1866: A Year to Remember? Or better forgotten?

Brother Anthony of Taizé

Published in RAS Transactions Volume 98 2024

Multiple documents, both French and Korean, provide ample information about Korea’s anti-Christian persecution of 1866, in which 2 French bishops and 7 French priests were killed, together with several thousands of Koreans during the years following, as well as the naval / military response by the French stationed in the region, during the latter part of 1866. During 1866, Korea was also visited briefly by a ship carrying Ernst Oppert, the first western ship to sail up the Han River to Seoul, a journey related vividly in Oppert’s later book, while at about the same time the American merchant ship General Sherman ran aground near Pyongyang and its entire crew was massacred. This was also the year in the which the young king of Korea married and an ambassador was sent from Beijing to bring the Chinese Emperor’s recognition of the bride as Queen. The ambassador wrote a very detailed account of his journey. In 1925, Bishop Mutel of Seoul published his French translations of the Korean government’s records covering the 1866 persecution and the French expedition. This provides vivid insight into the way these events were experienced at the royal court, and allows us to see them from both sides.

When the king is a child

When the first day of the first (lunar) month of Byeongin year 丙寅年dawned in China and Korea, it was already February 15 1866 by the Western calendar. China and Joseon (as Korea was then known in the East) had one feature in common: in both lands the supreme ruler was a child and power was being exercised by a female regent. In China, after the end of the Opium War in 1860 the Xianfeng Emperor, already sick, had fled from Beijing and turned heavily to alcohol and drugs. He died at the Chengde Mountain Resort, northeast of Beijing, on 22 August 1861. He was only thirty. His successor, his only surviving son, known as Tongzhi, was five years old (born in 1856) and the dying emperor had appointed an eight-member regency council to rule for him. His official empress now became known as “Empress Dowager Ci'an” while his principal consort, “Noble Consort Yi,” the mother of the new emperor, became “Empress Dowager Cixi.” Cixi returned quickly to Beijing, after agreeing with Empress Dowager Ci'an that they should become joint regents. Before the court could arrive with the late emperor’s coffin, Cixi had allied herself with two of the dead emperor's brothers, Prince Gong and Prince Chun. The members of the council were arrested on arrival, three were executed and soon Cixi was asked by her supporters to “rule from behind the curtains” (垂簾聽政), i.e., to assume power as de facto ruler. Another crucial turning point came with the final defeat of the Taiping Rebellion in 1864, but the country was effectively in ruins. Ci’an remained as nominal co-regent with Cixi until her death in 1881 but Cixi was the true ruler, within the limits imposed by Chinese bureaucracy and etiquette. The Tongzhi Emperor assumed full power in 1873 but fell sick with smallpox later in 1874 and died early in 1875, childless. Cixi then illegally installed her nephew, the child of her sister and Prince Chun (aged three) as the new Guangxu Emperor and continued to exercise immense power until her death in 1908.

In Korea, something similar happened. King Heonjong had died in 1849, childless, with no obvious successor. He had come to the throne after the death in 1830 of his father, Crown Prince Hyomyeong, who had been the eldest son of King Sunjo, husband of Queen Sinjeong. The grandmother of the late king, Queen Sunwon (King Sunjo's widow), decided to choose the next king. She selected Yi Won-Beom (born 1831), one of the few living descendants of King Yeongjo and a second cousin once removed to Heonjong. She decided to adopt him so that he could be the heir and she sent officials to tell his family to return from Ganghwa Island, where they had mostly lived for several generations. Yi Won-Beom had until then lived in the countryside as a poor peasant with no formal education. On July 28, 1849, Cheoljong (as he was known after his death) duly ascended the throne, and Queen Sunwon (a member of the Andong Kim clan) served as regent for two years. Cheoljong had poor health and he died at the age of 32 on January 16, 1864, without any heir.

As he lay dying, a quarrel arose between the three queens, Cheonin (also from the Andong Kim clan), Sinjeong and Hyojeong (wife of Heonjong) about the succession. As the most senior of the three, Sinjeong snatched the royal seal from the current Queen to ensure her control and it was agreed that the next king should be Yi Jae-hwang (born 1852), the second son of Prince Heungseon (Cheoljong’s seventh cousin). He would have to be adopted by a queen in order to become king. Queens Sinjeong and Cheonin both wished to adopt him, in order to gain power, but as she held the seal, Sinjeong claimed the right, making the new king (later known as Gojong) a descendant of Crown Prince Hyomyeong, not of Cheoljong.

The new king was “crowned” on 13 December 1863, aged only twelve, and Queen Sinjong became the official regent. The new king’s father was given the title Heungseon Daewongun, a title usually bestowed on a male Regent, and Queen Sinjeong invited the Daewongun to assist his son in ruling. She later formally renounced her right to be regent late in 1866 although the king was still only 14, and although she remained the titular regent, the Daewongun was in fact the true ruler and it was only in 1873 that the king claimed full authority and sidelined his father. Thus in 1866 the Emperor of China was 10 and the King of Joseon was 14, and in both countries effective power lay in the hands of a powerful woman.

Catholic Korea (see my Catholic history page)

Much of what happened in Korea in 1866 had to do with the presence of a sizeable Catholic community scattered mainly across the southern provinces with 2 French bishops and 10 French priests. The Catholic community had arisen after the baptism of Yi Seung-hun in Beijing in 1784. Apart from a Chinese priest who lived hidden in Seoul from 1795 until his execution in 1801, another Chinese priest in the early 1830s, and 3 French missionaries from 1836 until they were executed in 1839, the Korean Christians had had no bishops or priests until Bishop Ferréol and Fr. Daveluy (later Bishop Daveluy, coadjutor bishop) arrived on a ship with the first Korean priest, Fr. Kim Dae-geon, in 1845. Kim Dae-geon was executed in 1846, Bishop Ferréol died in 1853. Bishop Berneux, the Apostolic Vicar in 1866, had arrived in 1856 together with Fathers Pourthié and Petitnicolas. Fr. Féron arrived in 1857. Fr. Ridel and Fr. Calais entered in 1861, Fr. Aumaitre in 1863, Fr. Huin in 1865, like Fr. de Bretenieres, Fr. Beaulieu, Fr. Dorie. Most of the French priests had therefore only spent a few years in Korea in 1866. A few other priests had died of natural causes, often soon after their arrival.

Mistaken optimism

The lunar New Year’s Day of Byeongin year fell on February 15 1866. In the weeks before that, it seems, according to the French missionaries, that there had been reports of Russians landing at Wonsan and demanding the right to trade, which caused considerable alarm in Seoul. There is no trace of this Russian incursion in government records but some misguided Christians decided to write to the Daewongun advising him that with the Bishop’s intervention France might help protect Korea from the Russians. Among them was Thomas Hong Bong-ju, the master of the house being used by Bishop Berneux, and the yangban Thomas Kim Gye-ho. They hoped in this way to obtain freedom to practice their faith. However, it served in fact to alert the Daewongun to the presence of the French missionaries at a time when he was sure to be aware of the role played by the French in the humiliation of China in 1860. The letter was transmitted by the father-in-law of the daughter of the Daewongun. When the Daewongun said nothing after reading, Thomas Kim realized his mistake and fled. He was only caught and executed several months later.

A few days later the Catholic nurse of the king, Martha Park, heard the king’s biological mother (who was sympathetic to the faith and was baptized in her old age) commenting that the Bishop should be helping her husband against the Russians. Martha told Thomas Hong, who went to ask John Nam Jong-sam to help write a second, more formal letter. John Nam was a highly educated Christian who had taught the Korean language to several missionaries, including Fr. Ridel. He was then residing in the palace, giving Chinese lessons to the son of a great man of the court. His (adoptive) father, too, was a respected scholar, a Christian who had been baptized in Beijing in 1827. John was important enough to have direct access to the Daewongun. When he spoke to him, the Daewongun seemed to be interested, asked about the faith, even said he wanted to see the Bishop.

