10

Rome and the Roman Empire

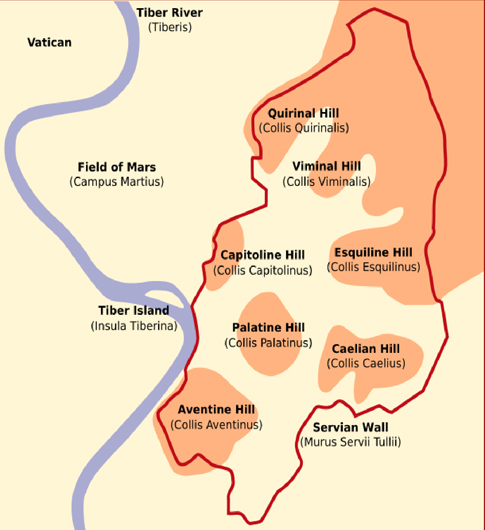

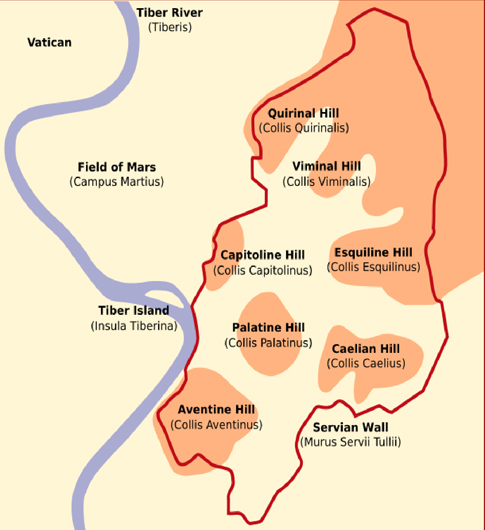

Seven hills of Rome

|

|

The legendary story of

the founding of Rome by the twins Romulus and Remus

is a strange Founding Myth. According to its account, Remus

mocked Romulus' work by jumping over the scarcely-begun walls;

Romulus then killed his brother and founded Rome alone, giving

it his own name. The twins, said to have been suckled by a wolf

as babies, were later described as descendants of Aeneas from

Troy. That reflects a desire to connect Rome with the splendours

of ancient Greek tradition and mythology. The traditional date for the founding

of Rome was 753 B.C. Archeology shows that by 575, if

not earlier, small villages on the site of Rome were beginning

to coalesce into a larger city-state (in Latin urbs,) with

advances in civilized living being made under Etruscan

influence. The

first temple, of Jupiter on the Capitol, was built at this time.

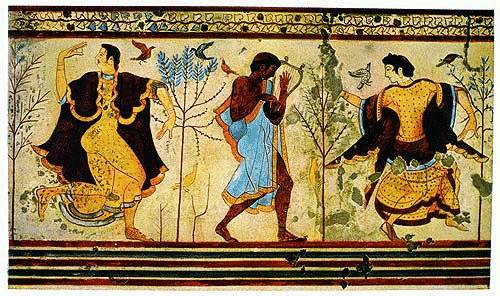

The Etruscans, whose

still-undeciphered language was

not of Indo-European origin, lived in areas near Rome and

their artistic culture has left some remarkable clay statues of

adult couples. They were finally completely assimilated into the

expanding Roman culture.

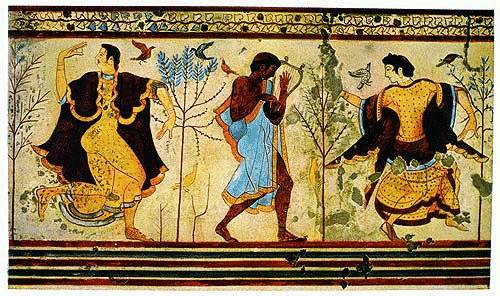

Etruscan painting (showing Greek influence)

|

Etruscan sarcophagus

|

Early Roman History

In 510, the

last king (Rex), Tarquin the Proud, was driven

out of Rome and an aristocratic republic established,

with the imperium (supreme power) vested in two

magistrates, later called consuls, elected each year. The kings had naturally had a Council and

this developed into the Senate, which was the main

governing body of Rome, composed of men who had held public

office, so similar to the Athenian Boule. The Senate

served as the symbol and voice of the State, even when its power

was reduced under the emperors. In times of crisis a dictator

(similar to a Greek tyrant) might be appointed by the

Senate to lead the people.

The

citizens of Rome were divided into two classes, the aristocratic

patrician families and the mass of the plebians,

and much of the constitution of Rome arose in the struggle for

power, as the lower class plebs established their right

to representation, such as tribunes, and an Assembly. In the end,

compromise led to solutions which, in Greece, were never

found, partly perhaps because the expansion of Roman power over

the Italian peninsula always gave the lower classes chances of

becoming rich. The city soon developed a system of food

subsidies, by which each citizen was entitled to free bread, as

a means of reducing social tensions.

Greek attempts to assert

power in Italy obliged Rome to exercise its military power

across Italy and

by the end of wars against the Greek Pyrrhus in 275,

Rome had taken control of the whole Italian mainland. Pyrrhus

gained two "Pyrrhic victories"

against Rome between 280 and 278. (A "Pyrrhic victory" is one in

which, although you win a battle, you lose the war). The Romanizing of

Italy was done slowly, by colonizing, by treaty and by

influence, until most people were speaking Latin, using Roman

laws, and seeing the advantage of being Roman citizens. In 273, Ptolemaic

Egypt recognized the importance of Rome. The expansion of

Roman control over the Greek settlements in Southern Italy and

Sicily by 241, brought Greek culture fully into Roman life. The Romans organized,

first Sicily, then other overseas territories, as provinces,

the units of government that were to compose the Empire.

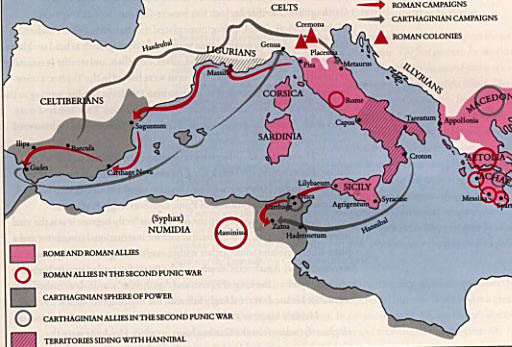

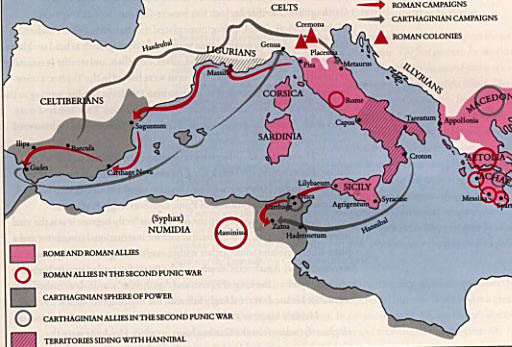

The First Punic War

(240 BC) was fought in Sicily

against the power of Carthage, Rome's main rival

(the word Punic is the same as Phoenician, for Carthage was a

Phoenician colony). It

ended in Roman triumph, Carthage being forced to leave Sicily. Then Rome drove the

Carthaginians out of the western islands of Sardinia and Corsica

too.

Between 237 and 219, the Carthaginian generals

Hamilcar, Hasdrubal and Hannibal took

control of Spain and in 218 Hannibal launched an attack across

southern Gaul against Northern Italy. His exploit in marching an army of 30,000

men over the Alps in winter provoked the admiration of

the Romans. The Romans sent an army to

Spain to prevent reinforcements arriving. They drove the

Carthaginians out of Spain and thus isolated Hannibal while

avoiding direct battle. They

then invaded Africa and at last Hannibal was recalled to defend

Carthage itself in 203. He

had spent 16 years in Italy and left undefeated. He died by his own

hand in 183 while Carthage was finally destroyed in 146, after a

third Punic war; but Rome had already ensured in the Second

Punic War its international superiority for centuries.

After the destruction of Carthage, Rome took control of the

fertile lands of North Africa, then slowly expanded control

north of the Alps and towards what is now Yugoslavia. In about 120, the southern area of Gaul

(now part of France) was formed into a province (it is still

known as Provence).

After serving for 20 years, each Roman soldier was

entitled to a grant of farming land to which he could retire.

Such provinces provided the land needed. Meanwhile, the

Romans had been drawn into Greece, where they sacked Corinth in

146 and transported vast masses of Greek art to Rome,

where Greek philosophers were already lecturing by 155,

although there was never a true university in Rome.

The Civil War

With the wealth of

Greece and Carthage, Rome became immensely rich, and this led to

increasing corruption across the empire, which in turn led to

widespread resentment of the "greedy Italians." The

structures of administration had still to be created. In Italy, unrest came

mainly from the slaves

and the rural poor (uprisings in 135, 103). Germanic

tribes, too, were already invading Italy and had to be

pushed back (102). The

discontent built up into civil war, which could only be won

by concessions. By

about 90 B.C., all Italians were automatically Roman citizens, but all of

this had made the Army, especially the Commander, immensely

powerful. For many

years, the Commander, and consul was Marius. But in 88 Sulla

marched on Rome, opposing Marius, and the period of Civil

War began, the Republic having already lost much of its

credibility. In

83 Sulla set himself up as dictator, in place of Cinna,

but soon they both had to retire.

