Carles in 1889

|

Helen Maude Carles in

1898

|

William

Richard Carles and Korea

W. R. Carles’s book Life in Corea, published in 1888, is one of the

very first books about the country based entirely on personal

experience. Carles made 2 visits to Korea from China, where he

was working in the British Consular Service. The first was a

private visit made in later 1883, then he was appointed

Vice-Consul in Korea in April 1884 and served there until some

time in 1885. Later in 1884, he was charged with making an

exploration of the economic potential of the northern regions,

which were still unexplored by any western power. This journey

lasted from September 29 until November 7, 1884. He then left

for a visit to China, and was absent during the aborted Gapsin

coup of December. He describes both journeys in his book.

Click here for a

PDF file of the Blue Book Report by

Mr. Carles on a Journey in two of the Central Provinces of

Corea, in October 1883. (published 1884)

Click here for a PDF file of the Blue Book Report by Vice-Consul Carles of a Journey from

Söul to the Phyöng Kang gold-washings, Dated May 12, 1885.

(published 1885)

Click here for a PDF file of the text of his

White Paper Report of a

Journey by Mr. Carles in the North of Corea

presented to Parliament and published in 1885

Click here for a PDF file of the text of

his paper presented to the Royal Geographical Society in

London early in 1886 and published in their journal

that year

Click here for a PDF file of a corrected scan of his book Life in Corea (published 1888, reprinted in 1894)

No account of Carles's life seems ever to have been published.

What follows is mostly based on records and materials available

through the Internet.

The Life of William Richard Carles

by Brother Anthony

William Richard Carles

(1848 – 1929) was the second son of the Rev. Charles Edward

Carles, B.A., Vicar of the parish of

Haselor, Warwick, and Georgiana Baker, his wife. His father had

studied at Catherine Hall, Cambridge. His elder brother, Charles

Wyndham Carles (1842-1914. M.A. Lincoln College, Oxon) was born

on 29th December, 1842. William Richard Carles was born in

Warwick on June 1, 1848. Both brothers were educated at

Marlborough College, where they played cricket. William Richard

entered the Consular Service in 1867, when he was sent as a

student interpreter to China, nominated by Marlborough School.

He served in various parts of China from 1867 to 1901. Among the

posts he held was that of Assistant Chinese Secretary, a

testimony to his language ability (Coates, p.139). He reports in

Life in Corea

that his first journey in Korea was a private one made in the

early winter of 1883, at the time that a treaty between Great

Britain and Korea was being negotiated by Sir Harry Parkes. He

was appointed “provisionally” British Vice-Consul for Corea on

March 17, 1884, at the same time as William George Aston (1841-1911), then Consul at Nagasaki, was appointed to be “provisionally” Her Majesty's Consul-General

(The London Gazette,

March 25, 1884, p. 1404). Both served there in 1884 and into

1885 and were the first European representatives to reside for

any length of time in Korea. Carles was perhaps chosen for the

position on account of his knowledge of Chinese.

Aston was born in Londonderry, educated at Queen’s College, Belfast, and had been in Japan since 1864, arriving there first as a student interpreter. He had been studying Korean since the mid-1870s and was very fluent in both Japanese and Korean. He had accompanied Vice-Admiral Willes in 1882 as interpreter during his visit to Korea, when Willes drew up a treaty based on the American treaty with Korea, and signed it on behalf of the British government, but this treaty was later repudiated by the British government. Aston, with others, had to make repeated visits to Korea in 1883 to negotiate a new treaty, which Aston and Sir Harry Parkes, the British Minister to China, drafted. This new treaty, the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce between Her Majesty [Queen Victoria] and His Majesty the King of Korea, was signed at Seoul on 26 November 1883, and marks the beginning of Anglo-Korean relations. It was Aston who in May 1884 secured the land on which the British legation / embassy now stands.