Bishop Berneux was a long way away from Seoul to the North, Bishop Daveluy to the South. Travel was costly. Father Calais writing in 1867 says that the father-in-law of the Daewongun’s daughter provided the means to bring them back. Bishop Daveluy arrived first, on January 25, Bishop Berneux on January 29. They waited but heard nothing more of a summons to the palace. Bishop Daveluy then left Seoul again. On the last day of the old year satellites came to the bishop’s house asking for a contribution for the new royal palace. This was a clear warning that the authorities knew where the Bishop was concealed. On the morning of February 23 the bishop told a catechist that he had seen satellites observing the layout of the house and at 4 pm that day he was arrested.

At the same time the Daewongun’s true mind must have become clear, for the government records covering the persecution open on 11.01 (the eleventh day of the first lunar month, February 25) with the report of two petitions demanding the arrest of Nam Jong-sam, the second from members of his family, both accusing him (in veiled and insulting terms) of being a Christian and referring to other unnamed persons recently arrested, meaning the Bishop. The Queen Regent, presiding the session, orders his arrest and refers to the testimony of Thomas Hong Bong-ju, who had been arrested with the Bishop.

Arrests begin

The same session includes the police report of the arrest of the Bishop: “on the 9th of this month, around 6 o'clock in the evening, we arrested I don't know what kind of foreign individual; 7 or 8 feet tall, he appears to be over fifty, his eyes are deep, his nose strong; he understands our language; he was dressed in a long cloth coat lined inside with lambskin; he wore a cotton canvas waistcoat and pants of the same and had double-studded satin shoes; these were obviously signs which denoted a foreigner. So we examined him severely and when questioned he replied that he came from the kingdom of France. He entered the kingdom of Korea in the year 1856, he settled in the house of Hong Bong-ju and traveled here and there to the capital and the provinces to spread the religion, and he has now been arrested.”

At the session of 15.01 (March 1) it is reported that Nam Jong-sam has been arrested at Goyang. According to Fr. Calais, soon after his arrest the Bishop met the Daewongun, to whom he failed to speak in the proper style of respect. He had surely never learned the honorifics and was accustomed to talking down to the Korean Christians. This did not impress the Daewongun. The Bishop was presented for trial at the Right Tribunal on February 25, 26 and 27, this last being (it seems) before the Daewongun and other high ministers. Meanwhile Fathers de Bretenières, Beaulieu and Dorie were arrested and interrogated. Fr. de Bretenières had been arrested early on February 26, the other two on February 27. The first mention in the government records of the arrest of the French missionaries comes during the report of a session dated 11.01 (February 25), devoted to the cases of the Korean Christians Nam Jong-sam and Hong Bong-ju. On 16.01 (March 2) the court record contains a list with the Korean names of the 4 missionaries together with 3 Koreans. There is little discussion beyond expressions of disgust that foreigners have been able to live in the country for so long. On March 4, 5 and 6 the records list the number of blows the missionaries have been given. The record for March 3 mention Nam Jong-sam and Hong Bong-ju being interrogated together, Nam having arrived back in Seoul. Another Christian arrested and interrogated at the same time is Peter Choe Hyeong, who had printed the many books prepared mainly by Bishop Daveluy and distributed in recent years.

The 20.01 (March 6) record indicates that Nam Jong-sam and Hong Bong-ju have already signed their death sentences. It ends with the order to transfer the 4 missionaries to the military to be executed “with suspension of their heads” and this should have taken place at once or on the next day, but Fr. Calais gives their actual execution date as Thursday March 8. As foreigners they were taken to Saenamteo, a military exercise ground on the shores of the Han River, and subjected to the full rite of military execution, the bishop being the first to be executed. The government record for March 7 reports the execution of Nam Jong-sam and Hong Bong-ju but there is no mention of the execution of the Bishop and priests. Over the following days there were several attempts to have the families of Nam and Hong executed but the Regent rejects that, before finally agreeing to their exile.

Next to be arrested were Fathers Pourthié and Petitnicolas. Fr. Pourthié was in charge of the small school (‘seminary’) at Baeron, to the south-east of Seoul and Fr. Petitnicolas had arrived in Korea with his health ruined by years in India. Unable to perform an active ministry, he was living with Fr. Pourthié. They were arrested in the morning of March 2 and on March 3 set off walking to Seoul. It took 6 days because of their weak condition. They were interrogated several time but Fr. Pourthié (who spoke Korean quite well) was too weak to speak. Their execution is ordered in court records on 25.01. They were executed at Saenamteo on the same day, Sunday March 11. All those executed at Saenamteo were buried nearby. On 20.07, months later, Christians came and found the bodies, which they buried with full rites the following night. Bishop Mutel much later had them interred in the crypt of the Cathedral in Seoul.

The final executions

Farther from Seoul, Fathers Aumaître and Huin had spent the day of Friday March 9 with Bishop Daveluy at Geodeo-ri (near Hongju) then gone separately to two other Christian villages. They had heard the news from Seoul. On Sunday March 11 Bishop Daveluy was discovered and arrested, then Fr. Huin was taken, and Fr. Aumaître surrendered voluntarily. They were treated with respect during the journey to Seoul, tried, and are mentioned in court records dated 7.02 (March 23). The court sentenced them to be executed near the sea in Chungcheong province. This is explained by Fr. Calais and others as being because the king had smallpox and a great gathering of shamans was due to perform rites to ensure his recovery, which must not be disturbed by bloodshed, while the king’s wedding was also being celebrated and bloodshed in the capital might bring bad luck. The three missionaries, with the Korean catechist Luke Hwang, had been beaten on the legs until they could not walk, so they rode on horseback. They approached Boryeong, through a region known to Bishop Daveluy, on Thursday March 29 and the bishop realized that it was Holy Thursday, the day before Good Friday. Hearing the satellites proposing to take them as a show to the nearby towns, he insisted that they must be executed without delay on the following day, Good Friday, in union with the death of Jesus, and this was granted.

Their execution on the beach at Galmaemot (a naval base) was solemn, with several hundred soldiers on guard, but instead of the multiple executioners circling them and slashing in turn, as was usual at Saenamteo, there was a single executioner. Bishop Daveluy was the first victim but after the first blow, which left him half-dead, the executioner stopped and demanded that his payment be settled by the local authorities before he went on. The negotiations dragged on for some time while the bishop lay writhing in agony. Finally it was settled and they were all beheaded.

Three Survivors

This left fathers Ridel, Féron and Calais. Fr. Ridel was on his way to the south-east when he heard of the persecution on reaching Daegu. He headed back to his base in Jinpat, arrived on March 9, hid his money and belongings in the hills, administered the sacraments to the Christians there, then left on March 12, just before the satellites arrived to arrest him, and went to hide in an isolated cottage with a Korean catechist. Hearing at last that Fr. Féron was not far from there, they set off and arrived at his refuge by night. In that isolated hut they were safe. Finally, on June 15, a messenger found them, sent by Fr. Calais. They exchanged messages and it was agreed that Fr. Ridel should try to sail across to China. On the coast of Naepo (Chungcheong-do) he was able to find the ship that Fr. Calais had arranged, manned by a few Christians, and on July 7 they arrived at the port of Chefoo, anchoring among several European ships, and Fr. Ridel was able to inform the outside world of the events in Korea, with the execution of nine French missionaries.

The French Religious Protectorate at work

As soon as Fr. Ridel arrived in Chefoo on July 7, news of the killing of the 9 French missionaries was sent to the French legation in Beijing. Henri de Bellonet had been, from June 1865, the acting French chargé d’affaires in Beijing. He had already been engaged in disputes with the Chinese authorities about the French missionaries active in China and clearly intended to assert the French Religious Protectorate of Catholics in China. On July 13 he sent a violent letter to Prince Kung (Gong) who as head of the Zongli Yamen was in charge of foreign affairs. His most outrageous claim was that “the same day on which the king of Korea laid his hands upon my unhappy countrymen was the last of his reign; he himself proclaimed its end, which I in my turn solemnly declare today.” Without having a single soldier under him, he declared that “In a few days, our military forces are to march to the conquest of Korea.” He ends by declaring, “The Chinese government has declared to me many times that it has no authority or power over Korea; and it has refused on this pretext to apply the Treaty of Tientsin to that country and give to our missionaries the passports which we have asked from it.... we do not recognize any authority whatever of the Chinese government over the kingdom of Korea.”

On the same day he wrote to Vice-Admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze, who was in charge of the French naval forces in the Far East, “I therefore do not hesitate, Mr. Rear-Admiral, to call upon the naval forces which you command; to put into your hands, under my responsibility, the task of taking a signal revenge for the attack to which two bishops and nine French missionaries have fallen victims.” This angered Roze, since he was an independent agent of the French government and had no orders to receive from civilian diplomats.

On July 16 (4.06), Prince Gung replied to de Bellonet a brief and diplomatic note, ignoring most of his missive, “Even if it turns out that Korea has put to death individuals belonging to the Catholic religion, it is still legally possible to make a preliminary inquiry into the true motives which may have led to this massacre without therefore beginning hostilities.”

At the same time the Prince seems to have asked the Ministry of Rites to send a notice about this to Seoul. Chinese records for 7.07 give the text. The Korean records for 8.07 (August 17) begin by summarizing the contents of the dispatch, which they say had just arrived, after a month’s journey: “We see in the dispatch sent by the Ministry of Rites of Beijing, which has just arrived, that previously the Minister of France had several times requested that passports be issued to the Missionaries to go to Korea and that the Foreign Affairs Court had observed that the practice of religion was not something desired by Korea, it was very difficult for it to give these passports. And here again, in a communication from the Minister of France, it is said that the King of Korea having arrested two French bishops and 9 missionaries, as well as indigenous Christians, men and women, old and young, he put them all to death: this is why the Minister gave orders to raise soldiers and warships and assemble them without delay. As China is convinced that this matter can be settled justly and amicably, and that, if there really were executions of missionaries and others, it is first necessary, relying on the law, to make investigations and taking information, and that there is no reason to immediately go to war, she made her views known to the Minister of this country, asking him to consider all things carefully before deciding anything.” On the same day the Korean government formulated its reply to Beijing, justifying the executions and thanking China for its support.

Admiral Roze takes charge

On July 10, Admiral Roze, after a trip to Beijing, had already arrived back at Tientsin. There he wrote to Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat, Minister of the Navy and Colonies in Paris, telling him: “Arriving back in Tientsin [Tianjin] from Beijing, I found a French missionary, Father Ridel, who just arrived... Father Ridel left Korea on a native junk to bring us the news of these events, landed at Chefoo, where he left his Korean junk and hastened to Tientsin by steamer with the thought of giving this information to the chargé d’affaires of France in Beijing.” Admiral Roze had been planning an initial survey of the Korean coast, followed by a major military attack the following spring, having questioned the Koreans who had accompanied Fr. Ridel about the location of Seoul and its defences. On July 11, however, he writes to the Minister that he was obliged to sail to Saigon in response to a veiled request for help from Admiral de la Grandière, who was faced with unrest. From Hong Kong on July 28 he wrote in detail about the information obtained from the Koreans, adding that Fr. Ridel wanted any survey to be followed at once by a military attack in order not to simply provoke the Koreans by another brief visit.

One month later, on August 23, he writes from Hong Kong that he had left Saigon on August 16, all being now calm, and is now heading for Chefoo, from where he intends to head for Korea to survey the approaches to Seoul and see for himself what might be possible. In his letters he often talks of ‘avenging’ the killing of the missionaries. On September 7 he writes to Bellonet a sharp letter stressing that this is his affair: “the negotiations to be undertaken with this nation, the naval and military operations that will need to be undertaken, the nature and extent of the reparations to be demanded for the past, the concessions and guarantees to be obtained for the future, are so many points that I reserve to assess alone, depending on the situation of minds and things, until the moment when I can receive instructions from our Government.” On September 16 (7.08) he was almost ready to set off with le Primauguet, le Déroulède and le Tardif, leaving his flagship la Guerrière in Chefoo. They left on September 18, found the estuary of the Han River thanks to the sailors who had come from Korea with Fr. Ridel, and slowly advanced towards Seoul which they reached on September 26 (15.08), spent 1 day there and returned to Chefoo on October 2. On October 6 Roze wrote to Admiral de Grandière: “my intention is to immediately seize the Island of Ganghwa, which is the first stronghold of Korea and whose occupation allows me to blockade Seoul and stop the convoys of rice which are used to feed the population.”

The immediate response of the Korean government to the warning message from China was to ask a learned scholar, Sin Seok-hui of the Royal Academy, to compose a solemn Edict refuting the perverse doctrine. This was promulgated on 3.08 and the order was given to distribute copies in Hanmun and in Hangeul to every part of the country. This lengthy edict, Cheoksa Yuneum 斥邪綸音, is modelled on similar edicts issued in support of the great persecutions of 1801 and 1839, belittling the Christian doctrines and advocating traditional Confucianism. It laments the failure of previous persecutions to completely uproot the pernicious doctrine and declares a resolve to eradicate it now.

The initial survey

On 13.08 the Korean records contain a report from the Governor of Gyeonggi, dated the previous day, of the arrival of ‘a foreign ship’ off the coast near Pupyeong. The following day there is indignation that the sub-prefect of Yeongjong had been negligent in reporting and in not intervening to stop the foreign ships. On 16.08 the ships are reported to be advancing. On 17.08 they learn that one ship (Primauguet, too large for the shallows) has dropped anchor while the other two were still advancing. One official has been allowed on board and has been able to learn something, but nothing important, from a Chinese crew-member. The magistrate of Yangcheon had been able to contact the smaller ships and had been told: “We are French from Europe and we have come to visit the mountains and rivers of your noble country.” They asked for 1 ox, 20 chickens, 30 eggs, as well as turnips and cabbages, which he had provided. On 18.08 another official had boarded the Primauguet, but there too only a Chinese crew member could communicate, and again he knew nothing significant. Later that day (September 26) there is a report that the ships have reached Yanghwajin (within sight of Seoul). Military action is being prepared but the authorities are worried because they have no idea why the foreigners have come, despite the warning received from Beijing. The next day comes the report that the ships have left Yanghwajin and there is a lengthy report of another visit to the Primauguet, where the magistrate of Bupyeong relates his attempts to communicate after bringing some gifts of food. In return he is given a bottle of perfume and a paperweight which he sends to the court. On 21.08 the court learns that the French have landed to take exact measures, they are surveying the river in detail, professionally. Then they disappeared. They arrived back in Chefoo on October 3 and Admiral Roze began preparing for his ‘military’ expedition, without waiting for any official authorization from Paris.

Ernst Oppert’s second visit

Meanwhile, on 5.07 (August 14) the court records include a report from Haemi about a “British” ship that had come demanding to trade. This ship, it says, had already come in the spring. This must surely be the Emperor, a paddle ship chartered by the German merchant Ernst Oppert, who had already made one visit to Korea earlier in the year on a different ship. In 1880 Oppert published a book in both German and English editions, A forbidden land: voyages to the Corea. Here he gives very detailed descriptions of his visits but unfortunately never once offers a precise date. During his second visit, in August 1866, he was able to discover the estuary of and sail up the Han River as far as Seoul, the first Westerner to do so, making a rough chart as he went. Somewhere on his journey some Koreans handed him a letter written by Fr. Ridel asking for help, but he knew that by that time Fr. Ridel had reached Chefoo. When the French sailed up the Han River in the autumn, they had a copy of his chart but did not find it very useful. Oppert became notorious for his attempt, on a third visit in 1868, to exhume the body of the Daewongun’s father in order to blackmail him into opening the country. On that third visit he was accompanied by Fr. Féron.

The General Sherman

On August 9, 1866, an American-owned armed merchant schooner named the General Sherman left Chefoo (now Yantai) and headed for Korea in the hope of doing trade despite the legal ban. The crew consisted of 2 American and 1 British officer, 13 Asian crew members and on board was a Welsh missionary Robert Jermain Thomas who had spent some time in Korea the previous year ‘evangelizing’ by distributing Bibles and tracts in Chinese. He had been planning to accompany Admiral Roze on his journey to Seoul but when Roze had been delayed and headed for Saigon he had boarded the General Sherman instead. He seems to have assumed that the French had by now reached Seoul.