In 70, the general Pompey

was consul with Crassus,

and these two military leaders imposed their rule against that

of the Senate. In

67 Pompey became Tribune, war-leader, and established the

Province of Syria in

64. At the same

time Julius Caesar (born in 100 B.C.) was rising in

power at Rome. In

63, the consul Cicero unmasked a revolutionary

conspiracy by a group led by Cataline, but by now Crassus

and Julius Caesar were plotting to share power while Pompey had

retired into private life.

Since the Senate would not accept their demands, the

result was a coalition uniting Crassus,

Pompey and Caesar, called the First Triumvirate

(60). Caesar,

chosen as consul in 59, left to capture the northern parts of Gaul in a long campaign

(58-50) which he described in his great book "The Gallic War"

(Caesar is one of the greatest prose writers of ancient times). Gaul (now France) became

part of the Empire, stretching from the English Channel to the

Rhine. Caesar even

crossed into Britain in 55 and 54, but did not establish

any lasting control.

It was Julius Caesar

who finally established the modern (solar) calendar with

365 days (or 366 in leap years)

and twelve months. The Romans called the first day of the

month the Kalends, the 5th or 7th the Nones, and

the 13th or 15th the Ides (the later date for the 31-day

months) and calculated dates by counting back from those, which

had their origin in the older lunar calendar. The year began on

March 1st, and this was only changed in the 18th century, which

explains why the names of the months September - December do not

now correspond to their position in the calendar (Sept = 7, Oct

= 8, Nov = 9, Dec = 10). Roman years were often numbered by

counting from 753 (the foundation of the city, in Latin Ab

urbe condita, AUC)

Crassus having died in

53, the conflict between Caesar

and Pompey became open war. Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon,

entering Italy without the Senate's permission, which signified

civil war, and then defeated Pompey's armies in Spain (49) and

Greece (48). He

followed Pompey to Egypt, where he spent the winter fighting

Ptolemy XIII, and having an affair with Cleopatra, whom

he installed as Queen of Egypt and who bore his only son. He then returned to

Asia Minor, for a victory at Zela

(47), where he said the famous veni,

vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered). In Africa (46)

and Spain again (45), he won other battles, each victory

weakening the Republican cause.

Caesar, as dictator, was clearly a personal ruler,

whether or not he intended to change the basic constitution and

become king. In

44, after he had been made Dictator for life, he received almost

all the royal honours. At

last, a group of conspirators under Cassius and Brutus

assassinated Caesar in the Senate House on the Ides of March

(March 15) 44 B.C.. He

fell at the foot of Pompey's statue.

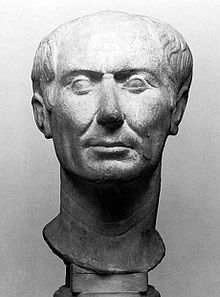

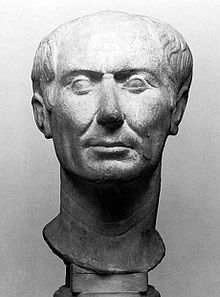

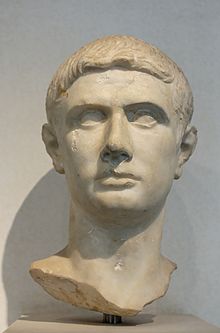

Julius Caesar

|

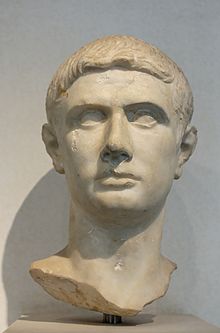

Brutus

|

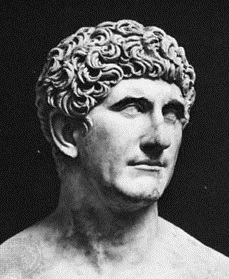

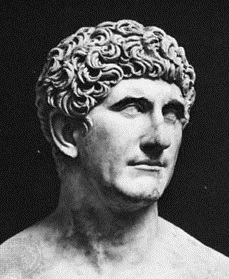

Mark Antony

|

From Plutarch : The

Death of Julius Caesar

When Caesar entered, the senate stood up to show their respect to

him, and of Brutus's confederates, some came about his chair and

stood behind it, others met him, pretending to add their petitions

to those of Tillius Cimber, in behalf of his brother, who was in

exile; and they followed him with their joint applications till he

came to his seat. When he was sat down, he refused to comply with

their requests, and upon their urging him, further began to

reproach them severely for their importunities, when Tillius,

laying hold of his robe with both his hands, pulled it down from

his neck, which was the signal for the assault.

Casca

gave him the first cut in the neck, which was not mortal nor

dangerous, as coming from one who at the beginning of such a bold

action was probably very much disturbed; Caesar immediately turned

about, and laid his hand upon the dagger and kept hold of it. And

both of them at the same time cried out, he that received the

blow, in Latin, "Vile Casca, what does this mean?" and he that

gave it, in Greek to his brother, "Brother, help!"

Upon this first onset, those who were not privy to the design were

astonished, and their horror and amazement at what they saw were

so great that they durst not fly nor assist Caesar, nor so much as

speak a word. But those who came prepared for the business

enclosed him on every side, with their naked daggers in their

hands. Which way soever he turned he met with blows, and saw their

swords levelled at his face and eyes, and was encompassed like a

wild beast in the toils on every side. For it had been agreed they

should each of them make a thrust at him, and flesh themselves

with his blood; for which reason Brutus also gave him one stab in

the groin.

Some say that he fought and resisted all the rest, shifting his

body to avoid the blows, and calling out for help, but that when

he saw Brutus's sword drawn, he covered his face with his robe and

submitted, letting himself fall, whether it were by chance or that

he was pushed in that direction by his murderers, at the foot of

the pedestal on which Pompey's statue stood, and which was thus

wetted with his blood.

So that Pompey himself seemed

to have presided, as it were, over the revenge done upon his

adversary, who lay here at his feet, and breathed out his soul

through his multitude of wounds, for they say he received

three‑and‑twenty. And the conspirators themselves were many of

them wounded by each

other, whilst they all levelled their blows at the same person.

Augustus

Julius Caesar had

named the son of his niece,

Caius Octavius (born 63, died A.D. 14), to be his

heir, since he himself had no legal sons. In 43, he was

recognized as Caesar's "son" with the name Octavianus

and in the same year he, Mark Antony (he had been the

colleague of Caesar as consul) and Lepidus, were named Triumvirs.

In 42 they defeated the Republicans under Brutus and Cassius, both of

whom killed themselves. In

41, Antony was in Egypt, where he met Cleopatra, with

whom he too began an affair, although he made a political

marriage with Octavian's sister Octavia in 40.

In 36, Lepidus fell

and, while Antony was busy in the East, Octavian took power over

Italy and the West. In

31, at the naval Battle of Actium, Antony and Cleopatra

were defeated. They killed themselves and Octavian became

supreme ruler, the Empire was at peace.

Julius Caesar had

named the son of his niece,

Caius Octavius (born 63, died A.D. 14), to be his

heir, since he himself had no legal sons. In 43, he was

recognized as Caesar's "son" with the name Octavianus

and in the same year he, Mark Antony (he had been the

colleague of Caesar as consul) and Lepidus, were named Triumvirs.

In 42 they defeated the Republicans under Brutus and Cassius, both of

whom killed themselves. In

41, Antony was in Egypt, where he met Cleopatra, with

whom he too began an affair, although he made a political

marriage with Octavian's sister Octavia in 40.

In 36, Lepidus fell

and, while Antony was busy in the East, Octavian took power over

Italy and the West. In

31, at the naval Battle of Actium, Antony and Cleopatra

were defeated. They killed themselves and Octavian became

supreme ruler, the Empire was at peace.

This Augustan Peace which lasted throughout his reign

was marked by the construction

of the Ara Pacis in Rome, and the Augustan

Age was later felt to have been a Golden Age. In 29, the

Senate confirmed the title of Imperator (Emperor)

which Octavian had been using since 38. His power was based

on his prestige, but he tried to make the Empire aware of the

values of Roman tradition by encouraging writers to express the

imperial vision. Among

them were Virgil and Horace. In 27 he received the

title Augustus, indicating his de

facto position, and the month August got its name at this time. He had become a

"constitutional emperor," ruling with the support of the

Senate and Roman People (Senatus Populus que Romanus SPQR

was the symbol carried at the head of the armies), but as he was

more and more honoured as a god, his position was quite unique. Under his rule, the

provinces became truly an Empire.

In A.D. 6, Judea (the

area

around Jerusalem)

became a minor Province by annexation, after the deposition of

Archelaus who had succeeded Herod the Great (died 4 B.C.). It

was to be ruled by Procurators, nominated for 10

years. In 27,

Pontius Pilate became Procurator. Galilee was not part

of Roman Judaea, it was ruled as a Tetrarchy by Herod

Antipas, under whose rule Jesus of Nazareth lived, and by

whose command John the Baptist was executed.

