Bethell, Hulbert, Gale and the Epic Stories of Two

Pagodas

The Wongak-sa Pagoda

Wongak-sa Pagoda is a twelve metre

high ten-storey marble pagoda in the center of Seoul, South

Korea. It was constructed in 1467 to form part of

Wongak-sa temple, that King Sejo had founded two years before on

the site of an older Goryeo-period temple, Heungbok-sa.

"Won'gak-gyeong" is the Korean name of a Buddhist sutra, 圓覺經 The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment

or Complete Enlightenment which King Sejo had

found deeply meaningful, perhaps because his conscience was

tormented by having had his young nephew, the child king

Danjong, deposed in 1455 and then executed (like many of his

ministers) in 1457. The temple was destined to produce elaborate

copies of the Wongak sutra as a work of merit in atonement for

the way King Sejo had come to the throne. The temple was

closed and turned into a kisaeng house by Sejo's great-grandson,

the deposed king known as Yeonsan-gun (1476 – 1506, r.

1494-1506, deposed because of madness), and under his successor,

King Jungjong (1488 – 1544, r.1506–1544), the site was turned

into government offices. The pagoda and a memorial stele

commemorating the foundation of Wongak-sa alone survived. The

site of the temple was later occupied by houses. During the

Imjin War (Japanese invasion) of the 1590s, the top portion of

the pagoda was pulled down and lay on the ground at the foot of

the pagoda until it was replaced by American military engineers

in 1947.

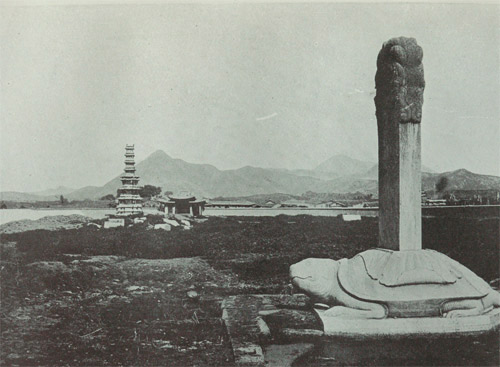

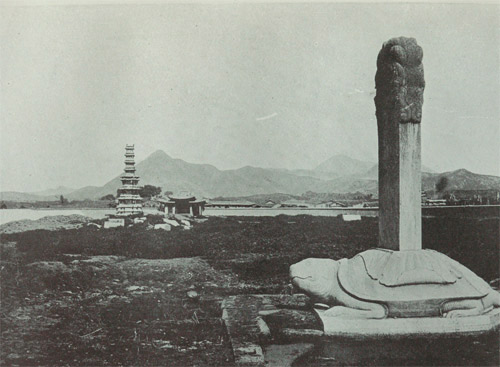

The Pagoda surrounded by houses, from Percival Lowell's "Choson:

The Land of the Morning Calm" (1886)

The site of Wongak-sa (now Tapgol Park) after the demolition of

the houses occupying the site by John McLeavy Brown in 1897

The pagoda in the 1920-30s with the topmost section standing

beside it

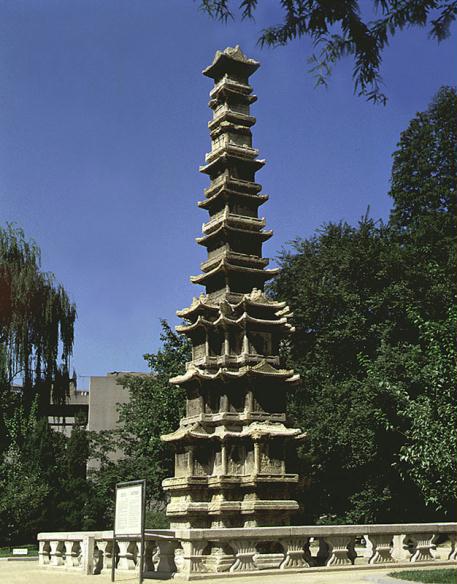

The Wongak Pagoda in Seoul's Tapgol Park before it was enclosed in

glass.

The inscribed stone recording the foundation of Wongak-sa

In 1915, the scholarly missionary James Scarth Gale published in the

Royal Asiatic Society Korea Branch's Transactions Vol. VI, part II:1-22 a very

important paper on “The Pagoda of Seoul.”

He seems to have been the first person in modern times to date

correctly the pagoda and explain its relationship with another

pagoda, which it resembles closely, the older Ten-Storied Pagoda of

Gyeongcheon-sa. He had been given an ancient rubbing of the

inscription on the by then illegible memorial stone (stele)

recording the establishment of Wongak-sa (temple) by King Sejo in

1465 and his paper includes a translation of that account.