Carles says in his Life in Corea that in

all he spent some 18 months in the country. The first part of

the book, chapters 1-4, describe his first visit late in 1883.

This was a private visit, on the invitation of a Mr. Paterson, a

partner in the firm of Messrs Jardine, Matheson & Co.. It

happened to coincide with the visit by Sir Harry Parkes to Korea

to negociate the new treaty. Carles accompanied two other

Englishmen, Paterson and Morrison, and a Dane, the rest of the

group being composed of Chinese servants, 3 ponies and several

dogs. They arrived at Chemulpo from Shanghai on November 9,

1883. After a few days in “Soul” (the way Carles always spells

Seoul), on November 16 they set out to explore the mining areas

immediately to the north and east in already freezing weather.

After returning they spent a few more days in Seoul, then they

went to Chemulpo to return to Shanghai but their boat had left.

They were obliged to take another boat to Busan, then on to

Shanghai, where they arrived on Christmas Eve, 1883.

After being appointed

Vice-Consul in April 1884, Carles returned to Korea at the end

of April and attended the ceremony in the palace on May 1, 1884,

when Sir Harry Parkes presented a letter from Queen Victoria to

the King. After the conclusion of the ceremonies, Carles took up

residence as Vice-Consul in Chemulpo, which was still a very

small settlement with no adequate buildings and little to do. He

made occasional visits to Seoul, endured a dreadful summer, then

early in September he was ordered by London to make a survey of

the so-far unexplored northern regions, to see if there were

business prospects for Britain in that direction. They set off

on September 27 and returned to Seoul on November 8. On his

return, Carles was ordered to take up the position of

Vice-Consul in “Fusan” (as it was then known). He therefore sent

his furniture down to Fusan and left for a short visit to

Shanghai. He had not returned when the Gapsin Coup erupted on

December 4.

On December 4, 1884, Aston attended the dinner held to celebrate the opening of the Korean Post Office, during which a group of pro-Japanese reformists staged the Gapsin coup, killing and wounding many of the pro-Chinese conservative ministers. Aston and his colleagues were taken through icy streets to the safety of the American legation. A few days later, on December 9, Aston wrote informing the Korean foreign Minister that he had decided to move the Consulate-General to Chemulpo, presumably to the building that Carles had recently vacated. Aston fell sick at this moment and was obliged to leave Korea to convalesce in Japan, late in December or early in January. Carles had clearly returned to Korea quickly and on January 12 wrote from Chemulpo as "acting Consul-General" to inform the Korean foreign Minister that Aston had left the country.

Carles was present at and

describes in his book Life in

Corea events in Seoul during the spring of 1885, and

lists the gifts of food he received from the King. He does not

say when he left Korea.The last communication from Carles

appears to be on 5 May, in which he notes the appointment of E.

H. Parker to be second Vice Consul in Korea, to be based

at Pusan. (Korea University, p. 126) By 12 June 1885, Aston was

clearly back in Korea, for on that day he wrote to the Foreign

Ministry about the possible grant of border trade rights to

Russia. (p. 137) Aston‘s last communication was on 22 October

1885, when he wrote to the Foreign Minister saying that he had

that day handed over charge of Consulate General to E. Colbourne

Baber, “who will discharge the duties of Her Majesty’s Consul

General during my absence on home leave.” (.p.177) He

seems not to have returned to Asia after that.

We know

that Carles was in London in January 1886, when he presented his

paper about Korea to the Royal Geographical Society. In July

1886, Carles was appointed Vice-Consul at Shanghai (The London Gazette, July

13, 1886, p. 3396). He cannot have left at once, though, since

he and Helen Maude James were married in Devon in September

1886. He was appointed Consul at Chinkiang (Zhenjiang) in July,

1889 (The London Gazette,

July 19, 1889, p. 3895). His wife, Helen Maude, is recorded as

having given birth

to a son at Shanghai in 1890 (North China Herald,

February 14, 1890, page 1.) but the newspaper records no name

and nothing more is known of him. Another son, Alan James, was

born on 1 February, 1894, in Chinkiang.