Early Roman

Literature

Rome has nothing to

compare with Homer and Hesiod, Plato and Aristotle. It developed

no great literary or philosophical tradition. There are the

plays written by Terence

and Plautus from the

period 200-150, which greatly influenced the Renaissance

comedies of Shakespeare etc. but otherwise nothing of note

from before the time of Caesar and Augustus. At the time of

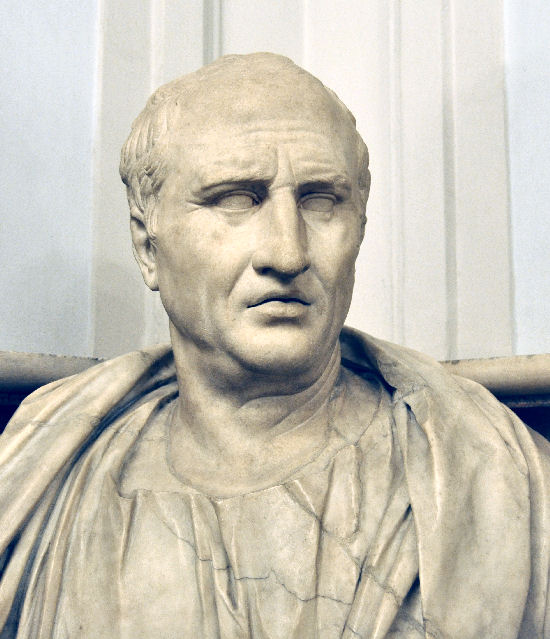

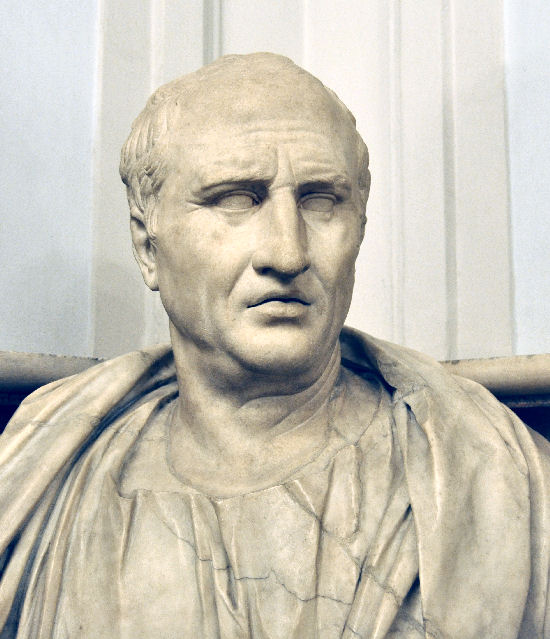

Caesar, the leading Roman statesman was Cicero (born

106) whose full name was Marcus Tullius Cicero, so that

he was also known (in Shakespeare etc.) as "Tully". He was opposed to

Antony after the assassination of Caesar and he was murdered by

Antony's agents in 43 B.C.. He had studied at the Academy in

Athens, where he learned to present mostly Stoic morality in a

simple, undogmatic way. Cicero's main works are

his Orations (speeches made in the course of his career

as a lawyer and political figure), his 931 letters to 99

different people, and writings on rhetoric and style. As a philosophical

figure, he wrote on political theory (De Republica, a

dialogue), on ethical and on theological questions. He was deeply

influenced by the Stoics but adopted an independent

line on some questions. His

main doctrine is that of humanitas, the

qualities of mind and character that make a man civilized. A true Man should

respect all men because humanity is worthy of respect. (The

Stoics taught the universal Brotherhood of Man, based on

the notion that each individual contains a spark of the same

divine fire). No

law, he said, can make a wrong thing right or a right thing

wrong. The moral

thought of Cicero has deeply marked the thinkers of

Europe: Luther, Montaigne, Locke, Hume. He was mainly familiar

as a moral thinker in the Middle Ages, but at the Renaissance

his influence as a stylist in prose, as the model of Latin

style, was enormous.

From Cicero's

De Officiis

From Cicero's

De Officiis

If every one of us seizes and appropriates for himself other

people's property, the human community, the brotherhood of

mankind, collapses.

It

is natural enough for a man to prefer earning a living for himself

rather than for someone else; but what nature forbids is that we

should increase our means, property, and resources by robbing

others.

This idea that one must not injure anybody for one's own advantage

is not only natural law, an internationally valid principle; it is

also incorporated in the laws which individual communities

have drawn up. (... )

Magnanimity, and loftiness of soul, and courtesy, and justice, and

generosity, are far more natural than self-indulgence, or wealth,

or even life itself.

But

to despise these latter things, to attach no importance to

them in comparison with the common good, really does need a great

and lofty heart.

In the same way, it is more truly natural to model oneself on

Hercules and undergo the most terrible labours and troubles to

help and save all the nations of the earth than to live a

secluded, untroubled life with plenty of money and pleasures.

Mankind was grateful to

Hercules for his services... So the finest and noblest characters

prefer a life of dedication to a life of self-indulgence: and one

may go further, and conclude that such men conform with nature and

will therefore do no harm to their fellow-men. (... )

Everyone ought to have the same purpose: to make the interest of

each the same as the interest of all.

For if men grab for themselves, it will mean

the complete collapse of human society.

If Nature prescribes that every human being must help every other

human being,

whoever

he

is, just precisely because they are human beings, then by the same

authority all men have identical interests.

Having identical

interests means that we are all subject to one and the same Law of

Nature: that being so, the very least that such a law must enjoin

is that we may not wrong one another. (... )

People are not talking sense if they claim that

they will not rob their parents or brothers, but that robbing

their other compatriots is a different matter.

That is the same as

denying any common interest with their fellow-countrymen, or any

consequent legal or social obligations.

And such a denial

shatters the whole fabric of national life.

Another attitude is that one ought to take account of compatriots

but not of foreigners.

People

who argue like this subvert the whole basis of the human community

itself-and when that is gone, kind actions, generosity, goodness,

and justice are annihilated.

And their annihilation is a sin against the immortal gods.

For it was they who

established the society which such men are undermining.

And the tightest bond

of that society is the belief that it is more unnatural for one

man to rob another for his own benefit than to endure any loss

whatsoever, whether to his person or to his property, or even to

his very soul, provided that no consideration of justice or

injustice is involved: for justice is the queen and sovereign of

all the virtues.

Let us consider possible objections.

(1) Suppose a man of great wisdom were starving to death: would he

not be justified in taking food belonging to someone who was

completely useless?

(2) Suppose an honest man had the chance to steal the clothes of a

cruel and inhuman tyrant, and needed them to avoid freezing to

death, should he not do it?

These questions are very easy to answer.

For if you rob even a completely useless man

for your own advantage, it is an unnatural, inhuman action. (... )

As for the tyrant, we have nothing in common with autocrats; in

fact we and they are totally set apart.

There is nothing unnatural about robbing, if

you can, a man whom it is morally right to kill, and the whole

sinful and pestilential gang of dictatorial rulers ought to be

cast out from human society... these ferocious, bestial monsters

in human form ought to be severed from the body of mankind.

(Translated by Michael Grant

)

Catullus (84-54) is above all

remembered for the 25 poems in which he celebrates his lady

"Lesbia" (surely not her real name, even if she was a real

person). He was

influenced by the Hellenic epigram, but made it into

something personal and vivid.

In this way he influenced the poets who came after him,

and wrote some of the most perfect short lyrics in any language,

full of intensity and vitality.

Many of his poems are love-elegies, based on Greek models

but Roman in feeling.

My sweetest Lesbia, let us live and love,

And though the sager sort our deeds reprove,

Let us not weigh them; heaven's great lamps do dive

Unto their west, and straight again revive

But soon as once set is our little light,

Then

must we sleep

one ever-during night.

(

Version by Thomas Campion, 1601)

Sallust (86-35) was one of

the first Roman historians, writing about the period of

Marius and the first stages of the decline of the Republic.

Julius Caesar

himself wrote "Commentaries" on his wars, seven books on the

campaign in Gaul, three more on the Civil War, describing each

stage in clear, simple prose.

These have been much studied, for Caesar was one of the

greatest generals ever, a master-strategist.

Augustan Literature

The Augustan Age was

later often seen as a Golden Age, because of the quality

of the writers, because it was a age of peace, because Rome was

rebuilt in imperial style.

Yet it was also an age of failure and disappointment,

because Augustus was an authoritarian dictator, an

autocrat who swept away the last democratic forms of the

Republic and took control of every sector of life. Augustus established

the Empire as it was to survive for 400 years, with a broadly

unified culture that would spread across Western Europe,

bringing many of the best things that had first been discovered

by Greece. Augustus

wished to give his people a higher vision of morality, of human

dignity, and used art for that purpose.

Publius Vergilius

Maro (known as Virgil or Vergil) (70-19) was born near

Mantua, studied at Cremona, Milan, Rome. He was deeply

influenced by the poems of Catullus and by the perfections of

rhythms and form practiced by the Alexandrians. At the time of

Caesar's death he went to live in the countryside near Naples,

and here he began his bucolic (pastoral) Eclogues. These caught

the attention of Octavian's rich and powerful advisor, Maecenas,

the model rich patron of literature, who brought Virgil into the

service of the rising future Augustus. The Eclogues were followed soon by

the Georgics, written after he had met

Horace. Later he

began to write the Aeneid for Augustus. He went to finish it

and study in Athens, from which he returned with Augustus in 19,

but fell ill and died on the way home.