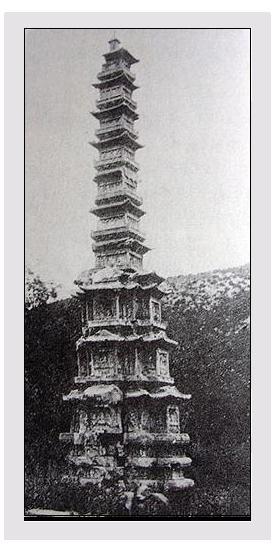

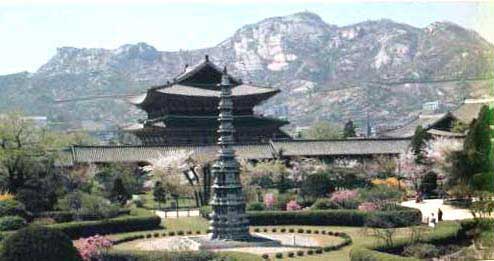

The Ten-Storied

Pagoda of Gyeongcheon-sa

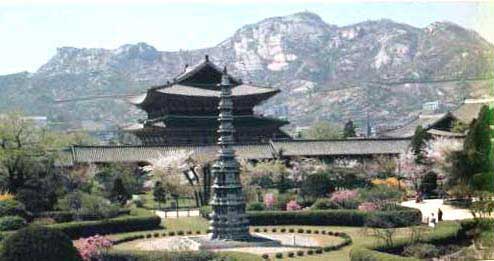

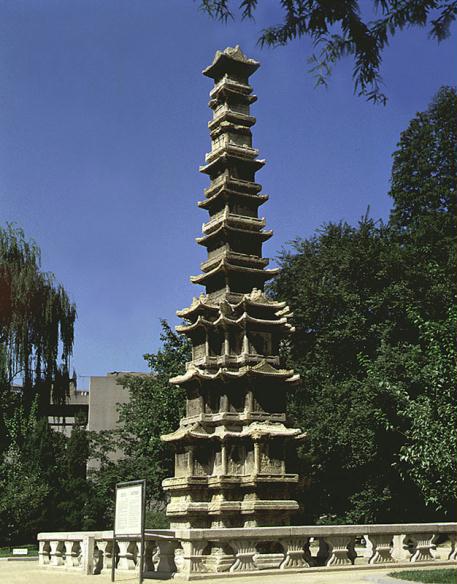

The Ten-Storied Pagoda of Gyeongcheon-sa in the National Museum of

Korea at present

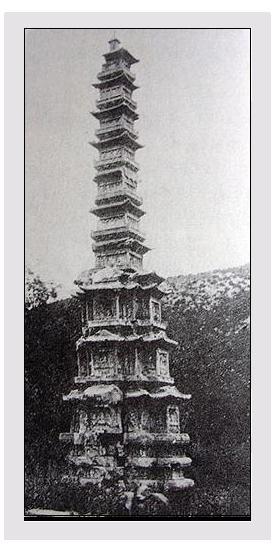

The Ten-Storied Pagoda of Gyeongcheon-sa in 1904

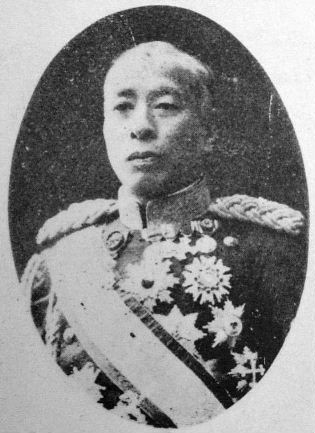

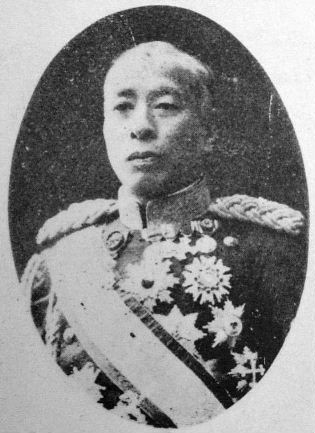

Tanaka Mitsuaki

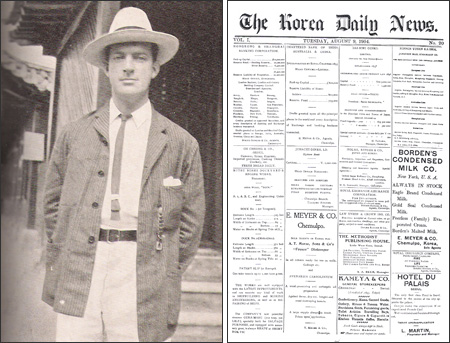

Ernest T. Bethell

Ernest T. Bethell and Homer Hulbert come into the story because they

wrote newspaper articles to denounce the theft of the pagoda.