In September, 1897, Carles

was appointed Consul at Swatow (The London Gazette, November 15, 1897, p. 6077).

In May, 1899, he was made Consul at Tientsin / Tianjin (The London Gazette,

June 20, 1899, p. 8866) and was promoted to Consul-General there

in June, 1900 (The London

Gazette, August 14, 1900, p. 5032). During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, he

attempted to act as go-between for the besieged legation in

Peking. Carles apparently came in for criticism at the

time of the Boxer uprising. He sent a message which

Lancelot Giles, one of the student interpreters at the Legation

in Beijing said caused “much comment and ridicule”. The

message read: “Yours of July 4. 24 troops have now landed, and

19,000 here. Gen.Gasalee expected Taku tomorrow. Russians hold

Pei Tsang. Tientsin under foreign government; and Boxer power

exploded here. Plenty of troops on the way, if you can hold out

with food. Almost all ladies have left Tientsin.” Giles said

that he thought the message perfectly clear and “probably

purposely obscured to avoid giving the Chinese any news, if it

fell into their hands.” (Lancelot Giles, The Siege of the Peking Legations:

A Diary, ed. With introduction by L. G. Marchant,

University of Western Australia Press, 1970, pp. 165-66,

entry for 28 July 1900.)

Tianjin was the scene of

heavy fighting during the Boxer uprising and endured a long

siege. In

January, 1901, Carles was made a Companion of the Order of Saint

Michael and Saint George and he seems to have retired back to

England soon after. Coates writes that Carles “…collapsed from

overwork and anxiety less than a month after the legations had

been relieved, went home sick, and retired. The Foreign Office

showed their opinion of criticism of his behaviour in Tientsin

by procuring for him a CMG. (p. 187) Apparently, he “… collapsed

so completely at Tientsin under the Boxer strain that

absolute cessation of work was medically ordered.” (p. 357).

Carles was one of six successive consuls at Tientsin who had

some form of nervous breakdown (p.357). After his return

to England, apart from a paper on the history of Shanghai he

presented to the China Society in London in May 1916, there is

no record of any activity by him for the rest of his life.

During the time he spent

in Korea, Carles made several trips to explore the interior of

the country. He published reports about them in various places,

including at least one Government Paper, the paper given to and

published by the Geographical Society of London in 1886, and in

The Field, before

publishing his Life in

Corea in 1888. The book was republished in 1894. Apart

from the monumental Choson:

The Land of the Morning Calm by the American Perceval

Lowell dated 1886, it is the first book-length account of Korea

published on the basis of an extended period of residence in the

country. William Elliot Griffis had published his Corea, The Hermit Nation

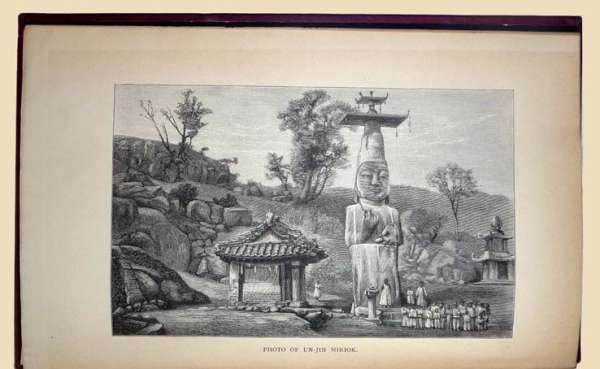

in 1882 without once setting foot in the country. Carles’ book

includes photos taken by Lieut. G. C. Foulk U.S.N., “who was in

charge of the united States Legation in Soul while I was there

in the early part of 1885.” Foulk made a heroic journey through

the southern regions of Korea in the autumn of 1884, but his

account of it was not published until 2008.

