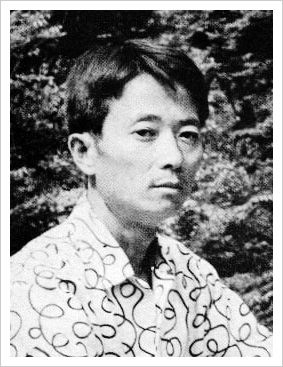

The poet Shin Dong-yeop

(August 18, 1930 – April 7, 1969)

Shin Dong-yeop was born on June 10, 1930, in Buyeo, South Chungcheong Province, the eldest of five children, the other four being daughters. Their father was Shin Yeon-sun and his mother Kim Yeong-hee. In 1944, he graduated from Buyeo Elementary School at the head of his class, then entered Jeonju Normal School, the government covering the cost of housing and tuition fees.

His father taught him to write at the age of six when he saw how calm and talented his son was, buying quantities of books and writing-brushes for him despite their poverty. However, in 1948, Shin Dong-yeop was expelled from the Normal School as a consequence of class boycotts against Syngman Rhee, in particular disagreeing with the South Korean president's land reform policy and inaction on liquidating pro-Japanese assets. In 1949, Shin Dong-yeop came back to his hometown and was appointed a teacher at the elementary school there, but after three days he quit and entered the Department of History at Dankook University. His father, a judicial scrivener, being in straightened circumstances, paid for his tuition by selling fields, so much he respected his son's wish to study.

Trouble began for him when the Korean War broke out in 1950. On July 15, 1950, the People's Army occupied Buyeo and carried out a land reform project, giving Shin Dong-yeop the title of propaganda director for the Democratic Youth League. Shin Dong-yeop was not a communist, but he served in that capacity until the end of September of that year, then left Buyeo when collaborators came under attack and lived a errant life for some time. At the end of 1950, he was drafted into the South Korean National Defense Corps, where he had to face starvation after officers embezzled the money intended for food. Thousands of others died. The National Defense Corps was disbanded on April 30, 1951. It was at this time that he caught liver distoma. Until the end of the Korean War, still only in his early twenties, he narrowly escaped death several times, at the hands of both the North Korean People's Army and the South Korean forces.

After graduating from Dankook University in 1953, he opened a secondhand bookstore in Donam-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, and at that time he met his future wife, In Byeong-seon, whom he married in 1957 on returning to Buyeo. In 1959, he won The Chosun Ilbo annual spring literary contest with “The Talking Ploughman's Earth,” an extended poem written while he was receiving sanatorium treatment for the tuberculosis he had contracted during the war, and made his debut as a writer. He recovered to some extent and started work at Education Criticism Publishers in Seoul. He was actively involved in the “April 19 Revolution” of 1960, as a result of which he is often referred to as the "April Revolution poet" by many writers.

In 1961, he was hired as a teacher for an evening section at Myung-Sung Girls' High School. His most celebrated poem, “Away with the Husk,” was for long one of the top ten poems remembered by Koreans, while his lengthy epic “Geum River,” written in 1967, was adpated as an operetta in 1989 and became the first such work to be performed in both Seoul and Pyongyang. He was only 38 when he died of liver cancer in 1969.

Composing works that see the Donghak Revolution, the Korean Independence Movement and the April 19 Spirit as the essence of Korea’s history, and reject the forces opposing them as the husk of history, he is widely considered to have been the first resistant poet in South Korea, and his work was severely repressed as leftist literature by successive dictatorships.

In 2003, he received posthumously the Silver Medal of Culture from the Government of the Republic of Korea, and the Shin Dong-yeop Literary Museum, established in Buyeo in 2013, has become a major goal of literary tourism.

Poems by Shin Dong-yeop

Translated by Brother Anthony of Taizé

껍데기는 가라

Away with the Husk

좋은 언어

Good Language

산에 언덕에

On Mountains, on Hills

종로5가

Jongno 5ga

산문시(散文詩) 1

Prose Poem 1

진달래 산천

Azalea Landscape

발

Feet

사월은 갈아엎는 달

April Is a Month for Plowing

왜 쏘아

Why Did You Shoot?

누가 하늘을 보았다 하는가

Who Says They Saw the Sky?

빛나는 눈동자

Shining Eyes

풍경

Landscapes

압록강 이남

South of the Yalu River

술을 많이 마시고 잔 어젯밤은

As I Slept after Drinking a Lot Last Night

조국

Motherland

서시(序詩)

Prologue

Geumgang (Geum River) (Extracts)

껍데기는 가라

껍데기는 가라.

사월도 알맹이만 남고

껍데기는 가라.

껍데기는 가라.

동학년(東學年) 곰나루의, 그 아우성만 살고

껍데기는 가라.

그리하여, 다시

껍데기는 가라.

이곳에선, 두 가슴과 그곳까지 내논

아사달 아사녀가

중립(中立)의 초례청 앞에 서서

부끄럼 빛내며

맞절할지니

껍데기는 가라.

한라에서 백두까지

향그러운 흙가슴만 남고

그, 모오든 쇠붙이는 가라.

Away with the Husk

Husk, be gone.

April, let your husk

be gone, may your grain remain.

Husk, be gone;

Let only the shouting

of the Tonghak revolution in Gongju

remain, its husk once gone.

And again, husk, be gone

from this land,

in which a native lad meets his lass,

heart to heart,

free and easy.

They will welcome each other

for a marriage of minds

in the peace hall

of neutrality.

Husk, be gone

from Mount Halla in the south

to Mount Paektu in the north;

may all glinting metals be gone

and only fragrant earth remain.[

좋은 언어

외치지 마세요

바람만 재티처럼 날아가버려요.

조용히

될수록 당신의 자리를

아래로 낮추세요.

그리고 기다려보세요.

모여들 와도

하거든 바닥에서부터

가슴으로 머리로

속속들이 굽이돌아 적셔보세요.

하잘것없는 일로 지난날

언어들을 고되게

부려만 먹었군요.

때는 와요.

우리들이 조용히 눈으로만

이야기할 때

허지만

그때까진

좋은 언어로 이 세상을

채워야 해요.

Good Language

Don't shout.

Only the wind goes flying off like ashes.

Quietly,

make your place

as low as possible.

Then wait,

even if they come all together.

If you do that, start from below,

up to the breast, on up to the head,

then soak, after meandering to the full.

In days gone by, with trivial things

I busily exploited

languages.

A time is coming,

a time when we will talk quietly

with our eyes alone.

But

until then

we have to fill this world

with good language.

산에 언덕에

그리운 그의 얼굴 다시 찾을 수 없어도

화사한 그의 꽃

산에 언덕에 피어날지어이.

그리운 그의 노래 다시 들을 수 없어도

맑은 그 숨결

들에 숲 속에 살아갈지어이.

쓸쓸한 마음으로 들길 더듬는 행인아.

눈길 비었거든 바람 담을지네

바람 비었거든 인정 담을지네.

그리운 그의 모습 다시 찾을 수 없어도

울고 간 그의 영혼

들에 언덕에 피어날지어이.

On Mountains, on Hills

Though I shall never be able to find his lovely face again,

his bright flowers

will bloom on mountains, on hills.

Even though I shall never hear his lovely songs again,

his clear breath

will live on in fields, in forests.

You passerby who follow field paths with a lonely heart.

If your gaze is empty, it may hold the wind.

If the wind is empty, it may hold compassion.

Though I shall never be able to find his lovely form again,

his soul that wept as it went away

may bloom in fields, on hills.

종로5가

이슬비 오는 날.

종로5가 서시오판 옆에서

낯선 소년이 나를 붙들고 동대문을 물었다.