The Eclogues

are modelled on the Idylls of Theocritus, but blend

the Greek and the Italian landscapes. The action is located in Arcadia,

an idealized land of shepherds acting as a symbolic contrast to

the corruptions of the contemporary city, so that

"pastoral" poetry is satiric as well as escapist. The delicate

sentiments and the pure music of Virgil's Eclogues have

inspired many later poets, including Sidney and Spenser. The mysterious 4th

Eclogue was long thought by Christians to be a "prophecy" of the

birth of Christ.

From Virgil's "Pollio"

: the Fourth

Eclogue of the Bucolics

(Which

Christians later believed prophesied the birth of Christ)

Publius Vergilius

Maro (known as Virgil or Vergil) (70-19) was born near

Mantua, studied at Cremona, Milan, Rome. He was deeply

influenced by the poems of Catullus and by the perfections of

rhythms and form practiced by the Alexandrians. At the time of

Caesar's death he went to live in the countryside near Naples,

and here he began his bucolic (pastoral) Eclogues. These caught

the attention of Octavian's rich and powerful advisor, Maecenas,

the model rich patron of literature, who brought Virgil into the

service of the rising future Augustus. The Eclogues were followed soon by

the Georgics, written after he had met

Horace. Later he

began to write the Aeneid for Augustus. He went to finish it

and study in Athens, from which he returned with Augustus in 19,

but fell ill and died on the way home.

The Eclogues

are modelled on the Idylls of Theocritus, but blend

the Greek and the Italian landscapes. The action is located in Arcadia,

an idealized land of shepherds acting as a symbolic contrast to

the corruptions of the contemporary city, so that

"pastoral" poetry is satiric as well as escapist. The delicate

sentiments and the pure music of Virgil's Eclogues have

inspired many later poets, including Sidney and Spenser. The mysterious 4th

Eclogue was long thought by Christians to be a "prophecy" of the

birth of Christ.

From Virgil's "Pollio"

: the Fourth

Eclogue of the Bucolics

(Which

Christians later believed prophesied the birth of Christ)

We have reached the last Era in Sibylline song.

Time has conceived and the great sequence of the Ages starts

afresh.

Justice, the Virgin, comes back to dwell with us,

and the rule of Saturn is restored.

The Firstborn of the New Age is already on his way

from high heaven down to earth.

With him, the Iron Age shall end

and Golden Man inherit all the world.

Smile on the Baby's birth, immaculate Lucina;

your own Apollo is enthroned at last.

And it is in your consulship, yours, Pollio,

that this glorious Age will dawn

and the Procession of the great Months begin.

Under your leadership all traces that remain of our iniquity will

be effaced

and, as they vanish, free the world from its long night of horror.

He will meet with the gods;

he will see the great men of the past consorting with them,

and be himself observed by these guiding a world

to which his father's virtues have brought peace.

(Translated by E. V. Rieu)

The Georgics are

presented as a guide to being a good farmer, but the quality of

the poetry shows that this is no mere handbook. These poems underlie

many others written later about the details of ordinary daily

life, especially working life, and the pleasures of rural

activity. But they

also show that there is a religious mystery revealed by contact

with nature. For

Dryden these were "the best poems of the best poet."

The Aeneid

relates the story of Aeneas in 12 books. An epic of the

legendary origins of Rome, with a strong unity of action,

inspired by Homer. The

style is highly polished, artificial, quite unlike the popular

style of Homer. During

the Middle Ages, it was read as an allegory of the human life

but from Petrarch on, it was also seen as a model to be imitated

by Renaissance writers of epic.

For Western culture,

no work is more influential than the Aeneid. Homer was unknown for

centuries, the Middle Ages knew only his name and had no Latin

translation of his epics, in fact he was taken for a liar

because there existed better-known Latin prose stories of the

same events told from the Trojan point of view. These stories,

bearing the names of Dares Phrygius ("The Fall of Troy") and

Dictys of Crete ("Diary of the Trojan War"), were the main

source of stories about Troy until the mid-17th century.

The Aeneid is

equally a continuation of the Trojan side, Aeneas being shown as

the son of Venus and a Trojan father, Anchises, in the Iliad,

where he is second to Hector.

The Aeneid is written with intense artistry,

with all Virgil's sensitivity and compassion. It shows the

foundation of Rome being prepared through great suffering,

near-despair, and human weakness, thanks to a scheme of divine

providence.

Since printing began

in Western Europe, the Aeneid has been published

in at least one new edition every year; from Roman times until

then it had been read continuously, even when no other classical

poetry was esteemed. Virgil

was considered to have been a Prophet of Christ, and was given

religious respect. He

is a basic influence for Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, Pope,

Victor Hugo, Tennyson...

The Aeneid (Summary)

In Book 1 the

Trojan survivors, led by Aeneas, escape a terrible storm and

arrive in North Africa. There they are brought by Venus to the

court of Dido, Queen of Carthage, who falls in love with Aeneas. She asks to hear his

story, which occupies Books 2 and 3, with

the destruction of Troy and his travels. They have settled

down into a quiet life together, but without any wedding

ceremony. In Book

4 Mercury is sent with a message from the gods,

urging Aeneas to remember his mission to go to Italy and found a

new Troy there. His

departure causes Dido to commit suicide and is given as the

reason for the centuries of war between Carthage and Rome in the

future.

Arriving back in

Sicily, Aeneas the "True" organizes Games to commemorate

the first anniversary of his father's death there, before the

journey to Carthage (Book 5). From there they

sail up to Cumae, near Naples, and visit the Sibyl (oracle of

Apollo) in her cave. After

an oracle on their future plans, Aeneas asks permission to go

down into the Underworld and meet his father's spirit. He is given

instructions and makes the journey (Book 6), one

of the most famous parts of the Aeneid.

Once at the Tiber,

difficulties and fighting return (Book 7), but

the spirit of Tiber encourages Aeneas to enter Latium. He sails up to the

site of future Rome, where Arcadians are living, and visits the

Capitol and the Forum, still just rocks and fields. For future battle,

Venus obtains armour from Vulcan, with a shield picturing the

future story of Rome (Book 8). The remaining

books (Books 9-12) describe the great battles and

struggle between Aeneas and Turnus for control of the land, with

Aeneas' last gesture of killing Turnus an unnecessary act of

revenge for the death of Pallas, when Turnus was already beaten. The poem was left

incomplete at Virgil's death.

The morality of the Aeneid

is "Avoid excess, be true." Its basic theme is the

importance of harmony and reconciliation, true nobility in

living. The opening lines have often been imitated:

Arms, and the man I sing,

who, forced by fate,

And haughty Juno's

unrelenting hate,

Expelled and

exiled, left the Trojan shore.

Long labors, both

by sea and land, he bore,

And in the doubtful

war, before he won

The Latian realm,

and built the destined town;

His banished gods

restored to rites divine,

And settled sure

succession in his line,

From whence the

race of Alban fathers come,

And the long

glories of majestic Rome.

O Muse!

the causes and the crimes relate;

What goddess was

provoked, and whence her hate;

For what offense

the Queen of Heaven began

To persecute so

brave, so just a man;

Involved his

anxious life in endless cares,

Exposed to wants,

and hurried into wars!

Can heavenly minds

such high resentment show,

Or exercise their

spite in human woe?

Against

the Tiber's mouth, but far away,

An ancient town was

seated on the sea;

A Tyrian colony;

the people made

Stout for the war,

and studious of their trade:

Carthage the name;

beloved by Juno more

Than her own Argos,

or the Samian shore.

Here stood her

chariot; here, if Heav'n were kind,

The seat of awful

empire she designed.

Yet she had heard

an ancient rumor fly,

(Long cited by the

people of the sky,)

That times to come

should see the Trojan race

Her Carthage ruin,

and her towers deface;

Nor thus confined,

the yoke of sovereign sway

Should on the necks

of all the nations lay.

She pondered this,

and feared it was in fate;

Nor could forget

the war she waged of late

For conquering

Greece against the Trojan state.

Besides, long

causes working in her mind,

And secret seeds of

envy, lay behind;

Deep graven in her

heart the doom remained

Of partial Paris,

and her form disdained;

The grace bestowed

on ravished Ganymed,

Electra's

glories, and her injured bed.

Each was a cause

alone; and all combined

To kindle vengeance

in her haughty mind.

For this, far

distant from the Latian coast

She drove the

remnants of the Trojan host;

And seven long

years the unhappy wand'ring train

Were toss'd by

storms, and scatter'd thro' the main.

Such time, such

toil, requir'd the Roman name,

Such length of

labor for so vast a frame.

(Translated by John Dryden)

From Book VI of the

Aeneid: The Underworld

Hence leads a road to Acheron, vast flood

Of thick and restless slime: all that foul ooze

It belches in Cocytus. Here

keeps watch

That wild and filthy pilot of the march

Charon, from whose rugged old chin trails down

The hoary beard of centuries: his eyes

Are fixed, but flame. His

grimy cloak hangs loose

Rough-knotted at the shoulder: his own hands

Pole on the boat, or

tend the sail that wafts

His dismal skiff and its fell freight along.

Ah, he is old, but with that toughening age

That speaks his godhead! To

the bank and him

All a great multitude came pouring down,

Brothers and husbands, and the proud-souled heroes,

Life's labours done: and boys and unwed maidens

And the young men by whose flame-funeral

Parents had wept. Many

as leaves that fall

Gently in autumn when the sharp cold comes

Or all the birds that flock at the turn o' the year

Over the ocean to the lands of light.

They stood and prayed each one to be first taken:

They stretched their hands for love of the other side.