Carles was a keen botanist

and he sent plants which he collected to the Royal Botanic

Garden in England. In addition to Korea, he collected plants and

sent them back to Britain from China (1877-98: Fukien; Hopeh;

Kiangsu); India (1884-91 ); and Japan (1892-96). His name was

given (unbeknown to himself) to the wonderfully fragrant Korean

Spicebush Viburnum (Viburnum

carlesii) by William Botting Hemsley, Director of Kew

Gardens. He became a Fellow of the Linnaean Society of London in

1898. A set of his plants from Korea, Kiangsu, and Fokien is in

the Kew Herbarium. He also indicates in his book that he was a

keen hunter and always hoped to do some shooting, killing both

birds and animals, like so many others of his time.

William Richard Carles and

his wife Helen Maude were residing at “Silwood”, The Park,

Cheltenham (Gloucester) at the 1911 Census, together with Helen

Mary, a daughter aged 23, born in China, and 3 sons, Richard

Eric (aged 18, born in Berkshire), John Robin (aged 11, born in

China) and Henley William (aged 8, born in Dorset). Their son

Alan James (aged 17, born in 1894 in China) was serving as a

naval cadet at the time. Mrs. Carles’s brother, John Ernest

James, a retired school-master, was living with them, as were

four servants and a “hospital nurse.” Charles Wyndham Carles,

William Richard’s older brother, also a retired school-master,

is recorded as being present as a visitor in a nearby house

(“The Woodlands” The Park, Cheltenham) on the day of the census.

Perhaps he had come on a visit and there was no room for him in

his brother’s house? He was headmaster of Cothill School,

Marcham, Berkshire at the time of the 1891 census. The census

report records Mrs. Carles's age as 51, which would mean she was

born in 1860. She was 11-12 years younger than her husband,

A few years later, during

the war, Lt Alan James Carles, Royal Navy, was killed (missing

in action) when HM Submarine E22 was sunk on 25th April 1916, in

the North Sea off Harwich. Acting Captain Richard Eric Carles of

the Bedforshire Regiment was awarded the Military Medal “for

conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty” (Supplement to The London

Gazette, 22 June, 1918), the location is not specified. He

died on 14 December 1924, aged only 32.

William Richard Carles

died in June, 1929, in Bradfield, Berkshire. His wife lived on

until 26 November, 1953, when she died in Reading, Berkshire.

Publications

Corea. No. 2 (1885). Report Of a Journey

by Mr Carles in The North of Corea. Presented to both Houses

of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. April 1885.