밤 열한시 반,

통금에 쫓기는 군상(群像) 속에서 죄 없이

크고 맑기만 한 그 소년의 눈동자와

내 도시락 보자기가 비에 젖고 있었다.

국민학교를 갓 나왔을까.

새로 사 신은 운동환 벗어 품고

그 소년의 등허리선 먼 길 떠나온 고구마가

흙 묻은 얼굴들을 맞부비며 저희끼리 비에 젖고 있었다.

충청북도 보은 속리산, 아니면

전라남도 해남 땅 어촌 말씨였을까.

나는 가로수 하나를 걷다 되돌아섰다.

그러나 노동자의 홍수 속에 묻혀 그 소년은 보이지 않았다.

그렇지.

눈녹이 바람이 부는 질척질척한 겨울날,

종묘(宗廟) 담을 끼고 돌다가 나는 보았어.

그의 누나였을까.

부은 한쪽 눈의 창녀가 양지쪽 기대앉아

속내의 바람으로, 때 묻은 긴 편지 읽고 있었지.

그리고 언젠가 보았어.

세종로 고층건물 공사장,

자갈지게 등짐하던 노동자 하나이

허리를 다쳐 쓰러져 있었지.

그 소년의 아버지였을까.

반도의 하늘 높이서 태양이 쏟아지고,

싸늘한 땀방울 뿜어낸 이마엔 세 줄기 강물.

대륙의 섬나라의

그리고 또 오늘 저 새로운 은행국(銀行國)의

물결이 뒹굴고 있었다.

남은 것은 없었다.

나날이 허물어져가는 그나마 토방 한 칸.

봄이면 쑥, 여름이면 나무뿌리, 가을이면 타작마당을 휩쓰는 빈 바람.

변한 것은 없었다.

이조(李朝) 오백년은 끝나지 않았다.

옛날 같으면 북간도라도 갔지.

기껏해야 버스길 삼백리 서울로 왔지.

고층건물 침대 속 누워 비료 광고만 뿌리는 거머리 마을,

또 무슨 넉살 꾸미기 위해 짓는지도 모를 빌딩 공사장,

도시락 차고 왔지.

이슬비 오는 날,

낯선 소년이 나를 붙들고 동대문을 물었다.

그 소년의 죄 없이 크고 맑기만 한 눈동자엔 밤이 내리고

노동으로 지친 나의 가슴에선 도시락 보자기가

비에 젖고 있었다.

Jongno 5ga

One drizzly day

beside the traffic lights at Jongno 5ga

an unknown boy grabbed me and asked the way to Dongdaemun.

Half past eleven at night,

innocent among the crowds hurrying to avoid the curfew.

the boy's large, bright eyes

and the wrapper round my lunch box were getting wet.

Maybe he’d just left primary school,

he was holding the new sneakers he’d taken off

while on his back sweet potatoes that had traveled far

were rubbing muddy faces together and getting wet in the rain.

Was his accent that of Songni-san in Boeun, Chungcheongbuk-do,

or that of a fishing village in Haenam in South Jeolla?

I walked as far as the next streetside tree, then looked back,

but there was no sign of the boy, submerged in the flood of workers.

Right.

A soggy winter’s day with wind melting the snow.

As I made my way round the wall of Jongmyo I glimpsed

what might have been his sister,

a prostitute, with one eye swollen,

wearing only her underwear, sprawled provocatively

in a sunny spot, reading a long, grubby letter.

And one day I saw

on a high-rise construction site in Sejong-ro,

one worker carrying a hod of gravel

who had collapsed after hurting his back.

Might he have been the boy’s father?

From high in the sky above the peninsula, the sun streamed down,

three streams on a forehead dripping with drops of cold sweat.

Waves of a continental island nation

and today, that new banking country,

were rolling.

There was nothing left.

Not so much as a single dilapidated earth-floored hovel.

Empty winds sweeping over mugwort in spring,

tree roots in summer, threshing floors in autumn.

Nothing had changed.

The five hundred years of the Yi Dynasty had not ended.

In the old days, people went to Manchuria.

But, now, they take a bus all the way up to Seoul,

where very few people are lying in bed

in high-rise building in leech villages,

or the construction site of buildings

where some kind of impudence will be plotted.

They come here bringing their lunch boxes.

One drizzly day,

an unknown boy grabbed me and asked the way to Dongdaemun.

Night came down on that boy’s innocently big, clear eyes

and in my heart, weary from laboring, my lunch-box wrapper

was getting wet with rain.

산문시(散文詩) 1

스칸디나비아라던가 뭐라구 하는 고장에서는 아름다운 석양 대통령이라고 하는 직업을 가진 아저씨가 꽃리본 단 딸아이의 손 이끌고 백화점 거리 칫솔 사러 나오신단다. 탄광 퇴근하는 광부들의 작업복 뒷주머니마다엔 기름 묻은 책 하이데거 러쎌 헤밍웨이 장자(莊子) 휴가여행 떠나는 국무총리 서울역 삼등대합실 매표구 앞을 뙤약볕 흡쓰며 줄지어 서 있을 때 그걸 본 서울역장 기쁘시겠소라는 인사 한마디 남길 뿐 평화스러이 자기 사무실 문 열고 들어가더란다. 남해에서 북강까지 넘실대는 물결 동해에서 서해까지 팔랑대는 꽃밭 땅에서 하늘로 치솟는 무지갯빛 분수 이름은 잊었지만 뭐라군가 불리우는 그 중립국에선 하나에서 백까지가 다 대학 나온 농민들 트럭을 두대씩이나 가지고 대리석 별장에서 산다지만 대통령 이름은 잘 몰라도 새 이름 꽃 이름 지휘자 이름 극작가 이름은 훤하더란다 애당초 어느 쪽 패거리에도 총 쏘는 야만엔 가담치 않기로 작정한 그 지성(知性) 그래서 어린이들은 사람 죽이는 시늉을 아니하고도 아름다운 놀이 꽃동산처럼 풍요로운 나라, 억만금을 준대도 싫었다 자기네 포도밭은 사람 상처 내는 미사일기지도 탱크기지도 들어올 수 없소 끝끝내 사나이나라 배짱 지킨 국민들, 반도의 달밤 무너진 성터 가의 입맞춤이며 푸짐한 타작 소리 춤 사색(思索)뿐 하늘로 가는 길가엔 황토빛 노을 물든 석양 대통령이라고 하는 직함을 가진 신사가 자전거 꽁무니에 막걸리병을 싣고 삼십리 시골길 시인의 집을 놀러 가더란다.

Prose Poem 1

In a country called Scandinavia or something, a man with a job known as Beautiful Sunset President has come out to the street of department stores holding the hand of his daughter, a flowery ribbon in her hair, to buy a toothbrush. In the back pocket of the working clothes of every coal miner leaving the mine after work, oil-stained books, Heidegger, Russell, Hemingway, Chuang Tzu, and as the Prime Minister, setting off on a vacation trip, queues in front of the ticket window under blazing sunlight in the Central Station’s third-class waiting room, the station master sees that and, opening the door of his office, goes in after leaving as sole greeting a ‘You must be happy.’ Waves rolling from the southern sea to the northern river, flower beds fluttering from the east sea to the west sea, iridescent fountains soaring from the ground into the sky, I've forgotten its name but in that neutral country, whatever its name, where almost all farmers who have graduated from university have two trucks each and live in villas of marble, and although they don't know the president's name, they know perfectly the names of birds, flowers, conductors, playwrights. A land of such intelligence, resolved from the start not to be involved in any kind of gangs, in gun-shooting barbarism, where children do not play at killing people, a land like a flower garden, bountiful in beautiful games, refusing despite offers of billions in gold for their vineyards to allow any missile launch-sites or tank stations that might hurt people to come in, a truly masculine nation, citizens defending audacity, a moonlit night on the peninsula, a kiss in the castle ruins, a mere recollection of hefty threshing sounds and dances, a gentleman bearing the title of President of Sunset, tinged with an ochre glow beside a road to heaven, is on his way along a ten-mile rural path to visit a poet’s house carrying a bottle of makgeolli on the back of his bicycle.