But the grim sailor takes now these, now those:

And some he drives a distance from the shore.

Aeneas, moved and marvelling at this stir,

Cried - 'O chaste Sibyl, tell me why this throng

That rushes to the river? What desire

Have all these phantoms? and what rule's award

Drives these back from the marge, lets these go over

Sweeping the livid shallows with the oar?'

The old priestess replied in a few words:

'Son of Anchises of true blood divine,

Behold the deep Cocytus and dim Styx

By whom the high gods fear to swear in vain.

This shiftless crowd all is unsepulchred:

The boatman there is Charon: those who embark

The buried. None may

leave this beach of horror

To cross the growling stream before that hour

That hides their white bones in a quiet tomb.

A hundred years they flutter round these shores:

Then they may cross the waters long desired.'

(Translated by J. E. Flecker)

Quintus Horatius

Flaccus (always known in English as Horace) (65-8) was born in a

simple family, went to study at the University of Athens, then

served under Brutus, but survived the defeat at Philippi (42)

and was introduced to Maecenas by Virgil and entered the service

of Octavian, who enjoyed his company. His combination of great poetic skill with

a basically humorous attitude to life made him the great model

for English writers such as Pope.

The Epodes

are the earlier works, iambic poems in which Horace adopts a

tone of bitterness, ferocity, which is often found not to be

"real"; they are about love problems, politics, or are humorous

exercises. They

show refined techniques in epigram etc., derived from the

Hellenistic Greek poetry.

The Satires follow

a genre invented by Lucilius (died 101), the personal,

autobiographical satire, about opinions, adventures, food,

family, friends, morality, but Horace is much less bitter, far

more humorous; a stream of anecdotes interrupts the flow of

ideas, and we never know when Horace is being ironic because he

mocks himself as much as everyone else. He uses a form of the

epic hexameter, passing from the high style to the very relaxed,

and this link between epic and satire is recalled in the 17-18th

century English "mock-epic."

The Odes

(Carmina) are designed to display Horace's great

technical skill, modelled on the Greek poets, both Sappho and

the Alexandrians. They

are not "pure" lyrics, but explore many forms and situations,

often expressing directly political comments, which until this

were only found in epic forms of poetry. For Petrarch as for

Ben Jonson, these were a major model, and they inspired

Marvell's "Horatian Ode."

The Epistles

(letters) are his own inventions, written after the Odes

(from 20 B.C.), verse letters in which it is possible to deal

with any subject in a personal, conversational way: how to get

on with great men, the dangers of avarice, the value of the

simple life, town versus country etc. They are not "real" letters, addressed to

a particular person, but exercises in style. They were very

influential from the Renaissance period onwards, from Donne to

Pope especially.

Ars Poetica (Art of Poetry) is also a

verse epistle, skillful and humorous, but although it talks

about epic and drama, it is not quite clear what message it

contains. Pope

based his "Essay on Criticism" on it, and it was very important

for theorists such as Boileau. The following texts are both free

versions of parts of the Ars Poetica:

'Tis hard, to speak things common, properly:

And thou mayst better bring a Rhapsody

Of Homer's forth in acts, than of thine own

First publish things unspoken, and unknown.

Yet, common matter thou thine own mayst make,

If thou the vile, broad‑trodden ring forsake.

For, being a Poet, thou mayst feign, create,

Not care, as thou wouldst faithfully translate,

To render word for word: nor with thy sleight

Of imitation, leap into a straight

From whence thy modesty, or Poem's Law

Forbids thee forth again thy foot to draw.

Nor so begin, as did that Circler, late:

I sing a noble War, and Priams fate.

What doth this promiser, such great gaping worth

Afford? The

Mountains travailed, and brought forth

A trifling Mouse! O, how much better this,

Who nought assays, unaptly, or amiss?

Speak to me, Muse, the man, who, after Troy was sacked

Saw many towns, and men, and could their manners tract.

He thinks not how to give you smoke from light,

But light from smoke...

(Ben Jonson, 1604)

Observe what Characters your persons fit,

Whether the Master speak, or Jodelet:

Whether a man, that's elderly in growth,

Or a brisk Hotspur in his boiling youth:

A roaring Bully, or a shirking Cheat,

A Court‑bred Lady, or a tawdry Cit:

A prating Gossip, or a jilting Whore,

A travelled Merchant, or an homespun Bore:

Spaniard, or French, Italian, Dutch, or Dane;

Native of Turkey, India, or Japan.

Either from

History your Persons take,

Or let them nothing inconsistent speak:

If you bring great Achilles on the Stage,

Let him be fierce and brave, all heat and rage,

Inflexible, and head‑strong to all Laws,

But those, which Arms and his own will impose.

Cruel Medea must no pity have,

Ixion must be treacherous, Ino grieve,

Io must wander, and Orestes rave.

But if you dare to tread in paths unknown

And boldly start new persons of your own

Be sure to make them in one strain agree

And let the end like the beginning be.

(John Oldham, 1681)

Livy (64-A.D. 12?) is the great

historian of Rome. He

wrote a history from the beginnings, in 142 books, of which only

35 have survived. He

exposes the history of Rome in vivid prose, full of

descriptions, that make it a "prose epic," a form of literature. It is given a basic

moral structure (Livy came from a very strict family in Padua)

by the idea of old Rome as a place of discipline, simplicity,

piety, virtue, all values lost in later corruption by luxury and

avarice.

Propertius (54-16), the most

"artistic" of the Latin poets, elaborate, witty and energetic

like John Donne, is difficult.

He gave the name "Cynthia" to his lady, who seems to be

real.

Publius Ovidius

Naso (known as Ovid) (43-A.D. 17) became famous as a poet in the

generation after the death of Virgil and Horace, by 8 A.D. he

was the most famous poet in Rome, but then he displeased

Augustus (How? We

have no clear information) and he was exiled to Tomis on

the Black Sea, a dangerous place on the edge of the Empire,

where he died.

Ovid wrote all his

works except the Metamorphoses in elegiac couplets. The Amores,

a collection of love poems, suggesting a final rejection of

love-conventions, translated by Marlowe, influenced Donne.

The Heroides

(Epistles from Heroic Women) are mostly verse epistles or

dramatic monologues written/spoken by famous women to absent

husbands or lovers; a second group has pairs of letters in which

the man writes/speaks first.

These are explorations of the psychology of passion, of

what we call "romantic love," the oppositions between the sexes

exist in unresolved tension.

Pope's "Eloisa to Abelard" is one of many modern

imitations.

The Ars

Amatoria (Art of Loving) is a parody of

normal didactic poetry, teaching the arts of seduction and

intrigue to men (books 1 & 2) and women (book 3). It must have shocked,

but Ovid's "apology" or retraction, the Remedia Amoris

(the Cure for Love), is no more serious. In the Middle Ages,

Ovid's psychology of Love was immensely popular, especially in

France, where it underlies what is often known as "courtly

love."

The

Metamorphoses (Transformations), an epic

poem in 15 books in epic hexameters, show the transformations

found in old legends, from the beginnings of time until Julius

Caesar. Ovid

wished to be made immortal by this work, which is inspired by

Alexandrian poetry. It

is essentially a collection of fragmentary stories, anecdotes

united by an overall thematic framework and by Ovid's narrative

skill. The more

philosophical theme of "mutability and permanence" stands to

affirm a basically optimistic outlook. These stories are the

main source of medieval and Renaissance knowledge of Greek

mythology, interpreted in the Middle Ages in a moralizing,

allegorical way. The

Metamorphoses was often read and translated in England,

especially by Caxton (1480) and by Arthur Golding (1567-7) whose

translation had a great influence on Elizabethan poetry,

including Shakespeare, who probably also read the original

Latin.

Ovid, with Virgil, is

one the first "literary poets," his poems show how much he had

read of other poets. But

he is writing about human emotions, exploring the heart and its

passions. He has

enormous technical skills over language and metre, but

above all a marvellous imagination, which may be serious or

amused. In any

case, he teaches us to be more human at every point. Compared with the

other Augustans, he is a man of freedom and sensitivity, aware

of the good that exists in life.

He and Virgil are the two poets who were read

continuously, who were as familiar in the 12th century as in the

16th.

The beginning of

the Metamorphoses

The golden age was first; when man, yet new,

No rule but uncorrupted reason knew;

And with a native bent, did good pursue.

Unforced by punishment, unawed by fear,

His words were simple, and his soul sincere:

Needless was written law, where none oppressed;

The law of man was written on his breast;

No suppliant crowds before the judge appeared;

No court erected yet, nor cause was heard;

But all was safe, for conscience was their guard....

The teeming earth, yet guiltless of the plough,

And unprovoked, did fruitful stores allow:

Content with food which nature freely bred,

On wildlings and on strawberries they fed....

From veins of valleys milk and nectar broke,

And honey sweating through the pores of oak.

But when good Saturn, banished from above,

Was driven to Hell, the world was under Jove.

Succeeding times a silver age behold,

Excelling brass, but more excelled by gold.

Then Summer, Autumn, Winter did appear;

And Spring was but a season of the year.

The sun his annual course obliquely made,

Good days contracted, and enlarged the bad.

Then air with sultry heats began to glow,

The wings of winds were clogged with ice and snow;

And shivering mortals, into houses driven,

Sought shelter from the inclemency of heaven.

Those houses then were caves, or homely sheds,

With twining osiers fenced, and moss their beds.

Then ploughs, for seed, the fruitful furrows broke,

And oxen laboured first beneath the yoke.

To this next came in course the brazen age:

A warlike offspring prompt to bloody rage,

Not impious yet-Hard steel succeeded then;

And stubborn as the metal were the men.

Truth, Modesty, and Shame the world forsook:

Fraud, Avarice, and Force their places took....

Then landmarks limited to each his right:

For all before was common as the light.

Nor was the ground alone required to bear

Her annual income to the crooked shear:

But greedy mortals, rummaging her store,

Digged from her entrails first the precious ore,

Which next to hell the prudent gods had laid;

And that alluring ill to sight displayed.

Thus cursed steel, and more accursed gold,

Gave mischief birth, and made that mischief bold:

And double death did wretched man invade,

By steel assaulted, and by gold betrayed.

Now, brandished weapons glittering in their hands,

Mankind is broken loose from moral bands;

No rights of hospitality remain:

The guest, by him who harboured him, is slain;

The son-in-law pursues the father's life;

The wife her husband murders, he the wife.

The step-dame poison for the son prepares;

The son inquires into his father's years.

Faith flies, and Piety in exile mourns;

And Justice, here oppressed, to heaven returns.

(Translated by John Dryden)

The end of the Metamorphoses,

All things do change; but nothing sure doth perish. This same sprite

Doth fleet, and frisking here and there doth swiftly take his

flight

From one place to another place, and entereth every wight,

Removing out of man to beast, and out of beast to man;

But yet it never perisheth nor never perish can.

And even as supple wax with ease receiveth figures strange,

And keeps not aye one shape, nor bides assured aye from change,

And yet continueth always wax in substance; so

I saw

The soul is aye the selfsame thing it was, and yet astray

It fleeteth into sundry shapes...

In all the world there is not that standeth at a stay.

Things ebb and flow, and every shape is made to pass away.

The time itself continually is fleeting like a brook:

For neither brook nor lightsome time can tarry still.

But look!

As every wave drives other forth, and that which comes behind

Both thrusteth and is thrust itself, even so the times by kind

Do fly and follow both at once, and evermore renew,

For that that was before is left, and straight there doth ensue

Another that was never erst.

Now have I brought a work to end which neither Jove's fierce

wrath,

Nor sword, nor fire, nor fretting age with all the force it hath

Are able to abolish quite.

Let

come that fatal hour

Which, saving of this brittle flesh, hath over me no power,

And at his pleasure make an end of my uncertain time;

Yet shall the better part of me assured be to climb

Aloft above the starry sky; and all the world shall never

Be able for to quench my name; for look! how far so ever

The Roman Empire by the right of conquest shall extend,

So far shall all folk read this work; and time without all end,

If poets as by prophecy about the truth may aim,

My life shall everlastingly be lengthened still by fame.

(Translated by Sir John Harrington)

The Emperors after

Augustus

"I found Rome brick, I

left it marble" said Augustus.

The Rome of the empire, of which we see the remains

still, was begun under Augustus. But he had no son or

grandson to succeed him. Tiberias,

a brilliant general, was chosen and adopted, and became Emperor

when Augustus died in 14 A.D.. In his reign there was already a

feeling of insecurity, there were mutinies in the provinces. Tiberias withdrew to

the island of Capri in 26 and never returned to Rome. He died there,

insane, in 37, in a climate of terror. Under his rule Pontius Pilate had Jesus

executed in Jerusalem.

Tiberias was followed

by Gaius whose

universally-known name is Caligula (little

boot). He is the

first of the monster-emperors, of immense cruelty, probably insane,

accepting honors which made him equal to a god in his lifetime,

stirring up revolt among the Jews by a plan to put a statue of

himself in the temple at Jerusalem. He was assassinated in 41, to be followed

by the more reasonable Claudius. He was handicapped

and physically weak, and became emperor by chance when the

soldiers who had killed Caligula found him hiding in the Palace. He was interested in

administration. In

his days, in 43, Britain became a province of the Roman

Empire and the city of London

was founded on the Thames at the lowest place where a crossing

could be made; London was to become the largest Roman city north

of the Alps.

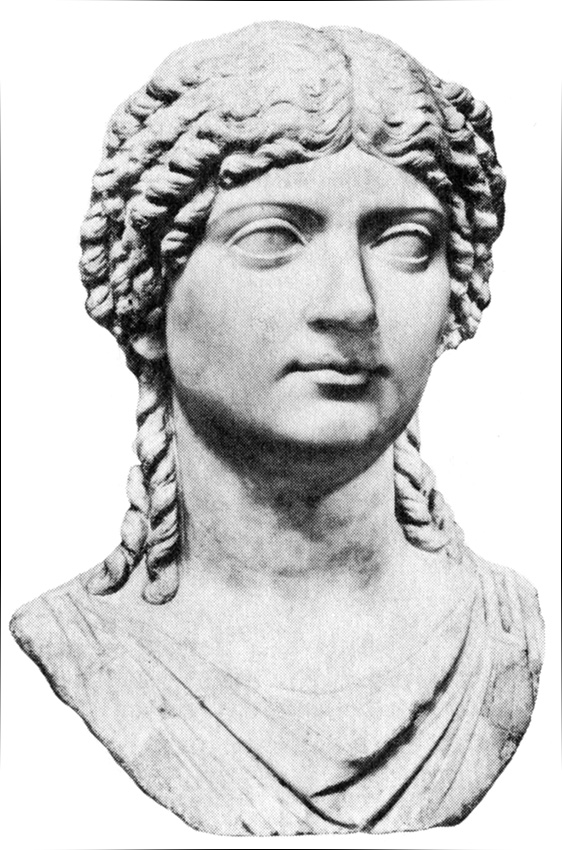

Caligula

|

Claudius

|

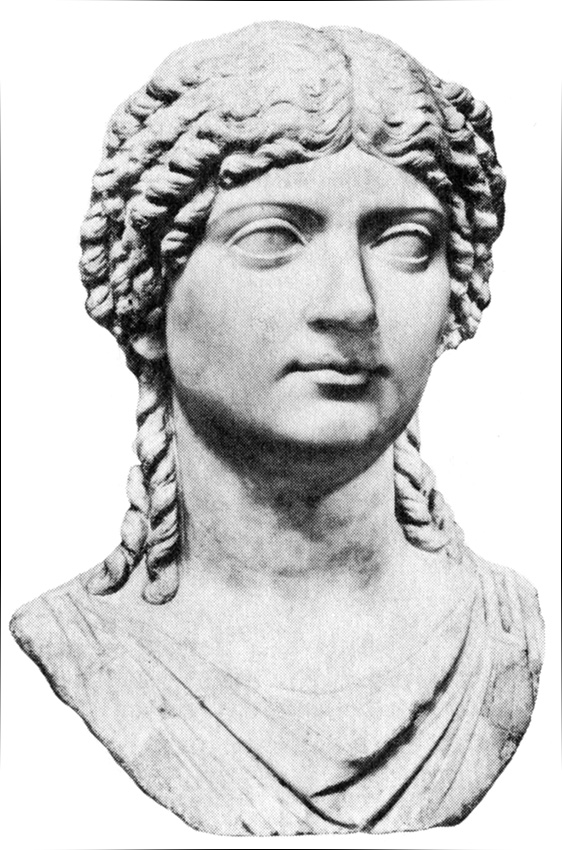

Agripinna

|

Nero |

Claudius had at least

four wives, the last of whom was his niece, Agrippina,

who had already a son, Nero, whom Claudius adopted in 50

as guardian to his own son Britannicus. Agrippina, at

first very powerful, but later rejected by Nero, turned to

Britannicus, who should have become Emperor, as Claudius' son. In 54 Claudius died,

perhaps thanks to some mushrooms given him by Agrippina, and

Nero became Emperor.

Britannicus had lost his right to the throne, and was

poisoned, probably on Nero's orders, in 55. Nero was interested

in poetry and art, thanks to his tutor Seneca who became

his main advisor for a time. In 59, encouraged by his mistress Poppaea, the

wife of his friend Otho (who was to be emperor for 2 months in

69), Nero arranged the murder of his mother, who had perhaps

been plotting his death. In

62 Seneca retired from imperial service, leaving Nero completely

out of control. He

then divorced and murdered his wife, Octavia, in order to marry

Poppaea (whom Otho had wisely divorced, he himself going to live

in Spain). In 65

Poppaea died of a kick Nero gave her.

Nero was fond of Greek

styles in art, and of gymnastics.

He built a Gymnasium and founded Games for young

men (Juvenalia) in Rome.

He also wrote poetry which was loudly acclaimed. In 64 a fire

destroyed one half of the city; there is a report that he caused

it ("Nero fiddled while Rome burned"), at least he took over a

lot of the land thus cleared to build a vast palace, and decided

quite arbitrarily to blame the few Christians already living

Rome for the blaze, slaughtering many. According to widely

accepted legend the martyrs included the apostles Peter

and Paul (cf. the film Quo Vadis). Peter

is said to have been crucified while Paul was beheaded.

In 65, a plot to

assassinate Nero was betrayed and many were executed or

forced to commit suicide, including the great Stoic and writer

of tragedies, Seneca,

and the epic poet Lucan. By 66 the Jews were

in revolt, Nero sent Vespasian to pacify them and left for

Greece. By now

Nero could not tolerate any rivalry, and forced generals to

commit suicide because they were successful! In Greece he won the

top prize in all the Games and Festivals, while there was a

famine in Rome. Executions

continued. Revolts

broke out in Gaul, Spain, Africa.