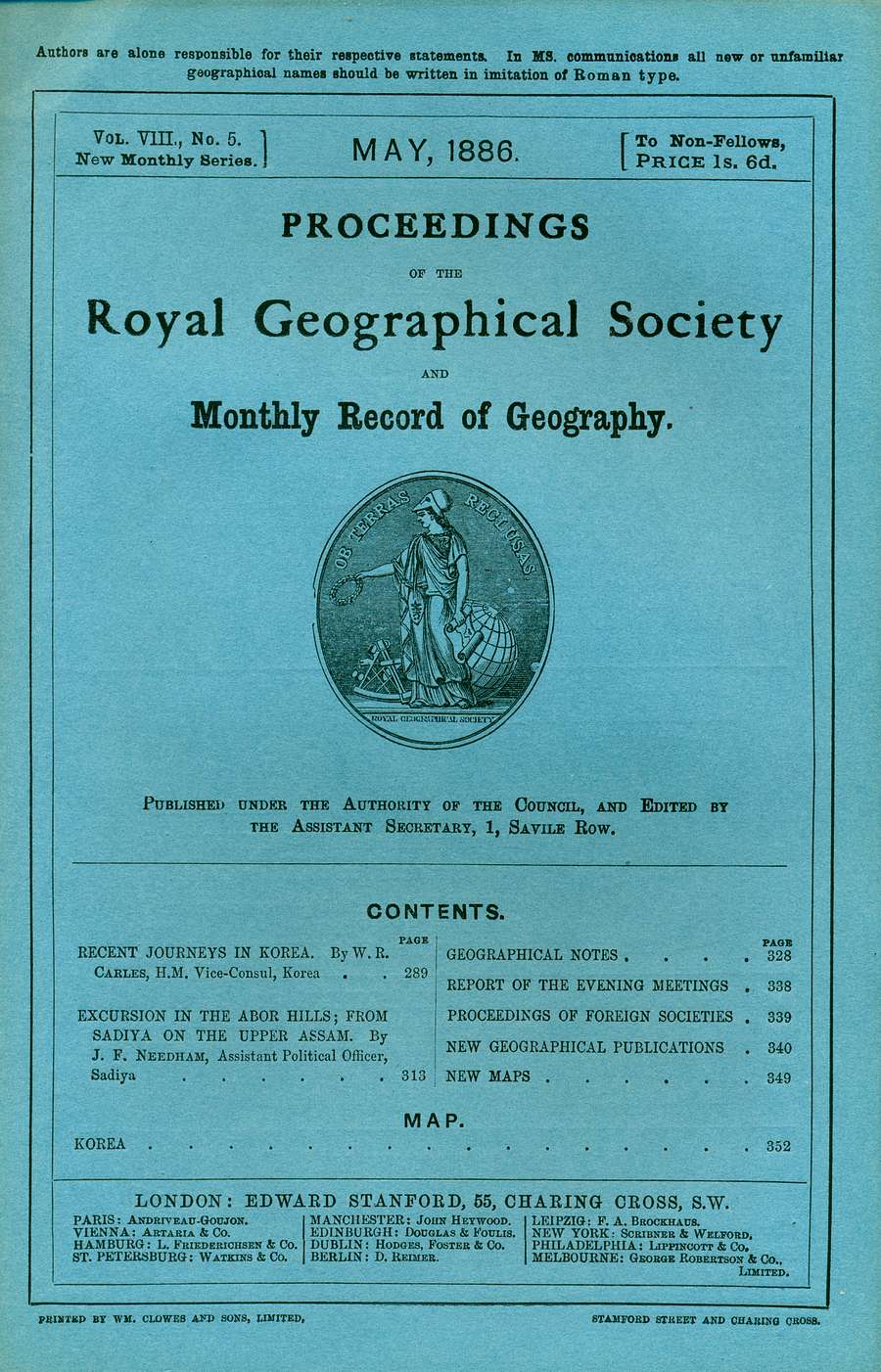

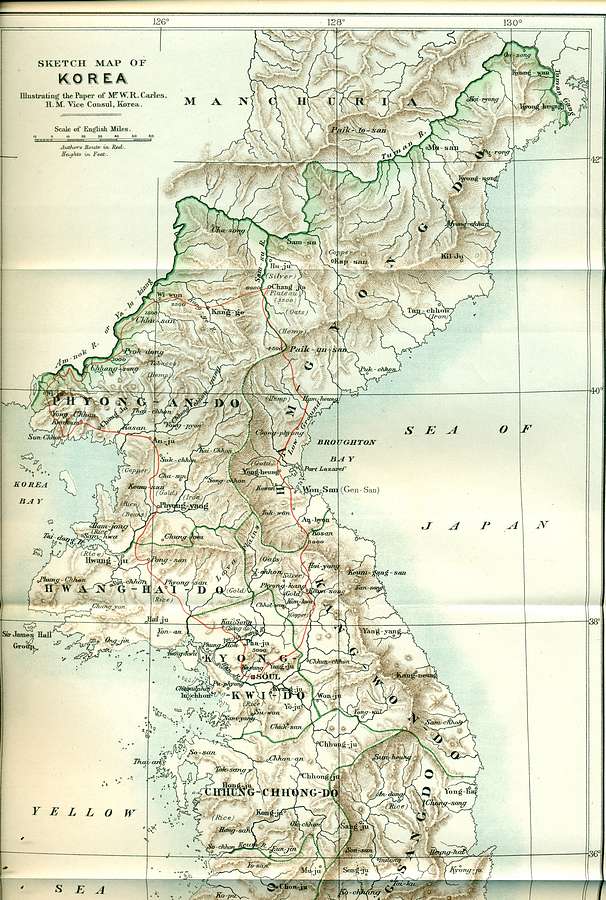

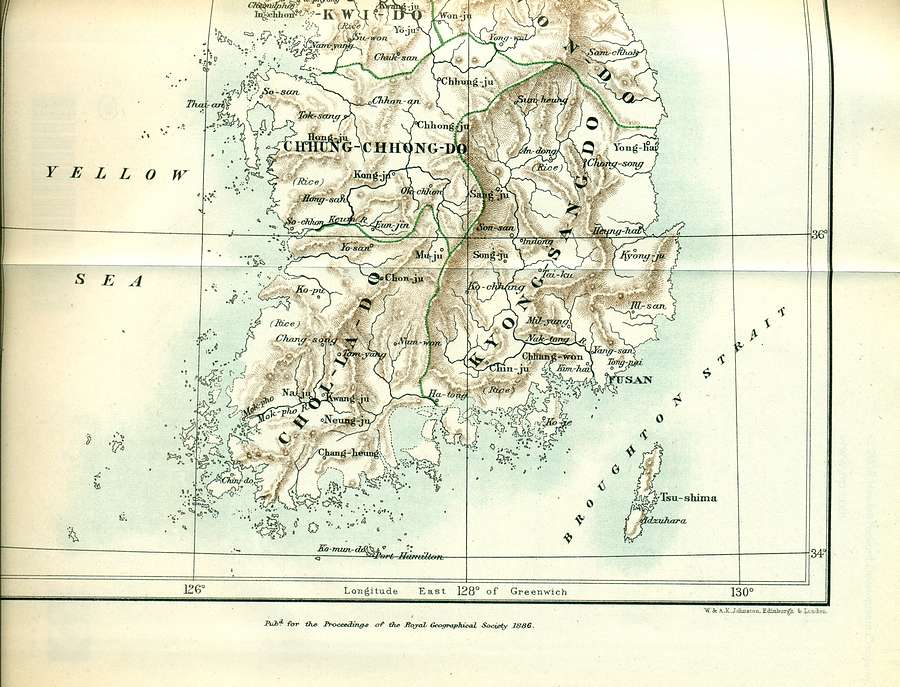

“Recent Journeys in

Korea.” In The

Proceedings of The Royal Geographical Society and Monthly

Record of Geography Vol. VIII, No. 5. May, 1886. pages 289

– 312, having been read at the Evening Meeting of the Society,

January 25th, 1886.

Life in Corea (London ; New York :

Macmillan and Co. 1888, 1894)

Online at: http://archive.org/details/cu31924023275641

"The Yangtse Chiang", The Geographical Journal,

Vol. 12, No. 3 (Sep., 1898), pp. 225–240; Published by:

Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society

(with the Institute of British Geographers)

Some Pages in the History of Shanghai, 1842-1856 : A Paper Read

Before the China Society on May 23, 1916. (London : East & West,

Ltd. 1916)

Online at:

http://archive.org/details/cu31924023217809

“The Emperor Kang Hsi's Edict on Mountains and Rivers of China. A translation of the edict originally published in the winter of 1720-21.” 12pp. Map. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. 1922.

Sources

Some of the detailed

information in the text above is supplied by the first volume of

Korea diplomatic documents relating to Britain published by

Korea University in 1968 (quoted in correspondence by J. E.

Hoare).

P. D. Coates, The China

Consuls , Hong Kong; Oxford University Press,

1988,

See also Peter

Korniki’s online account of Aston’s life and activities: