An Old Map and its Story

The Gonyeo-Manguk-Jeondo

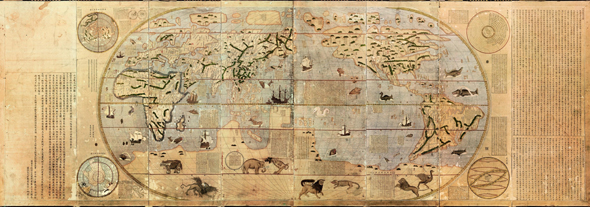

The map in question, known in Korean pronunciation as the Gonyeo-Manguk-Jeondo (곤여만국전도), was a Korean hand-copied reproduction made by Painter Kim Jin-yeo in 1708, the 34th year of King Sukjong's reign, of the Chinese Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (坤輿萬國全圖 Complete Map of the World). This map was printed in China at the request of the Wanli Emperor in 1602 by the Italian Catholic missionary Matteo Ricci and Chinese collaborators, Mandarin Zhong Wentao and the technical translator, Li Zhizao. It is the earliest known Chinese world map with the style of European maps.

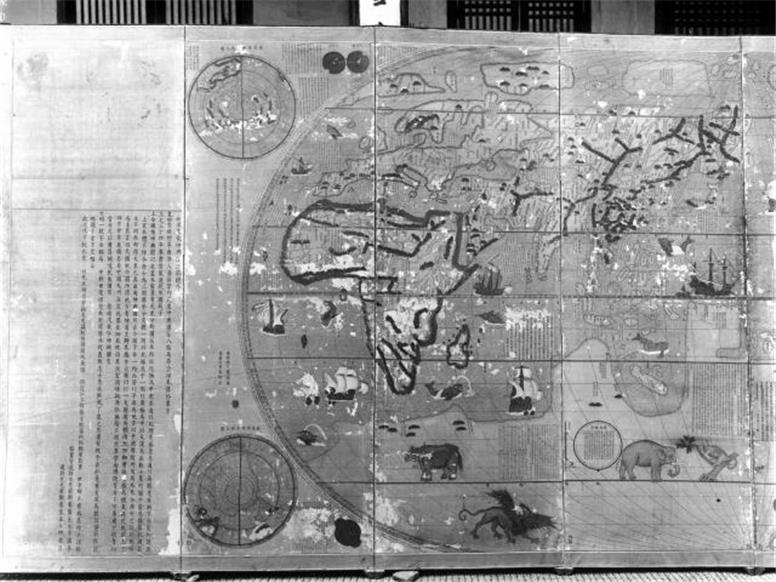

A copy of this map was brought to Korea by Lee Gwan-jeong and Gwon Hui, two envoys of Joseon to China and at least two copies were made. One is now displayed at Seoul National University Museum, and was designated National Treasure No.849 on August 9, 1985. The other known copy, that described by Bishop Trollope, was kept at Bongseonsa temple until it was destroyed when the temple buildings burned down during the Korean War, on March 6, 1951. Recently the Museum of Silhak in Namyangju City has created a virtual reconstruction of the Bongseonsa map, based on photographs taken in 1929 and by comparison with other copies in Japan and the United States. (This link gives access to an image which can be enlarged in order to see the details.)

The map was mounted on the seven leaves of a folding screen. The first panel contains texts by Ricci, the last a description of how the Korean copies were made. The central five panels show the five world continents and over 850 toponyms. The map contains descriptions of ethnic groups and the main products associated with each region. In the margins outside the ellipse, there are images of the northern and southern hemispheres, the Aristotelian geocentric world system, and the orbits of the sun and moon. It has an introduction by the then Prime Minister, Choe Seok-jeong providing information on the constitution of the map and its production process.