At last Nero fled from Rome and committed suicide in June

68.

Literary Figures of

the Post-Augustan Period

Phaedrus (15 B.C.-50) ought to be

known for his adaptations into Latin of Aesop's Fables

since his work established the fable, especially the beast

fable, as a serious genre.

Lucius Annaeus

Seneca (known as Seneca) (4 B.C.-65) was above all a philosopher,

Stoic and moralizing, but many of his works are lost. He is notable in

literary history because his Latin versions of nine tragedies

(Hercules Furens, Medea, Troades, Phaedra, Agamemnon,

Oedipus, Hercules Oetaeus, Phoenissae, Thyestes) showed

the Renaissance a form of classical tragedy that it found more

congenial than the austere Greek originals. Seneca's tragedies

are designed to be read in 'closet performance', not acted in a

theatre. They are static, and in high style. The presence of

ghosts, tyrants, madmen, nurses, traitors, of high emotions

expressed in elaborate rhetoric, of violent events, and other

such elements in Renaissance tragedy are all signs of Senecan

influence. His work is designed to illustrate the Stoic idea

that passion is essentially destructive; passion and revenge

unleash the hounds of hell, and the innocent suffer as much as

the guilty, while the gods remain above, indifferent.

Seneca's prose works

are marked by noble humanism and moral enlightenment. His style is

epigrammatic, curt, and influenced the change in English prose

style in about 1600. Until then, Cicero had been the model.

Erasmus edited him, Montaigne chose him and Plutarch as his

favorite writers. The

English Essays of Francis Bacon show strong Senecan

influence in their use of philosophical epigrams.

From Seneca's Moral

Epistles

We need not lift our hands to heaven, we need persuade no one to

let us approach the ear of some statue, as if by so doing we made

ourselves more audible. God

is near you, with you, in you.

Yes, Lucullus, within us a holy spirit has its seat, our watcher

and guardian in evil and in good.

As we treat him so he treats us. The good man, in fact, is never without God. Can any one rise

superior to Fortune without his aid? Is he not the source of every generous and

exalted inspiration? In

every good person "Dwells nameless, dimly seen, a god" (Aeneid).

If you are confronted by some dense grove of aged and giant trees

shutting out every glimpse of sky with screen upon screen of

branches, the towering stems, the solitude, the sense of

strangeness in a dusk so deep and unbroken, where no roof is, will

make God real to you. Again,

the cavern that holds a hillside poised on its deep-tunnelled

galleries of rock, hollowed into that roomy vastness by nature's

toils, not man's, will strike some hint of sanctity into your

soul. So if you see a man undismayed by dangers, untroubled by

desires, happy in adversity, calm in the midst of storm, eying

mankind from above and the gods on their own plane, will you not

be touched with awe before him?

Into that body a divine force has descended. The splendid and

disciplined soul, which leaves the little world unheeded and

smiles at the objects of all our hopes and fears, draws its

driving force from heaven. So

great a creation cannot stand without God for its stay... Thus a

spirit, great and holy, sent down to give us a nearer knowledge of

the divine, lives among us but cleaves to the fountain of its

existence: from this it is pendant, on this its gaze is fixed,

thither it strives, and moves among our concerns as a superior.

(... ) And what, you ask, is that?

His spirit, and Reason as perfected in that spirit. For man is a creature

of Reason. And what

does this Reason demand of him?

A very easy thing-to live in accord with his own nature. But it is made hard by

the universal insanity. We

push each other into vices.

(Translated by E. Phillips Barker)

Petronius, too, committed suicide in

65 after loosing Nero's favour.

He is the author of one work, the Satyricon,

which many consider the first novel. It

is a kind of Menippean Satire, combining lyric and mock

epic, poetry with prose.

It is full of low-class and disreputable heroes, humour

of situation and lively, realistic dialogue that reminds one of

Charles Dickens. Its structure is episodic, like the picaresque

novel.

The

Later Empire

Astonishingly, the

Empire survived the excesses of Nero; the administration laid

down by Augustus and Claudius did its job, even in the confusion

that followed them. At

first, after Nero's death, the Praetorian Guard (in charge of

imperial security at Rome) and the Senate, chose Galba

from Spain as emperor. The

next year the Guard acclaimed Otho and killed Galba. The armies along the

Rhine chose Vitellius,

there was a battle which Otho lost, he committed suicide. In the East, the

armies had chosen Vespasian; they marched on Rome, there

was fierce fighting and Vitellius was killed. Vespasian ruled as

Emperor for 10 years.

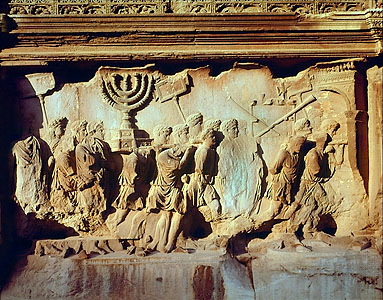

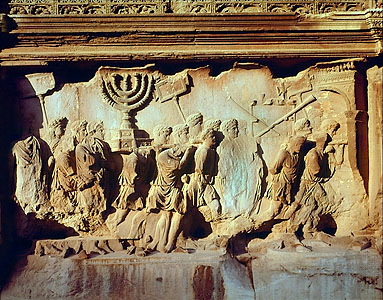

The long Jewish

Revolt, centered in Jerusalem, was finally crushed by a

Roman army led by Vespasian's son Titus who in 70 captured Jerusalem, destroying

the city and the Temple, removing the veil and sacred ornaments

to Rome. This

event was recorded on the Arch of Titus that still

stands near the Colosseum in Rome. From this moment, the Jewish

identity could only continue in Diaspora (dispersion). In fact, since the

deportation by Nebuchadnezzar in 587, there had been large

communities of Jews living in Babylon; they remained

there until the 20th century when most if not all went to live

in Israel. In Alexandria one third of the population was

Jewish at the time of Claudius.

The destruction of the temple did not mean the end

of Judaism, which continued with the local Synagogue

as the centre of worship, with community rituals marking each

stage of life, and with the annual festivals including the

family-centered Passover Meal with its final "Next year

in Jerusalem!" Finally, in 135, exasperated by continuing Jewish

revolts, Hadrian built a Graeco-Roman city on top of the ruins

of Jerusalem and forbade Jews to live in it.

Under Vespasian,

the Empire knew peace and ordered government, which could be

continued because he left two sons who followed him as emperor,

Titus (emperor 79-81) and Domitian (emperor

81-96). The role

of the emperor now became clearer; he was effectively a monarch

with absolute powers. Under

Vespasian and Titus, this was expressed in good government, but

Domitian, Titus' younger brother, after a good beginning began a

reign of terror from 93, in which philosophers were banished

from Italy and many people were executed. The emperor saw plots

everywhere but at last his wife and others succeeded in

murdering him in 96.

The long Jewish

Revolt, centered in Jerusalem, was finally crushed by a

Roman army led by Vespasian's son Titus who in 70 captured Jerusalem, destroying

the city and the Temple, removing the veil and sacred ornaments

to Rome. This

event was recorded on the Arch of Titus that still

stands near the Colosseum in Rome. From this moment, the Jewish

identity could only continue in Diaspora (dispersion). In fact, since the

deportation by Nebuchadnezzar in 587, there had been large

communities of Jews living in Babylon; they remained

there until the 20th century when most if not all went to live

in Israel. In Alexandria one third of the population was

Jewish at the time of Claudius.

The destruction of the temple did not mean the end

of Judaism, which continued with the local Synagogue

as the centre of worship, with community rituals marking each

stage of life, and with the annual festivals including the

family-centered Passover Meal with its final "Next year

in Jerusalem!" Finally, in 135, exasperated by continuing Jewish

revolts, Hadrian built a Graeco-Roman city on top of the ruins

of Jerusalem and forbade Jews to live in it.

Under Vespasian,

the Empire knew peace and ordered government, which could be

continued because he left two sons who followed him as emperor,

Titus (emperor 79-81) and Domitian (emperor

81-96). The role

of the emperor now became clearer; he was effectively a monarch

with absolute powers. Under

Vespasian and Titus, this was expressed in good government, but

Domitian, Titus' younger brother, after a good beginning began a

reign of terror from 93, in which philosophers were banished

from Italy and many people were executed. The emperor saw plots

everywhere but at last his wife and others succeeded in

murdering him in 96.

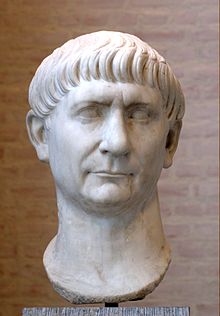

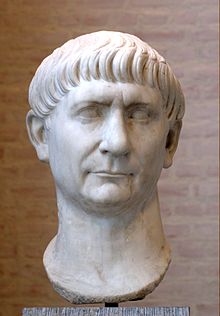

Trajan

|

Hadrian

|

Hadrian's Wall, N. England

|

Marcus Aurelius

|

The

new emperor is counted as the first of the "Five Good Emperors":

Nerva (only ruled for 2 years), Trajan (98-117),

Hadrian (117-138), Antoninus (138-161), Marcus

Aurelius (161-180).