Ernest T. Bethell was born in England in 1872. Still a youth, he

went to work with his uncle in Japan in 1888. In 1904, at the start

of the Russo-Japanese War, he moved to Korea as correspondent for a

British newspaper. He denounced Japanese atrocities in his reports,

and since the paper’s policy was pro-Japanese, he was dismissed. He

remained in Korea, where he established the Korea Daily News and also

launched a Korean-language newspaper the Daehan Maeil Sinbo. These were both strongly

pro-Korean and anti-Japanese. The British government was favorable

to Japan, so Bethell was tried twice by a British consular court in

Seoul for sedition and violation of public order. First, he was

ordered to pay a 300-pound bond as a guarantee of his good behavior.

Yet he continued his attacks on the Japanese. On June 15, 1908 he

was sentenced to spend three weeks in the British gaol in Shanghai.

After serving his term, Bethell returned to Seoul and boldly resumed

publication of the Korea Daily

News. In April 1909 he fell victim to his heavy smoking and

drinking life-style, dying surrounded by friends on May 1. Hundreds

of Koreans accompanied his funeral. An anti-Japanese epitaph in

Korean was defaced soon after it was erected, then restored after

Liberation in 1945.

Bethell's grave in Seoul

The news of the theft of the Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda soon reached

Seoul. Bethell wrote about it in his newspapers. Homer Hulbert (then

in the US) made the facts known by articles in the Japan Chronicle, and then in

the New York Post and

from there the news spread across the globe. A rather garbled

account even reached a

newspaper in rural New Zealand. But nothing happened in the

following years, while Japan completed the annexation of Korea in

1910. The episode and its sequel is covered at some length in F. A.

McKenzie’s

Korea’s Fight for Freedom

(1920):

The organ of the Residency-General

in Seoul, the Seoul Press,

made the best excuse it could. "Viscount Tanaka," it said, "is a

conscientious official, liked and respected by those who know him,

whether foreign or Japanese, but he is an ardent virtuoso and

collector, and it appears that in this instance his collector's

eagerness got the better of his sober judgment and discretion."

But excuses, apologies, and regrets notwithstanding, the Pagoda

was not returned.

He was wrong. The pagoda had been returned to Seoul in 1918 but

having been damaged in its travels, it lay in pieces in

crates. Today the National Museum of Korea and other Korean

sources claim that this return was solely the direct result of

Bethell’s and Hulbert’s press campaigns. This might not, however,

really be the case. Ten years had passed, Bethell was dead, Hulbert

had left Korea for good long before. Why was it returned at that

time?

Sekino

Tadashi

Sekino Tadashi

Sekino Tadashi (1867-1935) was a professor in the Architecture

Department of Tokyo University. He was the first Japanese art

historian and architect sent to Korea in 1902, to serve as an

architectural historian and the main recorder of Korean antiquities.

Hyung Il Pai has described how ancient Korean remains were carefully

preserved, studied, recorded and registered as part of Japan's state

cultural properties as Kokuho (imperial treasures) as part of their

imperial cultural policy to incorporate the Korean peninsula, its

ancient history and its people as part of their ancestral homelands

(Nissen dosoron). Korea's ancient relics and remains were thus

reclaimed as "Proto-Japanese".