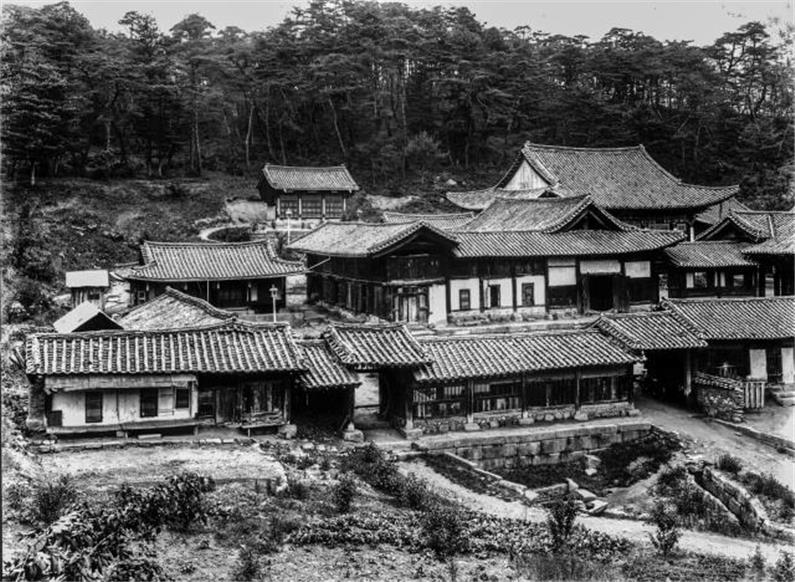

Bongseonsa temple was originally founded by National Preceptor Beobin in 969, with the name Unaksa, but after King Sejo (r. 1455–1468) was buried nearby, it was given a new name by Queen Jeonghui (aka Queen Dowager Jaseong, 1418 – 1483) who for many years acted as regent for her weak son, Yejong, and after his death for her grandson who became King Seongjong. The temple served as the funerary temple for Sejo and the continuing royal patronage of ensuing queens probably explains why the map was donated to it. The name can be interpreted as “temple for revering the sage.”

Korea as depicted in the Chinese original

Bongseonsa before the Korean War |

Part of the Bongseonsa Map photographed in 1929 |

The version of the map preserved in the Museum of SNU (보물 제 849)

An Old Map and its

Story

By Mark Napier Trollope,

Bishop in Korea.

I.

Some

twenty miles or more N. E. of Seoul, on the

beautifully wooded slopes of Bamboo-leaf Mountain 竹葉山 in the

prefecture of Yang-ju 楊州 lies Kwang-neung 光隨 the last

resting place of the great King Syei-jo 世祖大王, who reigned

over Chosen from A. D. 1455 to A. D. 1469. True it is

that the Neung, or royal mausolea, and the Buddhist

temples surrounded as they usually are by acres of

park or forest land have between them appropriated (or

helped to create) most of the beauty spots of Korea.

And certainly the Kwang Neung with its magnificent

park of giant trees of every sort, is one of the most

beautiful of the royal tombs which lie scattered so

thickly over the country in the neighbourhood of

Seoul. Probably for this reason it has been selected

by the “Woods and Forests Department” of the

Government-General as one of their “Auxiliary forestry

stations.”

King

Syei-jo was noted for two things. First, he was the

only king of the Yi dynasty who was an enthusiastic

devotee of Buddhism, and to him it was that Seoul owed

the erection within its walls of Won-gak-sa 圓覺寺, the great

Temple, of which the huge tablet and the beautiful

Pagoda of “Pagoda Park” are the only remaining relics.

His second claim to fame is a less enviable one. For

he, like our English King Richard III, is credited

with having played the part of the “wicked uncle,” who

turns up sooner or later in most dynastic histories,

paving his own way to the Throne by the murder of the

legitimate heir, his infant nephew. The boy King

Tan-jong 端宗大王, foully done to

death at the age of 16 in the mountain fastnesses of

Kang-won-do (A. D. 1457), is one of the most pathetic

characters in Korean history. And king Syei-jo’s

latter-day devotion to the Buddhist faith is said to

have been not unconnected with remorse for his share

in the tragedy which overshadowed his accession to the

throne.

And

so we find—as not unfrequently in the parks attached

to the royal tombs—a grave old Buddhist monastery 奉先寺 Pong-syen-sa,

embosomed in the woods surrounding Kwangneung, Syei-jo’s

tomb, founded presumably as a home for religious men

who should pray for the soul of the dead king. The

monastery, though its buildings are massive and fairly

extensive, is not in itself especially remarkable,

except for its great and glorious-toned bell, dating

from l469 and covered with Chinese inscriptions and

charms in the Sanskrit script. But the Poptang 法堂 or central

shrine, is a spacious and striking building, with its

heavy timbers,its elaborately

carved wood work and subdued colouring, and is further

note-worthy for the fact that, in the place of the

“gods many and lords many,” usually to be found (at

least to the number of three) over Buddhist altars, it

contains but a single figure of 藥師如來 Yak-sa-ye-rai,

the healing Buddha, or good physician, seated in grave

contemplation, with his casket of medicine in his

hands.

The

object of this paper however is not so much to draw

attention to King Syei-jo’s tomb or the temple of

Pong-syen-sa near by, as to that which must surely be

counted the Temple’s most precious possession, its

great Mappa

Mandi, the hand-work of one of those wonderful

Jesuit priests and scientists who flourished in Peking

in the seventeenth century. How this marvellous

creation found its way to Pong-syen-sa must remain

uncertain, the monks retaining no tradition on the

subject, though something of interest on the subject

remains to be said before this paper ends.

Every

Korean scholar of course is familiar with the name of

李瑪竇, Yi Ma-tou, and

with the great work he did in China towards the end of

the Ming Dynasty in teaching the truths of

mathematics, astronomy and geography, and amending the

many errors into which the Imperial Calendar had

fallen. But not all of them by any means are aware

that Yi Ma-tou is but the Chinese name adopted by

Father Matteo Ricci, who was born at Ancona in 1552

(the very year in which S. Francis Xavier died on the

coast of China), and who, after throwing in his lot

with S. Ignatius Loyola’s young and flourishing

Society of Jesus, found his way to the South of China

as a missionary priest in 1580, passing thence in 1600

to Peking, where he died full of years and honour in

1610.

Long

before Father Ricci died he had been joined in his

missionary labours by many other priests of the

Society of Jesus. And yet others flocked into the

Chinese Empire after his death, carrying on the

tradition which he established for close on two

centuries, until in 1773 the suppression of the

Society by the Pope brought disaster to its

flourishing Chinese Missions as well as its work

elsewhere [*The Society of Jesus was revived

in 1814 by Pope Pius VII just forty-one years after it

had been suppressed by his predecessor, pope Clement XIV

in 1773. Their great establishment at Sicawei near

Shanghai dates from their re-entry on Chinese Mission

work in 1842.]

Among Fr. Ricci’s Jesuit successors in Peking, far the

most famous were Fr. John Adam Schall, a native of

Cologne, who arrived in China in 1622 and died there

in 1655, and Fr. Ferdinand Verbiest, a native of

Flanders, who arrived in China in 1660 and died there

in 1688. The former is known to Chinese and Koreans as

湯若望 Tang Yak-mang,

and the latter as 南懷仁, Nam Hoiin. Both were men of

extraordinary scientific attainments and were held in

the highest esteem in Peking, where they were actually

raised to mandarin rank and successively appointed

President of the Board of Mathematics and Astronomy by

the last Emperors of the Ming and the earliest

Emperors of the Ching, or Manchu, dynasty.

It

is to Fr. Adam Schall, Tang Yak-mang (pronounced in

Chinese Tang Jo-wang), that we owe the great map of

the world still preserved in Pong-syen-sa. My own

inspection of the map was too cursory, and the space

of THE KOREA MAGAZINE too valuable,

for me to attempt a minute description of this work of

art in these columns. Suffice it to say that it is

painted in colours on silk, with the geographical

names and other details written in Chinese, and that

the whole is mounted on an eight-leaved screen some

six or seven feet high.

The

first leaf contains a long extract in Chinese from the

writings of Yi Ma-tou (Matthew Ricci), and the eighth

an historical account of the way in which the map came

into being. The map is there said to have been drawn

in the 1st Year of the Emperor 崇禎 i.e. A. D. 1628

by the 西洋人湯若望 the “western

foreigner Tang Yak-mang, who affixed his seal to it

and sent it to the eastern kingdom,” i.e. Chosen. It

is further stated that in the 34th year of King

Souk-jong 肅宗 of Chosen (i.e.

A. D. 1708) several copies of the Map were made by

royal authority. And the whole of this statement is

signed by 崔錫鼎 Choi

Syek-tyeng, who was (Dr. Gale informs me) Prime

Minister of Korea at the last mentioned date. The six

central leaves of the screen are occupied with the map

of the world itself, surrounded by other drawings

illustrating the principle of eclipses, the orbits of

the planets, etc., and at the side is to be seen in

red ink, the sacred monogram I. H. S. and the Jesuit

emblem of the Cross and three nails. The map itself is

drawn with the Equator, the Tropics and the North and

South Poles clearly marked, and plainly represents the

highest level of geographical accuracy attained by

European scientists in the first half of the

Seventeenth Century. The great continents of Europe,

Asia, Africa, and North and South America are

delineated with remarkable accuracy of outline, the

least satisfactory part being that great District of

Eastern Europe and Western Asia, which is now covered

by Russia and about which, one may suppose, but little

was really known in Europe at this time. Naturally

Australia is practically non-existent and the southern

parts of the globe generally are plainly those about

which our map-makers were most hazy. They have filled

the vacant spaces here with lively representation of

the Elephant, the Rhinoceros, the Lion and other

strange wild beasts, and after the manner of the

seventeenth century geographers, have dotted over the

vast surface of the ocean wonderful pictures of

dolphins and whales and gallant ships employed in the

commerce of the world. Useful and interesting pieces

of information are conveyed by little Chinese

inscriptions attached to the names of certain of the

countries, as for instance to Judaea, of which we are

told that “it is called the Holy Land because the Son

of God was born there,’’ while attention is drawn to

Rome as the residence of the Pope, and England is

described as the land in which no poisonous snakes are

to be found. (An early instance this of English

perfidy in appropriating to herself what really

belongs to Ireland!)

II

Now,

how did this map ever find its way to Chosen, the

hermit land? As I have already said, the monks of

Pong-syen-sa have no tradition on the subject and the

records of their monastery seem to have (as is alas!

so often the case) entirely disappeared. They

themselves had nothing to suggest, but that it must

have been brought back by one of the tribute Embassies

from Peking, which is likely enough. Can we get any

nearer to the truth? I think we can. It must be

remembered that the years during which Adam Schall

played such a prominent part in Peking (1622-1665)

were precisely the years during which the Chinese

Empire was passing from the hands of the Ming dynasty

to those of the rising Manchu power. Even before this

great crisis however, in the year 1631, we read in the

dynastic history of Chosen 國朝寶鑑 국됴보같 (as Dr. Gale

has pointed out to me) that the Korean envoy 鄭斗源 had met a

foreigner in Peking named 陸若漢 (probably

Father Jean de la Roque) who had much impressed him by

his hale and hearty old age (he was then 97 years old)

and who had presented him with number of guns,

telescopes, clocks and other articles’ of European

manufacture. This however does not yet bring into

direct contact with Adam Schall. And it is a little

bit difficult to piece together the events of the next

few years because they are all mixed up with the

events of the 丙

子胡亂

i.e. the Manchu invasion of Korea in 1636-7, which the

Koreans have always regarded as one of the most

shameful episodes in their history, and to which

therefore but scant reference is made in the dynastic

records. Practically all we are told there is that the

King of Korea moved his court from Seoul to Nam Han in

l636 and returned to Seoul in 1637, and that in 1644

an envoy 金 堉 was sent from

Seoul to Peking, where he is said to have met the

foreigner Adam Schall, 湯若 望 (A piece of information for which I have

again to thank Dr. Gale). What really took place was

this. The Manchu Emperor at the head of his army swept

down into Korea in 1636, to enforce the submission of

the Koreans, who clung to the falling Ming dynasty,

with a loyalty worthy of the Jacobites of Great

Britain in 1715 and 1745. The king had just time to

send off his two eldest sons (together with his

ancestral tablets) and members of his family to

Kang-wha, where they were shortly afterwards captured,

while he himself had to flee with the rest of his

court to Nam Han San Song, some twenty miles south of

Seoul where he sustained a long siege. At length being

starved out he surrendered to the Manchu Emperor, who

treated him with surprising courtesy and clemency.

Among the conditions of peace however he insisted on

carrying off to Moukden as hostages the Crown Prince

of Korea, and his younger brother the Prince Pong-nim,

who remained there in a sort of gilded captivity until

1645, when they were allowed to return to Korea, the

last of the Ming Emperors having died by his own hand

in 1644, and thus cleared the road for the Manchu

Emperor’s peaceful accession to the throne of China.

It was probably in connection with these events in

1644-5 that 金堉 went as an

envoy to China, where, as we have already said, he is

recorded to have met Father Schall 湯若望. And even if we

had nothing else to go upon, we should probably not be

far wrong in concluding that this was the occasion on

which Father Schall’s Mappa Mandi

found its way from China to Chosen.

In

pursuing my investigation however as to Father

Schall’s activities, in Peking, I happened to refer to

that well-known traveller the Abbe Huc’s book on “Le

Christianism en Chine, en Tartarie et au Thibet,”

which was published in 1857. And there I stumbled upon

a narrative which shewed that Father Schall had in

l644-5 entered into the most friendly relations with a

far more distinguished person than any mere envoy like

(金堉) to wit with no

less a person than the captive Korean Prince, who

afterwards mounted his father’s throne as King

Hyo-jong (孝 宗大王) and reigned in

Chosen from A. D. 1649-1669.

The

facts recorded by the Abbe Hue are of such surpassing

interest that it seems worthwhile to insert the

passage here at length, especially as none of the many

writers in Korea seem to have noticed them [†Griffis

in Korea, the

Hermit Nation, Hulbert in his Passing of Korea

and History of

Korea, Dallet in the Histoire de

l’Eglyre de Coree, Longford in his Story of Korea

make no mention of the episode in question, though they

all refer to instances of Korean envoys meeting some of

the Jesuit Fathers in China. Ross in his History of Corea,

Ancient and Modern has an oblique reference to the

meeting of the Crown Prince and Father Schall, quoting

from the Edinburgh

Review, No. 278. but only mentions it to scout its

probability.]

I ought however to say by way of preface that the Abbé

is wrong in referring to the “illustrious captive” as

being then “King of the Koreans.” It was the Crown

Prince and his younger brother Prince Pong Nim who

were carried off to China as hostages. Of these the

Crown Prince himself died in 1645, almost immediately

after his return to his native land; and it was his

younger brother, Prince Pong Nim, who afterwards

actually became King of Korea and reigned as Hyo-jong

Tai-wang from 1649 to 1659.

Referring

to the years 1644-5, when the last of the Ming

Emperors had passed away and the Manchu Emperor

Syoun-chi 順治(순치) had at length

mounted the throne of China, the Abbe Hue says:

“At

about this date the King of the Koreans was in Peking.

Having fallen into the hands of the Manchus as a

prisoner of war, he had been taken to Moukden, the

capital of Manchuria, where the Tartar chief had

promised to set him free as soon as he had made

himself master of the Chinese Empire. No sooner had

Syoun-chi been proclaimed Emperor than he fulfilled

the promise made to his illustrious captive, who

before returning to his native land expressed a desire

to visit Peking and return thanks in person to his

liberator. And it was during his stay there that the

King of Korea (i.e. the Crown Prince) made the

acquaintance of Father Adam Schall. He used to take

the greatest pleasure in visiting the Jesuit Father

informally at his residence and himself entertained

him with the greatest kindness in his own palace. He

was particularly anxious that the distinguished

Koreans who were attached to his suite should profit

by the instructive conversation which took place on

these occasions, and trusted that they might gather

therefrom, and carry back to their own country,

valuable information on matters astronomical and

mathematical, in which his countrymen were not very

well skilled. The missionary on his side did not fail

to take the opportunity thus provided of instilling

the truths of Christianity into the minds of his new

friends, in the hope that the seeds of the true faith

might thus be sown in the as yet heathen land of

Korea. Little by little they became attached to one

another by ties of the closest intimacy, and the

inevitable parting, when the Prince and his suite took

their departure for Korea, brought with it a pang of

real regret to both parties. As the Korean Prince took

a great interest in Chinese literature, Fr. Schall

sent him, a few days before his departure from Peking,

copies of all the works on science and religion

composed by the Jesuit Fathers, together with a

celestial globe and a beautiful image of our Saviour.

The prince was so charmed with these gifts that he

wrote personally to Father Schall a letter in Chinese

to express his heartfelt gratitude. Subjoined is the

translation of this precious document:

“‘Yesterday,’