The ship’s owner had purchased a cargo of cotton textiles, tinware, mirrors and glassware in China. On August 16 (6.07) the ship entered the Taedong River leading to Pyongyang. Some have suggested that they mistook it for the Han River leading to Seoul. Thomas insisted on stopping so that he could hand out tracts. The river was swollen by summer rain but once the water level dropped, the ship ran aground. The second report of its arrival in the court record is dated August 25 (15.07) where a military official 兵使 byeongsa Yi Yong-sang reports that a foreign ship had been spotted entering the Taedong River on 7.07 and when challenged someone who spoke Korean had said that after 7 of their countrymen had been killed by Korean noblemen some other ships had sailed up toward Seoul while they were heading for Pyongyang. This must be Thomas, trying to disguise their plan of trading. Another report to the court dated on the same day says how a foreign ship had arrived on 11.07 and someone had gone on board the next day to ask them to leave. He met Thomas who spoke of Christianity. On the 13.07 the ship advanced further upstream, close to Pyongyang. The Sillok dated 22.07 contains a report from the Gamsa (governor) of Pyongan province, Park Gyu-su, recording how a dinghy from the General Sherman had captured an official who was later rescued. On 25.07 a government order is recorded (probably from the Daewongun himself) instructing the Dosim of Pyongyang to take all necessary measures. A report received in Seoul on 27.07 (September 6) describes briefly how the General Sherman was set ablaze and how finally all on board were slaughtered, although Thomas and one other had already been taken prisoner. This actually happened on September 2 (23.07).

The Korean government were unsure about the nationality of the General Sherman, as America was still way beyond their horizon and there had been suggestions that it was French, while they seem to have known that Thomas was British. Rumors about the incident spread rapidly in Korea, but it took several years before a clear picture could be obtained by the American authorities and they found it hard to formulate an adequate response. The events of 1871 in Ganghwa Island were depicted as a punitive raid but that was not in fact the original intention, as the ships that were fired on as they approached Ganghwa Island were carrying State Department officials intent on negotiating trade agreements.

The French naval expedition (See my page devoted to it)

Admiral Roze brought together 7 ships, large and small, and a force of 5-600 marines. They left Chefoo on October 11 and arrived just south of Ganghwa Island on October 13. On October 14, Admiral Roze with five of the ships sailed up the Salt River (the strait separating Ganghwa Island from the mainland) and arrived at Gapgotjin, the village on the island’s coast from where a road leads to Ganghwa city. The French force landed there and occupied the village houses for their lodgings, the inhabitants having fled. The Korean court was immediately notified of the arrival of the ships, already briefly on 6.09 (October 14) and in detail, including the landing at Gapgotjin, in reports dated 7.09 (October 15). The court assumed that the ships would soon be sailing up the Han River to attack Seoul, but were unsure. The next day the French spent preparing to attack the walled township of Ganghwa, which housed the governor’s offices and the ‘detached’ royal palace.

On October 16 (8.09) the French forces advanced to attack, only to discover that the township was virtually empty, the defending forces and civilian population having fled during the night, leaving only a few old people and children. Meanwhile the Korean authorities begin to make military preparations and the Governor of Gyeonggi province reports that he had tried to talk with the foreigners but they had not allowed him on board their ship. The magistrate of Ganghwa, Yi In-gi, reported that just as the French were entering the township he had moved the two royal portraits enshrined in the palace to safety in the temple Baeknyeon-sa, high on a hill to the west of the township. Nothing could be more sacred than those portraits. He also reported how a local magistrate, Kim Je-heon, had approached the French and had been taken to a house in Gapgot where he tried to question them but nobody could read the characters he wrote. Then he was taken onto one of the ships, which must have made quite an impression, and found himself facing a seated European, presumably Roze, with beside him a man wearing Korean clothes and speaking Korean, obviously Fr. Ridel.

He was invited to sit and we have two records of the conversation, his own and that (shorter) of Fr. Ridel. It is of interest to compare them. Kim Je-heon wrote to the authorities: “He gave me a chair, I sat down and he asked me in Korean: Are you the Prefect of Ganghwa? I replied: No, I am a local magistrate. He then asked me: Who sent you? I replied: As a local magistrate, I came to get information. He then asked me: In the spring of this year, why did your kingdom put nine Europeans to death? I replied: Truly, in the spring there was an affair of this kind; but these men from your kingdom hid in the capital itself, they abused women and girls, they extorted the property of others and secretly plotted perverse designs; and thus, according to the law of our kingdom, they could hardly avoid the supreme punishment; this is why they were, in fact, executed. And really if our nationals went to your kingdom and committed these crimes, your country should exterminate them to the last one. What pretext are you giving there? He said to me: So we're going to kill you right away. I replied: You can kill me and I am not afraid; only killing an envoy who comes to ask questions, since antiquity this has never been seen. For you, go back, they replied, and then, taking out their sabers, they forced me to go, so much so that despite myself I returned and landed on the shore.”

Fr. Ridel later wrote to his brother about this encounter: “Before nightfall, a person was brought on board the Déroulède who had been arrested in the village, carried in a closed chair similar to the Japanese norimon. He was a very obese old gentleman; therefore he had all the trouble in the world to get out of that box, just large enough for him, especially as he was none too confident. It was the first time, no doubt, that he saw Europeans. He introduced himself as the second mandarin of Ganghwa, and he came to see what we wanted. The approach of this old man, who had come escorted by just four or five people without weapons, was not without pride. We could not get much out of him. When we spoke about the murder of the missionaries, he replied that it was perfectly justified by the conduct of the latter. Why do these people, he said, come here, trying to pervert us with new, subversive doctrines, take away our women, seduce our daughters? After a few moments, he was sent back.” The mandarin in his report goes on to relate how on landing he was surrounding by a threatening band of soldiers who demanded supplies and only let him go after he had signed a document promising to provide 5 oxen, 5 pigs et 50 chickens; it is not clear how this negotiation was conducted.

Over the following days the French settled into the abandoned houses that they commandeered, taking whatever animals and food they found. On 9.09 the Queen Regent issued a proclamation addressed to the general population presenting the invasion and blaming (without actually naming them) the Christians who had brought the missionaries into Korea previously. Meanwhile the Governor writes that the royal portraits have been moved from Baekryeon-sa, too close to the township, to the fort Inhwapo farther to the West. He also gives a more detailed description of the capture of the township, “the soldiers and the people who guarded the ramparts fled like birds and hid like rats. I only had a few men at my disposal and no soldiers from the fortress who could have resisted. Your servant, who was responsible for guarding the city, undoubtedly had to die on the spot; but there were the two royal portraits that I had temporarily transported to the pagoda called Baeknyeon-sa. It was therefore also my duty to go there in haste to protect them; but, while I was going to the said pagoda, the thought came to me that these villains, seeing the pagoda and its temple, would certainly set fire to it: it was therefore a dangerous place. This is why I was forced to transport the portraits again to the buildings of the fort called Inhwa-po......

“For me, placed on the border to ensure its defense and having failed, so much so that in an instant I witnessed the complete loss of the fortress and that consequently the attack itself on the capital was no longer that a matter of a moment, although all this is due to the fact that the force of soldiers was too weak, in truth it is because my management was negligent; and now, thanks to these pirates, your servant sees his situation ruined. However, I wish to submit without delay to the law of my country and, facing the East, I have no expression capable of making you aware of my pain and my sorrow.” He and the colonel in charge of guarding the township were sacked and replaced on the spot. The court was busy that day, with a great number of promotions and new appointments, while also giving orders for the defence of the kingdom, accepting volunteer soldiers, and providing food for the military on duty, bringing in forces and supplies from Gaesong to the north and Suwon to the south.

On 10.09 (October 18) there is a vivid report from a sub-prefect of Yeongjong of a confrontation with the French on the small island of Mulchi-do. They had come from the ships anchored to the South of Ganghwa and had a Chinese crewman with them who could write. The French said they wanted to buy food. The Korean then asked who they were and why they had come. Then things grew tense: “They have come to wage war against you for revenge. I asked: ‘Between them and us there is no cause of discord, what are they coming to avenge? And where will they wage this war of vengeance?’ ‘The place where they want to wage war is the capital, at the mouth of the river. You killed 9 of our nationals and that is why we want to kill 9,000 of your men’. I said: ‘What word is this? Our country did not kill 9 of your nationals, and now what are these words that you are saying to us?’ They replied: ‘We know it very well; Why do you want to deceive us like this again?’ It became very dangerous, because they were making threatening gestures.”

An imperial interlude (See an English version of the French translation of the ambassador's journal by Fernand Scherzer

On the same day there is a mention in the court record of the impending arrival of an Ambassador from China. Normally he should be welcomed by the Governor of the province he is crossing but as the governors of Hwanghae and Pyongan had to be on coastal alert, another official would have to replace them. The reason for the Chinese ambassador’s coming was unusual. Preparations were being made in Beijing to recognize as Queen the new bride of the young King of Joseon, a woman (nameless as was usual) from the Min clan born on 17 November 1851. She had been chosen after a lengthy process culminating in an interview with the Daewongun on March 6, 1866, which led to a wedding ceremony on 20 March 1866. Wikipedia tells us that when the ceremony was over the king went back to spend the night with his concubine, Royal Consort Yi Gwi-in, not his new bride. Still, China was to send an envoy to Seoul carrying the Emperor’s patent of her investiture as Queen.

The official chosen was the vice-president of the imperial court, Kouei Ling (1815-1878), appointed on 4.07. He composed a detailed report of his journey, as was a common custom, and it was later translated into French and published. His mission began on 12.08 when he went to the Court of Rites to take the imperial caduceus and from there he set out. He arrived at Uiju on 10.09, just after the French had landed in Ganghwa. Here he received the formal welcome from the envoy of the King of Korea: “The king of Korea sent to ask for news of me; I sent the officer back with instructions to convey my compliments and thanks to the king. The body of officials came to visit us. They had prepared 20 bushels of salt and as many bushels of rice for us; in addition, they had provided us with interpreters, carriages with drivers and an escort, as required by the rites.” On 17.09 he reached Pyongyang. On 21.09 they arrived in Gaesong and on the following day notes that the Daewongun “sent an officer to bring me his compliments. I sent him back with my compliments. (He) is the father of the king, and has in hand the high direction of the affairs of the state.”

On 09.23 he is about to arrive in Seoul having been on the road for 42 days. The ceremony of investiture will be held the following day. He describes it in some detail: “Around eight o’clock, the king sends officers who invite me to enter the capital. At nine o’clock we set out, the king came to the meeting of the Imperial Order, at 10 li outside the gate Yeongeun-mun 迎恩門. After having carried out the ceremonies required by the rites, he took the lead and returned in the city. The second envoy and I entered the outer city through the Seungni-mun 崇禮門gate, and we went to the inner city through the (淳化門 Sunhwa-mun?) gate, then, heading east, we arrived outside the Jinseon-mun gate 進善門 (the main entrance to Changdeok-gung), where we got off our sedan chairs. We enter the Injeong-jeon 仁政殿. On both sides of this pavilion, one had set up tents where we could change clothes and put on our ceremonial dresses and our badges. The king, wearing his costume with dragons, came out to meet us, he saluted the Imperial Order, which he read aloud; this ceremony was accompanied by the salute of the three kneelings and the nine prostrations. At the commands given by the masters of ceremony, the music was heard three times, and three different times people shouted in honor of the Emperor. The ceremony was then finished.

“We change our clothes, then we return with the king into the hall Injeong-jeon. The foreign guest was seated in the west, the master was seated opposite, in the east. The king had appointed three interpreters who passed on his questions according to the ancient rites which regulate the reception of guests. The king asked about the health of His Majesty and that of the two empresses. I stood up, and turning to the left, I answered: “The health of His Majesty is good, the health of the two Empresses is both excellent. The king asked about the health of the princes and dukes of the empire. I answered that they were all very well, then, by an exchange of questions and answers, the king and I had a most important conversation. Intermediaries were sent by the king to tell me respectfully that he was going to greet me, I apologized and refused up to three times, then finally I thanked him, and after having exchanged a greeting we sat down at the banquet which had been prepared; we drank several cups of wine to the sound of music, and the ceremony was finished only when I had been offered nine kinds of dishes.

“In the evening, we slept in the Nam-byeol-gung 南別宮palace. That day, the father of the king brought me two of his nephews and his two sons-in-law. The latter occupy very high positions. His son Li-taé-mien came to see me with some members of the Academy, we conversed with the help of the brush, and did not separate until about four in the morning.”

On 25.09 the festivities continue: “The king came in person to visit me; a banquet similar to that of the day before had been prepared; we were very polite to each other, and, according to the custom, I received presents from him. I had brought with me eight different kinds of Chinese products, which I sent to the king. In the evening, the king returned my politeness by sending me productions of Korea, of twelve different kinds, which I refused at first, then which I ended up accepting on his repeated requests. all the members of the Academy came to visit me and to converse by means of the brush, many of them asked me for autographs and poetries, and several offered me autographed verses as a present; I could not rest until the night, so I was exhausted.”

On 26.09 he left on the return journey. He probably heard nothing about the French expedition during his visit. He also, of course, did not see the Queen. “The king had arranged for emblem bearers and musicians in a vacant lot outside the western gate, Yeongeun-mun. A snack was set up there on tables placed opposite each other on both sides of the road. We were very polite there, and two hours were spent in conversations and libations: we could not decide to separate. Finally the king and the other civil servants came to offer me wine, wishing me a happy journey and expressing their regrets to see me leave.” On 13.11 he entered the palace in Beijing at 4 am, having arrived the previous day. “I respectfully asked for news of his Majesty’s health. The Emperor questioned me during this audience about the affairs of Korea; I gave respectful and detailed answers on all points. I returned home around noon.”

French bandits

On the following day, 11.09 (October 19), the court learned of an incident in which a group of 50 Frenchman had entered Tongjin, on the mainland directly opposite the Gwanseongpo fortress, seized the oxen and goods of the inhabitants, entered the government office and stole the money and uniforms they found there. The following day the same thing happened on the island of Yeongjong, where the French took 2 pigs and 9 chickens, then sailed off toward Incheon. The second of these raids must have been the work of men from the ships that remained anchored to the south of Ganghwa.

Meanwhile we have a lengthy account of the expedition written by Commandant Henri Jouan, a friend of the Admiral and a leading officer during the expedition. He had accompanied the large group that had attacked the township on October 16 and had found it deserted. He went with others to visit the official buildings, the Governor’s Yamen: “The interior of the houses, which seemed to have been abandoned only a few moments before, was furnished with a certain luxury, cushions, silk hangings, and an apartment, which had been inhabited by women, offered us a full assortment of beautiful false hair plaits, and slippers worthy to serve as shoes for Cinderella. One of the buildings contained a large library, with in addition to books, a certain number of curious objects, probably very valuable, judging by the way they were kept. They were marble tablets with golden inscriptions, small marble turtles, all carefully wrapped in silk bags, enclosed in double and triple boxes, with fragrant sachets to absorb shocks. The books were not to be despised. Much of the library consisted of large volumes, the size of our folio, with hardcovers and strengthened along the back with reinforcements of pierced bronze, with brass rings for hanging. There were also large maps, inscriptions, weird drawings. All these objects were sequestered to be inventoried and sent to France, if possible.” On October 22 the Admiral included a complete list of the objects sent to France in a report to Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat:

300 large bound volumes,

9 small bound volumes,

13 small volumes contained in a box of white wood,

10 small volumes ______ Do. ______

8 small volumes ______ Do. ______

1 map of China, Korea, and Japan,

1 celestial planisphere,

7 scrolls containing various inscriptions,

3 tablets in gray marble inscribed in Chinese characters,

3 small boxes, each containing articulated white marble tablets with copper hinges,

3 sets of warrior armor with helmet,

1 mask.

The return to Korea of the large books, the Uigwe, in 2011, was a cause of celebration. Jouan also confirms that the French were acting as the Koreans had reported: “Despite the reluctance of the admiral, we were obliged to resort to a system of raids, sending out detachments to procure cattle, according to the summary proceedings of all conquerors, that is to say, taking away without further ceremony all that we saw. In the same way, we obtained some mules and some small horses, which were very useful for the daily supply of the garrison of Ganghwa.” Fr. Ridel also reports an incident where the Admiral came across a group of three marines ransacking a house.

As Fr. Ridel reports, the problem was that the expedition was doing nothing to negotiate with the Korean authorities: “The town of Ganghwa taken, it was obvious that the Koreans were not prepared, so it was necessary to continue and without wasting time go back to the capital; as with the first expedition, the forces at our disposal would have been sufficient to take Seoul. Several officers were of this opinion, which seemed to be the most generally widespread feeling; but others were of a contrary opinion and claimed that enough had been done, that the Korean government would certainly come to deal with it; they were more influential, the admiral gave in to the latter opinion and resolved to stay in Ganghwa.” On the 12.09 there is mention of a written message received from the French, which the Korean found insulting and the decision is taken to send a copy to Beijing. On 16.09 the Regent presents a lengthy proclamation outlining the step taken so far. Meanwhile, executions of Christians continue.

The clash at the South Gate of the fortress

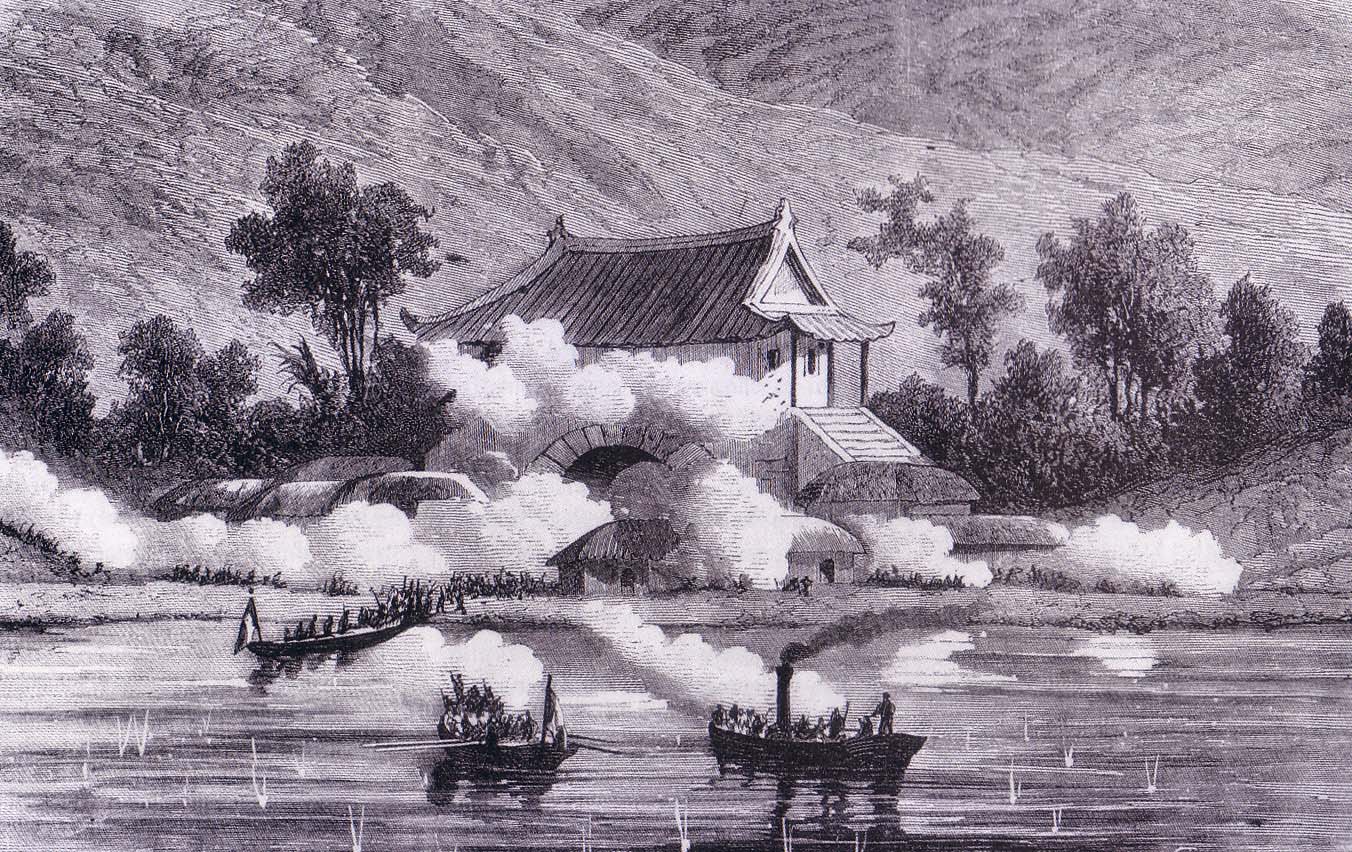

At last, on 19.09 (October 27) the court received news of a new incident the previous day. On the hills on the mainland opposite Gapgotjin there was Munsusanseong Fortress, a camp surrounded by fortifications, and with its south gate close to the point where the road from Seoul led to the ferry for Ganghwa. A reconnaissance party had landed on the mainland side, close to the south gate in the wall. They are fired on by soldiers in hiding on top of the gate and three French sailors are killed. A brief exchange of fire kills a number of the Koreans and the others flee. The French open cannon fire at Korean forces seen emerging from behind the hills a mile or two away. They burn the pavilion topping the gate and the houses around it, before withdrawing. These were the first deaths suffered by the French and were the more touching for being simple sailors, rather than officers.

The junior officer Henri Zuber, who was also the artist for the expedition, included a vivid description of the incident as he experienced it in a text sent to his family: “This morning as I was finishing my toilet, a sound of lively shooting drew me to the beach. Three of our small boats, carrying a division of 60 men, who were to undertake a reconnaissance on the other shore, had come under the fire of about 200 Koreans hidden in ambush behind a fortified gate and a few surrounding houses. In an instant five men, three mortally wounded, fell into the bottom of the boat. Meanwhile, the largest boat had landed. The men it was carrying rushed ashore and charged with bayonets fixed; soon twenty of the enemy were lying lifeless on the ground, the others fled in all directions, abandoning their weapons. We pursued them in vain, they ran like hares. The reconnaissance party continued to advance and came back to camp after having burned down the scene of the struggle. I cannot describe the emotion that seized me on seeing brought to land the dead and wounded. I will remember all my life long this sad spectacle, cursing war and its horrors. We had just won a success but a useless success, even a fatal one, for twenty Koreans killed were not from a military point of view a sufficient compensation for our losses. It has at least been recognized that the Koreans are not as harmless as we thought. The soldiers of the regular army showed great bravery and almost all were killed at their posts.”

The same incident is reported at length to the State Council the next day by a commanding officer, Colonel Yi Yong-hui: “Han Seong-geun, who combines the functions of captain, having under his command Sergeant Ji Hong-gwan and 50 soldiers of the assault troops, was responsible for guarding the Munsu-san fortress. That very day at 10 a.m., a dispatch from the commander of Munsu-san announced to me that 4 small European boats, taking advantage of the tide, were heading straight towards the southern gate of the fortress, which is why I sent immediately a company of soldiers to help; but they were barely halfway there when Ji Hong-gwan and Han Seong-geun, with disheveled hair and barely dressed, arrived successively, saying: ‘Two of the boats having landed first, Han Seong-geun set off alone, uttering loud cries; he began by firing several bullets, and, on the pirates' side, the echo was that several fell on the boat, then the 50 riflemen fired together, and, of the pirates from the two boats a good half fell, i.e. around 50 or 60 But in the blink of an eye, the pirates from the two boats following went ashore, there were easily more than 100 of them. Also, not having had time to reload our rifles, we found ourselves exposed to enemy fire: there were 3 deaths, one man injured in the shoulder and another in the buttocks; impossible to resist; so we gave up and returned, but, turning around to observe, we saw that these pirates had set fire to the southern gate of the fortress, then they sailed away.’ We were unable to destroy them and on the contrary we lost our soldiers. My function was to repel the enemy, confused and trembling I can only ask for my punishment.”

The Regent did not agree: “Yesterday when the European barbarians broke into the fortress of Munsu-san, Han Seong-geun with some troops resisted the enemy, and facing danger he fired at them; Ji Hong-gwan rushed forward without worrying about saving his life; one and the other, they have well deserved: their courage and their fidelity, their loyalty and their devotion are signal services and eminent merits. To give heart to the troops and to defeat the audacity of the enemy, there is no other way to go about it. May they be promoted to dignities on Victory Day. For the government soldiers, 3 of whom were killed and 2 injured, our hearts overflow with compassion that cannot be overcome. That for the dead we provide what is necessary to bury them with honor, that we remunerate their families generously and that the headquarters, whatever it is, be responsible for it. As for the wounded, let the order be given in the same way to take care of them and heal them; that a scout rider transmit this order to the vanguard and that the colonel first make these instructions known orally.”

On 21.09 the Council was told: “We first buried with honor the 3 killed and, as for the 2 wounded, we gave them all possible care. The Commander of Munsu-san, Sin Do-hyeok, in a dispatch announced that one of the inhabitants of the fortress was also killed and that he had given more than what was necessary to have him buried. There are 54 burned bays of government buildings burned and 29 residents' houses also burned. And he gives the names and first names of the killed and wounded. The killed, numbering 4, are the soldiers of the Gongju assault troops, Choe Jang-geun, Kim Dal-seong and O Jun-seong and the inhabitant of the Munsu-san fortress, O Dol-jeong. For each one, he said, I had 10 ligatures of sapèques and 3 pieces of cotton given, so that they could be transported and buried.”

In strikingly similar tones Admiral Roze wrote to P. de Chasseloup-Laubat when the French were about to leave Korea on November 13, listing the 3 killed: “Goaziou, Paul-Marie, second class sergeant, Pallier, Gilber, second class quarter-master, Grosselin, Jean-Marie, sailor second class, all of whom died on October 26 last as a result of wounds received while facing the enemy at Ganghwa (Korea). I include the certificates required to establish the pension rights of the families of these sailors. Two of these brave fellows, Grosselin and Pallier, leave behind young children; the other was the mainstay of his elderly parents. I take the liberty of commending them to your care, hoping that you will grant them some help taken from the invalids’ fund while waiting for the pension application to be completed.”

Ambushed at the temple

After this, while the Koreans bring in more troops and watch the French, nothing much happens. The French burn some more minor fortification, and sail to and fro for no clear purpose. Finally, it is November 9. Time for a picnic at Cheondeung-sa temple, surrounded by a ring of fortifications! The most vivid description is that by Henri Zuber: “On November 8 in the evening, we received a report that 300 Korean soldiers had come from the mainland and were entrenched in a strong position five miles to the south of Ganghwa. It was decided that a column would go the next day to attack this enemy. The landing company from the Primauguet and a division of the third column were designated and made their preparations accordingly. Under the command of M. de Lassalle, lieutenant, I had to accompany the expedition as an artillery officer, the artillery not being used that day. We set off, numbering 150 men with little ammunition. On the 9th at noon we found ourselves in front of the designated area. We could see no one behind the walls and the gates were open; so we might have thought there was a complete absence of enemies if the case of October 26 had not been there to make us suspect a trick. The position is a hill whose average height is 400 meters, topped by four peaks connected by crenelated walls about three meters high. With even a little defense, this position, which is a veritable fortress, would be impregnable for as small a force as ours, especially without artillery. Once the pack animals were concealed in a hut, Mr. Lassalle and I were sent with one section to attack a bastion located on one of the peaks, while the rest of the column entered a sloping ravine facing the gate. So I walked with Mr. Lassalle, followed at some distance by our section. We were walking in silence.

Thirty paces from the bastion one of our men shouted to us: “Beware Gentlemen, you are being aimed at.” We raised our heads and saw twenty guns leveled at us. We barely had time to take cover before shots rang out and bullets whistled around us. At the same time, the walls were suddenly covered with people and a terrible burst of shooting surrounded them with a belt of white smoke. We beat a hasty retreat and returned down the hill under a hail of bullets and shot that produced in the air a far from harmonious whistling sound and sent earth flying around us. My poor chief received four injuries, including two very serious ones; as for me, not even my clothes were touched. After rejoining my section, I ordered them to fight back but it was a waste of cartridges and meant unnecessarily exposing ourselves, for what could we do against an enemy ten times more numerous and protected by thick walls? I soon understood that and I continued to retreat, protecting the animals that I had summoned, and joined the main column which, having advanced to within 50 paces from the gate without seeing anyone, had suddenly been horribly strafed and were retreating like us, withdrawing slowly and answering fire with fire.

“When the Koreans saw our retreat clearly underway, they climbed onto the parapets and gave a loud shout of triumph. Tears came to my eyes in rage. And without thinking I looked angrily at those 1,500 enemies, so proud of their victory. Yet they had done their duty, and why blame them?” The expedition’s doctor, E-J. Cheval, was also present and wrote: “thirty-six men were hit by the bullets of the enemy, no one was injured fatally, almost all the injuries were minor; among the thirty-six wounded, there were five officers, all ensigns..... Most of these injuries were to the limbs, especially the lower limbs, which were pierced in a transverse direction. Indeed, the enemy had fired from an elevated point and had made their shots converge towards the bottom of the valley, where our men offered their flank.”

There is a considerable difference between this description and that received by the Council the next day: “This very day, around noon, the general of the pirates, mounted on a horse and leading several hundred soldiers, arrived; he divided his forces to approach the east gate and the south gate. Our soldiers then fired a volley of rifle shots, some hitting the mark, others not; the enemies also fired from afar, reaching the interior of the ramparts; the steward of the Seondu fort and a man from the town, Tcha Tjai-tjyoun, were hit and fell; a captain also shot was killed. As for these pirate individuals, we killed some: they picked up the corpses and took them away. But they have a reserve of strength, while we have no means of advancing; moreover, powder and bullets, everything is exhausted: have we ever seen such distress? Eventually these pirate individuals retreated, saying they will seek reinforcements to return again. Our soldiers lack the tools to make anything, which is why I am hastily sending you this report. Send us bullets and powder immediately; also send every last hunter from Pyongyang and Hwanghae-do to save this isolated fortress. As for the special hunters from the capital camp with powder and bullets, and also the hunters who are in the army, send them successively to help us....”

A little later the vanguard colonel Yi Yong-heui said that he received from the commander of the Jeongjeok-san fortress, Yang Heon-su the following report: “In the victory bulletin that I have just sent, coming out of a great fight and overwhelmed with a hundred worries, I could not give details. This fortress is such a position that it had to be guarded; also, from the 1st of this moon, these individuals, numbering 60 and more, entered the fortress and, after observing everything from the four sides, they broke the utensils of the monks and left. Now, that very night, our soldiers landed in secret and came to us, and the enemies knew nothing about it. So today they came, as if to observe more thoroughly how the fortress was guarded. The chief was on horseback; they led mules loaded with baggage, wine and provisions, and they were without mistrust; when they divided to enter through the South Gate, our soldiers arrayed on the right and left in ambush, all fired together; the enemy had 6 killed, and we had one; In addition, the steward of the Seondu fort was shot. But the pirates did not dare to invade the fortress, they left a lot of luggage and utensils there and left. Our soldiers collected them and I ordered the monks to keep them in order to take an inventory of them later and draw up a report.