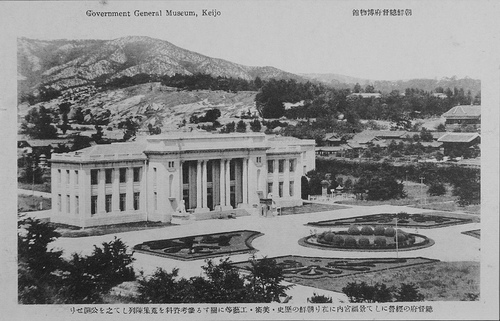

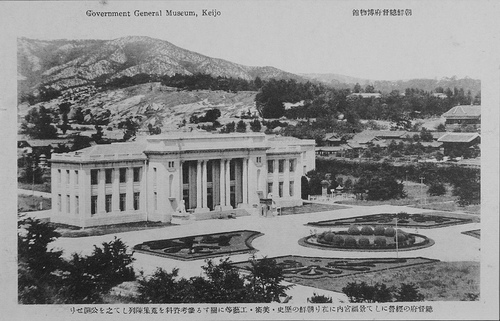

The newly built Art Gallery / Museum

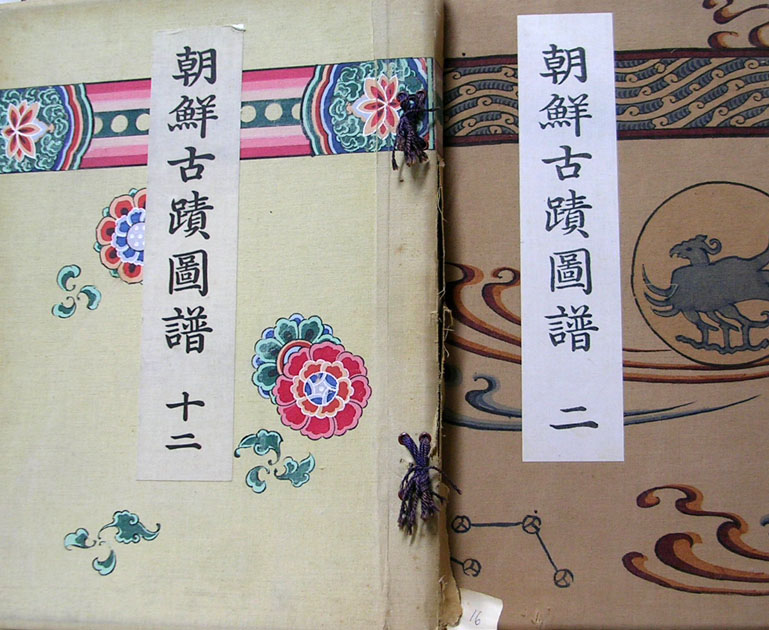

In 1913, Sekino Tadashi began work on the first volume of the

"Chosen koseki zufu" (朝鮮古蹟圖譜) series (Album of ancient sites

and monuments), fifteen magnificent volumes of photos and drawings

of ancient Korean objects and sites published 1915-1935. This and

other publications by him were the origin of the present list of

Korean National Treasures. A

complete set of images of every volume can be seen here

(change the final number to view each volume 1 - 15)

Then the “Chosen Sotokufu (National Treasures) Museum” (aka the

Government-General Museum) was established in Gyeongbokkung in 1915.

The permanent museum was originally built as an art gallery on the

site of the demolished Jaseondang in the Donggung, the Crown

Prince’s Compound, as part of the Chosen Product Promotion

Exhibition held September 11 to October 31st, 1915 to

commemorate the fifth year of annexation. Then it became a museum

when the exhibition ended and in 1918 pagodas and sculptures from

abandoned palaces and temple ruins began to be exhibited in front of

this museum at the recommendation of Sekino Tadashi. That would best

explain why the Japanese brought the pagoda back. Another pagoda

brought back from Japan for similar reasons in 1915 can still be

seen in the grounds of Gyeongbok-gung behind the National Palace

Museum.

The Museum with an ancient relic in front of it

As noted above, James S. Gale wrote about the Wongak-sa Pagoda in a

paper that he presented at a meeting of the RASKB on February 5,

1915, published in Transactions

Volume VI, Part 2. He begins the paper by quoting words he

attributes to Sekino Tadashi:

“The pagoda stood originally within

the enclosure of Wun-gak Temple. It is precisely the same in

shape as the pagoda that stood on Poo-so Mountain in front of

Kyung-ch’un Temple, Poo’ng-tuk County, which dates from the close

of the Koryu Dynasty. Its design may be said to be the most

perfect attainment of the beautiful. Not a defect is there to be

found in it. As we examine the details more carefully, we find

that the originality displayed is very great, and that the

execution of the work has been done with the highest degree of

skill. It is a monument of the past well worth the seeing. This

pagoda may be said to be by far the most wonderful monument in

Korea. Scarcely anything in China itself can be said to compare

with it. The date of its erection and its age make no difference

to the value and excellence of it.”

In his paper, Gale establishes that the Wongak-sa Pagoda was made in

imitation of the Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda, and erected in 1466. Sekino

Tadashi’s words (no source for them is indicated) apply equally to

both the original Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda, which he has obviously

seen, and the later copy. If Sekino Tadashi wrote like that about

the Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda, surely he would have done everything

possible to bring it back from Japan to house in the new museum? It

duly returned to Korea from Japan in 1918, to be housed in the new

museum, and there it remained, damaged and in fragments, until it

was restored and re-erected in the garden in front of it in 1960.

The Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda was erected in Gyeongbok-gung gardens in

1960

Damaged by acid rain, it was removed and today it is safely housed

inside the National Museum. There, rather than admit that the

Japanese Sekino Tadashi arranged for its return, the plaque before

it gives all the credit to the campaigns of Bethell and Hulbert more

than ten years before. It is significant that Gale notes twice in

his paper about the Wongak-sa Pagoda that the Gyeongcheon-sa pagoda

had been taken to Japan a few years before. He nowhere indicates

that he regrets that fact, or that he hopes for its return. There

was clearly no continuing campaign for its return alive in Korea in

1915.