진달래 산천

길가엔 진달래 몇 뿌리

꽃 펴 있고,

바위 모서리엔

이름 모를 나비 하나

머물고 있었었어요

잔디밭엔 장총(長銃)을 버려 던진 채

당신은

잠이 들었죠.

햇빛 맑은 그 옛날

후고구려 적 장수들이

의형제를 묻던,

거기가 바로

그 바위라 하더군요.

기다림에 지친 사람들은

산으로 갔어요

뼈섬은 썩어 꽃죽 널리도록.

남해 가,

두고 온 마을에선

언제인가, 눈먼 식구들이

굶고 있다고 담배를 말으며

당신은 쓸쓸히 웃었지요.

지까다비 속에 든 누군가의

발목을

과수원 모래밭에선 보고 왔어요.

꽃살이 튀는 산허리를 무너

온종일

탄환을 퍼부었지요.

길가엔 진달래 몇 뿌리

꽃 펴 있고,

바위 그늘 밑엔

얼굴 고운 사람 하나

서늘히 잠들어 있었었어요

꽃다운 산골 비행기가

지나다

기관포 쏟아놓고 가버리더군요.

기다림에 지친 사람들은

산으로 갔어요.

그리움은 회올려

하늘에 불붙도록.

뼈섬은 썩어

꽃죽 널리도록.

바람 따신 그 옛날

후고구려 적 장수들이

의형제를 묻던,

거기가 바로

그 바위라 하더군요.*

잔디밭엔 담뱃갑 버려 던진 채

당신은 피

흘리고 있었어요.

Azalea Landscape

A few azalea roots along the roadside

are flowering.

On one corner of a rock

a butterfly, species unknown,

had long been resting.

Throwing your rifle down onto the lawn,

you

fell asleep.

That rock

was precisely the spot

where the enemy generals of late Goguryeo

buried blood brothers

in days of old when sunshine was bright.

People tired of waiting

headed into the mountains,

where their piles of bones had rotted to be scattered as flowers.

You laughed forlornly

as you rolled a cigarette and said that

in the village near the southern sea

you had left behind,

blind relatives at some time or other

were starving.

I came from the sandy orchard

after seeing someone’s ankles

in Japanese working shoes.

Shattering hillsides ablaze with flesh-flowers,

all day long

shells were fired off.

A few azalea roots along the roadside

were flowering,

and in the shadow of a rock

someone with a lovely face

was fast asleep, chilled and killed.

A plane flew

over a flowery mountainside,

poured down machine-gun fire, then left.

People tired of waiting

went up into the mountains

where their longing went whirling up

to set the sky on fire,

and their piles of bones rotted

to be scattered as flowers.

The place where enemy generals of late Goguryeo

in days of old when the wind was warm

buried blood brothers

was precisely that rock.

Throwing your cigarette pack onto the lawn,

you were shedding

blood.

발

백화점 층계를

비 뿌리는 오후, 내려오던 다리.

스커트 속을

한가한 미풍(微風)은 왕래하고 있었지만

깜장 힐 위 중력을 주면서

가벼운 오뇌 속삭이고 있었다.

언제부터 시작되어

너희들의, 걸음은

어데까지 가고 있는 걸까.

희끗희끗 눈발 날릴 때

중학교 원서 접수시키러 구멍가게 골목

종종치던 종아리.

송화강(松花江) 끝에서도 왔다

구름 같은 흙먼지,

아세아 대륙 누우런 벌판을

군화 묶고 행진하던 발과 다리,

지금은 어데 갔을까.

꽃 피는 남국(南國)

부드러운 모래밭 해안에 배가 닿으면

부지런히 신무기를 싣고 뛰어내리던

이유 없는 발톱.

보리밭을 밟고 있었다,

물방아 위에도 있었다,

해수욕장에선

그 싱싱한 허벅다리 사이로

태양이 지고.

깎아놓은 유리창 위 비는 내리고

넘치는 가슴덩이

찰떡같이 몸부림은 흐느낄 때,

노래하고 싶었다.

뱀같이, 열반(涅槃)같이, 경련하다 급기야

나른하게 죽어 뻗던 그 흰 다리.

다리,

너를 보면

빛나는 여름

우렛소리 들으며 산맥을 넘던

낭만,

나리꽃 동산에 전쟁은 가고

채소밭 가운데 섰던

국적 모를, 두개의 무릎뼈에도

눈은 없었다.

어머니를 불렀지.

집행장 문 앞

엉버티었지, 안 가겠다고

있는 힘 다하여 안간힘 하며

마지막 땀 흘리던

연약한 다리여.

밀회(密會)도 실어 날랐지,

착취로 기름진 아랫배,

음모로 반짝이던 골통들도 실어 날랐지,

그리고 눈은 없어도

링 위에선 멋있게 그놈의 턱을 걷어찼다.

다들 남의 등 어깨 위로 올라갔지만

아직 너만은 땅을 버리지 못했구나

넌 우리네 조국

넌 하층구조

내 한(恨)을 실어오고 또 실어간다.

백악관 귀빈실 주단 위에도 있었어,

대영제국 궁전 금의자 아래에도 있었어,

종로3가 창녀(娼女) 아랫목에도 있었지,

발바닥

코 없는 너를 보면

눈물이 날밖에.

강산은 좋은데

이쁜 다리들은 털 난 달러들이

다 자셔놔서 없다.

일어서야지,

양말 신은 발톱 흉물 떨고 와

논밭 위 세워논, 억지 있으면

비벼 꺼야지,

열번 부러져도 그 사랑

발은 다시 일으켜 세우기 위하여 있는 것,

발은 인류에의 길

멎고 멎음을 증명하기 위하여 있는 것,

다리는, 절름거리며 보리수 언덕 그 미소(微笑)를 찾아가려 나왔다.

다시 전화(戰火)는 가고

쓰러진 폐허

함박눈도 쏟아지는데

어데서 나왔을까, 너는 또

뚜벅뚜벅 걸어오고 있었다.

Feet

Legs descending a department store’s stairs

one rainy afternoon.

Inside her skirt

an idle breeze was circulating

but as she imposed gravity on her black heels

whispering a slight agony.

Starting from when,

how far might your steps

be going?

When snow falls white,

calves hurriedly walking down alleys with small stores

to file applications for junior high school.

They even came from the end of the Songhua River.

Dust like clouds,

your feet and legs that marched across the yellow plains

of continental Asia tied in army boots,

where are you now?

Leaping down,

diligently bearing new weapons,

the moment the boat touched the soft sandy beach

of flowering southern lands.

Those aimless toes

were trampling down the barley fields.

They were on the water mill, too.

On the beach

between those fresh thighs

the sun was setting.

When rain runs down peeled windows,

overflowing chests

sob, in struggles like soft rice cake,

I longed to sing.

Those white legs finally stretch out idly,

twitch like snakes, like Nirvana.

Legs,

when I look at you,

hearing thunder, from beyond the mountains

in glorious summer,

romance,

The war on the gardens of lilies had ceased

and the two knee bones of unknown nationality

that stood in the middle of the vegetable garden

had no eyes.

I called for Mother.

Feeble legs

where the last sweat ran

standing firm, resisting with all their might

before the door of the execution yard.