said the prince to Father Schall, ‘while examining the

wholly unexpected gift which you have sent me—the

image of the Divine Saviour, the celestial globe, the

astronomical works, and the numerous other books on

the sciences and doctrine of Europe—I was so overcome

with joy that I am afraid I failed to give proper

expression to my gratitude. In looking through some of

these valuable works, I have observed that they

contain doctrines well calculated to perfect man’s

heart and to adorn it with all the virtues. Up to the

present, this sublime teaching has been unknown in our

country, where men’s understandings have been involved

in the grossest obscurity. The sacred image which you

have sent me is remarkably impressive. So much so that

when it is hung on the wall, one has but to look at it

to feel one’s soul at peace and cleansed from every

sort of stain. The globe and the books on astronomy

are works of such indispensable importance in any

State, that I can hardly credit my good fortune in

having become possessed of them. Similar works are

doubtless to be found in my country, but I must

sorrowfully admit that they are full of errors and in

process of time have drifted further and further away

from standards of scientific accuracy. You will

readily understand how happy your generous present bas

made me. As soon as I have returned to my native land,

these works shall be placed in an honourable position

in my palace and I propose to have reprints made for

distribution among those who by their studious habits

and devotion to science are most likely to profit by

them. By this means my subjects will in the near

future be able to appreciate the good fortune which

had enabled them to pass from the wilderness of

ignorance into the temple of erudition. And the

Koreans will not fail to recognize that it is to the

learned men of Europe that these benifits are due. How

strange it is that you and I, sprung from different

kingdoms and from countries so far apart and so widely

separated by the waters of the ocean, should have met

here in a strange land and that we should have formed

such an intimate friendship that we might be supposed

to be united by a “blood-contract.” It beats my

comprehension to understand by what occult power of

nature this has been brought about. And I can only

surmise that the souls of men are drawn to one another

by their devotion to Truth, however widely separated

they may be from one another on the Earth’s surface.

As it is I can but congratulate myself on my good

fortune in being able to carry back home these books

and this sacred image. When however I remember that my

subjects have never heard of the worship due to God,

and that they are likely enough to offend the Divine

Majesty by failure to show Him the proper respect my

heart is filled with disquiet and anxiety. And for

this reason I have thought it best, if you will allow

me to do so, to return you the sacred image, for I

should be very much to blame, if I or my people failed

to treat it with due veneration

“If

I can find anything worthy of your acceptance in my

native land, I shall ask your acceptance of it as a

token of my gratitude. That will be but a slight

return for the ten thousand favours which you have

showered on me.’”

The

good Abbe goes on to say that the young prince’s

expressed desire to return the sacred image

(presumably a Crucifix) was only due to his wish to

conform lo the accepted standards of Chinese

politeness, and that Fr. Schall not only prevailed on

him to keep it, but asked whether he would not like to

take back one of his catechists to preach the religion

of the true God to the Koreans. The prince replied

that he should much prefer to take back one of the

European fathers with him, but that anyone whom Fr.

Schall sent might count on receiving as warm a

reception as would be accorded to the missionary

himself. But, as the Abbe Hue points out, the dearth

of workers in the Chinese mission made it impossible

to carry out Fr. Schall’s scheme for starting

Christian mission work in Korea.

I

am endeavouring to find out whether the original of

the Korean prince’s letter is still preserved among

the archives of the Jesuit Missions in China. But even

in the absence of the original, and after making all

allowances for exaggerations possibly due to the Abbe

Hue’s editorial imagination, the letter bears on its

face the marks of truth and not improbably shews how

the Mappa Mandi

now in Pong-syen sa reached Korea. The prince’s

embarrassment about the Crucifix and his desire to get

rid of that, without hurting the donor’s feelings, and

at the same to retain the books, etc., is a very

characteristic touch.

And the whole

picture is rather a charming one. There is on the one

hand the young prince, who cannot have been more than

twenty-five years old. (And we all know how delightful

well-born and well-bred young Koreans of twenty-five

summers can be). Then there is the old German Jesuit,

one of the most brilliant scientists of his time, who

must have been about fifty-five years old at the time

of his meeting with the Korean prince. The old man

seems to have been of a singularly affectionate

disposition, fond of the society of young men, and

capable of eliciting from them the warmest feelings of

friendship. The affectionate tone of the Korean

prince’s letter is all of a piece with the terms of

extraordinarily warm hearted intimacy on which the

young Manchu Emperor Syoun-chi lived with his dear old

“Mafia” (the Manchu word for “daddy”), as he called

Fr. Adam Schall, The Abbe Huc has many an amusing tale

to tell of the embarrassment caused by the Emperor’s

frequent and very informal calls on the good Jesuit

Fathers in Peking. [†The Emperor was only a

child of six years old when he ascended the throne in

1644 and barely twenty-four when he died in 1661.] And it is

interesting to think that in the great Map of the

World preserved in Pong Syen-sa we in Korea have so

solid a link with such an interesting episode, or

series of episodes, in the past history of the Far

East and its relations with the West.

For Reference

Wikipedia

article on the original map

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunyu_Wanguo_Quantu

The Google page

with the reconstructed map from Bongsonsa and a

description. The map can be enlarged to make the texts

legible.

https://g.co/arts/jJc99R2V9KLRWKDaA

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/twGEi2Om9Nmouw

A series of

photos including the 1929 photos of the Map and of the

temple before its destruction

http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0023921#modal

A short history

of the temple in Korean

http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0023921

A brief English

Wikipedia entry for the temple

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bongseonsa