“But our soldiers, who have just had this harsh alert and whose powder and bullet ammunition are exhausted, have only one voice to ask for reinforcement; because if tomorrow the enemy returns with reinforced numbers, we cannot know to what extremity we will be reduced. Let hunters numbering 300 be sent to us tomorrow before daylight to lend us a hand.” The next day he sends an even more amazing report: “In yesterday's battle 6 enemies were killed outside the South Gate: our soldiers saw them clearly with their eyes; this is why in my report I noted only 6 killed. But, during the night of yesterday, four or five inhabitants of the villages came to bring news to our camp, saying: When the defeated enemies retreated, we observed them well halfway along the road; they went on foot and, for the dead, there were more than 40 corpses in a line; they had surrounded them all and loaded a certain number of packs with them to return home; for their part, the number of deaths easily rises to more than 50.”

A sudden withdrawal

Fr. Ridel, who had been present at the incident, was horrified by what followed the next day, November 10: “In the evening, an expedition to repair this failure, destroy the pagoda and avenge the honor of the tricolor flag if compromised was, it is said, decided, and everyone believed it. What amazement, what astonishment the next day, when we learned that the admiral had given the order to d’Osery's division to make preparations for departure, to burn everything in the town of Ganghwa; to abandon the place, to return to the ships; we were dismayed, the flight was beginning, we were defeated; France routed by Korea!... During the day, then, the detachment from the town of Ganghwa arrived; in the evening embarkation began, which continued throughout the night, and the next day, at 6 o'clock, the ships and the entire expedition were on their way, or rather in retreat. – We thus left all the fortification work that we had done to defend ourselves, and which was not yet completed, the improvements that we had made to the houses to provide more comfortable accommodation and guarantee security in the cold, a newly built oven which had only been used once or twice, and which remained with all this work, to prove that the intention in building it had been to stay longer. We also left a large number of various objects that we had brought from the city and that we had not been able to take on board, the admiral at the last moment having given the order to take only what was part of the equipment, so as not to overload the ships which were to transport the troops...

“We left on the road to Ganghwa, halfway from the town to the shore, the big bell which we had wanted to take away and which now, because of the haste of departure we were obliged to leave halfway; wouldn't the Koreans take it back, carry it in triumph as a trophy and as proof of their victory, and of the flight of the French. All the troops paraded in front of this bell which blocked the road; we would have liked to take it away, one or two days would have been enough to put it on board; but after the failure we had just suffered, we were in a hurry to leave; we therefore had to resign ourselves to the shame of leaving this evidence of a hasty flight there. Later, however, the audience will be told that it was the ice that forced us to leave Ganghwa. As soon as the last marines had all left, residents who had observed and understood the movement returned to their homes, amazed at the metamorphosis that some of them had been subjected to.”

On 5.10 (November 11) the Council was taken by surprise on receiving several reports saying that all the French ships had sailed away from Gapgot heading south, away from Ganghwa and it quite soon became clear that the expedition was over.

Kill them all

The result of Admiral Roze’s pointless expedition was as Fr. Ridel had feared. The persecution was intensified. On 10.10 the Council is informed of the execution of 4 Christians (November 16) at Yanghwajin. On 14.10 (November 20) it hears that 3 more Christians have been executed at Yanghwajin followed by 2 others ten days later. They were not the first, 3 others had been executed there on 16.09 (October 24) and the choice of this place for their execution was directly linked to the fact that the French had landed there during their initial survey. There was a desire to wash away this foreign defilement with the blood of unrepentant Christians. Others would follow.

On 15.10 already orders were given: “For foreign ships to have crossed many seas to come and attack and plunder us, there must necessarily have been bad subjects from our kingdom who came with them or who colluded. Therefore the most urgent measure, to be taken above all, is to punish the supporters of the perverse doctrine and to annihilate them to the last one. This is why, in the capital, the two administrations of the Ministry of Crimes and the Seoul Prefecture, outside the 8 provinces and the 4 fortresses, as well as the various criminal courts, will have to arrest all the supporters of the evil doctrine and, at the end of each month, they will report it to our government. If a man makes 20 arrests or more, let him be appointed military mandarin of a good border post, whose holder will be moved and sent there. But if, to complete this number, he makes false denunciations, so that the true and the false are mixed, or that, out of grudge or private hatred, he falsely arrests peaceful people, it will be necessary to apply to this satellite the rule of reversion of punishment. As for the dignitaries of these administrations, the governors, military and maritime prefects, and the criminal judges who will not do their duty, let them be punished according to the full rigor of the laws.”

Final confirmation that the French had sailed away was only received the following day. On 18.10 (November 24) the Regent proposed a new measure designed to protect the country from the western powers by making all imports of foreign goods illegal: “Order stating that if, during the customs inspection, any European object is discovered, from Uiju itself we first proceed to the decapitation of the culprit and then make a report. All the troubles that European barbarians have caused us in the past and today have, in short, these commercial relations as a pretext, because of the European objects that are used in our kingdom. This is why it was proposed to us and we decreed to prohibit them absolutely. When were the orders relating to this prohibition not urgent and essential? But the current situation is such that it is important to guard ourselves more strictly than ever. We don't know if the magistrate in charge of the border will be able to stand up to it or not. At the customs inspection of the three rivers, if any culprit is discovered, let him be beheaded first in the city of Uiju itself, and only then report it.” A few days later the same measures were taken to prevent any imports through Japan coming in through Busan.

The aftermath

Meanwhile, Fr. Féron had joined Fr. Calais in hiding and writing much later (November 29), from China, he says how, late in September, Fr. Calais heard that Admiral Roze had come to the Korean coast. They therefore set off in a small boat, hoping to meet the ships but were told that they had already left. They finally decided to try to sail to China and set off around October 11-12, hugging the coast as much as possible. When they reached Chefoo on October 26 they met a British friend of earlier missionaries and learned that the French military expedition was well underway, with Fr. Ridel helping, and that the Laplace was expected to arrive from Korea on November 5. They then went back to Korea when that ship returned, hoping to be able to rejoin their mission, but they only arrived on November 16, just as the French were withdrawing, and by November 26 they were back in Chefoo on the Primauguet with no hope of returning to Korea as missionaries for the present, at least.

Fr. Féron served as interpreter and guide to Ernst Oppert’s ill-fated 1868 visit, which provoked a much fiercer persecution of Christians. In 1900 he returned briefly to Korea, where Christianity, both Protestant and Catholic, was now practised openly, in order to testify before Bishop Mutel as part of the beatification of the Korean martyrs. He was by then a missionary in India, where he died in 1903. Fr. Calais went to Manchuria in 1867, and tried to cross back in Korea but failed. In 1870 he became a Trappist monk and died in 1884.

Fr. Ridel, alone returned to Korea, having been consecrated Apostolic Vicar in Rome in 1870. In September 1877 he entered Korea from Manchuria and spent several months in hiding before he was arrested at the end of January 1878 and after spending time in prison, he was expelled toward China on June 5, after diplomatic efforts by France, China and Japan. After suffering a stroke in Japan in 1882 he returned to France where he died June 20 1884.

In 1876, ten years after the events of 1866, Fr. Blanc entered Korea with Fr. Deguette, who was soon expelled, then returned in 1883 and served until his death in 1890. Fr. Blanc avoided arrest and in 1877 was given the title of coadjutor bishop to Bishop Ridel although he was only able to travel to Japan to be consecrated in 1883. On Bishop Ridel’s death, Bishop Blanc became the Apostolic Vicar. A few years later, when freedom of religion was obtained, he brought French sisters in to care for orphans and purchased the land where later Myeongdong Cathedral and the Bishop’s residence was built. He died in Seoul in 1890.

Fr. Gustave Mutel first arrived in Korea in 1880 but in 1885 was called back to Paris to teach in the seminary of the Foreign Missions Society. In August 1890, after the death of Bishop Blanc, he was appointed Apostolic Vicar and arrived in Seoul early in 1891. He the served as Bishop until January 1933. He worked hard for the beatification of the Korean martyrs, of whom 75 were beatified in Rome in 1925, thanks largely to his efforts.