You bore off a secret love,

a belly greasy with exploitation,

carrried off skulls sparkling with intrigue,

and even without eyes

kicked smartly that bastard’s chin in the ring.

Everybody climbed onto the shoulders of others

but you alone haven't given the land up yet.

You are our homeland,

you are the lower levels,

bringing my bitterness and carrying it off again.

You were on the silks and satins of the White House VIP Room,

and under the gold chairs in the British royal palace,

as well as the place of honor of a Jongno 3 ga whore,

soles

when I see you without any nose

tears simply flow.

Mountain landscapes are good

but pretty legs, because of hairy dollars,

have all vanished.

You must stand up,

shaking off the monstrosity of toes wearing socks.

Standing on the rice fields, if there is resistance

it should be stubbed out,

even if broken ten times, that love’s

feet are there in order to stand up again,

feet are the way to humanity,

there in order to prove stagnation,

legs, set off limping to find the linden-tree hill, that smile.

Once again the flames of war have vanished,

on fallen ruins

snow came pouring down

and you too were coming

swaggering from somewhere.

사월은 갈아엎는 달

내 고향은

강 언덕에 있었다.

해마다 봄이 오면

피어나는 가난.

지금도

흰 물 내려다보이는 언덕

무너진 토방 가선

시퍼런 풀줄기 우그려넣고 있을

아, 죄 없이 눈만 큰 어린것들.

미치고 싶었다.

사월이 오면

산천은 껍질을 찢고

속잎은 돋아나는데,

사월이 오면

내 가슴에도 속잎은 돋아나고 있는데,

우리네 조국에도

어느 머언 심저(心底), 분명

새로운 속잎은 돋아오고 있는데,

미치고 싶었다.

사월이 오면

곰나루서 피 터진 동학의 함성,

광화문서 목 터진 사월의 승리여.

강산을 덮어, 화창한

진달래는 피어나는데,

출렁이는 네 가슴만 남겨놓고, 갈아엎었으면

이 균스러운 부패와 향락의 불야성 갈아엎었으면

갈아엎은 한강 연안에다

보리를 뿌리면

비단처럼 물결칠, 아 푸른 보리밭.

강산을 덮어 화창한 진달래는 피어나는데

그날이 오기까지는, 사월은 갈아엎는 달.

그날이 오기까지는, 사월은 일어서는 달.

April Is a Month for Plowing

My hometown was

on a hill above a river.

When spring came year by year

poverty blossomed.

Still now

on the hill overlooking white water,

off to the border of ruined hovels

crushing stems of dark grass into their mouths,

ah, innocent little children with eyes that alone are big.

I felt I would go crazy.

When April comes

the crust of nature is torn open,

inner leaves sprout,

when April comes

inner leaves sprout from my breast, too,

and in our homeland

in some remote inmost heart, clearly

new inner leaves sprout,

I felt I would go crazy.

When April comes

the shouts of Donghak rebels bleeding in Gongju,

April's victory acclaimed at Gwanghwamun.

Covering the hills, bright

azaleas bloom,

leaving only your throbbing heart, if only you would plow,

plow up this infected corruption, nights of pleasure,

and if only barley were sown

on the plowed up shores of the Han River

ah, with waves like silk, green barley fields.

Covering the hills, bright azaleas bloom

and until that day comes, April is a month for plowing,

until that day comes, April is a month for rising up.

왜 쏘아

눈이 오는 날

소년은 쓰레기통을 뒤졌다.

바람 부는 밤

만삭의 임부는

철조망 곁에 쓰러져 있었다.

그리고 눈이 갠 아침

그 화창하게 맑은 산과 들의

은빛 강산에서

열두살짜리 소년들은

어제 신문에서 읽은 동화(童話) 얘길 재잘거리다

저격받았다.

나는 모른다.

그 열두살짜리들이 참말로

꽁꽁 얼어붙은 조그만 손으로

자유를 금 그은 철조망 끊었는지 안 끊었는지.

나는 모른다

그 철조망들이

맨발로 된장찌개 말아 먹은 소년들에게

목숨을 강요해서까지

필요한 것인지 아닌지는.

다만 나는 안다

지금은 이중으로

철조망이 쳐져 있고

검은 창고가 서 있지만

그 근처 양지바른 언덕은

우리 어렸을 때만 해도

머리에 흰 수건 두른 아낙들이

안방 이야길 주고받으며

햇빛에, 목화단 콩깍지들을 말리던 곳이다.

그리고 또 나는 안다

지금은 낯선 얼굴들이

얕보는 휘파람으로 왔다 갔다 하지만

그 근처 양지바른 언덕은

우리 어렸을 때만 해도

토끼몰이 하던 아우성으로

씨름놀이 하던 함성으로

밤낮을 모르던 박첨지네 동산이다.

쓰레기통을 뒤져

깡통 꿀꿀이죽을 찾아 먹는 일

나도 이따금은 해봤다

눈사태 속서 총 겨냥한

낯선 병정의 호령을 듣고

그 퍽퍽한 눈 속을

깊이깊이 빠지면서 무릎 이겨 기던

그 소년의 마음을 나는 안다.

꿰진 뒤꿈치로

사지 늘어트려

국수가닥 깡통을

눈 속에 놓치던

그 마음을 나는 안다.

아기 밴 어머니가

배가 고파, 애들을 재워놓고

집을 빠져나와

꿀꿀이죽을 찾으려던 그 마음을,

고요한 새벽 흰 눈이 쌓인 그 벌판에서의

외로운 부인의 마음을

나는 안다.

왜 쏘아.

그들이 설혹

철조망이 아니라

그대들의 침대 밑까지 기어들어갔었다 해도,

그들이 맨손인 이상

총은 못 쏜다.

왜 쏘아.

우리가 설혹

쓰레기통이 아니라

그대들의 판자(板子) 안방을 침범했었다 해도

우리가 맨손인 이상

총은 못 쏜다.

쏘지 마라.

솔직히 얘기지만

그런 총 쏘라고

박첨지네 기름진 논밭,

그리고 이 강산의 맑은 우물

그대들에게 빌려준 우리 아니야.

벌 주기도 싫다

머피 일등병이며 누구며 너희 고향으로

그냥 돌아가주는 것이 좋겠어.

솔직히 얘기지만

이곳은 우리들이

백년 오백년 천년을 살아온

아름다운 땅이다.

솔직히 얘기지만

이곳은 우리들이 천년 이천년

울타리 없이도 콧노래 부르며 잘 살아온

아름다운 강산이다.

Why Did You Shoot?

One snowy day

a boy was rummaging through trash cans.

One windy night

a mother at full term

lay fallen by a barbed wire fence.

And one morning when the snow had stopped

amidst the silvery landscape

of bright, clear mountains and fields

twelve-year-old boys

were chattering about the children’s tale read in yesterday’s newspaper

when they were shot at.

I do not know

if those twelve-year-old boys

with their frozen little hands

really broke the barbed wire fence

drawing a line across freedom or not.

I do not know.

if the barbed-wire fences

were necessary or not

for boys who ate bean paste soup with bare feet,

to the point of losing their lives.

But I do know.

Now the barbed-wire fences

are hanging double

and a black warehouse is standing there but

the sunny hillsides nearby were the place where,

women with white towels on their heads

exchanged inner talk,

drying cotton pods in the sun

when we were young.

And again I know.

Now strange faces are roaming around

with disparaging whistles

and the sunny hillsides nearby,

when we were young,

were the hillocks of nobleman Park Cheom-ji’s family,

alive day and night

with the shouts of people coursing hares

and cheering wrestling matches.

I too sometimes tried

rummaging through trashcans

in search of cans with left-over scraps to eat.

