...previous

page

Making tea in Korea

After the loss of Korea's tea culture in the

14th century, tea trees continued to grow wild in the southern

regions, especially on the lower slopes of Chiri mountain.

These self-propagated bushes provided the leaves used by those

few people still aware of their value. Tea does not grow north

of Chonju and not on every kind of soil to the south. In recent

years additional bushes have been planted on the slopes of

Chiri-san, and other southern hills, but without the creation of

large artificial tea plantations. The finest tea is that grown

in complete harmony with nature and with limited use of

fertilisers or insecticides.

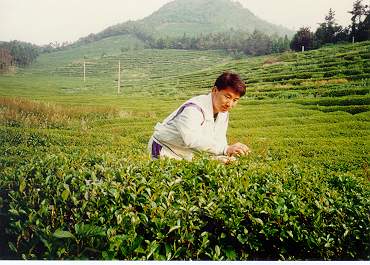

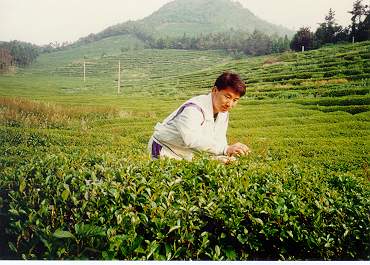

Tea plantations

Tea plantations of a more intensive kind, with the bushes

planted in neat rows and operated on an industrial scale, have

been established in various areas, the most important being

those found in Posong near Kangjin; other large industrial

tea-plantations can be found on the slopes of Wolch'ul-san, also

in the south-west, and and in the island of Cheju-do. The Posong

plantation pictured here produces the tea known as Yubi-ch'a. Click

here for some more (rather romantic) photos of the Posong

tea fields, which have become a popular tourist spot.

of a more intensive kind, with the bushes

planted in neat rows and operated on an industrial scale, have

been established in various areas, the most important being

those found in Posong near Kangjin; other large industrial

tea-plantations can be found on the slopes of Wolch'ul-san, also

in the south-west, and and in the island of Cheju-do. The Posong

plantation pictured here produces the tea known as Yubi-ch'a. Click

here for some more (rather romantic) photos of the Posong

tea fields, which have become a popular tourist spot.

The remaining photos on this page were taken in Chiri Mountain

and show the making of Panyaro Tea by the great Tea Master Chae

Won-hwa.

Tea can only be made using the

fresh tips, the scarcely opened buds that start to grow in early

April. Once a leaf is fully developed, it is soon too

coarse for use. After late May the bushes may continue to

produce further shoots but these no longer have the intense

flavour needed for good tea. Therefore all the green tea needed

for the year has to be plucked and made in less than two months.

The very earliest buds have the finest flavour, and are the most

difficult to collect, especially if the winter frosts last late.

Tea can only be made using the

fresh tips, the scarcely opened buds that start to grow in early

April. Once a leaf is fully developed, it is soon too

coarse for use. After late May the bushes may continue to

produce further shoots but these no longer have the intense

flavour needed for good tea. Therefore all the green tea needed

for the year has to be plucked and made in less than two months.

The very earliest buds have the finest flavour, and are the most

difficult to collect, especially if the winter frosts last late.

The different

grades of green tea

The Korean calendar has twenty-four seasonal

dates based on the movement of the sun, which it borrowed from

Chinese tradition; the day known as Kok-u normally

falls on April 20. The tea gathered before this date is known as

Ujon and commands the highest price. The next

seasonal date Ipha falls on May 5-6, and tea

gathered between those two dates is known as Sejak.

Tea gathered after Ipha is known as Chungjak.

These names (also of Chinese origin) often figure on the menus

in tea-rooms, to the mystification of the uninformed public. It

should also be added that the Korean weather is colder than that

in China, with the result that Korean tea-makers, although they

pay lip-service to the traditional dates, actually go on making

'Ujon' from the first growth of shoots way beyond April 20, when

very often there are no new shoots on the tea bushes. The

earlier the tea, the more delicate the taste and the cooler the

water should be in making it, with many authorities recommending

that the water for Ujon should be cooled down to 50

degrees.

How green tea

is dried

The gathering of leaves

requires skill and speed. It is done mostly by the women of the

region, who can only collect a few pounds of leaves in the

course of a day. The drying of the leaves into tea for drinking

must be done within twenty-four hours of picking, before the

juices in them start to oxidize. In Korea as in Japan, the

easiest, industrialized method of drying green tea

involves the use of a revolving drum in which the leaves are

dried by a flow of hot air as the drum turns.

The gathering of leaves

requires skill and speed. It is done mostly by the women of the

region, who can only collect a few pounds of leaves in the

course of a day. The drying of the leaves into tea for drinking

must be done within twenty-four hours of picking, before the

juices in them start to oxidize. In Korea as in Japan, the

easiest, industrialized method of drying green tea

involves the use of a revolving drum in which the leaves are

dried by a flow of hot air as the drum turns.

There are two main methods of hand-drying in

use in Korea when making the best green tea. The way of drying

resulting in what is known as Puch'o-ch'a is much

more common; the fresh leaves are first tossed in a very hot

iron cauldron over a wood or (now more often) a gas fire, being

stirred constantly to prevent burning. This softens them. Then

the leaves are removed from the heat to be rubbed and rolled

vigorously on a flat surface, so that they curl tightly on

themselves. They are then returned to a less intense heat, and

the process is repeated a number of times, traditionally nine

times, until the leaves are completely dry.

With the tea known as Chung-ch'a,

represented by Panyaro tea, the fresh leaves are plunged for a

moment into nearly boiling water (left), then allowed to

drain for a couple of hours, before being placed over the fire.

Chung-ch'a is much commoner in Japan than in Korea

but after the initial stage there is little or no similarity in

the way of making the tea. The resulting teas are completely

different in color, taste and fragrance.

With Chung-ch'a the drying and rolling

are done concurrently, the leaves are not removed from the heat

until they are completely dried, after about two hours. During

this time, the leaves are constantly turned, rubbed, and pressed

to the bottom of the cauldron. The drying has to be completely

regular and at the same time no leaf must burn. An intense

fragrance emerges from the leaves as the drying advances.

This means that the people stirring and

rubbing the leaves between their (gloved) hands to roll them are

obliged to sit directly over the cauldron on its fire. Not

surprisingly, this tea, which has by far the finest fragrance,

is very expensive. It takes many years of experience to know

just when to stop the drying; tea which is removed from the fire

too quickly still contains moisture that can cause it to go

mildew after a few months.

(Pictures) Chae Won-hwa takes

charge of operations during the last 30 minutes or so. She

decides when the time has come to take the tea from the fire.

(Pictures) Chae Won-hwa takes

charge of operations during the last 30 minutes or so. She

decides when the time has come to take the tea from the fire.

She takes the tea into a

store-room which no one else is allowed to enter. She explains

that there she prays over the tea, and does whatever else is

needed to give her Panyaro tea its remarkable intensity of

flavour. She insists that when she has chosen someone to be her

authorized successor, she will instruct that person in these

final mysterious rites. It is important that the dried tea

leaves remain in a very warm, dry place until they are packed in

air-tight containers, so that the drying continues.

She takes the tea into a

store-room which no one else is allowed to enter. She explains

that there she prays over the tea, and does whatever else is

needed to give her Panyaro tea its remarkable intensity of

flavour. She insists that when she has chosen someone to be her

authorized successor, she will instruct that person in these

final mysterious rites. It is important that the dried tea

leaves remain in a very warm, dry place until they are packed in

air-tight containers, so that the drying continues.

The main difference between green tea

and the kinds known as oolong or red (in

English black) lies in the lack of oxidation,

also known inaccurately as fermentation. If the juices

and enzymes within the leaves are allowed to oxidize, their

surfaces having been bruised by initial cold rolling, and the

final drying delayed by several hours, the result will be an

immense variety of tastes quite unlike green tea.

Click to go on to the next

page or back to

the Index

Tea plantations

Tea plantations of a more intensive kind, with the bushes

planted in neat rows and operated on an industrial scale, have

been established in various areas, the most important being

those found in Posong near Kangjin; other large industrial

tea-plantations can be found on the slopes of Wolch'ul-san, also

in the south-west, and and in the island of Cheju-do. The Posong

plantation pictured here produces the tea known as Yubi-ch'a. Click

here for some more (rather romantic) photos of the Posong

tea fields, which have become a popular tourist spot.

of a more intensive kind, with the bushes

planted in neat rows and operated on an industrial scale, have

been established in various areas, the most important being

those found in Posong near Kangjin; other large industrial

tea-plantations can be found on the slopes of Wolch'ul-san, also

in the south-west, and and in the island of Cheju-do. The Posong

plantation pictured here produces the tea known as Yubi-ch'a. Click

here for some more (rather romantic) photos of the Posong

tea fields, which have become a popular tourist spot.