected a new Pope, Clement VII. Urban excommunicated Clement, who returned to Avignon. One result of the crisis in the Western Church was to encourage Muslim aggression in Eastern Europe. The French historian Froissart reports that the Turkish leader Bajazet, who defeated the French at the Battle of Nicropoli, had declared that the Western Church was corrupted by those who should have been its guardians and he was born to accomplish its ruin. He would, he boasted, march to Rome and feed his horse on the altar of St. Peter.

1381 The Peasants' Revolt

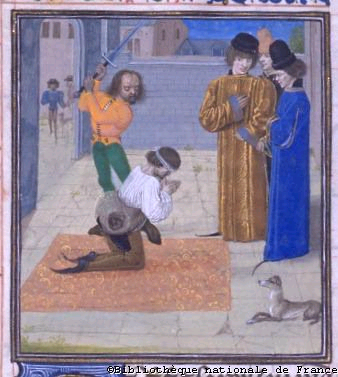

The Death of Wat Tyler

Although the immediate cause of the Rebellion was the imposition of an unpopular poll (head) tax, contributing factors were neglect of administration and justice for warfare, corruption of justice, the recurrent breakdown of law and order. The Rebellion of 1381 began in South-West Essex when a tax commissioner, John Bampton, arrived at Brentwood in Barstable Hundred and was driven from the village. Neighboring villagers also panicked when they heard what had happened and when news spread that the government intended an exemplary punishment, a full-scale revolt ensued. The revolt's most effective leader was Wat Tyler, who led the rebels to Canterbury where Archbishop Sudbury was executed, the sheriff seized, and judicial records burned. The rebels reached London June 10 and requested a meeting with King Richard on June 11. Richard (age 14) met with Wat Tyler on June 14 at Mile End, London and granted collective charters of pardon and freedom from serfdom to the men of Essex and Hertfordshire. On June 14 and 15 the so-called Anonymous Chronicle speaks of 140-160 Flemish textile workers killed. The king met with Wat Tyler again on June 15 at Smithfield who made a series of fantastic demands, including that all lordship be abolished save that of the king, that the goods of the church be given to the parishoners and that there be only one bishop. A scuffle ensued, Tyler was killed, and the king stepped forward, and spoke at the age of fourteen, the culminating speech of his political career. "Your leader is dead. Follow me; I am your leader."

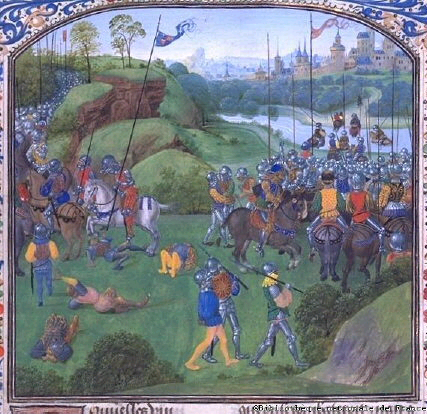

The Battle of Radcot Bridge

In 1386, a group of nobles, jealous of the influence on Richard of certain advisors who were outside the royal circle, forced themselves on the king as a governing council. The following year, however, encouraged by Michael de la Pole, Robert de Vere and others, Richard managed to reassert his prerogative, but afterwards there was an armed uprising by the Duke of Gloucester, the Earl of Arundel, the Earl of Warwick and others who appealed of treason these same advisors. There was a military encounter, known as the Battle of Radcot Bridge, between these forces and Robert de Vere, who had determined to escape to Ireland.

The Flight of Robert de Vere

1387-8 The Merciless Parliament

p>

p>

In 1388, at the initiative of Thomas of Gloucester, Henry, Earl of Derby, Richard of Arundel, Thomas of Warwick, and others, the so-called Merciless Parliament convicted of treason a number of Richard's advisors (many of whom had ties to Chaucer): Simon Burley, John Beauchamp, John Salisbury, Robert de Vere, Michael de la Pole, Nicholas Brembre, James Berners, and Robert Tresilian. Burley, Beauchamp, Salisbury, Berners, Tresilian and others were executed.

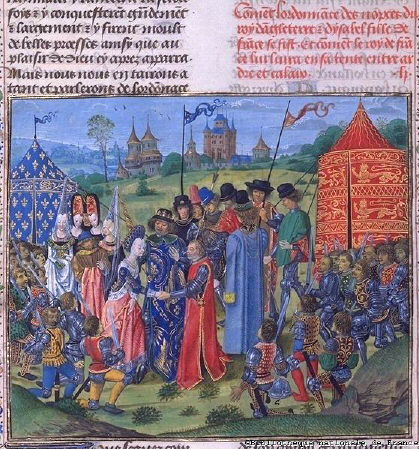

The Marriage of Richard to Isabel of France

In 1396, in order to bring an end to the French wars, Richard married Isabel of France, daughter of King Phillip the VI, who was only 8 years old at the time. The marriage was opposed by Richard's old enemy, Thomas of Gloucester, and indirectly led to Richard's death after he was informed of a plot by Gloucester and others to remove and imprison him. In retaliation, Richard had Gloucester imprisoned and murdered, exiled Henry Bolingbroke, and seized Henry's property when he was out of the way. It was was this course of action that furnished the pretext for the charges of tyranny against Richard and led to his deposition and murder.

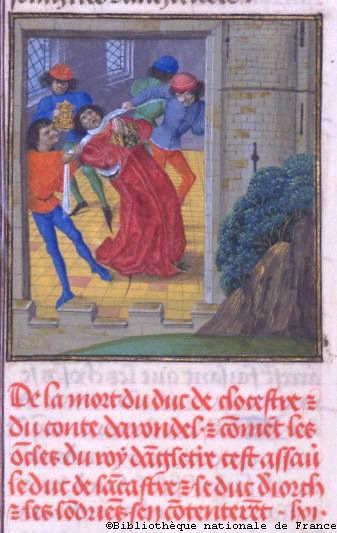

The Death of Gloucester

Gloucester was arrested and put in Mowbray's charge and taken to Calais where he died in mysterious circumstances, by some reports strangled with his bedding as he is portrayed here. Richard called a Parliament and accused those involved in the plot against him of treason, using as a pretext the actions of the Merciless Parliament that had taken place some eleven years previously.

The Challenge of Derby and Mowbray

According to some French chronicles, the Earl of Arundel, Thomas Mowbray, the Earl of Derby and the Duke of Gloucester met in August of 1397 at Arundel on the invitation of the Duke of Gloucester. There they plotted to seize Richard, along with John of Gaunt, and the Duke of York and imprison them forever. Mowbray informed Richard of their intentions, and Richard responded with the arrest of Gloucester and others. Mowbray and Henry Percy, Earl of Derby, mutually accused each other of treason. Henry accused Mowbray of the death of Gloucester and of appropriating money destined to pay the soldiers at Calais while Mowbray accused Derby of treason against the king. Richard banished Derby for ten years and exiled Mowbray forever. Mowbray later died in Venice.

1399 The Arrest of Richard II

Shortly after the exile of Henry Percy, his father, John of Gaunt died, and Richard seized all his properties. Richard also neglected to inform Henry of his father's death. Henry, raised an army, returned to England, and had Richard arrested and imprisoned.

The Abdication of Richard II

Richard supposedly abdicated voluntarily to Henry, although Richard was never seen alive again after his imprisonment.