I know what those boys felt

on hearing the commands of unknown soldiers

aiming guns from within an avalanche,

plunging deep into the crisp snow,

crawling on their knees.

I know their feelings as they stretched their limbs

with torn heels

to hook up a can of noodles in the snow

but failed.

I know

the feelings of a pregnant mother who,

feeling hungry, after putting the children to bed,

leaves the house

intent on finding swill to eat,

I know the heart of that lonely woman

out in fields deep in white snow at dawn.

Why did you shoot?

Even if they had crawled under your beds

instead of barbed wire fences,

seeing that they had only their bare hands,

no guns could shoot them.

Why did you shoot?

Even if we had invaded your plank bedrooms

instead of trash cans,

we had only our bare hands,

no guns could shoot us.

Don’t shoot.

To be honest,

the fertile fields of nobleman Park Cheom-ji,

this land’s clear wells,

are not ceded to you

for such shooting.

I hate to give punishments.

First-class Private Murphy, or whoever,

you'd best just go back home.

To be honest

This is the beautiful land

where we have lived

for one hundred years, five hundred years,

a thousand years.

To be honest

this is the beautiful land of rivers and hills

where we have been living well,

singing along without any fences

for a thousand years, two thousand years.

누가 하늘을 보았다 하는가

누가 하늘을 보았다 하는가

누가 구름 한 송이 없이 맑은

하늘을 보았다 하는가.

네가 본 건, 먹구름

그걸 하늘로 알고

일생을 살아갔다.

네가 본 건, 지붕 덮은

쇠항아리,

그걸 하늘로 알고

일생을 살아갔다.

닦아라, 사람들아

네 마음속 구름

찢어라, 사람들아,

네 머리 덮은 쇠항아리.

아침저녁

네 마음속 구름을 닦고

티 없이 맑은 영원의 하늘

볼 수 있는 사람은

외경(畏敬)을

알리라

아침저녁

네 머리 위 쇠항아릴 찢고

티 없이 맑은 구원(久遠)의 하늘

마실 수 있는 사람은

연민을

알리라

차마 삼가서

발걸음도 조심

마음 아무리며.

서럽게

아 엄숙한 세상을

서럽게

눈물 흘려

살아가리라

누가 하늘을 보았다 하는가,

누가 구름 한 자락 없이 맑은

하늘을 보았다 하는가.

Who Says They Saw the Sky?

Who says they saw the sky?

Who says they saw a clear sky

without a single cloud?

What you saw were thick clouds

and you lived a whole lifetime

mistaking them for the sky.

What you saw was an iron pot

covering the roof

and you lived a whole lifetime

mistaking that for the sky.

Wipe away, everyone,

the clouds from your heart.

Tear apart, everyone,

the iron pot covering your head.

You who, morning and evening,

wipe away the clouds from your heart

can see the clear, eternal, spotless sky,

will experience awe and respect.

You who, morning and evening,

tearing apart the iron pot covering your head,

drink of the immaculate, perennial sky,

Will experience

compassion,

refraining completely,

careful of each step,

lowering the heart,

Sadly,

ah, sadly,

shedding tears,

You will live

in the solemn world.

Who says they saw the sky?

Who says they saw a clear sky

without a single cloud?

빛나는 눈동자

너의 눈은

밤 깊은 얼굴 앞에

빛나고 있었다.

그 빛나는 눈을

나는 아직

잊을 수가 없다.

검은 바람은

앞서 간 사람들의

쓸쓸한 혼을

갈가리 찢어

꽃 풀무 치어오고

파도는,

너의 얼굴 위에

너의 어깨 위에 그리고 너의 가슴 위에

마냥 쏟아지고 있었다.

너는 말이 없고,

귀가 없고, 봄〔視〕도 없이

다만 억척만 쏟아지는 폭동을 헤치며

고고(孤孤)히

눈을 뜨고

걸어가고 있었다.

그 빛나는 눈을

나는 아직

잊을 수가 없다.

그 어두운 밤

너의 눈은

세기(世紀)의 대합실 속서

빛나고 있었다.

빌딩마다 폭우가

몰아쳐 덜컹거리고

너를 알아보는 사람은

당세에 하나도 없었다.

그 아름다운,

빛나는 눈을

나는 아직 잊을 수가 없다.

조용한,

아무것도 말하지 않는,

다만 사랑하는

생각하는, 그 눈은

그 밤의 주검 거리를

걸어가고 있었다.

너의 빛나는

그 눈이 말하는 것은

자시(子時)다, 새벽이다, 승천(昇天)이다.

어제

발버둥치는

수천수백만의 아우성을 싣고

강물은

슬프게도 흘러갔고야.

세상에 항거함이 없이,

오히려 세상이

너의 위엄 앞에 항거하려 하도록

빛나는 눈동자.

너는 세상을 밟아 디디며

포도알 씹듯 세상을 씹으며

뚜벅뚜벅 혼자서

걸어가고 있었다.

그 아름다운 눈.

너의 그 눈을 볼 수 있은 건

세상에 나온 나의, 오직 하나

지상(至上)의 보람이었다.

그 눈은

나의 생(生)과 함께

내 열매 속에 살아남았다.

그런 빛을 가지기 위하여

인류는 헤매인 것이다.

정신은

빛나고 있었다.

몸은 야위었어도

다만 정신은 빛나고 있었다.

눈물겨운 역사마다 삼켜 견디고

언젠가 또다시

물결 속 잠기게 될 것을

빤히, 자각하고 있는 사람의.

세속된 표정을

개운히 떨어버린,

승화된 높은 의지 가운데

빛나고 있는, 눈

산정(山頂)을 걸어가고 있는 사람의,

정신의

눈

깊게. 높게.

땅속서 스며나오듯 한

말 없는 그 눈빛.

이승을 담아버린

그리고 이승을 뚫어버린

오, 인간정신미(美)의

지고(至高)한 빛.

Shining Eyes

Your eyes

were shining

before night’s deep face.

I still

have not forgotten

those shining eyes.

A black wind

tore to shreds

the lonely souls

of those gone before,

billowing as bellowed flowers.

Waves

came pouring down forever

on your face,

on your shoulders, on your breast.

With no words,

no ears, no sight,

aloof, you make your way

through billions of surging riots,

walking

open-eyed.

I still

have not forgotten

those shining eyes

On that dark night

your eyes

were shining

inside the century’s waiting room.

Heavy rain was pouring down

over each building

and at that time there was not one person

who recognized you.

I have still not forgotten

those beautiful,

shining eyes

Quiet,

saying nothing,

simply loving,

thinking, those eyes

went walking along

that night’s carcass streets.

What your shining

eyes said was

midnight, dawn, ascension.

Yesterday,

bearing thousands of millions

of squirming cries,

the river

went flowing sadly.

Eyes shining,

not resisting the world,

but rather in order for the world

to resist before your dignity,

you trample the world

biting the world as if biting a grape,

you went swaggering along

all alone.

Being able to see those beautiful eyes,

your eyes,

was the one, supreme reward

for me in the world.

Together with my life

those eyes

survived inside my fruit.

In order to possess such light

humanity goes wandering on.

The mind

was shining.

Even though the body was gaunt,

still the spirit was shining.

The eyes of someone clearly aware

that every sad history,

once swallowed and endured,

will one day again be submerged in the waves

Shining,

lightly casting off

any worldly expression

amidst sublimated high wills.

Someone walking on mountaintops,

his mind’s eyes,

deeply, highly,

as if seeping from the ground,

without words, such a gaze.

Ah, supreme light

of the beauty of the human mind

engulfing this life,

piercing through this life.

풍경

쉬고 있을 것이다.

아시아와 유럽

이곳저곳에서

탱크부대는 지금

쉬고 있을 것이다.

일요일 아침, 화창한

토오꾜오 교외 논둑길을

한국 하늘, 어제 날아간

이국(異國) 병사는

걷고.

히말라야 산록(山麓),

토막(土幕) 가 서성거리는 초병은

흙 묻은 생고구말 벗겨 넘기면서

하얼빈 땅 두고 온 눈동자를

회상코 있을 것이다.

순이가 빨아준 와이셔츠를 입고

어제 의정부 떠난 백인 병사는

오늘 밤, 사해(死海) 가의

이스라엘 선술집서,

주인집 가난한 처녀에게

팁을 주고.

아시아와 유럽

이곳저곳에서

탱크부대는 지금

밥을 짓고 있을 것이다.

해바라기 핀,

지중해 바닷가의

촌 아가씨 마을엔,

온종일, 상륙용 보트가

나자빠져 뒹굴고.

흰 구름, 하늘

제트 수송편대가

해협을 건너면,

빨래 널린 마을

맨발 벗은 아해들은

쏟아져나와 구경을 하고.

동방으로 가는

부우연 수송로 가엔,

깡통 주막집이 문을 열고

대낮, 말 같은 촌색시들을

팔고 있을 것이다.

어제도 오늘,

동방대륙에서

서방대륙에로,

산과 사막을 뚫어

굵은 송유관은

달리고 있다.

노오란 무꽃 핀

지리산 마을.

무너진 헛간엔

할멈이 쓰러져 조을고

평야의 가슴 너머로.

고원의 하늘 바다로.

원생의 유전지대로.

모여 간 탱크부대는

지금, 궁리하며

고비 사막,

빠알간 꽃 핀 흑인촌.

해 저문 순이네 대륙

부우연 수송로 가엔,

예나 이제나

가난한 촌 아가씨들이

빨래하며,

아심아심 살고

있을 것이다.

Landscapes

They must be resting.

Here and there

in Asia and Europe

tank brigades must now

be resting.

Sunday morning, in sunny

Tokyo suburbs,

the foreign soldiers

that flew through Korean skies yesterday

must be walking.

In Himalayan foothills

sentries standing on guard beside dugouts,

peeling shared sweet potatoes,

must be recalling

eyes they left behind in Harbin.

A white soldier who left the Uijeongbu base yesterday

wearing a shirt washed by a Korean girl,

tonight, beside the Dead Sea

gives a tip to a poor girl

from the family of the owner

of an Israeli bar.

Here and there

in Asia and Europe

tank brigades must now

be cooking food.

In the village of a rural girl

where sunflowers bloom

on a Mediterranean beach,

all day long, landing craft

tumble and roll.

White clouds, sky

as jet carriers in formation

cross the straits,

and in villages with laundry hanging

bare-footed children

come pouring out to watch.

Beside the smoky transport route

heading eastward

a tavern built of cans may be open

in broad daylight, selling horse-like

village girls.

Yesterday and today,

from the lands of the East

to the lands of the West,

through mountains and deserts

a thick pipeline

goes running.

In a Jiri-san village.

where yellow radish flowers bloom

in a ruined barn

an old woman has fallen down, dozes.

Tank brigades that have passed

over the breasts of plains,

over highland sky seas,

primeval oil fields.

now, reflecting

In the Gobi Desert,

in black people’s villages where flowers bloom red,

in the land of Suni’s family where the sun is setting,

beside smoky transport routes,

in olden days and now

poor village girls

must be washing clothes,

living nervously.

압록강 이남

폭격으로 쓰러진 집터에선

능굴이가 원통히 울었다.

하늘 멀리서 제트기들이 번갯불처럼 지나다니고

어데선가 송장이 썩는다

낯익은 얼굴들이 무더기로 쓰러져

썩는 내음새가 국화 향기보다 진하다.

다 같이 압록강 이남에서 사는

조선 사람들이었다.

가는 곳마다

산골에서도 평야에서도

도시에서도, 마을은 모두 폐허로 화하고

젊은 아들딸들은 이편으로 저편으로

총들을 얽매고 없어져버리었다.

가다가다 살아남은 마을엔

질병과 기아와 상잔의

어두운 살풍만이 배회했다.

평화를 사랑하는 조국

조선 사람아

너는 어찌하여

너는 어찌하여 다 같이 조선말을 하는 얼굴 속에서

원수를 찾아내어야 하며

형제와 애인의 인연에

탄약을 쟁여야만 하느냐

그리하여 제각기

자기 남편 편이 이겨 오기를

자기 오빠 편이 이겨 오기를

얼마나 많이

얼마나 많은 사람들의 가슴이

빌고 있을 것인가.

애인아 누나야

조선 사람아

너는 누구를 위하여 누구에게

어제도 오늘도 방아쇠를 당기는 것이냐.

삼천리강토를 침략하는 자 누구냐

어느 놈이

아, 어느 놈이

조선을 저의 방패로 삼으려 하는 것이냐……

오늘도

폭격으로 쓰러진 집터에선

South of the Yalu River

In a house bombed to ruins

a snake wept bitterly.

In the distance, jets fly like lightning

and a corpse is rotting somewhere

familiar faces fall in droves,

the smell of rotting is stronger than chrysanthemums.

We were all people of Joseon

living together south of the Yalu River.

No matter where you went,

in mountains, on plains,

cities, villages, all had turned into ruins

while youthful sons and daughters,

taking up guns, had disappeared this way and that.

Going further, in the surviving villages

dark gusts of disease, famine, conflict

alone roamed.

People of Joseon,

peace-loving motherland,

why,

why do you feel obliged to find enemies

in faces that all speak the Joseon language?

Why do you feel obliged to pile up ammunition

against the relationship between brothers and lovers?

Thus each one,

so many,

so many people’s hearts are praying

that her husband’s side will win,

that her brother’s side will win.

Lover, sister,

inhabitant of Joseon,

for whom, at whom

are you pulling the trigger, yesterday and today?

Who is invading our lovely land?

What wretch,

ah, what wretch

is trying to make Joseon their shield?

Still today,

in a house bombed to ruins.

술을 많이 마시고 잔 어젯밤은

술을 많이 마시고 잔

어젯밤은

자다가 재미난 꿈을 꾸었지

나비를 타고

하늘을 날아가다가

발 아래 아시아의 반도

삼면에 흰 물거품 철썩이는

아름다운 반도를 보았지.

그 반도의 허리, 개성에서

금강산 이르는 중심부엔 폭 십리의

완충지대, 이른 바 북쪽 권력도

남쪽 권력도 아니 미친다는

평화로운 논밭.

술을 많이 마시고 잔 어젯밤은

자다가 참

재미난 꿈을 꾸었어.

그 중립지대가

요술을 부리데.

너구리새끼 사람새끼 곰새끼 노루새끼들

발가벗고 뛰어노는 폭 십리의 중립지대가

점점 팽창되는데,

그 평화지대 양쪽에서

총부리 마주 겨누고 있던

탱크들이 일백팔십도 뒤로 돌데.

하더니, 눈 깜박할 사이

물방개처럼

한 떼는 서귀포 밖

한 떼는 두만강 밖

거기서 제각기 바깥 하늘 향해

총칼들 내던져 버리데.

꽃피는 반도는

남에서 북쪽 끝까지

완충지대,

그 모오든 쇠붙이는 말끔히 씻겨가고

사랑 뜨는 반도,

황금이삭 타작하는 순이네 마을 돌이네 마을마다

높이높이 중립의 분수는

나부끼데.

술을 많이 마시고 잔

어젯밤은 자면서 허망하게 우스운 꿈만 꾸었지.