One important factor was that all these men chose their

successor as "the best man available," having no sons of their

own. As soon as

Marcus Aurelius made his son his successor, corruption returned. In this time, the

Roman presence in Britain was being confirmed, and

Hadrian is still remembered for Hadrian's Wall (built

122-7), which divides England from the lands to the north,

stretching originally from coast to coast at the level of modern

Newcastle-upon-Tyne. The fierce Pictish tribes of the North were

too strong for the legions.

The Colosseum

|

The Pantheon

|

|

This is the great age

of the Roman cities across the Empire. Peace meant that

economic development became possible, the great road system

was expanded, trade went beyond the frontiers, to Scandinavia

and China. This is

the age that built the Colosseum, Trajan's Forum,

the Pantheon in Rome, while theatres, baths, aqueducts,

schools and libraries spread across Europe, the Middle East, and

North Africa. This

is the Silver Age of Latin Literature. At the same time, the

Empire was becoming more international, more Oriental too, and

Christianity was not the only Eastern religion spreading at this

time, but it was to outlive all the rest.

The Writers of the

Silver Age

Quintillian (30-100?) is only known by

one work, "On the Training of an Orator," in which he outlines a

traditional system of education based on speech-making. In the Renaissance,

many scholars were tutors to high-class children and his ideas

appealed to Erasmus, Vives etc.

At the end, he gives a picture of the finished product, a

Roman gentleman perfect in morals and diction. Pope refers to his

suggestions about good reading in the Essay on Criticism.

Statius (40-96) left only one

work that has survived, the epic Thebaid which

was highly esteemed in the Middle Ages by Dante and Chaucer. It

tells of the fratricidal conflict between Eteocles and Polynices

for control of Thebes, ending in their deaths (they kill each

other). Creon refuses burial to Polynices but Antigone and his

wife perform the rites. Theseus of Athens intervenes, kills Creon, and

destroys Thebes. The work is no longer admired or read.

Martial (40-104) has left us

fifteen books with more than 1500 epigrams, often a single

couplet. Some have a "sting" that is closer to satire than the

Greek epigrams had ever been.

But the humour ("wit") goes with deep understanding of

humanity. Martial's

epigrams were essential for the art of 17th-century poetry: Ben

Jonson, John Donne, Herrick, Cowley. Renaissance critics

distinguished between different tones of epigram: honeyed,

pungent, mordant, ridiculous and foul.

Pliny the Younger (61-114) is best known for

his 10 books of letters, 247 letters to 105 people. They were prepared

for publication, so are more artificial than those of Cicero,

but it is Pliny who taught the West the art of literary letters,

a form of essay. One

of the most famous letters contains his description of the

eruption of Vesuvius in 79 which destroyed Pompeii, in

which his uncle died. Equally

important is his letter to the Emperor Trajan, in which he asks

how he should deal with the Christians in the province

of Asia Minor he had been sent to govern.

Juvenal (50-127) is the greatest

of the ancient satirists, fierce where Horace was

amused, considering the evils of his age with "harsh, wild

laughter." Some of the topics of his poems are: hypocritical

philosophers, the difficulties of being poor, the faults of

women, the evils of pride and ambition, the cruelties of people. He was popular in the

Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Donne and other young men of his time enjoyed his caustic

approach. Dryden

was the first to translate him while adapting his references to

contemporary situations, Boileau in France, Pope and Dr.

Johnson, Burke, Hugo, Flaubert, Byron, all drew on his 16

surviving poems. His

vision of the world is always on the darker side, his struggle

is to remain human despite all the wickedness he sees.

Tacitus (55-117?) is a chronicler,

a historian. He

tells us almost all we know about the events between the death

of Augustus and the death of Nero in his Annals,

and is the source for Robert Graves' novels about Claudius,

for the film "Quo Vadis," as well as for Racine's Britannicus,

Ben Jonson's Sejanus (in which Shakespeare acted)

etc. He is also a

vital source of knowledge about

the Germanic tribes in his Germania; some of them were

later to cross the Channel and become the Anglo-Saxons while

others took control of Italy.

He even describes Britain in his Agricola.

Suetonius (69-140) is the founder of

modern biography, in his lost De Viris

Illustribus, in his "Lives of the Poets" and his "Lives

of the Twelve Caesars." After him, history came to be seen in a

biographical perspective, and thus he inspired St. Jerome's De

Viris Illustribus (392), Einhard's Life of

Charlemagne (820), William of Malmesbury's History

of the English Kings (1127) and all that follow. His lives are told

without prejudice or rhetoric, facts speak for themselves, and

since the people he describes were so fascinating, his lives are

reported like "case-histories."

At the same time, but

living in Greece and writing in Greek, lived Plutarch (50-120). For the last thirty

years of his fife he was priest at Delphi and wished to revive

the ancient Greek spirit.

He is most famous for his Lives, although

he wrote very many other works, mostly philosophical as

with his Moralia. His Lives contain

biographical portraits of 50 great men, some legendary like

Theseus and Romulus, some almost contemporary like Julius Caesar

and Brutus. Mostly they are written in pairs, with moralizing

comparisons attached. The

stories he tells are vivid, the narrative memorable, the

style varied. Many

of the Lives follow a pattern of family background - education -

youth - climax - change of fortune, which helped to inspire the

Renaissance historical tragedy.

In France, he was translated by Amyot in 1559, this

was then put into English by Sir Thomas North (1579), giving

Shakespeare his material for Julius Caesar and other

plays. Montaigne,

Dryden, Rousseau and the French Revolutionaries all drew on

him. In Plutarch's

Lives, history is seen becoming literature.

Marcus Aurelius is unique among the

emperors in being also famous as a writer. He was much engaged

in provincial wars, in Syria and Egypt, etc. During his spare time

he made notes on thoughts which struck him. Because of his own

personality, and the difficulties surrounding him, these

have great intensity, although the Stoic ideas expressed in

these Meditations are not very new. It is a work which

has appealed to thoughtful men of action over the centuries.

The Decline and Fall

After 200, civil war and

chaos returned, although for most people normal life continued. The slaves remained

slaves, the poor remained poor.

Many emperors came and went, now from many countries, as

they were imposed by military coups in different areas. Germanic tribes were

pressing on the Eastern frontiers, and there were many problems. At last Diocletian

(emperor 284-305) decided to divide the Empire into two parts, Greek-speaking

to the East, Latin-speaking to the West, establishing two "junior

Caesars," Galerius and Constantius, who would take power when he

retired. This did

not work, and by 324 Constantine (his English name) was

Emperor of the whole Empire. In 330, he dedicated the new

city of Constantinople, on the site of the old Byzantium,

to be the "New Rome," the capital in the East where the Emperor

had to spend most of the time.

It was modelled on Rome, with a Senate and free grain for

the citizens, but there were no great temples in it, for

Constantine had already chosen Christianity for his

personal religion, although he was only baptized on his deathbed

in 337. After him, the supremacy of Christianity in the Empire was

almost guaranteed, although Julian 'the Apostate'

(360-3) made one last attempt to bring back the old paganism.

Theodosius became emperor in 379 and only died in 395. It was

during his reign that Christianity became the official religion

and, especially from 391, many laws were passed that gradually

closed down the 'pagan' temples.

Before Constantine, many

emperors had tried to find a mythical basis for their authority in

religion. It was

Constantine who realized that the emperor could be seen as the

earthly representative of the heavenly Lord found in the Christian

Bible. In 282, Carus

had declared that the emperor was Dominus (Lord), not

merely princeps (first). Aurelian (270-5) had gone farther

by proclaiming himself dominus et deus, Lord and god, and

under Constantine the imperial liturgy was finally organized as it

continued at Constantinople until 1453. The emperor was considered

to be sacred; he dressed in purple and gold vestments similar to

those of priests, with incense before him, and all approaching had

to fall prostrate before him.

The economical and

political structure of the Empire gradually grew weaker and

the main place of new vigour was the Church as it confronted

its task of evangelizing the Empire. Already in 325, Constantine had

presided over a Council of the Church's bishops at Nicaea,

in Turkey, asking them to overcome their doctrinal disagreements,

centered on the so-called Arian heresy. This combination of Church

and State marks one beginning of the Middle Ages. Most of the great

writers of this age are found in the Church: Ambrose, Jerome,

Hilary, Augustine, Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Gregory of

Nazianzus, Basil. Christianity spread quickly

In the deserts of Syria

and Egypt, groups of men and women, fearing the corruptions of

urban life, began to live alone as hermits or together in

cenobitic communities, in lives consecrated entirely to God in

prayer. Their single-minded consecration to God was expressed by

the Greek word monos (single, one) and this is the origin

of the English word 'monk'. The monastic life had begun,

and would later yield the European monasteries whose libraries

were to be the key to the survival of Roman literary culture

during the coming Dark Age.

By about 404 the Roman

legions left Britain to help defend Italy and after about

450 its eastern regions began

to be occupied by new settlers: Saxons,

Angles, Jutes from North Germany.

Visigoths, Franks

(who gave their name to France) and Burgundians, all Germanic,

occupied much of Gaul, where they learned to speak the current

form of Latin, that was to become French. In 410, the Gothic

leader Alaric captured Rome and sacked it, marking

the start of virtual end of the Roman Empire in the West. From far away to the

East, the Huns had been advancing westwards for centuries. Under the leadership of

Attila the Huns advanced into Gaul and Italy, sacking Rome