As I Slept after Drinking a Lot Last Night

As I slept after drinking a lot

last night

I had a funny dream.

As I went flying through the sky

on a butterfly’s back,

I saw Asia’s peninsula beneath my feet,

a beautiful peninsula

surrounded on three sides with white foam.

At the waist of that peninsula, its center,

from Gaesong as far as the Diamond Mountains

a so-called buffer zone, ten li wide,

peaceful fields where neither Northern forces

nor Southern forces operated.

As I slept after drinking a lot

last night

I had a funny dream.

That sanctuary

was magical,

a sanctuary ten li wide

where baby raccoons, human babies, baby bears, baby roe deer,

all went leaping, naked

and it was gradually expanding,

on either side of that peace zone

the tanks with gun muzzles aimed at each other

all turned one hundred and eighty degrees.

Then, in the blink of an eye,

like water beetles,

one group off the southernmost point at Seogwipo,

one group off the northernmost point on the Tumen River,

each threw their guns away

toward the sky.

The flowering peninsula,

from down south to farthest north

was all a buffer zone,

all the ironware washed away,

a peninsula awash with love,

in every village threshing golden ears,

fountains of neutrality

rose fluttering.

As I slept after drinking a lot last night

I simply dreamed a pointlessly funny dream.

조국

화창한

가을, 코스모스 아스팔트 가에 몰려나와

눈먼 깃발 흔든 건

우리가 아니다

조국아, 우리는 여기 이렇게 금강 연변

무를 다듬고 있지 않은가.

신록 피는 오월

서부사람들의 은행(銀行) 소리에 홀려

조국의 이름 들고 진주 코걸이 얻으러 다닌 건

우리가 아니다

조국아, 우리는 여기 이렇게

꿋꿋한 설옥(雪獄)처럼 하늘을 보며 누워 있지 않은가.

무더운 여름

불쌍한 원주민에게 총 쏘러 간 건

우리가 아니다

조국아, 우리는 여기 이렇게

쓸쓸한 간이역 신문을 들추며

비통을 삼키고 있지 않은가.

그 멀고 어두운 겨울날

이방인들이 대포 끌고 와

강산의 이마 금 그어 놓았을 때도

그 벽(壁) 핑계 삼아 딴 나라 차렸던 건

우리가 아니다

조국아, 우리는 꽃 피는 남북평야에서

주림 참으며 말없이

밭을 갈고 있지 않은가.

조국아

한번도 우리는 우리의 심장

남의 발톱에 주어본 적

없었나니

슬기로운 심장이여,

돌 속 흐르는 맑은 강물이여.

한 번도 우리는 저 높은 탑 위 왕래하는

아우성소리에 휩쓸려본 적

없었나니.

껍질은,

껍질끼리 싸우다 저희끼리

춤추며 흘러간다.

비 오는 오후

버스 속서 마주쳤던

서러운 눈동자여, 우리들의 가슴 깊은 자리 흐르고 있는

맑은 강물, 조국이여.

돌 속의 하늘이여.

우리는 역사의 그늘

소리 없이 뜨개질하며 그날을 기다리고 있나니

조국아,

강산의 돌 속 쪼개고 흐르는 강물, 조국아.

우리는 임진강변에서도 기다리고 있나니, 말없이

총기로 더럽혀진 땅을 빨래질하며

샘물 같은 동방의 눈빛을 키우고 있나니.

Motherland

In bright autumn

it was not we who came thronging

where cosmos flowers rose beside the asphalt,

waving blind flags.

Motherland, aren’t we here, on Geumgang roadsides

trimming radishes?

In May full of fresh greenery,

it was not we who, bewitched by the sounds of westerners’ banks

frequented them with our country's name,

hoping to obtain pearl nose rings.

Motherland, aren’t we here like this

lying gazing up at the sky like upright Mt. Seorak?

In sultry summer,

it was not we who went to shoot at wretched natives.

Motherland, aren’t we here like this

in small whistle stops holding newspapers,

swallowing back our grief?

On remote, dark winter days,

even when foreigners came dragging cannons

and drew lines on our nation’s landscape,

it was not we who took that wall as an excuse and set up another country.

Motherland, aren’t we in the flowery plains of South and North

enduring starvation in silence,

plowing the fields?

Motherland,

we have never once

delivered our hearts

to others’ claws.

Wise heart!

Clear stream flowing over stones!

We have never once been swept away

by shouts coming and going above that high tower.

While husk

fights with husk, then ends up

dancing and flowing.

Sad eyes glimpsed in a bus

one rainy afternoon!

Clear river flowing deep in our hearts,

Motherland!

Heaven hidden in stones!

We are knitting the shade of history

without a word, waiting for that day to come.

Motherland!

Rivers splitting stones and flowing through this land, Motherland!

We are waiting for you beside the Imjin River, without a word,

washing soil made filthy by firearms

cultivating oriental eyes like flowing springs.

서시(序詩)

아담한 산들 드믓드믓

맥을 끊지 않고 오간

서해안 들녘에 봄이 온다는 것

것은 생각만 해도, 그대로

가슴 울렁여 오는 일이다.

봄이 가면 여름이 오고

여름이 오면 또 가을

가을이 가면 겨울을 맞아 오고

겨울이 풀리면 다시 또

봄.

농사꾼의 아들로 태어나

말썽 없는 꾀벽둥이로

고웁게 자라서

씨 뿌릴 때 씨 뿌리고

거둬들일 때 거둬들일 듯

어여쁜 아가씨와 짤랑짤랑

꽃가마나 타 보고

환갑잔치엔 아들딸 큰절이나

받으면서 한 평생 살다가

조용히 묻혀가도록 내버려나

주었던들

또, 가욋말일지나, 그러한 세월

복 많은 가인(歌人)이 있어

봉접풍월(蜂蝶風月)을 노래하고

장미에 찔린 애타는 연심을 읊조리며

수사학이 어떠니 표현주의가 어떠니

한단들 나 역 모르는 분수대로

그 장단에 맞추어 어깨춤이라도

추었을 것이다.

그러나 나는 원자탄에 맞은 사람

태백줄기 고을고을마다

강남 제비 돌아와 흙 물어 나르면

솟아오는 슬픔이란 묘지에 가 있는

누나의 생각일까.....?

산이랑 들이랑 강이랑

이뤄 그 푸담한 젖을 키우는

울렁이는 내 산천인데

머지않아 나는 아주

죽히우러 가야만 할 사람이라는

것이라.

잘 있으라.

해가 뜨나 해가 지나 구름이 끼던

두번 다시 상기하기 싫은

인종(人種)의 늦장마철이여

이러한 노래 나로 하여

처음이며 마지막이게 하라

진창을 노래하여 그 진창과 함께

멸망해 버려야 할 사람이

앞과 뒤를 헤쳐 세상에

꼭 하나뿐 필요했던 것이다.

그러면.....

두고 두고, 착한 인간의 후손들이여

이 자리에 가는 길

서낭당 돌을 던져

구데기.

그런 역사와 함께 멸망한 나의

무덤, 침 한번 더 뱉고

다시 보지 말아져라

Prologue

Neat mountains scattered around, telling

that spring is coming to the fields beside the West Sea

without interrupting the pulse,

the mere thought is enough

to make my breast heave.

Once spring leaves, summer comes,

summer comes, then autumn,

once autumn leaves, winter comes

and when winter withdraws spring comes

again.

Born the son of a farmer,

I grew up tidily

a trouble-free blockhead,

sowing when it’s time to sow,

and harvesting when it’s time to harvest.

Having married a pretty lady

borne in a jingling flowered palanquin,

and received deep bows from sons and daughters

for my sixtieth birthday, after living my life,

may I leave

and be quietly buried.

Incidentally, I imagine that

there may be some blessed poet

to sing of beautiful nature with bees and butterflies,

celebrate fretting loving hearts pricked by roses,

and when people brag about rhetoric or expressionism or whatever,

according to my due,

I would swing my shoulders

keeping time to the tune.

But I am a victim of an atom bomb,

and as swallows return from the South,

fill their beaks with mud, in every part of the Taebaek range,

sorrow comes surging up. Is it because I miss my sister

who has gone to the cemetery?

With mountains and fields and rivers

working together, it is my heaving landscape

producing that rich milk,

I am someone

who will soon have to die.

Farewell,

late rainy season of race,

always cloudy whether the sun rises or sets,

never to be recalled again

May such a song be for me

the first and last.

Celebrating mire and with that mire

only one who must be destroyed

pushing back and forth to the world

was needed.

Then.....

for ever and ever, you descendants of good human beings.

On the way to this place,

toss a stone at the village shrine for good luck.

A maggot.

Spit once more on my grave,

I who fell with such history,

and don't look again

Geumgang (Geum River) (Extracts)

1

Back when we were children

in a hill village of yellow clay laid bare--

borne along on grandmother's back,

my sister and I

often heard the Blue Bird Song.

When creepers blazed red on each fence and wall and

sorghum heads stood high along the sides of fields,

shouts to scare the birds away could be heard on every side.

Oiyoh! Hwuoi!

Once the Japanese cop's cycle with its tinkling bell

had vanished into the distance,

we would wait beside our clay hovel

with racing hearts

for the old peddler woman who taught us her songs.

Seya, seya, p'arangseya...

Bird, bird, blue bird...

do not land in the green pea patch.

If the pea blossom falls

the pea-jelly merchant will go weeping away.

I'm not so sure but in those days

they used to say: If you sing that song

the acupuncture man will whisk you away.

The name has changed now, but

when midday came, a cannon boomed out beneath the sky:

'Let those who worked a lot take a lot to eat,

Let those who did not work eat nothing at all,

Ohoo...,' it said.

On the hill at Kilatt'i,

as we gleaned for grains of bean or rice,

a formation of planes would go flying across the sky

and every time, my mother, with a troubled face

would seize my hand

and hurry me along the field path.

In those days some of the people who had experienced

those great events, were still living in this world;

their tales used to send my heart racing

and I intend to tell you some of them now.

Sometimes they wanted to sow seeds of their stories,

in memories that went scurrying from early morning

to the village hills and fields like carefree pups.

The seeds of those tales

would sprout leaves, and branches,

then at last, one autumn, blossom profusely.

Could they ever have imagined that?

That was why, in snow-swept midwinter

huddled at the warmest spot of the room

where bean-cakes were kept warm under blankets

and in midsummer's suffocating dog days, sitting beneath

the parched village tree, on one branch of which

Sunni's mother hanged herself, they cautiously used to talk,

whisking away cicada songs with their fans,

to us snot-nosed kids

as we sat scratching our bellies,

our belly-buttons bare.

2

We have seen heaven.

In April 1960,

rending the clouds that were crushing history,

we saw the face of Eternity.

Your face,

that shone for one brief moment,

was our innermost

heart.

Scooping up an armful of heaven's waters

in 1919 we all

washed our faces clean.

In 1894 or so

even in stones and tree stumps,

your faces were all heaven.

Heaven,

you shone bright for a moment then were veiled,

yet every year the flowers

filled the whole landscape.

Sun and harvest and love and labour.

On holidays, limping along in a mountaineer's cap,

I would visit the East Sea,

with its brilliant sandy shores,

or Indian back alleys where pottery was fired.

But they couldn't be found

in the outside world. Bowls, meat,

were nowhere to be found

in the outside world.

Your faces

that had shone for a moment

were Eternity's sky,

our infinitely

deep hearts.

(...)

Scene 8

Ha-nui

limped

a little with one foot.

When he was three

he was thrown out

into Kim the Clerk's yard.

The sound of the gate opening and shutting,

the rough rasping sound of a rolling gourd,

dry grass flying here and there,

when the cockrel

in the big house crows far away,

on and on, no regard for the time,

at such moments, without doubt,

starving hordes in search of tree-roots,

the bark of pines, early sprouting shepherd's-purse,

mugwort roots,

will spread white

like dried radish leaves

over hills and fields,

a farmhand

spreading the ashes from some house

over the barley fields in the broad plains

smothered in white ash

will be shaking his head and sneezing.

Surely,

and more.

On the hill along the river

with flowering reeds flying,

a woman bearing a bundle of clothes,

skirts flying,

must still be waiting for the ferryboat.

Two rocks stand face to face.

Ha-nui

was reared by Tol-soi, the farmhand

of Kim the Clerk's house, who had taken him in.

The three-year-old

went hungry

every day.

There were no soy-bean cakes

laid to keep warm on the heated floor.

That was the day

the great Master Chong who lived in Seoul

was due at the house of Kim the Clerk.

All the villagers, young and old, had been mobilized

to level the road during the past month,

and were busily preparing to receive him.

For all the villagers

were the serfs of the ones with money.

Hungry Ha-nui

lay weeping.

His nose against the floor,

he was sorrowfully weeping,

sorrowful to exhaustion.

'The rascals never do as they're told,'

in raging fury, shouting orders to the old head-servant Yu,,

Kim the Clerk stormed into the servant's room in his shoes

and tossed the weeping child out into the yard

where he fell into the pigsty.

Perhaps the old Sam-shin women, guardians of childbirth,

caught him?

his ankle bone simply stuck out more

while his crying stopped,

he sat up

scratching his head with one hand.

Ha-nui

was wrapped in the apron of old woman Cho,

and from that day

he was brought up by her;

she lived in the valley at the back of Puso Mountain.

Old woman Cho's husband had been exiled

for some vague sedition

in the days of King Kwanhae and died there,

a supreme gentleman-scholar, whose eyes

were so pure he could commit no crime:

does such a man have to be forced out

like a pearl in pigs-swill?

In the year Ha-nui turned twelve

he lost old woman Cho.

For nine years she filled the mind of the little scholar,

reading him dozens of volumes

of Chinese classics and Buddhist scriptures.

No one knew anything about

Ha-nui's father.

One rainy day, a woman had appeared

in front of Tol-soi the farmhand, soaked to the skin,

had entrusted him with something wrapped in cotton

and vanished again.

'Ask nothing about this child's

ancestors. Take care of it

until I come again.

I will not forget your kidness,

even if I should never return.

His name is Ha-nui.

His family name is Shin.'

Turning her head aside,

the woman had laid the cotton bundle

and a few coins on the floor of the room,

then vanished into the rain.

The baby's hand

was clasping a tiny ornamental silver bell,

scarcely bigger than bean.

As he grew up,

Ha-nui cared for Tol-soi

like a father.

And that mysterious ornamental silver bell

scarcely bigger than a bean

never left him either.

Scene 9 (extract)

Who says that they have seen the sky?

Who says that they have ever seen the sky

clear without one single cloud?

What you have seen is dark clouds

that you have taken for the sky

-- you have kept on living.

Sweep away, human kind,

the clouds within your hearts.

By morning and night,

sweep away the clouds within your hearts,

and you will see

Eternity's sky spotless and clear,

and you will bring knowledge

of awe.

Take the utmost care,

be careful even in walking,

keep your hearts serene;

sorrowfully,

ah, in this solemn world,

you will live

sorrowfully.

Who says that they have seen the sky?

Who says that they have ever seen the sky

clear without one single shred of cloud?